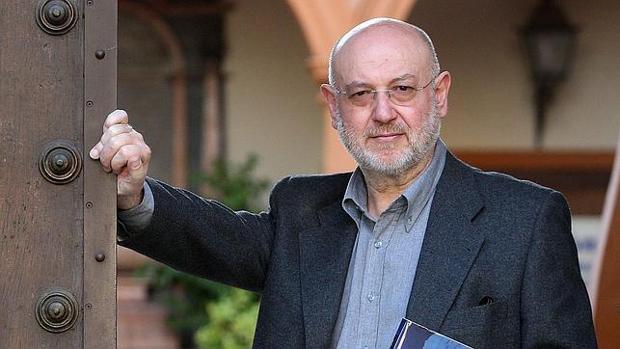

The Return of the Magician: A Conversation with Sergio Pitol

El retorno del mago

Pedro M. Domene

Translated to English by Angela McEwan

Sergio Pitol recently published El mago de Viena (The Magician of Vienna) and Los mejores cuentos (The Best Stories) in Spain. The latter book has a prologue written by Enrique Vila Matas of Barcelona. Both titles confirm the position of the author of Domar a la divina Garza (Taming the Divine Heron) as one of the great voices in contemporary Spanish narrative.

In the following conversation, the writer confesses his doubts in this way: “It’s possible that my novelistic ability has dried up.” Nevertheless, with the appearance this year of those two titles it becomes obvious that the productive link between life and work—so explored by Pitol— continues to nourish the wakefulness, the dreams and the insomnia of his vivid creative imagination, which now has received the most prestigious recognition which our language can bestow on its authors: the 2005 Cervantes Prize.

Sergio Pitol is the author of Tiempo cercado (Corraled Time) (1959), Infierno de todos (Inferno for All) (1965),Los climas (The Climates) (1966), No hay tal lugar (There is no Such Place) (1967), Del encuentro nupcial (About the Nuptial Encounter) (1970); the novels: El tañido de una flauta (The Sound of a Flute) (1972), Juegos florales (Flower Games) (1982), El desfile del amor (The Parade of Love) (1984), and the essay collections: El arte de la fuga (The Art of Escape) (1996), Soñar la realidad (Dreaming Reality) (1998), Pasión por la trama (Passion for the Plot) (1999), El viaje (The Trip) (2001). In 1999 he was awarded the Juan Rulfo Prize for the whole of his literary achievement.

* * *

Sergio Pitol: El desfile del amor, and the immediate publication of the novel in Barcelona meant not only to set foot in Spain, but also to be recognized in Mexico. Shortly after the appearance of my first book of stories, in an almost secret edition, I left Mexico, and for almost thirty years I lived outside my country. I visited it sometimes, on two occasions I spent long periods, like a year, but knowing from the beginning that I was going to leave. Here in Mexico I had a few excellent friends; my books came out without my being present, and carried on a phantom life. Outside of a handful of very faithful readers and enthusiasts, for the rest of the Mexican readers I was non-existent, a shadow, an eccentric, far from the reality of Mexico and Hispano-America, cooped up in a moveable marble tower, creating audacious stories set in Venice or Samarkand. I must say that I’m not complaining; that reputation was rather fun. To suddenly arrive in Mexico to spend a few weeks and be wined and dined by very close old friends was wonderful, as well as finding a small group of young people in the most unexpected corner of the city that knew my work better than I did. After this novel a wider public became aware of me.

Pedro M. Domene: Your twisted universe is even more accentuated in Domar a la divina garza. Is your world really like that?

S.P.: Domar a la divina garza. What a story! I wrote it traveling between Madeira, Lanzarote, and Marienbad, in marvelous clinics where I was convalescing from a complicated gall bladder operation. It was a life of spas, boring, crepuscular, and gluttonous, like a Von Stroheim film. It was a period devoted to Gogol. I read and re-read almost his entire work, as well as several excellent books on his writing and bizarre life. At that time I read Bakhtin’s book on Rabelais, but more than anything I read about popular culture at the end of the Middle Ages and beginning of the Renaissance. Those readings, which were a hymn to liberty, and those of Gogol, became an integral part of my theme. El desfile del amor, the previous one, the prizewinning one, is a tragicomic, impudent parody, and Domar a la divina garza radicalizes all that, it converts it into something disgusting with unpleasant aromas.

At present I’m writing a little book about a trip to Georgia in 1985, in which I narrate a personal experience about the excremental slant I introduced in the novel. It was the last novel I wrote in Europe. I was in Barcelona for the presentation. Jorge Herralde went all out on that occasion, and every day in my hotel I received many journalists from the cultural sections of the Madrid and Catalan press. Some friends who had already read it praised it highly. I really felt like the divine heron. Days later, in Madrid I boarded the plane that would take me to Mexico, and the first thing I did, like everyone else, was to pick up some newspapers and magazines to glance through during the trip. I opened the first, which no longer exists, looked for the cultural section and immediately saw the brilliant cover of my book; and I began to read the commentary. The horrors being said about me and my novel, the savagery with which I was attacked, I don’t remember having ever seen, either against me or against any other author. The commentator stated that he had thrown my literary trajectory in the urinal, that I had been seduced by the money that an author collects from books as repellent as that one.

That once I had tumbled into the sewer it would be very difficult for me to get out of it. I told myself that it wasn’t possible that such a thing could happen, that I could be insulted with such violence, and I concluded that none of it was real, that I was dreaming, sunk in the middle of a nightmare. This soothed me and I was able to sleep for a while. When I woke up I again read that tirade and found that yes, it was true, it was real, but now the shock had passed. I had been carried away in Barcelona, and followed Bakhtin’s outline of the carnival: coronation, celebration and final beating. It was an exemplary lesson. The only thing that bothered me was that it would be the first review of my novel, and might be the first one to arrive in Mexico.

Shortly thereafter when I received the reviews of Masoliver Ródenas and of Mercedes Monmany I calmed down. Both started their articles with the affirmation thatDomar a la divina garza was a masterwork.

P .M. D.: La vida conyugal ends that triptych for the moment and presupposes your displeasure with the present world.

S. P.: La vida conyugal is the chronicle of fifty years of married life. There is a constantly warring couple with the backdrop of a society that has lost its energy, vitality and sense of almost everything. A world that is like a rudderless ship heading for disaster. A society resulting from many decades of corruption and decay, the flower of the PRI (Revolutionary Institutional Party). I feel tenderness for the protagonist, for his capacity to survive, for his chaotic rebelliousness, for his limitations, for all his fruitless efforts. At the end the couple celebrates their fifty years of marriage, their golden wedding anniversary, and what is left of it is rubble, mutilated bodies and an angry old age. The desire of each to break off with the other as soon as possible. That is what their fifty years of marriage has been; there is no cure for the couple, they will go on that way till the end.

P. M. D.: On your definitive return to Mexico in 1988, your fame as a writer has been growing and now, in a manner of speaking, you are in a process of more reflective writing. Is El arte de la fuga the synthesis of this period or perhaps of a whole lifetime? Does this book represent a kind of sentimental education and a civil education to show that ego and its exterior manifestation?

S. P.: In Mexico everyone says it’s my best book. Personally I think that if anything that I’ve written survives me it will be some paragraphs of Vals de Mefisto. More than that I find impossible. El arte de la fuga contains, if not the most perfect, the most intense and most entertaining of my work. Writing some of its chapters caused me intolerable pain, others entertained me and made me feel very happy. There are essays that turn into stories and then go back to being essays. There is trivia, winks, gossip, dreams galore, digressions about Thomas Mann, but also about my dog, Sacho. It ends with an account of my trip to the state of Chiapas a few weeks before the insurrection. I think, as I already told you, that everything I write is a kind of infused biography, oblique, and in this book the flow of life erupted more forcefully and therefore is more visible than in any of my other books.

P. M. D.: In some way does El arte de la fuga, in a country that is facing groups of differing opinions, become a kind of commitment for the independence and tolerance of the intellectual? Perhaps because of that kind of “introspective period” of which Carlos Monsivàis has spoken you have again published a book of markedly thoughtful character such as Pasión por la trama.

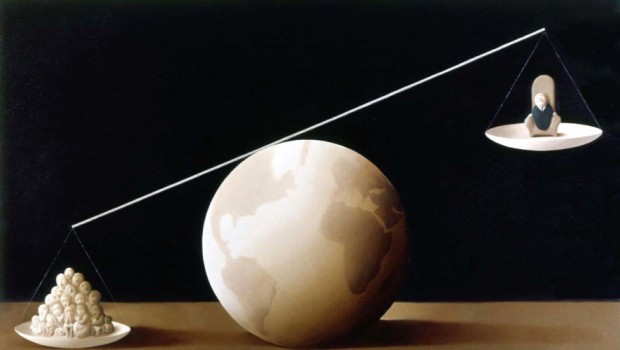

S. P.: You see, for the groups of Mexican literati none of them would have a problem digesting my comments on writing, reading and travel, which are the mainstays of that book. They might, of course, disagree, or perhaps one of those rigid theorists, aligned to a “scientific” current of literature might have considered my digressions on writing unnecessary, and even tossed the book in the trashcan because of finding the writing inane. But the real resistance to El arte de la fuga, although they were few, came from some organic intellectuals, those who submit themselves voluntarily to the Prince, they adore him and always receive the benefits. But at my age I have come to enjoy the possibility of having enemies. When one fights with the family or with dear friends, it is always a wound, whether one is to blame or is the victim of the event that caused the rupture. On the other hand, to be hated by someone you don’t care about, someone you despise or feel indifferent toward is like winning a prize, not a big one, of course, but third or fourth place.

P .M. D.: After reading these last texts, there are two aspects which, in some way, mark a constant in your writing: friends and travel. To what degree are both aspects important in your work although the travel for you, nevertheless, does not have the sense of exploration or sightseeing, your cities are places you have experienced which appear time and again in your writing?

S. P.: I have wonderful friends with whom I disagree about almost everything, but every time I see them it gives me great pleasure, because they remind me of certain fundamental episodes in our lives, our development, or with whom I can converse about books, travels, dogs, theatre, films of the thirties and forties, preferably those of Lubitsch and Rene Clair. The friends and the cities complement each other. My curiosity about places, both known and unknown, is never satisfied. Nevertheless, I have never been able to intelligently describe a city, not even the ones I love the most. In my novels I restrict myself to certain parts of the urban map, a plaza, a street, the facade of a church, and I make use of them as a mere backdrop, perhaps like those used by the dramatists of the Golden Age of Spain or the Elizabethans in England, mere painted cloths that indicate simply that: a street, the atrium of a church, a plaza, a garden, the drawing room of a house, a room at an inn. I try to imprint a certain reality, not by the description of the places, but rather by other details of atmosphere, which also support the structure. Recently I read a book by Félix de Azúa: La invención de Caín (The Invention of Cain), which I found fascinating and which caused me to be totally envious, because I know I could never achieve anything that would equal it when I have to mention a trip in some passage.

P. M. D.: Is El viaje based on a particular immersion in the infernos of the Slavic soul?

S. P.: Not totally. El viaje tends to be a memory of my personal relationship with the Russian culture. Its primary essence is a literary construction which seems to me to be different from the kind of books on the Communist world. I try to be a camera which photographs my emotions. I’m sick of the Soviet specialists, the political specialists, who generally situate themselves in an inflexible position of absolute rejection of the world of evil.

Of course there are exceptions, among them two eminent Poles: K.S. Karol and Ryszard Kapuseynski. In addition to Soviet politics, they were interested in the society, especially Russian individuality, its eccentricity, the impossibility of fitting everyone into the same mold; and in addition to other methods of following the temper of their culture, they observed the literature, music, films and theater. Of course, what they call the Russian soul, which is very complex, is only an imitation, a parody, a temperamental explosion. Cioran wrote prodigiously about the religious feelings of the Russians, their elevated sensibility. Cioran insinuated that the “Russian soul” was not similar to that of other populations, but rather was superior. Now, the grossness, the vulgarity, the cruelty can be extreme. You can read any work of Dostoyevski to prove it: Prince Mirsky, the merchant Rogadov.

P. M. D.: Perhaps one has to see in this book one step more in the process of making literature more literary? I say that because this little diary expresses great homage to Russian literature. Is that it?

S. P.: Yes, perhaps I tried to make it different from El arte de la fuga, which is a grandfather of El viaje. This one is less powerful than its predecessor. But that was my intention. In El arte de la fuga the movement is constant and moved by the leverage of pathos. In El viaje I restrict the pathetic possibilities. Actually, the only time it appears is in the terrible letter of Meyerhold, the great man of the theater, when he describes to a high-ranking politician the tortures inflicted upon him by the KGB. In this book, the main basis of the work is a real diary, mine, and those pages of the diary bring forth other moments: previous stays in Moscow on a diplomatic assignment, readings of Russian authors since childhood, painting, friendships, the Russian avant-garde of the early years of the revolution, dreams, games which disguise reality, parody, quotations to back up my stories, especially of two geniuses born in the Balkans who later became universally famous: Canetti and Cioran. In the background of everything, behind the words, flows a literary current, a desire to construct a great edifice in homage to Russian literature.

P. M. D.: Dreams are present, again, in this work. Is this how you justify a large part of your creative process?

S. P.: Dreams are absolutely necessary in writing, they appeared in my first stories from almost fifty years ago and they never tire me. They appear in other forms. They are almost the most brilliant and powerful part of a book. Dreams can be part of my work, but only if they form an active part of the architecture and theme of a book. Their heritage in literature is enormous. In Dostoyevski the dream element is indispensable. That dream of Raskolnikov very near the beginning where a little boy watches in terror as a crowd beats a poor old horse to death, and passersby stop to watch that carnage as if it were something normal and almost pleasant. In The Magic Mountain there is Hans Castorp’s masterful dream which gives the novel its sense of profundity. In Borges there are magnificent dreams. The dream is one of the pillars of the baroque: the dreams of Quevedo, the theater of Calderón, the poetry of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, etc. In all modesty, I align myself with that family.

P. M. D.: So, is this the path you are taking to continue trying out literature? I mean, the art of playing with the genres to compose a tale halfway between what one presupposes is a novel, a chronicle or an autobiography?

S. P.: In a surprising way for me, and not previously thought out, I began to feel that I was distancing myself from my latest novels, the ones from the carnival cycle. It seemed to me that to start another one would become mechanical, and I saw that each time I wrote an essay or a conference, some minimal narrative threads appeared in the text, and even some eccentric characters, which broke the flow of the essay. Or also, I would appear as a character to tell some rather private story. The moment arrived that I intensified those happenstances, I strengthened them so that they became fundamental parts of the structure and that is how El arte de la fugawas born, which was more far-reaching than all my previous books. It mixes various genres, the author, me, is the protagonist of some texts, then appears as a mere amanuensis. It is a novel, a life chronicle, nourished by frivolities, but also by passions. Two other titles spun off from this book: Pasión por la trama and El viaje. Now I think it’s time to end this. I’m afraid that if I follow with another book in the same style, I would be repeating myself, or rather, I would be repeating the same literary procedure I used. I feel as if I am in a no-man’s land. Soon I’ll be going to Spain, to a town on the Costa Brava, to shut myself up alone for two months to clear my mind and try to figure out what I am going to write.

P. M. D.: An obligatory question: What project are you working on now if you have awakened from that long dream implied by your latest books?

S. P.: I have some themes, I need to ponder them. It’s possible that my novelistic ability has dried up. Next year I’ll be seventy years old. To help me accept the fact, I tell myself that two of the novelists I have admired, E.M. Forster y Julien Graq, who produced marvelous novels, stopped doing them before they were fifty, without giving up writing. We’ll see what happens!

Sergio Pitol publicó recientemente en España El mago de Viena y Los mejores cuentos, con prólogo este último del barcelonés Enrique Vila Matas. Ambos títulos confirman el lugar que el autor de Domar a la divina garza ocupa como una de las voces mayores de la narrativa en español contemporánea.

En la siguiente conversación el escritor confiesa así sus dudas: “es posible que mi capacidad novelística se haya agotado”. Sin embargo, con la aparición este año de aquellos dos títulos resulta obvio que el fértil vínculo entre vida y obra —tan explorado por Pitol— continúa alimentando las vigilias, los sueños e insomnios de esta fuerte imaginación creadora, merecedora hoy del reconocimiento más importante que nuestra lengua otorga a sus autores: el Premio Cervantes 2005.

Sergio Pitol es autor de Tiempo cercado (1959), Infierno de todos (1965), Los climas (1966), No hay tal lugar(1967), Del encuentro nupcial (1970); las novelas: El tañido de una flauta (1972), Juegos florales (1982), El desfile del amor (1984), y de los libros de ensayos, El arte de la fuga (1996), Soñar la realidad (1998), Pasión por la trama (1999), El viaje (2001). En 1999 obtuvo en México el Premio Juan Rulfo al conjunto de su labor literaria.

* * *

Sergio Pitol: El desfile del amor, y la inmediata publicación de la novela en Barcelona significaron no sólo poner un pie en España, sino ser reconocido también en México. Poco después de la aparición de mi primer libro de cuentos, en una edición casi secreta, salí de México, y durante cerca de treinta años viví fuera de mi país. Lo visitaba algunas veces, en dos ocasiones pasé temporadas largas, como de un año, pero con la seguridad desde el principio de que iba a partir. Tenía aquí en México pocos pero excelentes amigos; mis libros aparecieron sin estar yo presente, y arrastraban una vida fantasmal. Fuera de un puñado de lectores fidelísimos y entusiastas, para el resto de los lectores mexicanos era yo inexistente, una sombra, un excéntrico, alejado de la realidad mexicana y también de la hispanoamericana, enclaustrado en una móvil torre de marfil, fraguando historias bizarras que tenían lugar en Venecia o Samarcanda. Debo decir que no me quejo; tenía bastante chiste esa reputación. Llegar a México de repente para pasar unas cuantas semanas y ser celebrado por viejos amigos muy cercanos era formidable, como también lo era encontrar en el lugar más inesperado de la ciudad a un pequeño grupo de jóvenes que conocían mejor mi obra que yo mismo. A partir de esta novela fui percibido por un público más amplio.

Pedro M. Domene: Su universo esperpéntico se acentúa aún más en Domar a la divina garza, ¿su mundo es realmente así?

S. P.: Domar a la divina garza, ¡qué historia! La escribí entre Madeira, Lanzarote y Marienbad, en clínicas maravillosas donde convalecía de una complicada operación vesicular. Vida de spa, fastidiosa, crepuscular, golosa como del cine de Von Stroheim. Fue un periodo consagrado a Gogol. Leí y releí casi la totalidad de su obra, y varios libros excelentes sobre su literatura y su estrambótica existencia. Leí entonces el libro de Bajtín sobre Rabelais, pero más que todo sobre la cultura popular a finales de la Edad Media e inicios del Renacimiento. Esa lectura, que era un canto a la libertad, y la de Gogol, fueron integrándose a mi tema. El desfile del amor, la anterior, la premiada, es una historia paródica, tragicómica, desparpajada, y Domar a la divina garza radicaliza todo eso, lo convierte en un esperpento con aromas repelentes. En estos días estoy escribiendo un librito sobre un viaje a Georgia en 1985, donde narro una experiencia personal sobre la carga excrementicia que introduje en la novela. Fue la última novela que escribí en Europa. Estuve en Barcelona para su presentación. Jorge Herralde echó la casa por la ventana en esa ocasión, y todos los días recibía en mi hotel a muchos periodistas de las secciones culturales de la prensa catalana y la de Madrid. Algunos amigos que la habían leído ya fueron muy elogiosos. Me sentía, en verdad, la divina garza. Días después, subí en Madrid al avión que me conduciría a México, y lo primero que hice, como todos, fue recoger algunos periódicos y revistas para hojearlas durante el viaje. Abrí la primera, ya desaparecida, busqué la sección cultural y vi de inmediato la brillante portada de mi libro; y comencé a leer el comentario. Los horrores que se decían de mí y de mi novela, la saña con que me daban una paliza monumental no recuerdo haberla visto nunca, no sobre mí sino sobre ningún otro autor. El comentarista declaraba que había lanzado al mingitorio mi trayectoria literaria, que había sido seducido por el oro que un autor recauda con libros tan repelentes como aquél. Que ya una vez despeñado en la cloaca me sería muy difícil salir de ella. Me decía que no era posible que eso ocurriera, que me insultaran con tanta violencia, y deduje que nada era verdad, que estaba yo soñando, sumido en medio de una pesadilla, lo cual me tranquilizó y me permitió dormir por un buen rato. Al despertar volví a leer aquella arenga y comprobé que sí, que era cierto, que era la plena realidad, pero ya el shock había pasado. Me había animado demasiado en Barcelona, y seguía el esquema de Bajtín sobre el carnaval: coronación, fiesta y paliza final. Fue una lección ejemplar. Lo único que me molestaba es que esa fuera la primera nota bibliográfica que recibía mi novela, y posiblemente la primera que llegaría a México. Cuando poco después me llegaron las notas de Masoliver Ródenas y de Mercedes Monmany me tranquilicé. Ambos iniciaban sus artículos con la aseveración de queDomar a la divina garza era una obra maestra.

P. M. D.: La vida conyugal cierra por el momento ese tríptico y presupone su desagrado con el mundo actual.

S. P.: La vida conyugal es la crónica de cincuenta años de vida marital. Hay una pareja permanentemente en guerra con el fondo de una sociedad que ha perdido la energía, la vitalidad y el sentido de casi todas las cosas. Un mundo que es como un navío ebrio que se dirige al desastre. La sociedad resultante de muchas décadas de corrupción y descomposición, la flor del PRI. Siento ternura por la protagonista, por su capacidad de sobrevivencia, por su rebeldía caótica, por sus limitaciones, por todos sus esfuerzos infructuosos. Al final la pareja celebra sus cincuenta años de casados, sus bodas de oro, y lo que queda de ella son escombros, cuerpos mutilados y una iracunda vejez. Deseos de acabar cada uno con el otro lo más pronto posible. Eso han sido sus cincuenta años de casados; no hay remedio para la pareja, seguirá así hasta el final.

P. M. D.: A su vuelta definitiva a México en 1988, su fama de escritor ha ido creciendo y ahora se encuentra en un proceso de escritura, por decirlo de alguna manera, más reflexiva. ¿El arte de la fuga es la síntesis de este periodo o quizá de toda una vida? ¿Significa este libro una especie de educación sentimental y una educación civil para mostrar ese yo y su proyección exterior?

S. P.: En México todos dicen que es mi mejor libro. Yo personalmente creo que si algo de lo escrito me sobrevive serán algunos párrafos de Vals de Mefisto. Más de eso me resulta imposible. En El arte de la fuga está, si no lo más perfecto, sí lo más intenso y lo más divertido de mi trabajo. Escribir algunos de sus capítulos me produjo un dolor intolerable, otros me regocijaban y me hacían sentir muy feliz. Hay ensayos que se vuelven relatos y terminan de nuevo como ensayos. Hay trivia, guiños, gossip, sueños a granel, digresiones sobre Thomas Mann, pero también sobre mi perro Sacho. Termina con la crónica de un viaje al estado de Chiapas pocas semanas después de la insurrección. Creo, te lo he dicho ya, que todo lo que escribo es una forma de biografía infusa, oblicua, y en ese libro un flujo de vida irrumpió con más fuerza y desde luego se hace más visible que en cualquier otro de mis libros.

P. M. D.: ¿De alguna manera El arte de la fuga, en un país que enfrenta a distintos grupos de opinión, viene a ser como una especie de compromiso por la independencia y la tolerancia del intelectual? Quizá por esa especie de “período introspectivo” del que habla Carlos Monsiváis ha vuelto a publicar un libro de marcado carácter reflexivo como Pasión por la trama.

S. P.: Mira, a ninguno de los grupos de literatti mexicanos les podía resultar indigerible lo que anotaba yo sobre la escritura, la lectura y los viajes, que son los grandes apartados de ese libro. Podían discrepar, eso sí, o tal vez algún teórico de esos duros, alineados en una corriente “científica” de la literatura haya considerado prescindibles mis digresiones sobre la escritura, y hasta tirado el libro al bote de la basura por resultarle una escritura inane. Pero las verdaderas resistencias a El arte de la fuga, aunque fueron pocas, surgieron de parte de algunos intelectuales orgánicos, esos que se someten voluntariamente al Príncipe, lo adulan y salen siempre beneficiados. Pero a mi edad he venido a disfrutar la posibilidad de tener enemigos. Cuando uno pelea con la familia o con amigos entrañables, siempre es una herida, sea uno culpable o víctima del hecho que decidió la ruptura. En cambio, ser odiado por alguien no estimado, alguien por quien uno siente desprecio o indiferencia es como ganarse un premio, no uno grande, claro, sino de tercera o cuarta clase.

P. M. D.: Tras la lectura de estos últimos textos, hay dos aspectos que, de alguna manera, marcan una huella decisiva en su escritura: los amigos y los viajes. ¿En qué medida ambos aspectos son importantes para su obra aunque el viaje para usted, no obstante, no tiene ese sentido de exploración o recorrido, sus ciudades son lugares vividos que reaparecen una y otra vez en sus escritos?

S. P.: Tengo amigos magníficos con los que discrepo en casi todo, pero cada vez que los veo me da un gusto inmenso porque me hacen recordar determinados episodios fundamentales en nuestras vidas, nuestra formación, o con quienes tengo la posibilidad de conversar sobre libros, viajes, perros, teatro, cine de los años treinta y cuarenta, de Lubistch y Rene Clair de preferencia. Los amigos y las ciudades se complementan. Mi curiosidad por los lugares, los conocidos y los aún no vistos nunca se apacigua. Sin embargo, nunca he logrado describir inteligentemente una ciudad, ni siquiera las más amadas. En mis novelas me restrinjo a ciertos trozos del plano urbano, una plaza, una calle, la fachada de una iglesia, y me sirvo de ellas como un mero telón de fondo, quizás como los que utilizaron los dramaturgos del Siglo de Oro español o los Isabelinos en Inglaterra, meras telas pintadas que señalan sencillamente eso: una calle, el atrio de una iglesia, una plaza, un jardín, el salón de una casa, el cuarto de una posada. Trato de imprimir cierto verismo, pero no por la descripción de los lugares sino por otros detalles de atmósfera, que además apuntalan la estructura. Hace poco leí un libro de Félix de Azúa: La invención de Caínque me resultó fascinante y me produjo una envidia total, porque sé que jamás podría yo lograr nada que se iguale a eso cuando en algún pasaje tenga que mencionar un viaje.

P. M. D.: El viaje (2000), ¿se concreta en una inmersión particular a los infiernos del alma eslava?

S. P.: No del todo. El viaje tiende a recordar mi relación personal con lo ruso. Primordialmente es una construcción literaria que me pareciera distinta al tipo de libros sobre el mundo comunista. Trato de ser una cámara que fotografíe mis emociones. Estoy harto de los sovietólogos, de los politólogos, que por lo general se sitúan en una posición inflexible, de rechazo absoluto, el mundo del mal. Hay claro excepciones, entre ellas dos polacos eminentes: K. S. Karol y Ryszard Kapuscynski. Ellos se interesaban, además de la política soviética, de la sociedad, en especial de la individualidad rusa, de su excentricidad, de la imposibilidad de medir a todos con un rasero, y entre otros medios para seguir la temperatura de su cultura, observan la literatura, la música, el cine y el teatro. Claro, lo que llaman el alma rusa, que es complejísima, es tan sólo un remedo, una parodia, un estallido temperamental. Cioran escribió páginas prodigiosas sobre el sentimiento religioso de los rusos, su elevada sensibilidad. Cioran insinuaba que el “alma rusa” no es semejante a la de los otros pueblos, sino superior. Ahora, la grosería, la vulgaridad, la crueldad puede ser extrema. Hay que leer cualquier obra de Dostoievski para comprobarlo: el príncipe Mirsky, el comerciante Rogadov.

P. M. D.: ¿Quizá haya que ver en este libro un paso más en ese proceso de literaturizar la literatura?, se lo digo porque en este pequeño diario hay mucho de homenaje a la literatura rusa, ¿es así?

S. P.: Sí, tal vez intenté que no fuera igual a El arte de la fuga, que es un abuelo de El viaje. Éste es menos poderoso que su antecedente. Pero así me lo propuse. En El arte de la fuga el movimiento es constante y lo mueve la palanca del pathos. En El viaje restrinjo las posibilidades patéticas. De hecho, la única vez que aparece es en la terrible carta de Méyerhold, el gran hombre de teatro, cuando le describe a un alto político las torturas que le infligen en la KGB. En este libro el soporte de la obra es un diario real, el mío, y esas páginas del diario convocan otros momentos: estancias anteriores en Moscú en un cargo diplomático, lecturas de los rusos desde la niñez, pintura, amistades, la vanguardia rusa de los primeros años de la Revolución, sueños, juegos que disfrazan la realidad, la parodia, citas de apoyo a mis relatos, en especial de dos genios nacidos en los Balcanes para luego convertirse en personajes universales: Canetti y Cioran. En el fondo de todo, bajo la palabra, se desliza una corriente literaria, un anhelo de construir un gran edificio en homenaje a la literatura rusa.

P. M. D.: Lo onírico está, de nuevo, presente en esta obra, ¿justifica así buena parte de su proceso creativo?

S. P.: El sueño es imprescindible en la escritura, aparece desde mis primeros cuentos de hace casi cincuenta años y no me fatigan. Aparece de otro modo. Es casi la parte más brillante y poderosa de un libro. El sueño puede participar en mi obra, pero siempre que participe activamente en la arquitectura y el tema de un libro. Su prosapia en la literatura es enorme. En Dostoievski el elemento onírico es indispensable. Aquel sueño de Raskolnikov muy cerca del inicio donde un niño ve aterrado cómo una multitud mata a golpes a un pobre caballo viejo, y la gente que pasa por allí se detiene a ver esa carnicería como algo normal y casi grato. En La montaña mágica hay un sueño magistral de Hans Castorp que da el sentido profundo a la novela. En Borges hay sueños magníficos. El sueño es una de las columnas del barroco: Los sueños de Quevedo, el teatro de Calderón, la poesía de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, etc. Yo, modestamente, me acerco a esa familia.

P. M. D.: ¿Es este, pues, el camino emprendido por usted para seguir ensayando literatura? Me explico, ¿el arte de jugar con los géneros para componer un relato, a mitad entre lo que se presupone la novela, la crónica o la autobiografía?

S. P.: De una manera sorprendente para mí, y no previamente razonada, comencé a sentir que me distanciaba de mis últimas novelas, las del ciclo carnavalesco. Me parecía que emprender una más, se volvería mecánica, y veía que cada vez que escribía un ensayo o una conferencia se me imponían unas mínimas tramas narrativas en el texto, y aun algunos personajes excéntricos que rompían el flujo del ensayo. O también me aparecía yo como personaje para contar alguna historia más bien privada. Llegó el momento que intensifiqué esos percances, los fortalecí para que fueran piezas fundamentales de la estructura y así nació El arte de la fuga, que tuvo más resonancia que todos mis libros anteriores, mezcla varios géneros, el autor, yo, es el protagonista de algunos textos, luego se asume como mero escribano. Es una novela, una crónica de vida, se nutre de frivolidades, pero también de pasiones. De ese libro se desgajaron otros dos títulos: Pasión por la tramay El viaje.

Ahora creo que ya debo terminar con esto. Temo que si siguiera otro libro con el mismo estilo me repetiría, o más bien, repetiría los procedimientos literarios empleados. Me siento en tierra de nadie. Dentro de poco me iré a España, a un pueblo de la Costa Brava, a encerrarme dos meses en solitario para poner la mente en claro y tratar de saber qué voy a escribir.

P. M. D.: Una pregunta obligada, ¿qué proyecto tiene entre manos en estos momentos si es que ha despertado de ese largo sueño que han supuesto sus últimos libros?

S. P.: Tengo algunos temas, necesito rumiarlos. Es posible que mi capacidad novelística se haya apagado. El año próximo cumplo setenta años. Me digo para conformarme que dos de los novelistas que he admirado, E. M. Forster y Julien Gracq, que produjeron novelas portentosas, dejaron de hacerlas antes de los cincuenta años, sin dejar de escribir. ¡Ya veremos qué pasa!