Thus Bad Begins

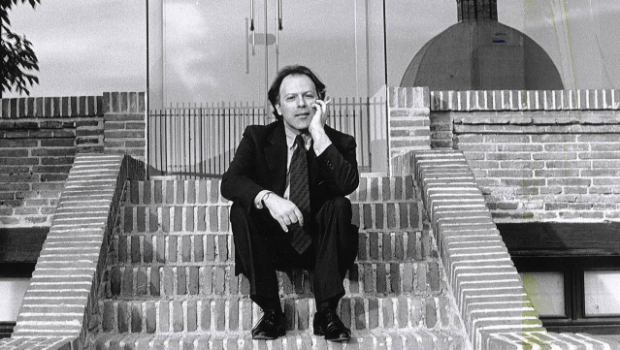

Greg Walklin

Thus Bad Begins, by Javier Marías. Translated by Margaret Jull Costa

Javier Marías doesn’t want to be “what they call a ‘real Spanish writer.'” These are authors who, Marîas says, prominently features themes and motifs of classic Spain, including bullfighting and passionate women. While these tropes are certainly absent from his novels, which tend more to involve analytic and voluble narrators dissecting the vagaries of life, Marías is still obviously fascinated with the Spanish character, and with its gestalt, and perhaps that is in no clearer form than in his latest novel, Thus Bad Begins.

The book takes place in 1980. Francisco Franco, who ruled the country for more than three and a half decades, has been dead for five years—although the caudillo still looms over everything—and the country seems to be shifting. The libertine attitude of the youth proves quite the contrast to the older generations, who had to make accommodations to survive the dictatorship. Most importantly, at least for the story of the novel, one thing hasn’t changed: the Catholic country has yet to legalize divorce.

The narrator, Juan De Vere, is a young man working as an assistant to Eduardo Muriel, a film producer, who was “one of those men of fixed habits as regards his appearance, the kind who doesn’t notice that time passes and fashions change nor that he himself is growing older…” Juan observes Muriel and his wife’s “quotidian or perfunctory aggression,” and witnesses, one night when he is staying over in their apartment, a bizarre scene: Muriel’s wife, Beatriz, begs to be let into his bedroom (they generally slept in separate rooms), and Muriel rebuffs her rather cruelly. Because of the law, they are unable to divorce, although it is obvious Muriel despises his wife—and that she is still miserably in love with him.

De Vere wonders: What could have been motivating such feelings toward each other? Being attracted to Beatriz, De Vere is especially puzzled and covetous; he ruminates extensively on her figure, displaying his own jejune obsession. When Muriel stonewalls his inquires, he begins to investigate Beatriz on his own. Following her around Madrid, he catches her with a friend of Muriel’s, Dr. Jorge Van Vechten. What is odd about her affair, though, is its passionlessness; indeed, Muriel had even told her, that night De Vere witnessed their confrontation, that he didn’t care if she slept with other men.

After Muriel, curious about a rumor from the Franco era, eventually asks De Vere to investigate Van Vechten’s past, De Vere becomes truly entwined in the couple’s lives, and that of their circle. This is classic Marías: the narrator possessing an outsider’s obsession, which he pursues to an uncomfortable end. It’s similar to some of his finest novels, A Heart So White and Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me, and to his most recent, The Infatuations. These novels unpack universal peculiarities of life—innocence or dying a “bad” death, for example—and pull back the layers to expose what lies (in both senses of the term) beneath. What makes Marías one of the best novelists in the world, and a regular in the Nobel betting odds, is his striking ability to find those facets of our lives that, with enough peeling, display some of the most uncomfortable realities of being a human. Marriage and love, for example, prove to be rich, frequent victims.

De Vere’s meddling escalates. To say much more would be to spoil the last fifty pages, with plot twists probably unmatched in any previous Marías work—but, essentially, De Vere repeats the mistakes of his elders. The pleasure here lies less in guessing what will happen and more in the circuitutious path to get there. For this is, indeed, a Javier Marías book—be prepared for a lot of lengthy digressions, detailed examinations of minutiae, things that seem generally irrelevant and try one’s patience. Thus Bad Begins has its share of these, perhaps more than in his best books, but many things that seem irrelevant are actually relevant, and the payoff in the end is just compensation.

In typical Marías fashion, this book does not only expose the personal foibles and naiveté of its characters, but also Spain’s attempt to recover from the death of its dictator—from it searching, as a country, for how to move on. In that way it does feel like a “real Spanish novel,” at least more so than The Infatuations. As Muriel says to De Vere:

“We just have to accept that this is a grubby country, very grubby. For decades we’ve rubbed along together, what else could we do, and we’ve been obliged to get to know each other. Many of those who behaved badly then, behaved well in other circumstances….Who hasn’t committed some vile deed (not political, but personal), and who hasn’t also performed acts of great kindness?”

Muriel’s generation has a Franco hangover. (Indeed, Van Vechten, who is of the same generation, “[i]gnored the passing of time, as if it were so familiar that it wasn’t worth devoting a single minute to bemoaning or pondering it.”) Their sins, however, have a lingering effect on De Vere and the later generations: Marías keeps drawing a contrast between De Vere—a young man of 23—and the rest of the characters, who are all at least a generation older. Readers don’t have to be familiar with Francoist Spain’s restrictions to glean something of the national mood; it’s also strangely appropriate that the novel’s release, a week before the 2016 U.S. Presidential election, elicits parallels that not even Marías could have planned.

Margaret Jull Costa, who also translated Mariás’s Your Face Tomorrow Trilogy and The Infatuations, provides steady work here again. Of his translators, she renders Marías writing the most engaging and immediate. At his best, Marías’s prose is the voice in your head when it’s the morning and you’ve had too much coffee: clear, sharp, and thinking over everything twice at twice the normal pace.

Thus Bad Begins, which takes its title from a line in Hamlet, is a fine novel about the myriad negative consequences of our own faults and mixed motivations. “I must be cruel only to be kind,” Hamlet says, at one point, to Gertrude. The characters here would understand quite well what Hamlet means when he finishes the couplet: “Thus bad begins and worse remains behind.” Spain would legalize divorce one year after the book takes place, too late for some, too early, perhaps, for others. It can also get worse, this book bleakly reminds us, even when it gets better.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction.

©Literal Publishing

Posted: May 18, 2017 at 9:54 pm