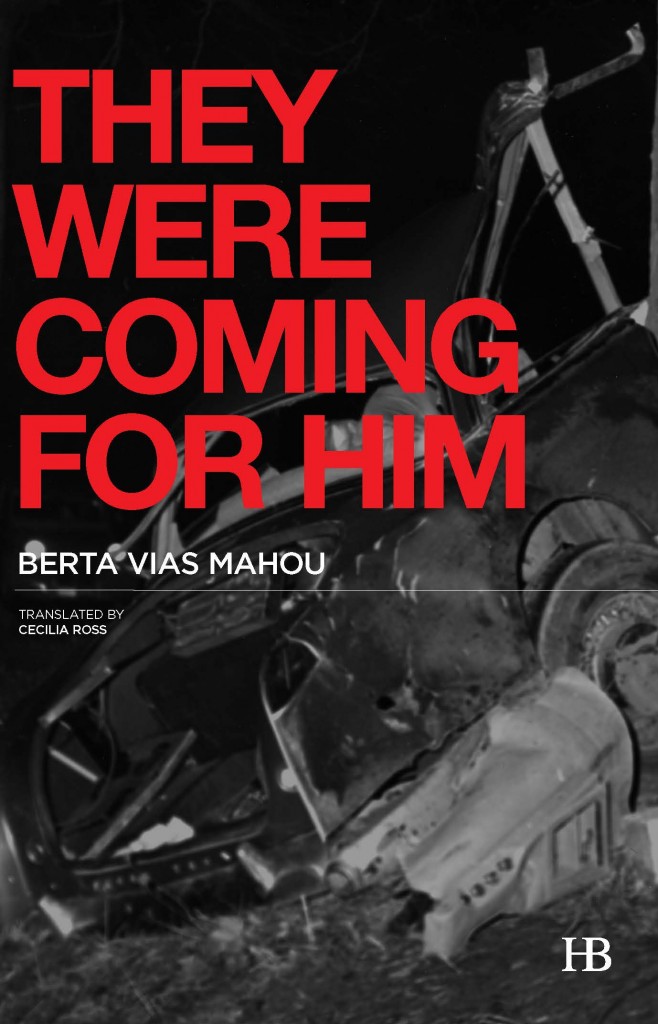

They Were Coming For Him (Fragment)

Berta Vias Mahou

Translated by Cecilia Ross

A Memory Dark With Shadow

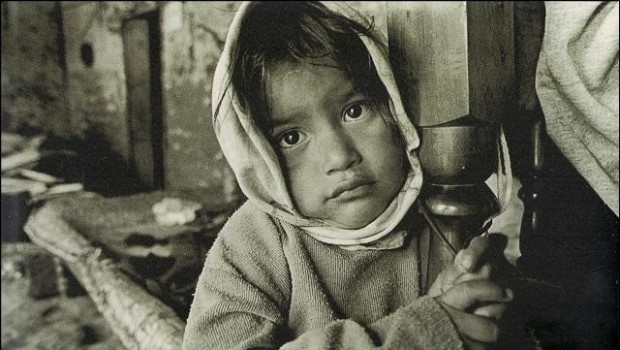

She said yes, or maybe it was no; she had to go back in time, through a memory dark with shadows, nothing was clear. The memory of the poor is less well-nourished than that of the rich, for they have fewer reference points in space, straying only rarely from their places of residence, and also fewer reference points in time, in a life that is all uniformity and grayness. They do, of course, have the memory of the heart, which is the surest, they say, but the heart grows worn with grief and toil, it forgets more rapidly under the weight of fatigue. Lost time is regained by the rich alone.

Really? Was that so? The rich didn’t seem to have much of a memory, either. Just more documentation to prop it up. Jacques set down his pen, his eyes wandered around the room, and for a few moments he gazed at the portraits of Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky, who had accompanied him for some time now. His masters. In pain and in writing, in suffering overcome. Because he was not a believer and had no religion save for the religion of freedom and the struggle for justice and the sanctity of life, they were his patron saints. He rose from his desk, a tall drafting table, took a few steps over to the window, and leaned against its frame. A horrid silence, almost otherworldly, lay over everything out there. The snow fell increasingly thickly, and in the wind those floating bits of fluff, instead of drifting calmly, slowly downward, flew crosswise at one another beyond the glass, in a conniption. The rooftops all around him were already covered with a substantial blanket of it, and the entire world seemed to have come to a standstill.

They were orange, or red, in Spain. In Algeria they were whitewashed. Rooftop terraces where laundry was hung. In the summer the sun there would scorch the parched homes. The only way to live was in the shade of closed blinds, in a half-light filled with suspended particles each brighter and more colorful than the last. In Paris, though, the rooftops were black, or a gray color just as somber as the winter skies that covered the city for much of the year. Inaccessible, unresponsive. Their slate tiles had been damp at dawn and now were white. Shrouded in that light, the birds looked even darker. They shot past and disappeared, like projectiles on the trail of some invisible target, far off in the distance. Paris is a dingy sort of town, filled with pigeons and dark courtyards, he’d written several years back. The people here have waxen skin. And when night falls, they file into their houses. In my land, at sundown, everyone rushes eagerly out. People said this was one of the most beautiful cities in the world, but for him it was wearisome, and his most ardent wish would have been to return to his own land, a man’s country, coarse, unforgettable. But that, for a combination of reasons, wasn’t possible.

If he couldn’t get himself out of there at the first opportunity, that city was going to do him in. It would crush him. And since he couldn’t go back to Algeria, Jacques dreamt of the Luberon, the Lure Mountains, Lauris, Lourmarin. Of being able to go there one day. Of the smell of basil, rosemary, and thyme, of lavender in bloom. He dreamt of a modest house, roomy and comfortable. And a landscape he could gaze out on from his windows as one gazes out on the sea from atop a cliff. Leaving Paris. A longing few shared, and many couldn’t even comprehend. Possibly only his friend René. One of the last remaining friends he had. He, for whom friendship had always held such importance. But René spent a substantial amount of time in Provence, while Jacques was still trapped in this capital city he detested. Perhaps because he was a monster, a barbarian. At least that’s how he’d always seen himself, as one who’d betrayed his kin, left them behind, in a country that was being steadily and progressively gnawed away at by the cancer of violence.

Lost time is regained by the rich alone. He himself had come to represent a prime example. But what would have become of him if it hadn’t been for the support of his high school teacher, that helping hand that had reached out to him then, expecting nothing in exchange, simply because he thought he deserved it more than others, that he would put the opportunity to better use? He would never have set about attempting to regain his lost time. Most likely, he would have done nothing more than waste it, resignedly, patiently, like so many other men and women throughout the ages and in so many different parts of the world. Like his mother. And yet it was back then that he’d known what happiness was. Poverty kept him from thinking that all was well under the sun and in history, while the sun taught him that history wasn’t everything. Back then he lived in the present. Barefooted. Practically naked. Frolicking with the other boys through the dust-filled streets and along the beach. Now, the past stretched out behind him, the future seemed to shrink in inverse proportion to it, and the present was slipping away.

There, he’d gotten by with very few things, and even those were things he didn’t possess. The sun, the sea, the wind, the stars. He recalled the nomads of Djelfa. Poor, destitute, offering every guest their all. Yes, he had grown up by the sea, far from that city he was looking at now through the window, that capital hunkered down in the interior of the world’s smallest continent, and poverty had never felt to him like a hardship. He’d never heard any complaints or clamoring around him. They saw that life as natural. Later, he’d lost it, he’d lost the sea. And the sun. From that point on, all luxuries seemed gray. Poverty, intolerable. He did not belong among that race of people now surrounding him, that race of people who were all so preoccupied with money and so bored deep down inside. Who transformed their tables at this or that Left Bank café into courtrooms and themselves into judges, unsparing with various victims and magnanimous with certain tyrants, handing down sentences on matters they knew nothing about between sips of whisky, or coffee, and flippant, supposedly freethinking remarks.

How distant, in contrast, were the sun, the sea, the simple beach life. And how unattainable was peace. He longed for the solitude of a stone column. For that of an olive tree under a summer sky. That lesson in love and patience that had been imparted to him by the desolate desert expanses. He knew he would eventually end up buying a house. And furniture. And he would become a slave, despite living the life of a rich man, a slave bent on regaining his time. Like Proust, whom he imagined tossing and turning in his bed, inside a room lined floor to ceiling with corkboard, trying to shield himself from the noise, from the entire world, in search of words, like him. Searching for nothing. Or almost nothing. A slice of immortality. He imagined someone else, too, someone who had once been a friend of his, Jean Paul, whose father had, like his own, died young. Another dead man who hadn’t had time enough to be a father, easily young enough to have been his son’s son at this point. Just one of the commonalities he and Jean Paul still shared. Like literature.

Not even his own commitment to the poor, the persecuted, and the voiceless was the same anymore, not since a few years earlier when Jean Paul, Monsieur Néant, as he now called him, had had the gall, backed by the entire team at that snazzy journal of his, to say that if the working class wanted to leave the party, they had but one way out: to kick the bucket. Always falling back on threats whenever anyone dares to deviate even the slightest from the doctrine that’s being pushed. All anti- Communists are dogs, he’d bark. That was the least he might say. And Jacques sitting there attempting to affect an air of bovine naturality and patience, but unsuccessfully, because what he really needed, what was still wanting there, was a revolution. The simultaneously urgent and gradual revolution of souls. I don’t have time to go around writing for journals, he told himself, not even if it means getting to shoot down one of Jean Paul’s arguments… I’ve only got so much of it left, and I want to put it into the new book.

Jean Paul, too, Monsieur Néant, too, in his devotion for books, had shut himself up from a young age in that imaginary world, the world of words, the words he read in books, the words he himself then wrote, the words he still had left to write. He, on the other hand, had gone a long while now without any of that, barely writing. He felt empty, tired. Though he knew a period of silence was sometimes necessary in order to then be able to write more, and perhaps even better. And now, beginning very recently, it seemed his memories were finally tugging at him, the weight of lost time, and a new book began to grow within his hands, a novel, although, as always, he was beset with doubts. No, not like always. His doubts now were even heavier. The craft of writing seemed to have nothing remotely craft-like about it. It was increasingly painful, increasingly difficult, ever more solitary. The unease, the scruples were ever greater. And ever more frequent the periods of fruitlessness, which threatened to become permanent each time they loomed into view, each time they took root, plunging him into a f it of anxiety only for their transience to eventually become plain once that mysterious fount began, finally, to f low once more.

If I had to write a book on morals, he’d quipped at an early point in his career, it would be a hundred pages long, and ninety-nine of them would be blank. And on the last one, I’d write, I know of only one duty, and that is to love. He hadn’t ever really moved beyond that position. And he’d always felt the temptation, deep down, to throw in the towel on that endless effort. Despite the recognition. Or perhaps because of it. Because of the responsibility involved, which was increasingly weighty. Because of all the fuss surrounding him and his books. Because of his feeling of shame. At what? What could a man possibly feel ashamed of? Of his insistence on speaking the truth? Of his persistent quest for happiness? To his mind, that was an obligation for all human beings. Perhaps it was also fear. Fear of hurting others, specifically those he loved the most. Because how could you lessen the untruth, and even the hatred, the injustice, that’s so often contained in words? And how could you repurpose words that are used by everyone, every day? How could he express all the love that he felt, love that pained him to the point of driving him to unbearable and ever more absolute silence?

Yes, there was no doubt in his mind, it was a path that led to silence. Nevertheless, he summoned his strength and wrenched himself away from his observatory at the window, the sight of the city greeting him daily with ever greater hostility, and he returned to his desk, to continue transcribing the words that were at long last bubbling up inside him. For the poor, time merely marks faint imprints along the road to death. Further, if one is to endure, one mustn’t remember overmuch, one must bond oneself to each passing day, hour by hour, as his mother did… Jacques raised his head from his paper again and turned his gaze inward, losing himself in memories. When his mother lived in a room, she left no trace of herself, at most a handkerchief she would often tease and twist between her fingers and sometimes let lie in her lap while she waited for time to pass, for lunchtime to arrive. Or bedtime. Or a visitor. He was convinced that when she died, the traces of her time spent on this earth wouldn’t be much more than that. A pair of shoes. A few items of clothing.

Or some newspaper page featuring a picture of her son, the younger of her two. Simple scraps of paper she felt such a swelling of pride for even now, when she couldn’t make them out and had to wait for someone else to read them to her. She would brush her fingers across their surface, pretending she was trying to smooth them down, that they had gotten wrinkled or dusty, and on occasion she would show them off to one of the neighbor women. Gratified, discrete and innocent in her admiration. In his memory he saw her sitting in a chair out on the patio, directly in front of the door to the house, warming her bones in the sun, a newspaper spread out across her legs. It looked like a bedsheet in her hands, not just because of the size of its pages, but because of the defenselessness evident in every one of her gestures, the look in her eyes, her smile, her helplessness in the face of all those letters she didn’t comprehend, although she did enjoy running a finger along them, staring at the pictures. His books were likewise a mystery to her. She couldn’t read them. Nor would she be able to read the book he was writing now, one he had decided to dedicate to her. To you who will never be able to read this book, Jacques had written on the first page. He, on the contrary, would leave an infinitude of pages behind him. Marks unlike those our shoes or our feet leave on the sand of a beach. These traces were doubtless less likely to disappear one day, even if someone might try to make them. Might take it upon himself to sweep away the vestiges of his journey through life. The things he had written. All those pages that were multiplying now before his eyes. All those pages filled with annotations, with ideas he was still intent on developing further, details he needed to research more fully, by picking the brains of his friends, his mother, and others who had lived through the same events, consulting books, rereading newspapers, pamphlets, and manifestos. They were filled with strike-throughs, too. Paths he’d ventured down, but left off shortly after.

Muslim brothers, all partisans of the FLN shall exterminate all Europeans, including children. Exceptions shall not be made. When he’d read that, his breath caught. It was a communiqué dated January 17 sanctioning a brutal strategy of indiscriminate attacks. Nothing new, really, since they’d already been killing children, in dozens of bombings in public places, and shootings in buses, and raids on farms, and torchings of churches and schools, and all without so much as batting an eye. But there was one difference. Now it was there for all to see, set down in ink and signed, right there on that handbill, and with it the door to apologies, to falling back on the rhetoric of unsought but inevitable accidents, of victim- blaming, was being definitively closed. It was a veritable declaration of all-out war. And just like that, the gears of violence ground to life once more. In April, following the assassination of two French paratroopers, the dead men’s comrades-in-arms had burst into an Arab bathhouse with guns blazing, out for blood, shooting any and everyone in their path, leaving some twenty or thirty dead and another twenty-something wounded. They unquestionably killed some of the terrorists that had gone there looking for a place to lie low while the police were after them, but the bathhouse also served at night as a shelter for a large number of homeless men. And no mercy was given to the poor. No mercy and not a single ounce of thought. Just as none was given by those colonists piling into their cars and carrying out raids in the Algerian highlands, shooting up the Arab peasants’ mechtas. Or by the military commanders when they broadened the practice of summary executions under the cover of a highly lax Fugitive Law. And there’d been a fresh massacre just a few days ago. In Melouza, 338 Muslim civilians had been massacred at the hands of other Muslims. Shooting and knifing as they went, they’d castrated and slit the throats of every single man in the village, supporters of Messali Hadj, founder of the Star of North Africa, the seed of the entire anti-imperialist movement, now condemned by his own more radical offspring.

The FLN’s propaganda machine would try to pin the bloodshed on the French army. For a long time they would remain unsuccessful, and that was no surprise. Torture and brutality were not the exclusive province of either side. Hatred feeds on hatred, in any culture. And when it reaches a certain fever pitch, it’s called nationalism. Sometimes, like now, Jacques was tempted to give the whole thing up, for good. To give up writing and simply live, and love, a titanic undertaking, to make up for all the fear and the pain, the suffering and the anguish that filled so many lives, in so many places all over the world, but the urge to write, to fight back against lies and violence, against totalitarianism and injustice, would inevitably prevail. And it was creeping over him once more.

Yes, if one is to endure, one mustn’t remember overmuch, one must bond oneself to each passing day, hour by hour, as his mother did… He, too, would become speechless in her presence, crippled, in his own way, and so he had to give up on ever learning anything from her. Even about that one incident that had made such a profound impression on him as a child and had pursued him his entire life, even in dreams. His father getting up at three in the morning to attend the execution of a famed criminal. He’d found out about it from his grandmother. Pirette was a hired hand at a farm in the Sahel, quite close to Algiers. He’d smashed in the skulls of his employers and the family’s three children with a hammer.

* * *

• This is an excerpt from the forthcoming book: They Were Coming For Him. It was originally published in Spanish by Acantilado (2010). Original title: Venían a buscarlo a él. The book will be realeased in june by Hispabooks.

• They Were Coming For Him. Winner of the Premio Dulce Chacón, overcoming finalists Enrique Vila-Matas and Mario Vargas Llosa.

• “An outstanding novel. Vias describes the process that will lead to Camus’ intelectual isolation and subsequent helplessness. Superb”.–Fernando R. Lafuente, ABC

Berta Vias Mahou (Madrid, 1961) is a Spanish author and translator. She has translated the works of renowned German-language writers such as Joseph Roth, Arthur Schnitzler, and Goethe. She has published short stories, an essay on the role of women in literature, and four novels. She is the winner of the Premio Dulce Chacón de Narrativa and the Premio Torrente Ballester de Narrativa, two prestigious Spanish literary fiction awards.

Berta Vias Mahou (Madrid, 1961) is a Spanish author and translator. She has translated the works of renowned German-language writers such as Joseph Roth, Arthur Schnitzler, and Goethe. She has published short stories, an essay on the role of women in literature, and four novels. She is the winner of the Premio Dulce Chacón de Narrativa and the Premio Torrente Ballester de Narrativa, two prestigious Spanish literary fiction awards.

Posted: May 3, 2016 at 1:55 am