Constructing Abstraction with Wood: Joaquín Torres-García

Cecilia de Torres

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

When the exhibition Joaquín Torres-García: Constructing Abstraction with Wood opens on September 25th at The Menil in Houston, it will be the museum’s first individual show dedicated to a Latin American artist. The exhibition concentrates in his constructions, figures, and toys, made of wood.

Joaquín Torres-García was born in Uruguay of Spanish parents; during his peripatetic life he lived in Barcelona, New York, Italy, Paris, Madrid, and after 43 years abroad he returned to his country. In Montevideo, he devoted the last years of his life to create an art movement and a studio workshop from which artists of international stature emerged. His art concepts were rooted in Europe’s cultural traditions as well as in the America’s; this broader perspective and universal viewpoint were an important reference for future generations of artists.

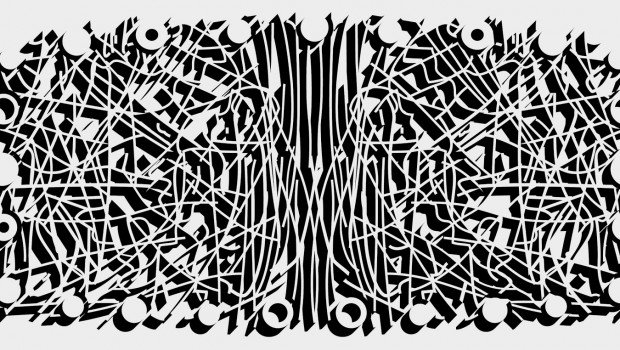

In past exhibitions of Torres-García’s work, the emphasis was on his paintings, until a survey of his toys in Spain in 1997, titled Aladdin Toys enjoyed great success while it changed the perception that they were a mere diversion, secondary to the important core of his artistic production. Constructing Abstraction with Wood challenges the paintings relevance over the wood constructions. The exhibition demonstrates that in fact they represent a new direction in his research bringing the three dimensional realm into his painting. They are a very personal interpretation of the idiom of relief and pure abstract form. On one hand they relate by their rough look and in some cases an animistic aura to primitive art, but they also embody the geometric and constructivist idiom, that characterizes Torres-García’s dilemma: his reluctance to let go of the art of the past for a total embrace of the present.

Torres-García’s attraction to wood as a material started in his childhood. His Spanish father had immigrated to Montevideo driven like so many of his countrymen, to make a fortune in America. He opened a general store in the outskirts of Montevideo, where the gauchos from the countryside came to buy supplies and sell their products. The store had a large warehouse, stables, a bar, and a carpentry shop, where Torres-García fi rst experimented with constructing in wood. He also enjoyed opening and assembling the boxes of imported goods, such as sewing machines, furniture, and tractors. In spite of Uruguay’s obligatory school education, the young lad regularly ran away prefering to study at home by himself. When he was 17 in 1891, his father decided to return to Spain, to Mataró his native small town near Barcelona where Torres-García learned basic drawing and painting techniques in the local school. The next year they settled in Barcelona, which at the turn of the Century was the most cosmopolitan town in Spain.

There Torres-García studied art in the academies, and frequented the famous cafe Els Quatre Gats where young and talented artists like Julio González and Pablo Picasso gathered. In those days they were inspired by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Parisian life scenes. But Torres-García was drawn to Greek philosophy and when he learned of the French artist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes pastoral paintings, he embraced Classicism as the expression of a higher artistic model. He became well known and recognized as the artist who best represented Catalan national spirit within the Mediterranean tradition, which got him an important commission to decorate with large murals the main hall in the Government Palace in Barcelona.

He met his future wife Manolita Piña when he was hired to be her private drawing tutor; in 1910 they married. They had four children they gave Greek and Roman names: Olimpia, Augusto, Iphigenia and Horacio. Torres-García observed them at play, and seeing that they broke their toys to learn how they functioned, he realized that they didn’t answer the child’s need to learn playing. He designed toys in parts that could be interchanged and became so involved with their creative and didactic possibilities that he teamed with a carpenter to produce toys which he called “art toys,” and created the Alladin Company. In 1917 he abandoned the Classically inspired style for contemporary and dynamic paintings inspired by modern urban life and in 1920, he moved to New York the most modern of all cities.

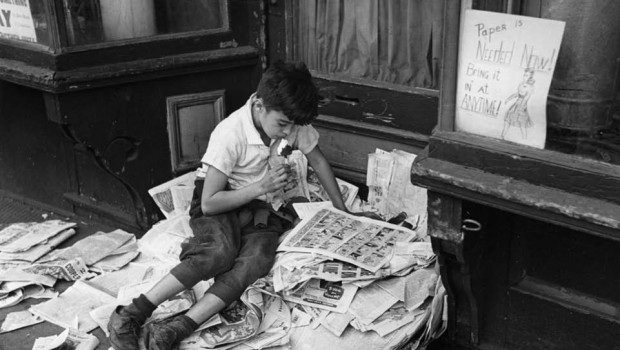

He was powerfully impacted by its raw energy, its non-stop motion, its imposing architecture, and by its popular culture: advertising art, cartoons, and the movies. He only stayed for two years, but they were determinant because in New York, Torres-García was able to break with the past and consolidate new ideas for future developments. His crowded New York paintings capture the multifaceted aspects of city life; they display the American flag, clocks, buildings, trains, brand product names, the frantic traffic, billboards, and crowds. From New York he returned to Europe in 1922 spending some time in Italy and the South of France, in 1926 he finally settled in Paris, at that time the art center of the world and where he had always yearned to be.

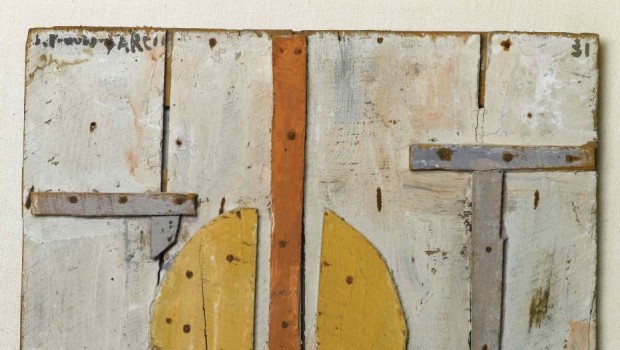

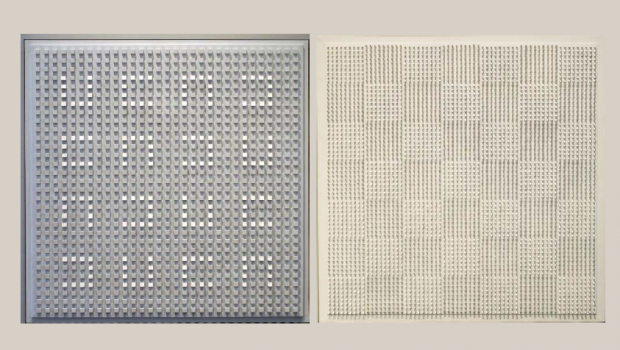

The majority of the wood constructions in The Menil exhibition, which Torres-García called plastic objects, were made in Paris between 1927 and 1932. They are precariously assembled from humble materials: found wood haphazardly put together with nails, they are sometimes painted over the unfinished rough texture, or are carved or incised. Guest curator Mari Carmen Ramírez, the Wortharm Curator of Latin American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, wrote they are “unclassifiable objects,” and stresses that “the emphasis on the economy of means and the insertion of extra pictorial values merges with several well-known poetics: Cubism’s analytical and synthetic deconstruction of representation; Dada’s iconoclastic use of recycled materials; Neo-Plasticism’s grid-based metaphysical insights; Surrealism’s heaping of bizarre intuitions; and Primitive art, understood as an animistic perception of a natural world with no tradition.”

In Paris Torres-García was finally able dedicate all his energy to painting and writing. He met key pioneers of the avant-garde like Piet Mondrian, Jean Arp, and Theo Van Doesburg, and exhibited his work in important art galleries. During this period he wrote introspective texts in search of his own artistic personality. About originality, he wrote to himself: “Walk with faith. Because despite the importance of discovery in art, of the new theory, of the invention, something more important makes the work: that which is really ours and unique to us. That which is really unprecedented [l’inédit] or nonexistent before us.”

Some of Torres-García’s wood constructions of masks and figures were inspired after seeing the ancient arts of the Americas in New York’s Museum of Natural History and in Paris’ Musée d’Antropologie in 1928. These primitive-wood figures and assamblages challenge the prevailing aesthetic models of the 1920s that copied industrial production finishes. By favoring a hand-made look and borrowing the constructive systems in primitive art, Torres-García was going against the trend in modern art towards a total break with the past. The pictorial quality of his paintings, his preference for grays and earth pigments, which are the trademark of his work, makes them still unclassifiable. In the context of The Menil’s superb collections of African and Oceanic art, Torres-García’s objects will show continuity with mankind’s diverse art works throughout the ages.

Soon after arriving in South America in 1934, Torres-García made a drawing of the map of the continent up-side down. This radical image illustrates how important it was for him to establish his place in the world. His ambition was to create with the students of his workshop an independent art movement in Uruguay which he hoped to export to the rest of the Americas. By stating that the South was from now on his North, he was challenging the supremacy of European culture at the time in peril due to the second world war.

The South because it is our North. We place the map upside down, then we have the right idea of our hemisphere, not the way they want it on the other side of the world. The tip of America points insistently South, which is our North. The same with our compass: it leans irremissibly always South towards our Pole. When ships leave from here going North, they go down not up as they used to. Because North is now under, and Levant is to or left.

In South America he embarked in a project to study and validate the cultural heritage of the Americas. In the exhibition his last work of wood made in 1944 and titled “Monument,” is included. With roughly cut blocks of lapacho a local hardwood, he built a wall like construction inspired by the tectonic quality of the great stone walls in Cuzco, Peru. In one block he inscribed the sun, a reference to Inti the father god in the Inca trilogy, and a triangle. In other blocks the words abstract and concrete. This impressive construction unites two apparently incompatible worlds: the modern and the ancient, with references to the great civilizations he most admired; the classical Greek and the Inca Tiwanaku. In the large self standing piece, Torres-García underscores what is timeless and common to all great art: structure, abstraction, and faith in the religious essence of art.

Posted: April 18, 2012 at 10:18 pm