A few days ago, CM Mayo´s blog posted “Traven’s Triumph,” the English original of Timothy Heyman’s essay which was first published in Spanish in Mexico’s leading literary magazine, Letras Libres, in 2019, the 50th anniversary of Traven’s death. This week follows up with a Q & A with Heyman, who lives in Mexico City, where he co-administers the B. Traven literary archive together with his wife, B. Traven’s stepdaughter, Malú Montes de Oca de Heyman.

C.M. MAYO: Which is the first of the many works by Traven that you read, and what did you think of it?

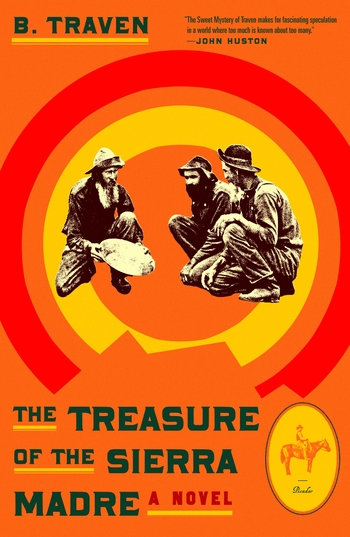

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: The first Traven work I read was TheTreasure of the Sierra Madre just after marrying Malú, his stepdaughter, in 1981. The main reason was that I had heard of it. I had seen the movie and enjoyed it, but knew nothing about Traven’s biography, partly because at that time there were no satisfactory biographies in English. The only good one, by Karl Guthke, was published in English in 1991, 22 years after Traven’s death in 1969. My misty watercoloured memory is that it was a well told cowboy tale with a Chaucerian touch. As a still somewhat bookish Englishman, I had never read a Western novel, but only seen Western movies. I could not help comparing it with Chaucer’s “Pardoner’s Tale,” and considered it very well constructed with a very ingenious final twist, in many ways more interesting than Chaucer.

C.M. MAYO: Which is your favorite of all the Traven novels, and why?

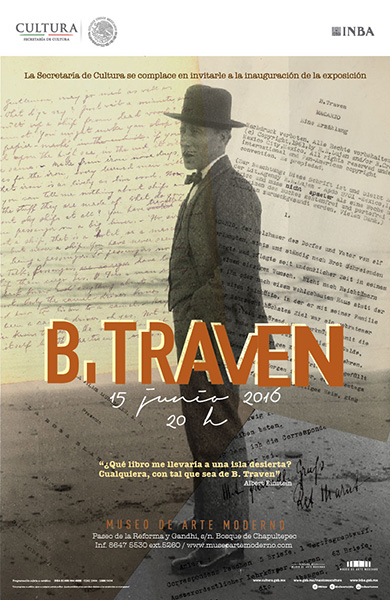

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: This is a very difficult question for me, owing to my personal involvement. Malú lived with Traven from an early age, and her mother Rosa Elena Luján (Chelena) was his only wife (she married Traven in 1957, having begun to work as his translator in 1953). I have therefore been steeped in Traven’s life and work for a long time. More recently, when there was the first ever Traven exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City in 2016, I understood better the dimension of his life and work (looking at the show as an outsider). I became even more interested in him and realized I was in a unique position to study him, both because I know something about German culture (including the language) and because I have privileged access to his Estate.

Like many, I was intrigued by the “mystery” and began by piecing together his life from his work, and his work from his life. I have come up with what might be considered an original synthesis of proofs of the identity he revealed to Esperanza Lopez Mateos, his translator, and the cousin of his best friend in Mexico, the cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa. I believe that there is strong evidence of Figueroa’s revelation that he was Moritz Rathenau, the illegitimate son of Emil Rathenau (1838-1915), one of the most important businessmen during the era of Kaiser Wilhelm. Rathenau founded the first and most important electricity conglomerate, AEG, in Germany in 1888. His legitimate son, Walther Rathenau (1867-1922) succeeded him as head of AEG and became Foreign Minister of Germany in 1922, the most successful Jew in German political history, until his assassination in June of that year by a group of antisemitic far right activists, a seminal event that was considered the beginning of the Holocaust in Germany. This provenance would make Traven a member of the one of the most important families in Germany and could also shed important light on his work.

Traven hid his identity for many reasons, and became famous for the mystery of his identity, all of which I analyze in an article that was published in Letras Libres, a leading Mexican literary magazine, in 2019 to commemorate the 50thanniversary of his death in 1969. But people were mainly interested in his identity because of the quality of his works. He wrote 15 books and innumerable short stories, has sold more than 30 million books in more than 30 languages in more than 500 editions. More than 8 novels have been turned into movies or TV series, mainly in three languages, English, German and Spanish.

As I have explored his life and work more deeply, I have come to the conclusion that Traven is a genius. Extraordinarily versatile in word and deed, he was larger than life, and did not only deal with different subjects, but different genres, beginning with short stories, moving to novels, and then in the latter part of his life to the relatively new art form of the cinema, which was emerging in Germany in the 1920s when he was still living there. Not coincidentally, the epicenter of quality cinema transferred from Berlin to Hollywood, dominated by Central European emigrés, in the early 1930s, at a time when he was living not too far away in Mexico.

In response to your original question, if we think of creative people who we call “geniuses” it becomes difficult to choose a favorite. What is your favorite work by Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Mozart, Beethoven, or Picasso? In any art form, most geniuses’ work is divided either by genre or by period. In the case of Shakespeare, therefore, it might be more sensible to ask which is your favorite comedy, tragedy or sonnet. In the case of painters or composers, maybe we should ask which period you prefer, Beethoven’s first two symphonies (his first period), his middle symphonies (3 to 8), or his last, glorious one (9): idem for Mozart, or Picasso.

Traven is different from the geniuses I have mentioned above in terms of his development in time and space. When he was Ret Marut in Germany (1882-1923), he was an actor, director, and sometime writer of short stories, plays and novels, then became a political activist and producer of an anarchist magazine. That was temporally almost exactly the first half of his life. When he became B. Traven (1924-1969), and burst on to the literary scene in Germany, he was a fully-fledged writer, having been shocked into fusing his personal experience with his pent-up literary genius.

I consider the best (i.e., my favorite) works by B. Traven to be The Death Ship (published 1926), The Cotton Pickers (1926), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,and the six books of the Mahogany cycle (1930-1940).

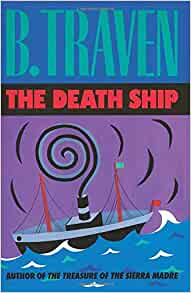

The Death Ship is clearly autobiographical and tracks his voyage from Germany to Mexico. But it elevates the personal story to a discussion of identity in the modern world: the lack of the papers necessary to move from one country to another, the power of the state over the individual through petty bureaucracy, the plight of migrants who are victims of both bureaucrats and employers, the general theme of exploitation of the lower classes by unscrupulous employers. The reality and metaphor of the merchant marine is an extreme example of the riskiness of life and employment, as the hero is subject to the arbitrariness not only of countries and companies, but also of the climate. The book has a hero, Gerald Gales (beginning the constant use of the storm metaphor) and a plot, the hero’s journey to a destination, which is made deliberately ambiguous. The narration is spiced with humor, satire and savage criticism of the way the world is organized. Although in the end, apparently, the protagonist survives an extraordinary shipwreck, described in tremendous, realistic detail in the book’s climax, through its overall theme and tone, it could be considered a tragedy.

The Cotton Pickers is also autobiographical, about what happens to the hero when he arrives in Mexico. A hobo, a vagabond, he tries his hand at everything, whatever he can, in and around the town of Tampico, a magnet for many people from around the world because of its oil boom. The book describes how he tries five jobs: cotton picker, oilfield roustabout, cattle driver, baker and waiter. The skills required for each job are described in minute detail as is the socioeconomic reality of each job and the worker’s relationship with his boss, who typically exploits him. The humor, satire and social criticism remain, but because of the subtle irony of its ending this book could be considered a comedy.

Taking the two books together, if The Death Ship is Traven’s Iliad, The Cotton Pickers is his Odyssey.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, on rereading, is more than a Western novel with a Chaucerian twist. It is an extension of The Cotton Pickers, with a vagabond hero, not autobiographical, but also set initially in Tampico. Having tried everything, he decides on gold prospecting, forms a group of three to start a business (a mine) in the middle of nowhere. Fraught with peril due to inclement conditions and the ubiquity of Mexican bandidos, the group find the gold, mine it, hide their trove, bring it down from the mountain in spite of the bandits, then lose everything. A classic novel, it became a classic movie.

The six Mahogany books are not autobiographical. They describe with extraordinary empathy the conditions in and around the Monterías, logging camps, in the state of Chiapas, where Traven (having been on an expedition to Chiapas in 1926) returned to the southernmost state of Mexico and spent most of his time there in the 1930s. Before reading them, it might seem difficult to imagine how Traven could write 6 books, apparently on the same subject: the exploitation of Indian workers in the Monterias (Carreta; Government; March to the Montería; Trozas; Rebellion of the Hanged; General from the Jungle). But each book focuses on a different aspect, normally with a different hero or heroine, although there is some overlap. Carreta on the oxcart drivers and on how they drive the oxcarts to the Monteria, Government on how the state, the towns, and the monterias are managed and how the workers are treated, March to the Monteria on how and why workers are recruited and how they are literally driven to the Monterias, Trozas on how the logs are moved from the monterias to the river, then down the river to their port of embarkation to be taken to world markets, Rebellion of the Hanged on how the workers eventually get their revenge on their bosses, and General from the Jungle on how they march back to civilization led by a natural general from among their number and defeat their bosses’ enablers, taking over haciendas and towns. Meanwhile, there are links through several characters between the different books, arriving at a climax with the last two books when the workers take over. The series forms an epic masterpiece.

C.M. MAYO: Which do you think is Traven’s most underappreciated novel?

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: The Cotton Pickers, for the reasons implicitly provided in the previous section.

C.M. MAYO: Have there been any notable and particular challenges in bringing his works from German into English? (Did he write all of his novels originally in German?)

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: Traven originally wrote his novels in German, for the German public. His first novel, The Cotton Pickers (Der Wobbly in German), was originally serialized in Vorwärts, the newspaper of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) in 1925. It was published the following year 1926 as a book, as was The Death Ship by the Büchergilder Gutenberg. Büchergilder was a publishing house and book club set up in August 1924 by the Educational Society of German Book Printers (Bildungsverband der deutschen Buchdrucker). In the words of Guthke his biographer, “Büchergilde not only ‘made’ Traven – Traven also made the Büchergilde.” Büchergilde gained its greatest visibility in the literary world as the publisher of B. Traven. By the end of the 1920s 100,000 copies of The Death Ship were in print and by 1936the total circulation of Traven’s works in German alone was half a million, covering the German, Austrian and Swiss markets. This was considered an extraordinary success, not least because Traven’s books were not typical “adventure” stories but had social and political content.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, the German market dried up, because Traven’s books were banned and Büchergilder was forced to emigrate to Switzerland. Traven had already considered the US in 1929 and signed a deal with Doubleday for the rights to the US and British markets not only for the books but also significantly for film and theater. After various disagreements, mainly about marketing strategy where he preferred anonymity and did not want to be “hawked like cigarettes, car tires, toilet soap, toothpaste, and the latest mattresses,” he bought back the rights from Doubleday. Then, in 1933, he was discovered by Alfred A. Knopf and reached an agreement with him to publish his books in English. There is an extraordinary exchange of letters between Knopf and Traven in our archive which demonstrates that Traven was not an easy author to deal with, as he set the conditions of their collaboration.

Traven translated his own books into English. He was lucky to have Bernard Smith as his skilled and sympathetic editor at Knopf, and Traven gave Knopf permission that Smith could edit his books if grammatical, syntactic or orthographic changes had to be made. Smith considered the text so Germanic that he had to “treat” at least 25 percent of the text. Meanwhile, Traven in order to preserve his anonymity (as not German) insisted that his books be stated as being “the English originals.” Meanwhile it is clear from the English texts that Traven’s mother tongue was not English, although he spoke it well, adding strength to my view that his mother was a native English speaker (Gabriel Figueroa stated that his biological mother was an Irish actress, Helen Mareck).

C.M. MAYO: The new editions of B. Travens’ novels just out with Farrar, Straus & Giroux, did these involve new translations from the German? Can you talk about this in any detail?

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: Two books were recently published as ebooks by Farrar Straus this July 2020, the first ever ebooks in English, as part of our agreement to make all his works available in English as ebooks over the next 18 months: The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Aslan Norval, his last novel (1960). Treasure was also published as a Picador paperback. Treasure is the original Traven translation edited by Smith for Knopf in the 1930s. We are excited that Farrar Straus decided, as part of the package, to publish Aslan for the first time ever in English, fifty years after Traven’s death: imagine “discovering” today an unpublished novel by George Orwell, or Ernest Hemingway! It was translated by Anabel Aliaga-Buchenau, Professor of German at the University of North Carolina.

C.M. MAYO: Of all Traven’s novels, which one do you think best stands the test of time– and has the chance to be read into the deep future?

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: The novels which I mention (above) as my favorites.

C.M. MAYO: Do you think Aslan Norval will stand the test of time?

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: The book is unlike any of the other novels written by Traven. It is neither about the oppressed or unemployed white men, as the case with Cotton Pickers, Death Ship and Treasure (written in the 1920s), or the Mahogany cycle about oppressed indigenous people in Southern Mexico (written in the 1930s). It is about a young, rich, American girl in her twenties with experience in Hollywood (married to an older man), who wants to build a canal across the United States and hires an engineer, a Korean War veteran, to help her. The ambiance is very US 1950s, when Traven wrote the book and it is a wry satirical commentary on US capitalism, politics and foreign policy at the time. It is a 50s period piece, somewhere between a Cary Grant comedy, and a film noir. Traven became friendly with Bogart on the set of Treasure in 1947 and, quite possibly, might have imagined casting his wife Lauren Bacall (who was also on the set) in an Aslan movie. I enjoyed it and found it particularly interesting as it is autobiographical and reminiscent of Traven’s first unpublished book, The Torch of the Prince written in German under his earlier pseudonym Ret Marut, about an engineer who wants to build a railway in Vietnam, set in 1900, the time when Marut travelled in the Far East. Coming back to your original question, 3 months after publication, it is probably too early to say whether it will stand the test of time among the reading public in general.

C.M. MAYO: Having handled his vast correspondence, what is your sense of Traven as a creative entrepreneur?

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: Traven was an entrepreneur in many ways. In Germany, he first appears under the name of Ret Marut as an actor, based mainly around Cologne and Düsseldorf but also with a travelling theater company. He also appears to have done some directing. When he settled in Düsseldorf with an important theater company from 1913 to 1915, he was closely involved in the formation of a theater school. At the museum of that theater I personally examined the prospectus he wrote for the school, specifying the school’s curriculum, what was required of the teachers, and who could be the donors. He was clearly involved in the design of the cover of the prospectus. After the beginning of WWI, he moved in 1915 from Düsseldorf to Munich, and became more involved in political activism, having become a declared anarchist. He started an anarchist magazine Der Ziegelbrenner which he started publishing from his Munich apartment in Clemensstrasse 84 in 1917. Following his escape from the death sentence in Munich on May 1, 1919, he continued publishing it when he went underground until 1921. As publisher, he was responsible not only for the content which he wrote entirely himself, but also for design, printing, distribution and finance.

When Traven arrived in Mexico in 1924, he earned a living in the ways described in The Cotton Pickers. Meanwhile, he already began to write short stories, some of which were published in Vorwärts before the serialization of The Cotton Pickers. After establishing his publishing relationship with Büchergilder in 1925, he is continually interested in the sales of the books and even initiates methods of interesting his readers in Mexico, by offering prizes consisting of Mexican artefacts such as necklaces and dolls, which he mentions in his letters to the publishers. We have some of these objects in the Traven archive.

The Doubleday deal struck in 1929 (mentioned above) shows that Traven was already careful not only to grant literary rights, but also rights to movie and theater versions. In his correspondence during the 1930s interest is shown in adapting his works to these media. When war broke out in Europe in 1939, Traven realized that he could not rely only on the US market. Coincidentally he was approached by Esperanza Lopez Mateos, who had read one of his books in English, and wanted to translate him into Spanish. His initial misgivings were overcome when she sent him a translation into Spanish of The Bridge in the Jungle. He liked it so much that it was his first authorized translation into Spanish and published in Mexico in 1941. Esperanza then became his official translator and translated most of his books from English into Spanish, until her death in 1951.

Traven had for a long time wanted to make films out of his novels and Esperanza introduced him to her cousin Gabriel Figueroa, the most important Mexican cinematographer until that time, and it was through Figueroa that Traven made the contacts in Hollywood that led to the making of the movie in 1947 by John Huston of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, starring Humphrey Bogart and Walter Huston, John’s own father, which won 3 Oscars in 1948.

“it was through Figueroa that Traven made the contacts in Hollywood that led to the making of the movie in 1947 by John Huston of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, starring Humphrey Bogart and… which won 3 Oscars in 1948.

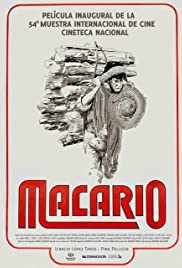

Following that breakthrough year, Traven was able to realize his dream of turning several more of his works into movies as filmscripts, in both English, German and Spanish. His most important German movie was of The Death Ship (1959) starring Horst Buchholz and Elke Sommer directed by Georg Tressler, long considered a cult masterpiece. His most important movie in Spanish was Macario (1960), which was the first Mexican movie ever to be nominated for the Oscar for best movie made in a foreign language. Details of the negotiations for these movies are in the archive.

During the 1950s, Traven complemented the various entrepreneurial skills he had already shown, producing material, adapting it to different genres, expanding into different markets, translating into different languages, surviving changes of publishers, representatives and translators, by beginning a proactive marketing campaign for his works with the publication of the BTNews in English and BTMitteilungen in German, that regularly informed the public about his works.

C.M. MAYO: Traven really must be considered a Mexican novelist. Can you talk a little about his attitudes towards and feelings about his adopted country?

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: Having been German as Ret Marut until he arrived in Mexico in 1924, Traven officially obtained papers as a Mexican citizen in 1951. So technically he was both a German and Mexican writer. If we were to take his beliefs into account as expressed in The Death Ship, he did not believe in nationalities or nationalisms, but would probably have considered himself a “universal” writer, or global in today’s terms.

Meanwhile, it is clear from his life and his writings that he loved Mexico. He liked it, first of all, as a place. He had acquired an affinity for the tropics as in his seafaring days as a very young man (until 1907) he had travelled by boat to the Far East. From his first unpublished novel The Torch of the Prince (Die Fackel des Furstens) it is likely that he spent quite a long time in Vietnam. He continued to eat with chopsticks when he made a home with Malú’s family from 1957 until his death in 1969. After living in Tampico in the 1920s, Traven spent most of the 1930s in Chiapas. As Mexico City filled up with emigrés from Europe in the late 1930s and during WWII Traven bought a property in Acapulco (Parque Cachú) and spent most of the 1940s there. He returned to live in Mexico City in the 1950s and 1960s.

“He loved Mexico… After living in Tampico in the 1920s, Traven spent most of the 1930s in Chiapas. As Mexico City filled up with emigrés from Europe in the late 1930s and during WWII Traven bought a property in Acapulco (Parque Cachú) and spent most of the 1940s there. He returned to live in Mexico City in the 1950s and 1960s.”

It is clear that Traven formed an enduring affection for the Mexican people, and showed uncommon empathy for their lives and feelings, as demonstrated in his novels, the most touching being Bridge in the Jungle and Macario, with the extraordinary healing scene in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre also particularly memorable.

Traven was notoriously a recluse. But shortly after arriving in Tampico in 1924, he had gone to Mexico City in 1926 and studied Mexican culture at the UNAM, Mexico’s national university, and made several friendships there and in the city. We know that his friends in the 1920s included Edward Weston, the photographer, along with Weston’s girlfriend, Tina Modotti, and the two of them taught him photography: we had a collection of Modotti photos in the Traven Estate which is now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. This enabled him to be the official photographer of the UNAM expedition to Chiapas in 1926, and to produce his own excellent photographs (we have more than 1,000 negatives in our archive). His enduring interest in technology (supporting my belief about his parentage) is attested by his fascination with flying (he took flying lessons in the early 1930s in the US, and we have an airplane manual of that period in our archive). Through Chelena, he was friendly with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo as well as David and Angelica Siqueiros and other intellectuals such as the playwright Rodolfo Usigli. Through Esperanza Lopez Mateos he became close to her brother Adolfo, who was President of Mexico from 1958 to 1964, and had a direct telephone to the presidency installed in Traven’s house. Through Gabriel Figueroa, her cousin, he was friendly with many members of the Mexican film community.

“We know that his friends in the 1920s included Edward Weston, the photographer, along with Weston’s girlfriend, Tina Modotti, and the two of them taught him photography“

Finally, when Traven married Chelena, Malú’s mother, in 1957, he considered her two daughters, Rosa Elena (Chele) and Malú as his own, and they considered him their father. He underscored his stormy life by constantly referring to storms, not just in The Death Ship, his first important novel, but also when he formed a publishing company in 1943 with Esperanza Lopez Mateos, to be called Tempestad (storm). As if to stress his final tranquility he referred to his final home as a ship, he was the “skipper,” Rosa Elena was “first” (mate), Chele “second” and Malú “third,”

In an unpublished letter to Malú who was studying in Paris, written in 1967, he sums up his life:

“My dear Malú. Again you’ll have to put up with these crow’s feet which I’ve to use in communicating with you because as I told you before I don’t want to molest that old machine which has been so very faithful for many years, now on the high seas, now in the very midst of dense jungle, now with heavy rainstorms pouring down on the poor thing, that’s so very tired of hard work during so many years.”

In the same letter, referring to Malu’s travels in Europe, he says

“There is nothing like Mexico. If you didn’t know it before, you know it now.”

C.M. MAYO: Are there plans you can share for the Traven archive?

TIMOTHY HEYMAN: We plan to use the archive for at least the next two years to be able to write the definitive biography that he deserves and perhaps turn it into a movie or a TV series. Meanwhile we are exploring alternatives for the Traven archive in the three obvious countries: Mexico, Germany and the United States. Our decision about which institution should house the archive will depend on several factors: capability for storage and conservation, ability and interest to conduct continuing research into his life and work, ability to provide access and encourage interest in his life and work among the broadest possible public.

C.M. Mayo is the author of Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual(Dancing Chiva, 2014) which is translated by Agustín Cadena as Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución mexicana: Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita (Literal Publishing, 2014). Her website is

C.M. Mayo is the author of Metaphysical Odyssey into the Mexican Revolution: Francisco I. Madero and His Secret Book, Spiritist Manual(Dancing Chiva, 2014) which is translated by Agustín Cadena as Odisea metafísica hacia la Revolución mexicana: Francisco I. Madero y su libro secreto, Manual espírita (Literal Publishing, 2014). Her website is

![Entre Pink Floyd y el INAPAM [1]](https://literalmagazine.com/assets/patti-620x350.png)