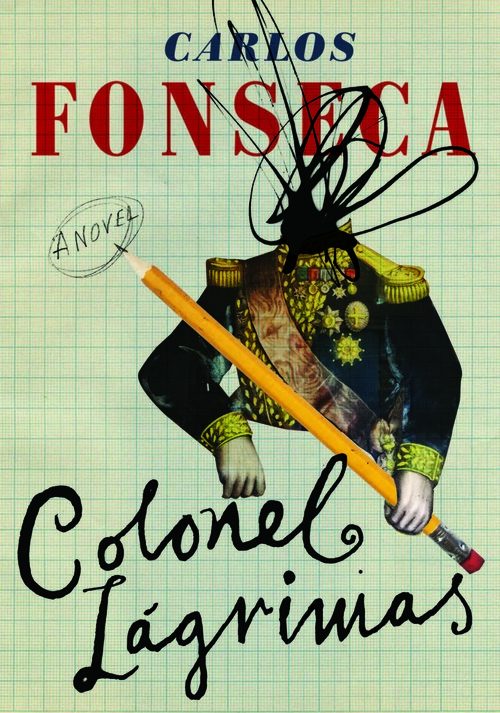

Colonel Lágrimas

Carlos Fonseca

Translated by Megan McDowell

The colonel aspires to have a thousand faces. The file endeavors to give him only one. Now that he’s sleeping we can remove the folder from the cabinet where it is stored, remove the blue band that protects the file, and thumb through it at our leisure, study the case history hidden behind this tired man’s dreams. A heavy folder, grayish in color, on whose first page we find a demand of identity: a name, date of birth, and place of origin. Strange inflexibility for a man who dedicated his life to being many, to seeking happiness through a schizophrenic multiplicity of personalities. The colonel inhabits his century with the anonymity of a fish in water. And nonetheless, a name and a date bring continuity to the archive. Clearly: the sleeping man is only one. We are left with the magic of perspective: to look at him from a thousand different angles, draw a kind of cubist portrait of this tired man. At times, asleep though he is, it would seem that the colonel was posing for us: he turns to one side, he turns to the other, he changes positions as frequently as he changes dreams. We tell ourselves: we must look at the file with the flexible gaze of one who catalogues dreams, we must analyze the colonel’s masks from the elusive position of happiness.

***

In the midst of war, shouldering the pressure of his inheritance, the little colonel learned to play with his masks. In the file we find, in almost indecipherable calligraphy, a note that establishes the precise moment of what would be one of the great realizations of his life: to don a mask was to refuse a destiny. Dated in 1943 and signed by a certain Jacques Truffaut—psychoanalyst at a Parisian orphanage—the note is summarized in the following lines: “The boy refuses to answer in his mother tongue. He rejects Russian with an alarming rage: he seems to want to annul his origins. On the other hand, he embraces Spanish with an angelic fluency.” Truffaut knows little of those rainy evenings in Chalco. Mexico calls up for him ideas of erotic barbarism, of adventure and expeditions with no return, and so he chooses to write—under the heading of birthplace—the French name, Mexique, in an attempt to feel at home. But the little colonel doesn’t like houses, he prefers that theory he discovers in a French copy of National Geographic, in an article about the tribal use of masks in Northeastern Africa. He prefers to think that civilization originated with the mask, the imposed identity, anonymity with a face, endless flux. He thumbs anxiously, happily, through the article that tells of a certain Johan Kaspar Lavater, father of physiognomy, who thought he had discovered the moral outlines of the various personalities in people’s faces. He sketches precise and fantastic drawings in which different faces are juxtaposed with animal physiognomies: a man with a pointed snout compared to a long-nosed dog, a man with a small nose by a buffalo. He laughs in the midst of war, and his laughter is the first of many masks. Years later, the colonel will find in his love of butterflies a kind of final mask, a homeopathic remedy for this, his solitude of large and dramatic laughter.

***

What’s this all about? I suppose it’s about watching him sleep, keeping him company for a while, taking a closer look at him now that he’s asleep. It’s about sketching a face, drawing the features as if this were a forensic study. Now that he’s sleeping, we mobilize a forensic team to examine the scene of the crime. But, of what crime is the colonel accused? Perhaps the transgression of having lived many lives when only one was given him, perhaps the sin of holding on to a secret in the middle of the day. When all is said and done: we might say that he is accused of war crimes. This is about picking up that file and feeling its weight, about opening it and exposing it to the public: the photographs, the psychoanalytic notes, the fingerprints, the letters. A kind of biographical indiscretion that attempts to take stock of a life that contained many lives, making a nuisance of ourselves by rummaging through drawers with the anachronistic goal of sketching a moral outline of this man for whom time is running out. It’s about, as Zenon well knew, realizing the true length of a day: between two almost contiguous points is interposed a life like a knot, and our duty is to unravel it until it is extinguished.

***

His solitude is, however, one that he has come to terms with: this colonel does have one who writes to him. Now that we think about it, we remember him looking at a deep fruit basket overflowing with envelopes—some opened, some not—in a kind of melancholy communion with an outside world: the world beyond these light mountains. Yes: the letters make up more than half of our dear anchorite’s file. When the world thought his isolation was absolute, when it was thought that his final public word had already been uttered, the colonel decided to reconcile himself with the world by means of a simple letter. The card, with its landscape of snow-covered mountains and taciturn horses, with his thin calligraphy, inside of which he merely intimated the intention of a project:

“More letters to come, outlining the project.

For the moment I propose a title: Les Vertiges du Siècle.”

Greetings from,

The Coronel”

Maximiliano Cienfuegos didn’t know what to do when he received the card: his face, perturbed, seemed to become a dynamic nest of contortions. He thought the postcard was a joke in poor taste, a prank his colleagues were playing on him, a jocular welcome to the old fogey club. He even reached the point where he thought it was the late but always predicted arrival of his own imminent insanity. Once resigned to his early old age, he gave himself over to the game, he searched among the fossils of his forgotten French for words capable of translating that letter and that title. He found only a gamut of possibilities that ranged from his favorite, Vestiges of the Century, to the less enigmatic but more reliable Vertigos of the Century. He found, in among some forgotten drawers, a postcard to send in return: the ruins of Teotihuacán at midday. He tried out many responses before confining himself to the frugality that later would strike him as particularly Mexican:

“Delighted to participate in this project. The title—Vértigos of the Century—is perfect.

Greetings from,

Maximiliano Cienfuegos”

The postcard is dated: April 15th, 1981. Twenty-five years later, among the piles of papers, we find the correspondence in its exorbitant totality, astute and absurd, blueprint of the colonel’s architectonic insanity. We place it on a scale and merely say: it weighs ten pounds.

***

It’s the first time we see his signature, the first time we see him name himself: in the closing of the old mathematician’s letter he gives himself a military name. Joke, or madness? Difficult to say. The colonel guards the secret of his name as furiously as he keeps the secret of his origin. What we do know is that at the beginning of the decade, this already bald and tired man decided to leave behind his prolific past in order to embark on a project whose purpose hides behind a title: Vertigos of the Century. Vertigo is what Maximiliano must have felt when he received the second mailing: a kind of incomprehensible package in which the mathematician lost his senses and threw himself into a series of strange historical phenomena. Vertigo and apprehension is what Maximiliano must have felt upon seeing the madness of that great mathematician cum colonel. Vertigo, anxiety and happiness is what Maximiliano Cienfuegos must have felt when he saw that his idol had chosen precisely him—with whom he had exchanged scarcely a few words, a game of chess, in a colonial hotel in Mérida—to design the start of that childish ambush of the real. Unable to communicate his happiness, fearful of losing it, he merely stowed away his terrible joy in the same drawer where he kept the letters. From the Pyrenees, a newly designated colonel was smiling at him without teeth, in this, his infantile return to his Mexican days.

***

Maximiliano always wondered why he had been the chosen one. Seeing that we’re dealing here with a game of names and titles, we will hazard an answer: perhaps the colonel believed he heard aristocratic echoes in Maximiliano’s name, the irony of a name that played with a history, now almost forgotten, of impossible emperors and transatlantic projects. Perhaps, in his old infancy, the colonel remembered his mother’s voice in the middle of the disjointed Mexican landscape, the happiness before the wars, the Aztec peace of a friendly face that looked at him with admiration in the middle of a plaza flooded with red. Perhaps then, with that face in his mind mingling with his mother’s voice, the colonel conjured a name and an address the way one conjures up a fate. The truth is that without knowing why, Cienfuegos took on his new role of confidante with the rigor of the prophet who knows himself to be part of a plan, though he does not know its aim. Maximiliano, the first prophet. Maximiliano, the last apostle. Only his task was not to lay the first stone of a church, but to take part in a project that at every step seemed more mad and absurd, with the stubborn conviction that his colonel would be his guide through the desert toward tropical zones. The blind faith of this apostle is depicted in the letters that carry his name.

***

Eventually, the gambler gets tired and decides to bet everything on one number: he bets definitively, fortuitously. Our Mexican friend must have felt something like that when he received a photo of his old idol along with the first letters. He had played his last card on a tired old man of whom not even the prestige of a name remained. He had bet everything on a man who was no longer what he had been. And nonetheless, it is only from this perspective that we can understand the crazy inertia with which he gave himself over to the ludicrous project. In just the first five years, we find over a hundred letters overflowing with symbols, with half-finished sketches of theories, scribbles in the margins, playful doodles. A quick look and we can discern that in these first years, the letters of Vertigos of the Century seem to obey the absurd logic of four arbitrary categories:

Climates

Dreams

Spinning tops

Rope

Almanac of postcards, a glossary of gibberish, Vertigos of the Century is the masterpiece of a tired genius. Yes: that man who is now sleeping, that man who has now started to snore with the force of an exhausted buffalo, has more than one reason to be tired. With the strength of a child who, as soon as he learns to speak, babbles his own private language, our colonel devotes himself to outlining the categories of an age. Among the ins and outs of these categories, Maximiliano’s misfortunes fade away.

***

Maximiliano Cienfuegos: the name carries the history of another Maximilian’s misfortunes, Maximilian of Hapsburg, over whose name Mexico drew the final red sword of the monarchy. That other Maximilian, under whose countenance Napoleon III imagined a conquered America, a monarchical America, an America that ended up answering him with the quiet force of three gunshots. The Second Mexican Empire and the misfortunes of its unhappy emperor are depicted under the entry that the colonel has dedicated to Amalia de Portugal:

Amalia de Portugal (1831-1854): daughter of emperor Pedro I of Brazil, Amalia takes her place in history as the first and only princess of Brazil. Her premature death left the man who was to be her future spouse in mourning: Fernando Maximiliano José María de Habsburgo (or Maximilian I). The story of this unfortunate aristocrat is of particular interest. The Archduke of Austria whom Napoleon III named as the new emperor of Mexico, Ferdinand Maximilian thus becomes Maximilian of Mexico, the Second Emperor, as part of an attempt to insert an anachronistic monarchy into the cartography of the recently formed Latin American republics. His death is especially interesting: in a trial in the Iturbide Theater presided over by a colonel and six captains, he was condemned to death. The sentence was carried out on June 19th, 1867: Amid shouts of “Viva México!” fell on his back, his torso riddle with bullet holes, while two of his generals stood beside him. Among his final belongings was found a ring holding a lock hair belonging to his lost love: Amalia.

A colonel, perhaps out of jealousy, sentenced this romantic Maximilian of Mexico to the firing squad. Another colonel, a century later, would condemn another Maximiliano to a similar fate. Just like his predecessor, our Maximiliano lost everything but the dignified arabesques of his name: he lost his wife, custody of his two small children, his professorship, all so he could follow in the footsteps of a man without a future,upon whom the past weighed too heavily. Maximiliano Cienfuegos, imitating his imperial ancestor, bet blindly on a number that wasn’t even on the board.

*An excerpt of Colonel Lágrimas by Carlos Fonseca. Translation forthcoming this autumn from Restless Books

Posted: September 8, 2016 at 10:00 pm