A Distant Father*

Mercedes Trigos

Title: A Distant Father

Author: Antonio Skármeta

Publisher House. Other Press

A Distant Father by Antonio Skármeta is a short novel deeply concerned with questions of absence: fragmented relationships, veiled emotions, and conversations marked by the characters’ ephemeral engagement with each other. The novel consists of twenty-five vignettes narrated by a single character—Jacques, the village schoolteacher in the small town of Contulmo, Chile whose poetry translations appear weekly in the nearest city’s newspaper. In the second vignette we learn that the day when Jacques returned from studying at the teacher’s college in the capital was the same day that his father left his mother and the village without offering a clear explanation; “[Jacques] got off the train and [his father] got on, boarding the very same car” (6). Skármeta’s use of language, although praised for its seeming simplicity, is an adequate tool to characterize Jacques as a modest teacher and perhaps not a very good writer, given that the editor of Angol’s newspaper “never rejects [his poems] and never prints them either” (7). The novel is narrated in present tense, which would appear to deviate from the theme of absence, given that it connects the experience of the narrator to that of the reader. However, the present-tense narration also tends to resist and restrict the narrator’s opportunities to offer reflection, further estranging the reader from the main character. Each vignette augments this feeling of alienation, providing only a glimpse of a specific part of Jacques’s day—whatever part he chooses to relate in whatever way he chooses to relate it.

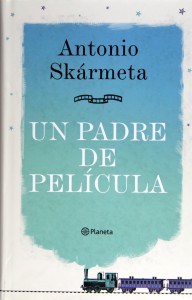

A Distant Father’s original title in Spanish, Un padre de película, carries the connection with the movie theatre in which Jacques finds his father, Pierre, “push[ing] a baby carriage.” It also thematically links the figure of the father to the numerous allusions to cinema in the text—to Westerns, Classics, and some of those genres’ most famous actors. Most importantly, though, the title has the connotation of a father whose actions are so unbelievable, so estranged from reality, that they could only be the subject of movies. The father’s absence, thus, has not been merely physical. Not only does Jacques admit that Pierre was “gone a lot,” but also that the miller “knows more about Dad than [he] does [him]self…more about Dad than [Jacques’s] own mother does” (2, 4). While the narrator is away in college, Pierre cheats on his wife and, without an explanation, chooses to abandon that family in order to take care of an illegitimate son he never publicly acknowledges in Contulmo. Jacques’s struggle making sense of this abandonment, or, as he refers to it, “betrayal,” becomes the main concern of the novel as a coming-of-age text (36).

A Distant Father’s original title in Spanish, Un padre de película, carries the connection with the movie theatre in which Jacques finds his father, Pierre, “push[ing] a baby carriage.” It also thematically links the figure of the father to the numerous allusions to cinema in the text—to Westerns, Classics, and some of those genres’ most famous actors. Most importantly, though, the title has the connotation of a father whose actions are so unbelievable, so estranged from reality, that they could only be the subject of movies. The father’s absence, thus, has not been merely physical. Not only does Jacques admit that Pierre was “gone a lot,” but also that the miller “knows more about Dad than [he] does [him]self…more about Dad than [Jacques’s] own mother does” (2, 4). While the narrator is away in college, Pierre cheats on his wife and, without an explanation, chooses to abandon that family in order to take care of an illegitimate son he never publicly acknowledges in Contulmo. Jacques’s struggle making sense of this abandonment, or, as he refers to it, “betrayal,” becomes the main concern of the novel as a coming-of-age text (36).

One of the moments which has been most striking to reviewers of A Distant Father is when Jacques describes the people of his small, uneventful town Contulmo as “secondary characters, not protagonists” (24). Beyond its immediate appeal as an aid to characterize Jacques as a small-town teacher and translator who perceives himself to be of little to no importance, perhaps this phrase is also remarkable because it echoes the fact that the narrator is not fully developed as a character, and thus could hardly seem a “protagonist.” Some, no doubt, find this characteristic to function in favor of the prominent theme of absence that A Distant Father attempts to convey through a number of lacking and incomplete relationships. They might argue that, as the relationships between characters are detached, so is the relationship between reader and narrator—a type of absent “protagonist.” Others will find that, although Jacques successfully poses for the reader important questions regarding human emotions and motivations, this underdeveloped character fails to engage with these concerns in a meaningful way. What we are left with, then, is a novel that presents some of the questions about human interactions that literature has considered most poignant, but that offers little that truly functions as a guide for us in our search for understanding.

*The novel was translated by John Cullen

Posted: October 16, 2014 at 5:03 am