Where is the Problem?

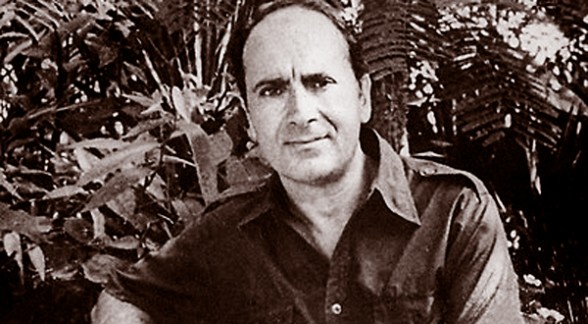

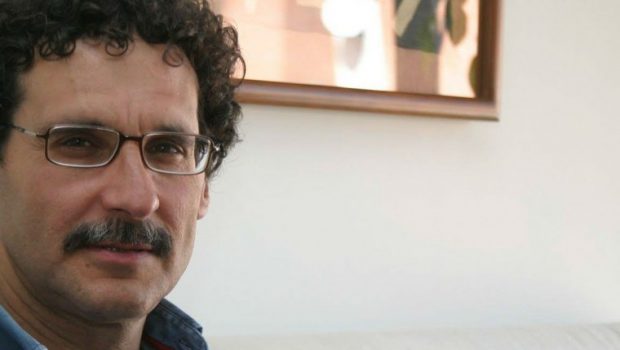

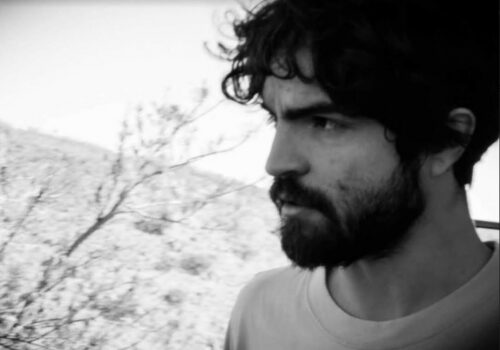

Rogelio García-Contreras

Robert Fisk

Robert Fisk

The Age of the Warrior,

Selected Essays, Four Walls Eight Windows,

Barcelona, 2008, 522 pp.

“Get rid of the written language and history seems less dangerous” (p. 342). Through an impressive journalistic account of current Middle Eastern politics Robert Fisk reminds us of the importance of preserving an impartial and unbiased account of history. Get rid of written language and history will be subjected to the limitations of memory. Let the right to free press die, and the injustices of this world will not only be institutionalized through the automatic consent of millions, but they will fi nd enough fertile ground to establish themselves as perfectly normal occurrences.

In and by itself, The Age of the Warrior is living testimony of Fisk’s heroic like efforts to keep the flame of fair and honest journalism alive. An implacable witness of human tragedy, Fisk offers priceless accounts of several dark passages in current human history. With a magnificent prose and outstanding intelligence, the journalist demands our attention, the analyst challenges our convictions and the humanist take part in our conscience: To what extent are we the origin and means of the London bombings? To what point the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the result of a collective and schizophrenic neurosis? Is the Middle East a refl ection of our insatiable greed and pathetic shortcomings? And then the central premise of Fisk’s insightful account: what is history if not a justification of the present, unless of course we can emancipate it from a recurrent manipulation— and ill entitlement—of pure and simple facts. As the say goes, Fisks reminds us of a useful thought in today’s mass media dominated world, “everyone is entitled to his opinion, but not everyone is entitled to his facts”.

In The Age of the Warrior, aggressively passive societies chronically obsessed with the glamour and exuberant nature of superfi cial and disposable patterns of beauty, consume these patters on a daily basis while making the arbitrarily circumstantial choice of ignoring the concrete antithetical manifestations of such collectively and conveniently accepted patterns. Thus, mass media fabricated heroes become the nemesis of infamous terrorists, and well tested patriots become the antithesis of the victims of War. In a world where any form of national or supranational authority cannot be comprehensively criticized by the average observant of “the facts according to CNN”, Fisk’s work becomes as important as it could turn out to be epic.

But perhaps the most important contribution of this exceptional collection of articles and editorials is the author’s commitment to convey some truth into a world where the steady manifestation of unfairness and injustices makes most of us jump into the conclusion that acting and behaving as a warrior is not only normal but necessary. Under such circumstances, the noble ideals of freedom and democracy for all are nothing but a porous, weak, and deficient speculation. The Age of the Warrior is a reminder of our pitiable inability to be entitled to our own facts. The search for serious, honest and committed journalism in Fisk’s work is essential for the basic democratic principle of selfcriticism. Self criticism, however, is not a synonym of civil political empowerment. As Robert Fisk suggests: sometimes the problem resides, precisely, in the critique.

Posted: April 15, 2012 at 4:39 pm