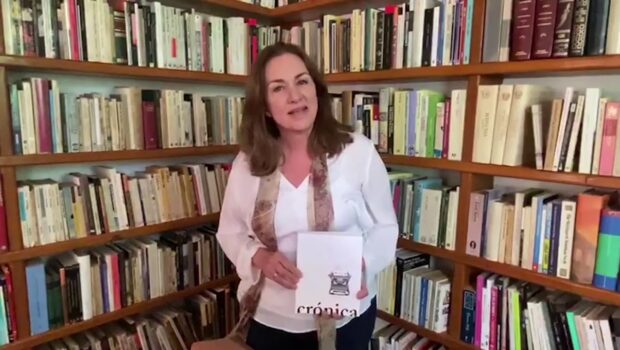

Barcelona Chronicle

Crónica de Barcelona

Maarten van Delden

In the ample, sun-splashed courtyard of the Jaume I building at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, vast banners proclaim the students’ support for Catalan Independence. “Hem votat la república,” they declare. “We have voted for the Republic.” On October 1st, 2017, the Catalans voted overwhelmingly in favor of seceding from Spain, although turn-out was only around 43% of eligible voters. The Spanish newspapers rarely refer to the October 1st referendum—widely known as the “1-O”—without attaching the adjective “illegal” to it, which is what Spain’s Constitutional Court had declared it to be. The students at the Pompeu Fabra are not concerned with such niceties. For them, the vote was a clear expression of the will of the people.

My conference is on the Hispanic essay. On the first day—Wednesday, October 25th—the panels and round-tables proceed smoothly—in Castilian. I try to detect references to current events, but fail to notice any. In the call for papers, the organizers had stressed their interest in connections, flows and networks. There is much talk in the panels I attend of journals, translations, publishing houses and exchanges of letters between prominent intellectuals. In the world that emerges before my eyes as I listen to the speakers, everyone seems to be conversing with everyone else, across boundaries. I see lines being drawn across the Atlantic, from Spain to Paris, Puerto Rico to New York, Brazil to California.

The organizers have provided ample time for lunch—two-and-a-half hours, from 2 to 4:30 pm. After the last morning panel, I walk back to my hotel on the calle Caspe. There is little traffic in the streets, enveloped in the warm glow of the afternoon sunshine. Two traffic policemen examine the location of a small white van parked on a street corner a few blocks from the Pompeu Fabra, and then start writing out a ticket. They do everything in a calm, deliberate manner. Near the bus station, young travelers crisscross the esplanade with their suitcases on wheels rattling behind them. I have lunch in my hotel, and then return to my room for a nap. Jet-lagged, I don’t make it back to the conference for the afternoon sessions.

Late in the evening I have dinner at the Xampú Xampany restaurant, near the plaza Tetuán. I find a table in the restaurant’s small sidewalk section. María Luisa, the Filipina waitress, who remembers me from previous visits, stops to make some small talk as she goes about attending to her customers. At one of the nearby tables, five prosperous-looking women in their twenties and thirties are drinking, smoking and talking loudly, switching almost unnoticeably between Castilian and Catalan. I can hear them enumerate the various places in Spain from which their forebears migrated to Catalonia. Cádiz, Cuenca, Sevilla, Extremadura… María Luisa tells me that there have been many demonstrations in the city in recent months, and fewer tourists. In the mornings she goes to class, and in the evenings she works at the restaurant. She wants to become a pharmacist. I learn that she has relatives in Southern California.

On Thursday afternoon, I present my paper at the conference. I talk about Octavio Paz’s views of the colonial period in Mexican history, and of the Mexican struggle for independence from Spain. The campus of the Pompeu Fabra is across the street from the Catalan parliament, where around the same time as my paper presentation, lawmakers have gathered to discuss the threats from Spain’s central government to suspend the region’s autonomy. There are rumors that Carles Puigdemont, the Catalan president, will declare independence. Or perhaps he will call early elections… In the end, nothing happens, and a new session is called for Friday afternoon.

After my paper presentation, I have a drink in a nearby café with Aurelio Major, the Canadian-Mexican editor of Granta en español. Major was close to Paz in the 1990s and over a beer he shares some reminiscences of that period of his life. After a while, the conversation turns to the Catalan situation. Some independentistas, he says, want the Spanish government to invade Cataluña; they believe there would be no better way to generate international sympathy for their cause. A few days later, I read a similar analysis in one of the Spanish papers. The secessionists in Cataluña long for their Tiananmen Square moment, the author says.

On Friday the 27th, I arrive at the Pompeu Fabra around 11 am. A helicopter is hovering ominously overhead. I can’t locate it in the sky, but I can hear its monotonous droning. In the lobby of the building where the next conference panel will take place, I run into several elderly women sporting Catalan flags as if they were Superman capes. One of the women, looking agitated, asks for directions to the bathroom.

Imagen de Adolfo Luján

I have lunch again at my hotel. Suddenly, there is honking in the streets, but the noise dies down almost immediately. The two young women at the table next to mine check their phones. “Pues ya está…” one of them says. “So it’s done…” They look at each other in silence. I decide to check my phone, too. El País has a headline up announcing the Catalan parliament’s unilateral declaration of independence. I ask for the check, and look at some more web-sites. El Mundo compares the independence supporters who have gathered outside the Ciutadella park to soccer fans. Apparently, a large screen had been put up on which the crowd followed what was happening inside the parliament building. Cheers had gone up with every “yes” vote. The reporter notes snidely that it was as if they were celebrating a goal at a Champions League game.

I take a taxi back to the conference site. My driver—a young man—is noncommittal in response to my questions. I don’t much follow politics, he says. We don’t know yet whether this will have an effect on tourism. Everything will depend on how the Spanish government responds.

I arrive at the Pompeu Fabra around six-thirty in the evening for the closing plenary lecture by the Spanish writer and diplomat José María Ridao. It appears, however, that the afternoon sessions are running behind schedule, and as a result Ridao’s talk will begin around forty-five minutes to an hour late. I stand around with a few other conference goers, and no one talks about what has happened in Barcelona a few hours earlier. One participant who is originally from Barcelona but now teaches at a university in the United States sports a button on his lapel with the image of a rosy-looking baby. The words “mommy, I’m afraid of the government” circle the baby’s head. I refrain from asking the wearer of the button which government he’s afraid of.

Ridao begins his talk by referring to how “conmovido,” shaken, he feels by the afternoon’s events. “Es muy triste,” he says. “It’s very sad.” It is the first time I hear someone at the conference offer an explicit opinion on the political conflict racking the country. But Ridao does not delve further into the question of Catalan independence. Still, in his talk, which has been billed as a discussion of the readings that influenced him as his literary career developed, he adopts a decidedly anti-nationalist stance. He complains that Ortega y Gasset worried too much about questions of identity, and he states that among Octavio Paz’s books he prefers El ogro filantrópico over El laberinto de la soledad. Ridao is in his mid fifties, but he looks much younger. He speaks well, and he has an agreeable manner. After the talk ends, I walk to the street with a colleague from Barcelona who had presented on the same panel as me the day before. We complain about how cold it was in the room where Ridao delivered his lecture.

Back in my hotel, I quickly check the news. Within hours of the Catalan unilateral declaration of independence, the central government, invoking article 155 of the constitution, has suspended Catalonia’s autonomy, removed Puigdemont and his cabinet from office, dissolved the regional parliament, and called for new elections to be held in Catalonia on December 21st.

The neighborhood where I’m staying is full of Chinese-run businesses: hair salons, cafés and massage parlors. On Friday evening, my conference over, I decide to get a hair-cut in a modest, clean and brightly-lit salon one block from my hotel. Opening hours are until nine-thirty in the evening. A young woman with a bright expression on her face cuts my hair. I ask her what part of China she’s from. Her Spanish is excellent. I’ve lived here for ten years, she says. I like to learn languages. Then I ask her what she thinks of today’s declaration of independence. For us, she says, hesitating briefly, it makes no difference.

After my hair-cut, I wander around the city streets. The atmosphere is strangely subdued. The helicopter is still hovering ahead, emitting its menacing, seemingly interminable growl. I have a bite to eat at a sidewalk café on the Passeig de Sant Joan, only a few blocks from where the day’s momentous events took place. I witness no dancing in the streets, nor loud revelry of any kind. Only a few stragglers with their Catalan flags draped over their shoulders. I ask my server—who tells me that she is from Morocco—what she thinks of today’s events. She stands a little closer, and adopts a confidential tone. “This is a very beautiful city,” she says, “and they’re going to ruin it with their idiocy.” I ask her about the helicopter. “La policía nacional,” she explains. “And what do you think is going to happen next?” She places one wrist over another, as if she has been hand-cuffed. “Todos a la cárcel,” she says with a glint in her eyes. “They all go to jail.”

In the morning, I look at some news reports. CNN states that the Catalan parliament voted “overwhelmingly” to proclaim the region’s independence. There is no mention of the fact that fifty-five lawmakers walked out of yesterday’s parliamentary session, not wanting to participate in what they regarded as an illegal vote. Out of the eighty deputies who participated in the vote, seventy cast a “yes” ballot. That makes seventy out of a total of one hundred and thirty-five. The Washington Post runs a piece hinting at sympathy for the secessionists, but with a strange mishmash of left-wing and right-wing perspectives. First, there’s a quote from a left-wing columnist, who equates the Catalan fight for independence with the struggle for democracy in the face of an oppressive state. Next, we hear from a right-wing columnist who sees the Catalans as rightly not wanting to share their wealth with their poorer neighbors in other parts of Spain. The Catalans, he says, feel “shackled to a corpse.” I wonder how a madrileño or a sevillana, or anyone from anywhere else in Spain, for that matter, would feel if they read that…

After spending the morning reading, I go out around noon. The day is cloudy and there’s a slight chill in the air. The city is beginning to look autumnal, wrapped in a greyish light, the tired-looking leaves of the plane trees that line its avenues waiting to drop gently to the ground. I eat a sandwich at an outdoor café on the calle de la Marina. The passersby are a mix of moderately well-dressed locals and tourists returning from a visit to the Sagrada Familia cathedral, only a few blocks up the street. After finishing my lunch, I walk along the Gran Via in the direction of the Rambla de Catalunya. At the Casa del Libro, I purchase two books: Alberto Fuguet’s Sudor and a collection of essays on Albert Camus by José María Ridao, yesterday’s speaker. There are plenty of the usual fashionably-dressed shoppers strolling along the city streets in this part of town. The sun has come out and a cool breeze is blowing. I head down to the Plaça de Sant Jaume, and find the square packed with reporters and camera crews. I take pictures of the ajuntament and the Palau de la Generalitat. To my surprise, I see that the Spanish flag is still flying over the government buildings.

There is a sudden tumult in the square. A man in his sixties, overweight, pushing a sports bike, and wearing a tight red-and-black cycling outfit, is shouting something at the policemen guarding the entrance to the Generalitat. He walks with his bike towards the middle of the square, where a reporter asks him a few questions. I approach to listen. The man is angry. “¡Esto es España!” he shouts, as he chops the air with his right arm. “This is Spain!” He points at the ground. “¡Yo estoy en España!” he declares. “I’m in Spain!” The reporter asks him a question that I can’t hear. He is describing the leaders of the secessionist movement as “liars” and “phonies.” Everyone, he shouts, should go back to work on Monday. “¡A trabajar!” he exclaims, glaring at the crowd that has gathered to listen to him.

In a different part of the square, a smiling, middle-aged woman is talking to another reporter. “They will never let us go,” she says, almost cheerfully, referring to the rest of the country. “Somos lo mejor de España,” she adds. “We are the best part of Spain.” She looks very pleased with her analysis. “Somos la coca,” she concludes. “We’re the crème de la crème.” The reporter thanks the lady for her words.

Back in my hotel room, I spend the evening watching the news. A representative for one of the pro-independence parties insists that several countries are on the verge of recognizing Catalonia as an independent nation. Slovenia, Finland, Argentina… the list is not very long. It is reported that Carles Puigdemont has returned to his hometown of Girona, where he is spotted, on Saturday around lunch-time, enjoying a glass of wine in a bar, while he watches himself on television delivering a brief statement rejecting his removal from office by Spain’s central government, and calling on the Catalans to resist the imposition of article 155 of the Spanish constitution, albeit in a peaceful manner.

By Monday, I’m back in Los Angeles. Puigdemont has left Catalonia and is now in Brussels. A friend informs me that Manuel Castells, the eminent Catalan sociologist, is giving a talk on the situation in his homeland at the University of Southern California, where he occupies a prestigious chair. Later, my friend tells me that there had been a confrontation between Castells, who supports independence, and the Spanish consul in Los Angeles, who had attended the talk. According to my friend, Castells had argued that support for independence had increased after the Spanish government’s rough attempt to halt the October 1st referendum. The comment reminds me of what my taxi driver had said on the way to the airport in Barcelona on Sunday. What do you think will happen now? I had asked him. It depends on what the Spanish government does, he had said. If they overreact, they will drive more people into the independentista camp. Castells had also claimed that the latest polls showed that the pro-independence camp would win the upcoming election. When I check the polls myself, Castells’s confidence in the victory of his cause turns out to be unwarranted. The Catalan electorate is closely divided, and the outcome of the election remains extremely difficult to predict.

*Cover image by Sasha Popovic

Maarten Van Delden is the author of Carlos Fuentes, Mexico and Modernity (Vanderbilt University Press, 1998) and–along with Yvon Grenier–coauthor of Gunshots at the Fiesta (Vanderbilt University Press, 2009)

Maarten Van Delden is the author of Carlos Fuentes, Mexico and Modernity (Vanderbilt University Press, 1998) and–along with Yvon Grenier–coauthor of Gunshots at the Fiesta (Vanderbilt University Press, 2009)

©Literal Publishing.

Traducción de Rose Mary Salum

En el amplio y luminoso patio del edificio Jaume I de la Universitat Pompeu Fabra de Barcelona, grandes pancartas proclaman el apoyo de los estudiantes a la independencia catalana. “Hem votat la república“, declaran. “Hemos votado a favor de la República”. El 1 de octubre de 2017, los catalanes votaron abrumadoramente a favor de la separación de España. Sin embargo, la participación solo constó de alrededor del 43% de los ciudadanos con derecho a voto. Los periódicos españoles rara vez se refieren al referéndum del 1 de octubre, ampliamente conocido como el “1-O”, sin agregar el adjetivo “ilegal”, en alusión al dictamen pronunciado por el Tribunal Constitucional de España. A los estudiantes de Pompeu Fabra no les parece preocupar este detalle. Para ellos, el voto fue una clara expresión de la voluntad del pueblo.

He venido a Barcelona para participar en un congreso sobre la modernidad hispánica. El primer día, el miércoles 25 de octubre, los paneles y las mesas redondas se desarrollan en un ambiente tranquilo. Todos los participantes presentan en castellano. Intento identificar referencias a los hechos actuales, pero no las encuentro. En la convocatoria, los organizadores del simposio habían subrayado su interés en que se exploraran las redes y flujos que conectan los distintos puntos del mundo literario hispánico. En los paneles a los que asisto se habla mucho de revistas, traducciones, editoriales e intercambios de cartas entre intelectuales prominentes. Mientras escucho a los oradores, veo surgir ante mis ojos un mundo en el que todos parecen estar conversando con todos, sin importar fronteras. Se trazan líneas que cruzan el Atlántico, que van desde España a París, Puerto Rico a Nueva York, Brasil a California.

Los organizadores dan más que suficiente tiempo para almorzar, dos horas y media, de 2 a 4:30 p.m. Después del último panel de la mañana, regreso caminando a mi hotel en la calle Caspe. Hay poco tráfico en las calles, envueltas por el cálido sol de la tarde. Dos policías examinan la ubicación de una pequeña camioneta blanca estacionada en una esquina a pocas cuadras de la Pompeu Fabra, y luego preparan una multa. Hacen todo de una forma tranquila y metódica. Cerca de la estación de autobuses, grupos de jóvenes viajeros cruzan la explanada con sus maletas con ruedas haciendo un gran traqueteo contra el pavimento. Almuerzo en mi hotel, y luego regreso a mi habitación para tomar una siesta. Ya no vuelvo a la sesión de conferencias de la tarde debido al cansancio provocado por el jet-lag.

Ya tarde en la anoche ceno en el restaurante Xampú Xampany, cerca de la plaza Tetuán. Encuentro una mesa en la pequeña sección de la acera del restaurante. María Luisa, la camarera filipina, que me reconoce de visitas anteriores, se detiene en mi mesa para charlar un poco mientras atiende a sus clientes. En una de las mesas cercanas, cinco jóvenes mujeres que parecen pertenecer a una clase acomodada beben, fuman y hablan ruidosamente, alternando entre el castellano y el catalán casi de forma inadvertida. Puedo escucharlas enumerar los diversos lugares en España desde los cuales sus antepasados emigraron a Cataluña. Cádiz, Cuenca, Sevilla, Extremadura … María Luisa me cuenta que ha habido muchas manifestaciones en la ciudad en los últimos meses y que han llegado menos turistas. Por las mañanas va a clase y por las noches trabaja en el restaurante. Dice que quiere ser farmacéutica. Me entero de que tiene parientes en el sur de California.

El jueves por la tarde, presento mi trabajo en el congreso. Hablo de las opiniones de Octavio Paz sobre el período colonial en la historia de México y de la lucha mexicana por la independencia. El campus de la Pompeu Fabra se ubica muy cerca del parlamento catalán, y al mismo tiempo que yo doy mi presentación, los legisladores se reúnen para discutir las amenazas del gobierno central de España para suspender la autonomía de la región. Hay rumores de que Carles Puigdemont, el presidente catalán, declarará la independencia. O tal vez que convoque a elecciones anticipadamente … Al final, no se toma ninguna decisión y se convoca una nueva sesión para la tarde del viernes.

Después de mi presentación voy a tomar una copa en un lugar cerca de la universidad con Aurelio Major, el editor canadiense-mexicano de Granta en español. Major formó parte del círculo de intelectuales en torno a Paz en la década de 1990 y mientras disfrutamos de una cerveza comparte algunos recuerdos de ese período de su vida. Después de un rato, la conversación se inclina por la situación catalana. Algunos independentistas, dice, quieren que el gobierno español invada Cataluña; creen que no habría mejor manera de atraer la simpatía de la comunidad internacional por la causa catalana. Unos días más tarde, leo un análisis similar en uno de los periódicos españoles. Los secesionistas en Cataluña anhelan un momento similar al de la Plaza de Tiananmen, dice el autor.

El viernes 27, llego a la Pompeu Fabra alrededor de las 11 a. m. Un helicóptero se cierne ominosamente en el espacio. No puedo ubicarlo en el cielo, pero puedo escuchar su zumbido monótono. En el vestíbulo del edificio donde se realizará el próximo panel del congreso, veo algunas mujeres mayores portando banderas catalanas en la espalda como si fueran capas de supermán. Una de las mujeres, con aspecto agitado, pregunta cómo llegar al baño.

Por la tarde, almuerzo de nuevo en mi hotel. De pronto escucho las bocinas de los autos en las calles, pero el ruido desaparece casi de inmediato. Las dos mujeres jóvenes en la mesa contigua a la mía revisan sus teléfonos. “Pues ya está …” dice una de ellas. Se miran en silencio. Decido revisar mi teléfono también. El País anuncia en la primera página la declaración unilateral de independencia del parlamento catalán. Pido la cuenta y veo algunos sitios web más. El Mundo compara a los proindependentistas que se han reunido fuera del Parc de la Ciutadella con unos fans de fútbol. Aparentemente, se había colocado una gran pantalla en la que la multitud seguía lo que transcurría dentro del edificio del parlamento. Las aclamaciones habían aumentado con cada voto del “sí”. El reportero señala sarcásticamente que era como si estuvieran celebrando un gol en un juego de la Liga de Campeones.

Tomo un taxi de vuelta al sitio del congreso. Mi conductor, un hombre joven, se comporta de manera evasiva frente a mis preguntas. No sigo mucho la política, dice. Todavía no sabemos si esto tendrá un efecto en el turismo. Todo dependerá de cómo responda el gobierno español.

Llego a la Pompeu Fabra alrededor de las seis y media de la tarde para la conferencia magistral de clausura del escritor y diplomático español José María Ridao. Parece, sin embargo, que las sesiones de la tarde se están retrasando y, como resultado, la charla de Ridao comenzará entre 45 minutos y una hora más tarde. Espero junto con algunos otros asistentes a la conferencia, y nadie habla de lo que ha sucedido en Barcelona unas horas antes. Un participante que es originario de Barcelona, pero ahora enseña en una universidad de los Estados Unidos, porta un botón en la solapa con la imagen de un bebé de aspecto rosado. Las palabras “mommy, I’m afraid of the government”, “mami, le temo al gobierno”, rodean la cabeza del bebé. Me abstengo de preguntarle al usuario a cuál de los gobiernos le tiene miedo.

Ridao comienza su charla refiriéndose a lo “conmovido” que se siente por los acontecimientos de la tarde. “Es muy triste”, dice. Es la primera vez que escucho a alguien en el congreso ofrecer una opinión explícita sobre el conflicto político que afecta al país. Pero Ridao no profundiza en la cuestión de la independencia catalana. Aún así, en su charla, que trata de las lecturas que lo influenciaron a lo largo de su carrera literaria, adopta una postura decididamente antinacionalista. Se queja de que Ortega y Gasset se preocupó demasiado por el tema de la identidad y afirma que, entre los libros de Octavio Paz, prefiere El ogro filantrópico a El laberinto de la soledad. Ridao tiene cincuenta y pico de años, pero parece más joven. Habla muy bien y tiene una manera de ser agradable. Después de que termina la charla, camino a la calle con una colega de Barcelona que había presentado en el mismo panel que yo el día anterior. Nos quejamos de lo frío que estaba la sala donde Ridao pronunció su conferencia.

De vuelta en mi hotel, veo rápidamente las noticias. Pocas horas después de la declaración unilateral de independencia de Cataluña, el gobierno central, invocando el artículo 155 de la Constitución, ha suspendido la autonomía de Cataluña y destituido a Puigdemont y su gabinete, además de disolver el parlamento regional y convocar a nuevas elecciones en Cataluña para el 21 de diciembre.

El vecindario donde me alojo está lleno de negocios administrados por chinos: peluquerías, cafeterías y salones de masajes. El viernes por la noche, concluido el congreso, decido cortarme el pelo en un salón modesto, limpio y bien iluminado a una cuadra de mi hotel. El horario de apertura es hasta las nueve y media de la tarde. Una mujer joven con una expresión sonriente me corta el pelo. Le pregunto de qué parte de China es. Su español es excelente. He vivido aquí durante diez años, dice ella. Me gusta aprender idiomas. Luego le pregunto qué opina de la declaración de independencia de hoy. Para nosotros, dice, vacilando brevemente, no hay ninguna diferencia.

Después de mi corte de pelo, deambulo por las calles de la ciudad. La atmósfera es extrañamente moderada. El helicóptero aún se encuentra flotando en el aire, emitiendo su amenazante y aparentemente interminable gruñido. Ceno algo en una cafetería de la acera del Passeig de Sant Joan, a solo unas cuadras de donde se llevaron a cabo los acontecimientos tan importantes de ese día. No presencio bailes en las calles, ni jolgorios ruidosos de ningún tipo. Solo unos pocos rezagados con sus banderas catalanas colgadas sobre sus hombros. Le pregunto a mi mesera—quien me dice ser oriunda de Marruecos— qué piensa de los eventos de hoy. Se acerca un poco y adopta un tono confidencial. “Esta es una ciudad muy bella”, dice, “y van a arruinarla con sus idioteces”. Le pregunto sobre el helicóptero. “La policía nacional”, explica. “¿Y qué crees que va a pasar ahora?” Coloca una muñeca sobre otra, como si la hubieran esposado. “Todos a la cárcel”, dice con un brillo en los ojos.

Por la mañana, miro algunos canales de noticias. CNN declara que el parlamento catalán votó “abrumadoramente” por la declaración de independencia. No se menciona el hecho de que cincuenta y cinco legisladores abandonaron la sesión parlamentaria de ayer, no queriendo participar en lo que consideraron una votación ilegal. De los ochenta diputados que participaron en la votación, setenta votaron por el “sí”. Eso suma setenta de un total de ciento treinta y cinco diputados. El Washington Post publica un artículo con un cierto tono de simpatía por los secesionistas, pero con una extraña mezcolanza de perspectivas izquierdistas y derechistas. Primero, hay una cita de un columnista de izquierda, que iguala la lucha catalana por la independencia con la lucha por la democracia frente a un estado opresivo. Enseguida, escuchamos a un columnista de derecha que concede la razón a los catalanes de no querer compartir su riqueza con sus vecinos más pobres en otras partes de España. Los catalanes, dice el artículo, se sienten “encadenados a un cadáver”. Me pregunto qué sentiría un madrileño o una sevillana, o para el caso, cualquier persona de cualquier otro lugar de España si leyeran esto…

Después de pasar la mañana leyendo en mi cuarto de hotel, salgo a la calle alrededor del mediodía. El día está nublado y en comparación con los días anteriores hace un poco de frío. La ciudad comienza a verse otoñal, envuelta en una luz grisácea. Las hojas de los enormes plátanos que bordean las avenidas muestran un aspecto cansado mientras esperan caerse suavemente al suelo. Me siento en un café al aire libre en la calle de la Marina y pido un bocadillo. Los transeúntes son una mezcla de lugareños y turistas moderadamente bien vestidos que regresan de una visita a la catedral de la Sagrada Familia, ubicada a pocas cuadras de allí. Después de terminar mi almuerzo, camino por la Gran Vía en dirección a la Rambla de Catalunya. En la Casa del Libro, compro dos títulos: Sudor de Alberto Fuguet y una colección de ensayos sobre Albert Camus de José María Ridao, el orador que escuché ayer. Hay muchos compradores asiduos vestidos a la moda que pasean por las calles en esta parte de la ciudad. Finalmente, ha salido el sol y sopla una brisa fresca. Me dirijo a la Plaça de Sant Jaume y la encuentro repleta de reporteros y cámaras. Tomo fotos del ajuntament y del Palau de la Generalitat. Para mi sorpresa, veo que la bandera española sigue ondeando sobre ambos edificios.

De pronto noto un tumulto en la plaza. Un hombre de unos sesenta años, con sobrepeso, llevando una bicicleta deportiva y vistiendo un ajustado atuendo de ciclismo rojo y negro, grita algo a los policías que custodian la entrada a la Generalitat. Camina con su bicicleta hacia el centro de la plaza, donde un periodista le hace algunas preguntas. Me acerco para escuchar. El hombre está enojado. “¡Esto es España!”, grita, mientras parece estar cortando el aire con su brazo derecho. Señala al suelo. “¡Yo estoy en España!”, declara. El reportero le hace una pregunta que no puedo escuchar. Ahora oigo que describe a los líderes del movimiento secesionista como “mentirosos” y “farsantes”. Todos, grita, deberían volver a trabajar el lunes. “¡A trabajar!”, exclama, mirando furiosamente a la gente que se ha reunido para escucharlo.

En otra parte de la plaza, una mujer sonriente de mediana edad está hablando con otro periodista. “Nunca nos dejarán ir”, dice, casi alegremente, refiriéndose al resto del país. “Somos lo mejor de España”, agrega. Se ve muy complacida con su análisis. “Somos la coca”, concluye. La periodista agradece a la dama sus palabras.

De vuelta en la habitación de mi hotel, me paso la noche viendo las noticias. Una representante de uno de los partidos independentistas insiste en que varios países están a punto de reconocer a Cataluña como una nación independiente. Eslovenia, Finlandia, Argentina … la lista no es muy larga. Se informa que Carles Puigdemont ha regresado a su ciudad natal de Girona, donde se la ha visto el sábado, a la hora del almuerzo, disfrutando de una copa de vino en un bar, mientras se ve a sí mismo en la televisión entregando una breve declaración en la que rechaza su destitución por el gobierno central de España, y pide a los catalanes que resistan de modo pacífico la imposición del artículo 155 de la Constitución española.

Para el lunes, estoy de vuelta en Los Ángeles. Puigdemont ha abandonado Cataluña y se encuentra en Bruselas. Una amiga me informa que Manuel Castells, el eminente sociólogo catalán, dará una charla sobre la situación en su país en la Universidad del Sur de California, donde ocupa una prestigiosa cátedra. Más tarde, mi amiga me cuenta que hubo un enfrentamiento entre Castells, que apoya la independencia, y el cónsul español en Los Ángeles, que había asistido a la charla. Según mi amiga, Castells había argumentado que el apoyo a la independencia se incrementó después del duro intento del gobierno español de detener el referéndum del 1 de octubre. El comentario me recuerda lo que mi taxista me había dicho en el camino al aeropuerto de Barcelona el domingo. ¿Qué cree que pasará ahora? yo le había preguntado. Depende de lo que haga el gobierno español, me había contestado. Si reacciona de manera exagerada, llevará a más personas al movimiento independentista. Castells también había afirmado que las últimas encuestas mostraban que el bando independentista ganaría las próximas elecciones. Cuando reviso las encuestas yo mismo, descubro que la confianza de Castells en la victoria de su causa resulta injustificada. El electorado catalán está profundamente dividido, y el resultado de las elecciones sigue siendo muy difícil de predecir.

*Imagen de portada de Sasha Popovic

Maarten Van Delden es autor de Carlos Fuentes, Mexico and Modernity (Vanderbilt University Press, 1998) y, con Yvon Grenier, coautor de Gunshots at the Fiesta (Vanderbilt University Press, 2009)

Maarten Van Delden es autor de Carlos Fuentes, Mexico and Modernity (Vanderbilt University Press, 1998) y, con Yvon Grenier, coautor de Gunshots at the Fiesta (Vanderbilt University Press, 2009)

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

A well written account of someone who is witnessing history, a peaceful revolution with no end in sight.