Empty Pool by Isabel Zapata: The Powerful Essayists of Latin America

Empty Pool de Isabel Zapata. Las poderosas ensayistas de Latinoamérica

Adriana Pacheco

A simple internet search about the tradition of writing essays in Latin America reveals a long list of names like: José Martí, Andrés Bello, Octavio Paz, Alfonso Reyes, Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, Lezama Lima, and the indispensable Carlos Monsiváis; all of them men.

Of course, the landscape changes when the search includes the term “women essayists” or “female writers.” A few names appear—though not many always the same ones— and they are often mentioned briefly and without depth. ChatGPT shows slightly more creativity when asked for “names of Latin American women essayists,” providing a list of ten writers that includes Silvia Molloy, Marta Traba, and Victoria Ocampo, among others, but still largely repeating that same list of familiar names.

The results from these online and ChatGPT searches highlight the vast gaps and biases in how the literary genre of the essay is understood and recognized. First, it reveals the void in acknowledging and identifying women writers who have significantly contributed to the field. Second, it betrays the persistent need to assign gender to literature, requiring one to specifically ask about women to obtain results, which should not be necessary when discussing literature as a whole. Third, it underscores the lack of a comprehensive survey of the literary landscape to identify contemporary writers and the countries from which they are writing.

Authors like Soledad Acosta de Samper, Clorinda Matto de Turner, Victoria Ocampo, Rosario Castellanos, Beatriz Sarlo, and the indispensable Margo Glantz and Angelina Muñiz-Huberman—along with many others from the Caribbean named in books like Mujeres ensayistas del Caribe Hispano: Hilvanando el silencio (Women Essayists of the Hispanic Caribbean: Weaving Silence, 2007)—are just glimpses of a genealogy of great essayists who inspire contemporaries such as Irene Vallejo, Betina González, Sonia Cristoff, Verónica Gerber, Jazmina Barrera, Vivian Abenshushan, and, of course, Isabel Zapata.

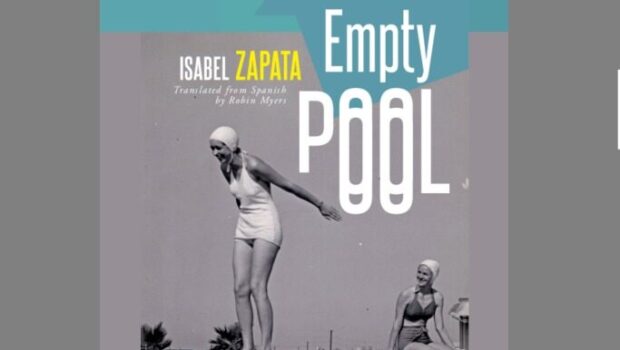

Isabel Zapata is who I want to write about today as my starting point into the conversation about contemporary literature. What prompted me to do so is the reissue of a gem of contemporary essay writing: Empty Pool. This reissue, now exclusively in English, comes from Hablemos, Escritoras and Literal Publishing—a press founded in Houston, Texas, celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. The book was originally published in a bilingual format in 2019 by Editorial Argonáutica under the title Alberca vacía (Empty Pool), and this edition features Robin Myers’ translation. Myers has also translated other works by Zapata, such as In Vitro (Coffee House Press) and A Whale is a Country (Una ballena es un país, Editorial Fonógrafo, 2024).

As with other books, getting Empty Pool to the United States and into the hands of English-speaking readers became an obsession for me from the moment I first read it in 2019 to prepare for my interview with Zapata. Reading it left me with that sense of empathy and learning that her works always evoke, as does her first novel Troika (Almadía, 2024), the story of a dog, a girl, and a caregiver.

This translated version of the book not only enriches the collection of translated literary works of superb quality from Spanish-speaking countries but also showcases the richness of contemporary essay writing in countries like Mexico. Voices like Brenda Ríos, Vivian Abenshushan, Liliana Pedroza, Marina Azahua, and Gabriela Jauregui exemplify contemporary Mexican essay writing.

Empty Pool is also accompanied by photographs that the author uses to explore themes such as the possibility of conversing with a mother who is no longer present through the notes she left in the margins of her books. “Reading the books of my mother means talking to her.”

The book also takes us on a journey through the work of notable writers to demonstrate that the way we read begins with how we organize and collect books in a library, an act in which book lovers reveal their eccentricities and how these change throughout their lives. “Library is a collection, and collection means a state of constant construction.”

This book can also be considered part of writings in the Anthropocene era, where many writers focus their gaze on animals and nature. The author returns to this theme, as she had previously done in her poetry collection A Whale is a Country, stating that literature can build bridges of empathy between humans and nature in a way that only literature can achieve.

These essays now take us to other animals: dogs, octopuses, birds, dolphins, chimpanzees, elephants. In discussing them, Zapata shows how humans are determined to speak about what we see, the ways we connect with them, and how they teach us about sentimental life or mourning our dead. The story told in the essay “A Brief Chronicle of Canine Virtues” is a good example, exploring the extent of dogs’ loyalty, only to suggest, tongue-in-cheek, that this may simply be a coincidence of their entirely animal and non-human behaviors—or that perhaps there’s something in us that idealizes their actions.

In “In Praise of Nosferatu,” she considers the possibility that an octopus’s intelligence may be close to that of humans, though our smallness will never allow us to fully understand it.

For me, as I grow older, nature and the animals that inhabit it become more meaningful. Birds hold a special place for me, perhaps because of their peculiar beauty, their rituals, or their enviable freedom, to see everything from a distance, from a far-off, aerial perspective. This fascination makes the essay “Notes on Birds” particularly beautiful, especially Zapata’s thoughts on the terms used to name them. For her, the correct term is ave rather than pájaro, as the former speaks of movement while the latter suggests stillness. “Ave makes me imagine the animal in the air, while pájaro makes me picture it perched motionless on a branch.”

Today, when cell phones have become repositories of images and proof of our modern obsession with capturing everything—I must confess that I have an absurd number of over 20,000 photos and videos on my phone—the essay “Against Photography” reminds us of the reflections of critics, thinkers, and writers on photography’s capacity to preserve memory. “More than preserving memory, photos replace it.” Zapata revisits the idea of the innocence of photography in selecting and capturing a moment as it happened and suggests that photographs actually extract a fragment of life. “There’s something predatory in the act of taking a photo.”

The theme of translation is fundamental in Zapata’s work. For example, she often mentions how fortunate she is to work closely with her translator, Robin Myers, who shares her perspective on language and deep knowledge of Mexican Spanish. Myers, in addition to being a translator, is a poet who lived in Mexico for many years, an experience that undoubtedly contributed significantly to her translation of Zapata’s and other Mexican writers’ works, such as Rosa Beltrán.

In Empty Pool, Zapata dedicates a section to translation, addressing it with irony—for instance, recounting how Nicanor Parra decided to translate Russian writers into Spanish despite not speaking Russian, or how Baudelaire translated Edgar Allan Poe without mastering English. This essay is both an acknowledgment of this complex and delicate art and an exploration of how it can create new worlds, as she notes about Ezra Pound, who went beyond translation to creation. “As a translator, Pound didn’t transform. He created.”

Just as translation can broaden our vision of the world, essays do the same: once you’ve read them, you’ll never see life the same way again. For example, after reading Empty Pool, I’ll never view a buffet the same. It will now be an image of our contemporary reality that confronts us, like all things modern, with the dilemma of choice, the doubt of unlimited combinations of dishes, the absurdity, ambition, and even ridiculousness of combining foods that never should have been together. In this essay, Zapata dialogues with other essayists who have questioned the use of contemporary practices, tools, and objects that make us social beings, as writers like Margo Glantz have done in essays about shoes or hair. “I am still overcoming my fear of making a fool of myself at a buffet.”

The essay “Silent Reading” is beautifully written, discussing how reading has changed over the centuries, from being something that is done aloud to becoming silent and introspective. Today, we mostly read in silence, reflecting a modern individualism that seeks a moment of intimacy. But Zapata, as always, offers another perspective, confessing, “When no one was watching, I read aloud.”

The book concludes with the essay “Ways to Disappear,” the chapter from which the book’s title, Empty Pool (Alberca vacía), originates. In it, she reflects on pools that, when empty, can signify abandonment, become art installations, serve as skate parks, transform into gardens, or become sites of terrible events—or magical places where only the innocence of children can see things invisible to adults, as in the poem from Principia by Elisa Díaz Castelo. Zapata recounts her own pools, the ones that have accompanied her over the years, as well as the stories and people in her life intertwined with them. “There were other pools in my childhood.”

A glimpse into the essays Zapata writes in Empty Pool is just a brief look at the themes, names, and references she mentions, and at the many paths she takes to guide us through the cultural history of the world and her own. She explores the things we have and the ways their absence transforms us even more. “We are transformed by things that vanish.”

Today, I invite you to read Isabel Zapata, a powerful voice among the contemporary essayists of Latin America, to let yourself be transformed by the meticulous and delicate way she weaves words, bringing us back to that place inhabited by literature where we, as readers, are invited to stay awhile.

Adriana Pacheco, PhD. es investigadora y es escritora. Fundadora del Proyecto Escritoras Mexicanas Contemporáneas y la fundadora y conductora de la página web y podcast Hablemos, Escritoras. Es coordinadora de los libros Romper con la palabra, violencia y género en la obra de escritoras mexicanas contemporáneas y Rompiendo de otras maneras, cineastas, periodistas, dramaturgas y performers. Es investigadora afiliada de LLILAS, University of Texas, Austin, miembro de Advisory Board del Texas Book Festival y fue miembro y chair del International Board of Advisors en la Universidad de Texas, Austin. Su Twiter es @adrianaXIX_XXI

Adriana Pacheco, PhD. es investigadora y es escritora. Fundadora del Proyecto Escritoras Mexicanas Contemporáneas y la fundadora y conductora de la página web y podcast Hablemos, Escritoras. Es coordinadora de los libros Romper con la palabra, violencia y género en la obra de escritoras mexicanas contemporáneas y Rompiendo de otras maneras, cineastas, periodistas, dramaturgas y performers. Es investigadora afiliada de LLILAS, University of Texas, Austin, miembro de Advisory Board del Texas Book Festival y fue miembro y chair del International Board of Advisors en la Universidad de Texas, Austin. Su Twiter es @adrianaXIX_XXI

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

En una sencilla búsqueda en internet sobre la tradición ensayística Latinoamérica, los nombres que saltan en la mayoría de los resultados integran una larga lista que va desde José Martí, Andrés Bello, Octavio Paz pasando por Alfonso Reyes, Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, Lezama Lima y el imprescindible Carlos Monsiváis. Todos ellos hombres.

Otro es el panorama cuando a la búsqueda se le agrega la palabra escritoras o mujeres ensayistas entonces sí, ahí los resultados arrojan finalmente algunos nombres, no muchos y repitiendo siempre los mismos, mencionados brevemente y sin profundizar. ChatGPT se muestra un poco más creativo y responde a las palabras claves “nombres de ensayistas latinoamericanas” con una lista de diez donde incluye a Silvia Molloy, Marta Traba y Victoria Ocampo, entre otras, repitiendo por supuesto nombres que son los que siempre resultan.

Buscar en internet y ahora en ChatGPT es aprender sobre los enormes huecos oscuros y sesgos que prevalecen en el conocimiento sobre el género literario del ensayo. Muestra, en primer lugar, el vacío que aún vivimos en reconocer y ubicar escritoras que han aportado enormemente al campo. En segundo, se observa la necesidad de biologizar a la literatura, es decir, tener que preguntar específicamente por el género para poder obtener resultados en donde las escritoras aparezcan, lo que no tendría por qué ser necesario cuando hablando de literatura. En tercero, está la falta de un mapeo que permita reconocer nombres actuales y los distintos países del mundo desde donde están escribiendo.

Nombres como Soledad Acosta de Samper, Clorinda Matto de Turner, Victoria Ocampo, Rosario Castellanos, Beatriz Sarlo, las imperdibles Margo Glantz y Angelina Muñiz-Huberman o la muchas que vienen del Caribe y que se nombran en libros como Mujeres ensayistas del Caribe Hispano: Hilvanando el silencio (2007), son tan solo un asomo a una genealogía de grandes ensayistas que inspiran a otras contemporáneas como Irene Vallejo, Betina González, Sonia Cristoff, Verónica Gerber, Jazmina Barrera, Vivian Abenshushan y por supuesto Isabel Zapata.

Y es sobre esta última, Isabel Zapata, de quien quiero escribir hoy en mi intromisión en la conversación sobre literatura contemporánea. Mi pretexto es la reedición que Hablemos, escritoras y Literal Publishing, editorial fundada en Houston Texas y que celebra este año su 20 aniversario, hace de una joya del ensayo contemporáneo: Empty Pool. La reedición, ahora solo en inglés de un libro publicado como bilingüe en 2019 por Editorial Argonáutica con el título Alberca vacía, es en la traducción de Robin Myers, quien ya ha traducido otros libros de Zapata como In Vitro (Coffee House Press) y Una ballena es un país, A Whale is a Country (Editorial Fonógrafo, 2024).

Tal y cómo me ha sucedido con otros libros, lograr que Empty Pool llegara a los Estados Unidos y al mundo anglo en inglés, se convirtió en una obsesión desde el primer momento en que lo leí en 2019, para prepararme para la entrevista que le hice a Zapata. Leerlo me dejó ese sentimiento de empatía y aprendizaje que sus obras siempre dejan como sucede ahora también con su primera novela Troika (Almadia,2024).

El libro, además de incrementar el acervo literario en traducción de obras de gran calidad que vienen de países hispanohablantes, muestra la riqueza de lo que está sucediendo hoy con el ensayo en países como México. Voces como Brenda Ríos, Vivian Abenshushan, Liliana Pedroza, Marina Azahua, Gabriela Jáuregui son ejemplo de la ensayística mexicana contemporánea.

Empty Pool se acompaña además con fotografías con las que la autora se ayuda en el momento de explorar temas como las posibilidades de entablar una conversación con una madre que ya no está, a través de las notas que ésta última deja en los márgenes de sus libros. “Reading the books of my mother means talking to her”. Nos lleva también a un recorrido por escritores notables para demostrar que las maneras de leer empiezan en el momento mismo de ordenar y coleccionar libros en una biblioteca, acto en el que los que amamos los libros mostramos nuestra propia excentricidad y la forma cómo esta cambia a lo largo de nuestras vidas “Library is a collection, and collection means a state of constant construction”.

Se puede tomar este libro también, y de hecho otros de Zapata, como parte de esta escritura en la era del Antropoceno, en donde muchas escritoras están enfocando su mirada en los animales y la naturaleza. La autora regresa al tema como ya lo había hecho desde la poesía en Una ballena es un país, donde dice que la literatura puede construir puentes entre el hombre y la naturaleza a través de la empatía, “to build bridges of empathy in a way that only literature can do”.

Estos ensayos nos llevan ahora a otros animales: a perros, pulpos, pájaros, delfines, chimpancés, elefantes. Al hablar de ellos, Zapata, nos muestra que los humanos nos empeñamos en hablar de lo que vemos, o en las formas en que nos atamos a ellos, o en las maneras cómo ellos nos enseñan una vida sentimental o lo es llorar a nuestros muertos. La historia que se cuenta en el ensayo “A Brief Chronicle of Canine Virtues” es un buen ejemplo, pues revisa hasta dónde puede llegar la fidelidad de los perros, para después hacer un guiño y proponer que se trata, tal vez, de una coincidencia en sus comportamientos totalmente animales y nada humanos, o que hay algo que nos hace idealizar sus acciones. En “In Praise of Nosferatu” aborda que es posible pensar que la inteligencia de un pulpo es cercana a la humana, pero que nuestra pequeñez nunca nos permitirá comprenderlo.

Para mí, que entre más envejezco más me significan la naturaleza y los animales que habitan en ella, los pájaros tienen un lugar especial. Tal vez es su peculiar belleza, sus rituales o por su envidiable libertad de poder verlo todo a la distancia, desde un punto lejano, cenital que me seducen. Es esa fascinación la que hace que encuentre especialmente hermoso el ensayo “Notes on Birds” y lo que Zapata dice sobre que el término que le gusta para nombrarlos. Para ella es el de “ave” y no el de “pájaro”, porque el primero habla de movimiento y en el segundo dan una impresión de quietud. “Ave makes me imagine the animal in the air, while pájaro makes me picture it perched motionless on a branch”

Hoy, que los teléfonos celulares se han convertido en nuestros repositorios de imágenes y en prueba de nuestra moderna obsesión por captúralo todo —yo debo confesar que tengo en mi celular el absurdo número de más de 20,000 fotografías y videos—, el ensayo “Against photography” nos recuerda cuestionamientos de críticos, pensadores y escritores sobre la capacidad de la fotografía para recuperar la memoria. “More than preserving memory, photos replace it”. Zapata revisita la idea de la inocencia de la fotografía en el momento de seleccionar y capturar un instante para mostrarlo tal y como sucedió y proponer que las fotografías arrancan solo una parte de la vida. “There’s something predatory in the act of taking a photo”.

El tema de la traducción es fundamental en la obra de Zapata. Por ejemplo, siempre que habla de las traducciones de sus libros dice que tiene la fortuna de tener a su traductora, Robin Myers, muy cercana a ella, tanto en la manera de ver el lenguaje como en el conocimiento del español de México. Myers, además de ser traductora, es poeta y vivió por largo tiempo en ese país, lo que sin lugar a duda contribuyó ampliamente en su ejercicio como traductora de ésta y de otras escritoras mexicanas como Rosa Beltrán. En Empty Pool, Zapara reserva en el libro una sección para hablar de la traducción haciéndolo desde la ironía, como lo que nos cuenta sobre Nicanor Parra que decidió traducir del ruso —un idioma que no hablaba— al español obra de escritores; o lo que hizo Baudelaire traduciendo a Edgar Alan Poe aunque no dominaba el inglés. Este ensayo es a la vez un reconocimiento a este complejo y delicado arte y de cómo es posible que cree mundos nuevos, como lo que nos dice sobre Ezra Pound, que va mucho más allá que traducir de un idioma a otro. “As a translator, Pound didn’t transform. He created.”

Y así como la traducción puede ampliar nuestra visión del mundo, el ensayo hace lo propio: una vez que lo lees nunca vuelves a ver la vida de la misma manera. Yo, por ejemplo, después de leer Empty Pool, nunca volveré a ver un buffet de comida igual. Será ahora una imagen de nuestra contemporaneidad que nos enfrenta, como todo lo moderno, a la disyuntiva de elegir, a la duda frente a las ilimitadas combinaciones de platillos, a lo absurdo, ambicioso e incluso ridículo que puede ser combinar alimentos que nunca tendrían porque estar juntos. Con este ensayo Zapata dialoga con otras ensayistas que han cuestionado el uso de prácticas, herramientas y objetos contemporáneos que nos hacen seres sociales, tal y como lo hacen escritoras como Margo Glantz con ensayos sobre los zapatos o la cabellera. “I still overcoming my fear of making a fool of myself at a buffet”

Bellísimo el ensayo “Silent Reading” que habla sobre el cambio que a lo largo de los siglos ha sufrido la lectura, yendo de una en voz alta a una silenciosa e introspectiva. Hoy, leemos mayoritariamente en silencio, reflejo de una modernidad individualista que produce un momento de intimidad. Pero Zapata, como siempre, nos enfrenta a otra mirada cuando nos confiesa “When no one was watching, I read aloud”.

El libro cierra con el ensayo “Ways to Disappear”, capítulo de donde viene el título de libro, Alberca vacía, Empty Pool. Ahí hace un recorrido sobre albercas que al estar vacías pueden ser una señal de abandono, una pieza de arte, parques para patinadores, jardines, lugares donde cosas terribles suceden o lugares mágicos en donde solamente la inocencia de los niños puede reconocer cosas que son invisibles para los adultos, como en el poema del libro Principia de Elisa Díaz Castelo. Zapata recorre sus propias albercas, las que la han acompañado por años, así como las historias y personajes de su vida que se entrelazan con ellas. “There were other pools in my childhood”

Esta mirada a algunos de los ensayos que Zapata escribe en Empty Pool es tan solo un asomo a los temas, nombres y referencias que acá ella menciona, a las muchas avenidas que toma para llevarnos a la historia cultural del mundo y a la suya propia, a las cosas que tenemos y la manera en que su ausencia nos transforma aún más. “We are transformed by things that vanish”

Hoy, los invito a leer a Isabel Zapata, una voz estridente entre las poderosas ensayistas contemporáneas de Latinoamérica, para dejarse transformar en la forma en que meticulosa y delicadamente teje las palabras, para regresarnos a ese lugar que la literatura habita y donde nosotros lectores somos invitados a habitar en ella.