Burning Out His Fuse Up Here Alone

So Mayer

Floating in a swimming pool has become a new image of wounded masculinity: from the opening of Creed II to Pain and Glory via Rocketman, male protagonists surrender themselves to the water as they both experience and heal from pain, physical and psychic. Add Ad Astra and its variant of the telling image of a man suspended from gravity, falling into himself: a rocketman, in Elton John’s words, burning out his fuse out here alone.

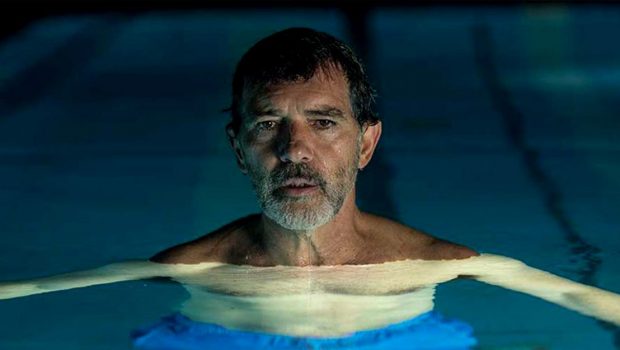

In Dexter Fletcher’s 2019 biopic of John, the staging of the musical number “Rocketman” begins with John (Taron Egerton) in a Los Angeles swimming pool that attains an impossible depth, “high as a kite” and low as depression. It seems like the world’s biggest star has reached his suicidal nadir, and it is only because we know his celebrity story that we are reassured it will end with him “still standing” (the film’s final musical number, which cleverly blends new footage with the original music video). While the hero’s crash is a classic Act II device, this detail from a mainstream film takes on new meaning when set against a strangely similar story, albeit told differently, from the arthouse: Pedro Almodóvar’s most recent film, his most critically acclaimed for a decade, Pain and Glory. Both films celebrate queerness through their extraordinary use of vibrant colour and sensual textures in costuming and décor

Almodóvar told Henry Chu for Variety that, despite critics’ assertions about the main character Salvador Mallo, a queer Spanish filmmaker who made a shocking, punky film in Madrid in the 1980s:

This is not a biopic of me, not even a portrait. Obviously this is a film that starts off with me. I’m at the root of the script I started writing…

Look at the first shot of the film. Antonio’s character is suspended in water, just floating there, with no gravity at all. That image is from my own life, because during the summer it was my favorite place to go, to put myself in water and just hang there, weightless, not feeling my body or any tension… It’s a luminous memory, totally opposed to the dark period that the main character is going through.

The filmmaker’s luminous memory acts as a suspension, for Mallo, from his intense, chronic physical pain: a form of physiotherapy, psychotherapy (it prompts childhood memories), and–for audiences–an aesthetic and sensory immersion that brings us close to the character, into his experience.

Like Elton John, Mallo is a gay man wrestling with a childhood in a repressive country and era, and what that means for his adult desires and creativity. Like John, Mallo experiments with drugs as a form of pain management, before seeking medical help from a caring doctor who enables him to reconnect with his child self. Both John and Mallo give themselves over bodily into another person’s hands to be cared for and–in a religious sense that is more palpable in Pain and Glory–to be saved. The protagonist is called Salvador, but he is in fact saved, first by renewing a friendship with the lead actor of his first film, then through an encounter with an ex-boyfriend, Federico, whose story he has staged, and finally through surgery. The medical experience reminds him of a childhood illness: a fever he contracted that he associates with his first sight of a desired naked male body.

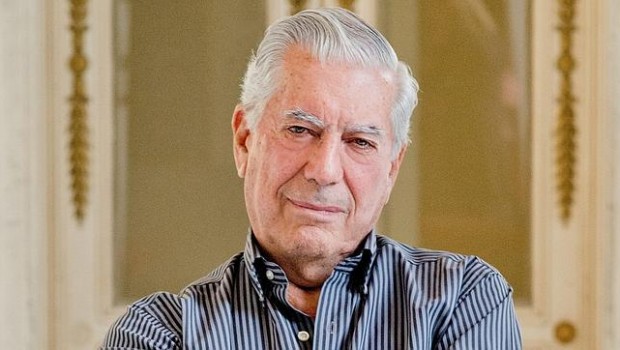

This gorgeous, intense scene, with its cascades of water as handyman Eduardo, who the young Salvador taught to read, washes himself at a tin tub in the family kitchen, is the climax of the film: of Salvador’s realization that desire and shame have fused in him, burning him up so he feels alone. Both Pain and Glory and Rocketman take on and contest the myth of the misunderstood artist-martyr, particularly the queer artist-martyr, who carries our suffering for us, acting as our sacrificial salvation. Both films refuse that path, and the idea that one has to suffer for one’s art, instead unpicking and liberating the deep cultural taboos on childhood sexuality, the feeling body, and the desiring gaze. Mallo keeps company with gay writers such as Eric Vuillard, reading their work in a search for a new language to describe what is arising from reckoning with his chronic pain.

As an adult, Mallo finds himself subject to painful and unprompted choking fits: a classic hysterical symptom of maintaining one’s silence, more usually associated with women in Freud’s writing. Unusually for Almodóvar’s recent work, Pain & Glory does not depict any sexual violation of women’s bodies; Mallo’s choking fits and lower back pain, as well as his broken heart and a veiled reference to childhood sexual abuse by a priest (which seems to refer back to the flashback narrative in Bad Education), suggests that the sexual violation was always a displacement, a punitive refusal to look hard at the pain of queer sexuality for male bodies. And it is partially through turning to the experience of women and femininity–through his memories of his mother (Penelope Cruz and Julieta Serrano), and through accepting the kindness of his friend and producer Mercedes (Nora Navas)–that Mallo finds his way to salvation.

And, despite the film not being an auto biopic, there is a beautiful doubled reference to one of Almodóvar’s close friends, Argentinean filmmaker Lucrecia Martel, whose early films he and his brother executive and co-produced, respectively. Mallo’s ex, Federico, tells him that he lives in Buenos Aires and has married an Argentinean woman called Lucrecia. Earlier in the film, Mallo and Crespo (Asier Exteandia), his former collaborator, watch the famous closing scene of Martel’s second feature, La niña santa (The Holy Girl), in which the two schoolgirl protagonists–who are about to get in terrible trouble with their mothers for acting on their emerging sexual desire (although not with each other)–backstroke in diagonals across and around a hotel swimming pool, the camera suspended above them. It’s as if Mallo is taking the hint: there is a way to depict adolescent desire that is considered socially transgressive, without martyrdom or punishment.

The swimming pool is a marked space for obliquely exploring queer teenage transgression, both sexual and social, in Martel’s first three films, as it is in Céline Sciamma’s Water Lilies and Tomboy. The pool is also a screen for memories, a place of being seen and of seeing, of transparency and ripples that hide bodies. It is the site of Mallo’s desire–to look at, perhaps to be, and certainly to feel like (as in: feel himself to be, have feelings of similar intensity to) Natalie Wood in Splendour in the Grass and Marilyn Monroe in Niagara. Both Hollywood actresses famously burned up (Monroe doing so “like a candle in the wind,” in John’s words) in the intensity of their feelings, in the impossibility of being a woman in a patriarchal world, and it is these figures that Mallo selects as his expression of the cinema–and perhaps of himself– hat captivated him in childhood for the projections in the monologue about Federico that he writes and that Crespo performs.

In Pain and Glory, Crespo makes a passing reference to having 1980s magazine pictures of Mallo wearing a dress. Almodóvar’s films have long depicted trans women who were part of his social world in early 1980s Madrid and onwards, often in a spectacular or hystericised register; there are no explicitly trans characters on show here. But Almodóvar’s comments about trans recognition in Spain to Chu suggest that the director is working with and towards a new vision of gender identity, on screen and possibly personally:

Where we’ve certainly made a lot of progress is in gender reassignment. In the past, a trans person had to certify their new identity in front of a forensic doctor, to demonstrate that your organs belonged to the gender you wanted to be known as. What a terrible and humiliating thing. Now, you don’t even need to have, let’s say, the final operation, which is a huge step forward. To feel as though you’re a man or a woman doesn’t depend on whether you have a vagina or a penis; it depends on something much more profound.

The film is at its most touching in depicting Mallo’s relationship with his aging and dying mother, in its suggestion that he has displaced her symptoms onto his own body. It is as if he is suffering sympathetically in a sense to keep her alive after her death; and that through fully embracing his queerness, he is able to then translate that identification into the film-within-a-film we see him directing in the final moments.

Like Elton John, Almodóvar and his ensemble burst into the international cultural consciousness by telling radical, sexy, genderfluid stories that have enabled the next generations of young queers to feel less alone when they feel like burning up. As Maria Delgado argues for Sight & Sound, the film shows that Almodóvar still “aligns him[self] with progressive voices in a country split across opposing political lines,” recreating a piece of graffiti in one scene that refers to the trial for gang rape that galvanized both Spain’s feminist movement and its heteropatriarchal far right.

In Pain and Glory, we see a survivor–of Francoism, of the AIDS/HIV epidemic, of austerity, and of the dangers of age’s creeping conservatism and of getting stuck in an artistic rut–speaking with plangent frankness about both the ageing body and its connection to the youthful fever inside it. The water of the swimming pool is not there to douse the flames, or even provide respite from the fire: instead, it is an equal and opposite sensory experience, the intensity of reflection; of survival; of letting go; of return.

So Mayer is the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism and Documentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

So Mayer is the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema, The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism and Documentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

©Literal Publishing

Posted: October 16, 2019 at 8:09 pm