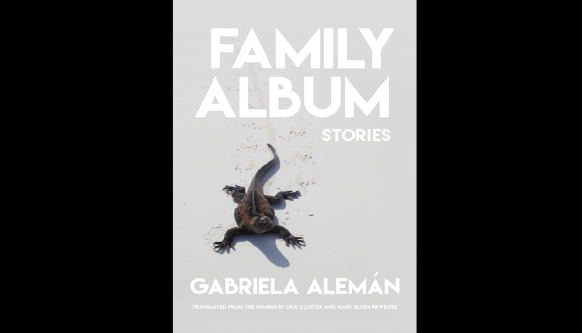

Family Outing

Gabriela Alemán

Translated by Dick Cluster

In his account of traveling along the Orinoco, Humboldt describes a strange ritual in which the native people go into the depths of a cave to catch birds with pitch-black feathers they call tayos. As they penetrate the cavern, the men bang enormous river-bottom rocks and shake rattles made of dried animal hooves. This bewilders the tayos, blind birds with oily plumage, who are extremely sensitive to sound. Then the men hurl themselves upon the birds, but seizing them is not easy because they are slick as greased lightning, and the floor of the cave tilts abruptly toward an abyss. In the German natural- ist’s description, the tayos have faces like aged children, rendered more sinister by their seemingly empty eye sockets. The combination is only slightly less disturbing than the spearing of their chicks that follows. As night falls, after impaling the birds, the men set them on fire. Their steady glow will illuminate the men’s nocturnal excursions.

None of Humboldt’s writing succeeds in describing the terror he felt on witnessing the hunt, the impaling, and the subsequent conversion of the birds into torches. He takes refuge in the language of science, but this proves insufficient, and he finally abandons it.

The caves of the Ecuadorian Amazon are full of tayos, those birds in whose empty eyes it is not hard to imagine hell or its ter- restrial equivalent: the decaying expanse of jungle that fosters dis- sipation and disillusion. Where only the dregs are likely to prosper.

♦♦♦

I picked up the notebook dropped by the geologist who was recov- ering next to me in the drilling platform’s sick bay off the coast of Louisiana, and I read that passage in his diary. This was my introduction to Ecuador, which I had never heard of before. It came soon after I had realized I needed to flee the country, because no place in it seemed safe for me. I had left too many tracks in too many places. I needed to start over. The Ecuadorian jungle sounded just like the ticket.

♦♦♦

These guys had no idea what they were getting into. They’d be mowed down like children wandering into a crossfire, but nobody asked my opinion, and when I saw their eyes glowing with savior spitfire, I refrained from offering it. I had seen that expression too many times not to recognize the fanatacism that went with it. Still, keeping my opinion to myself didn’t mean I wasn’t getting tired of lying on a bed covered with rat shit. I was fed up with shaking out my sheet every morning and heading for the riverbank to skip stones or watch the detritus of the jungle float by while I waited out the day, only to go back after dinner and find the sheets covered in shit yet again. If we didn’t leave soon the rats would wind up gnawing at my fingertips while I slept. They’d already tried it once, and, I’d mistaken it for the tiny teeth of a child nibbling at me. If the sensa- tion hadn’t been so pleasant, I wouldn’t have moved, wouldn’t have caught the rodent between my leg and the straw mat that served as a wall, and it wouldn’t have squealed and woken me up. From that night on, I couldn’t sleep. If we got a move on, I’d make it. But if I stayed there staring at the ceiling, imagining the future, the rats were going to eat me alive.

I don’t know what the guys were waiting for. However much I had decided this was the best place in the world for me, I was starting to doubt my decision to abandon the oil company camp to join these self-styled saints in their peaceable assault on the Huao. I’d had my eye on my grand plan, on the long term, rather than the short, but now, every time I had to watch them wrestling with each other or swapping dumb jokes or referring to themselves as messen- gers, I was ready to throw up. What game were they playing? Saving souls, truly? I couldn’t see any other explanation. At nineteen years of age, nobody could be so stupid except someone who thought they had a monopoly on the truth. And if, in 1957, they believed that such a thing existed, then the only proper word for them was imbeciles.

During my sixth flying lesson, they started asking too many questions. They wanted me to hand over my papers to the Summer Institute of Linguistics. They started to have their doubts about me. They told me it was just to keep my documents in a safe place. Yeah, right.

“When I go to the office, who do I tell what I’m doing here?” I asked, averting my gaze while digging at my gums with a toothpick.

After that, they stopped pressing me, even though I still made them nervous — which was, of course, why they’d hired me. But try explaining that to a handful of illuminated brats. Not that that was any of my business. What I did ask was for them to show me the firearms we were going to take with us. I wanted to get used to them, and at least teach the kids how to hold them. Of the five, one refused. That was fine with me, but when he tried to explain his logic, I stood up and walked away. Let him waste his breath on his congregation or whatever he had in that fifth circle of hell where everything rotted at soon as it was exposed to the air, including his notions of salvation. Because from what I could see, there was a seri- ous hole in their plan if they wanted to go armed into the territory of some Indians who had been hounded by settlers for ages. And for what reason? To save their souls.

I didn’t need to teach anybody anything, it turned out. They were healthy farm boys from the Midwest. Every one of them had picked up his first gun before he was six. They knew as much as I did about firearms.

But I used the occasion to ask them some questions, in spite of knowing beforehand what the answers would be. Really, I did it because I wanted them to hear how they were lying to themselves.

“So what do you need me for?” I asked Nat, the leader of the expedition.

“I told you, to come along with us.”

He was shining a pair of boots. You had to either admire him or dismiss him as an idiot. As soon as he put the boots on, his hour’s worth of work would go to waste.

“What for?”

“To shoot in case of trouble.” He smeared more black polish on the leather.

“You could do that yourselves.”

“No, we couldn’t . . .” He left the rest of the sentence unsaid. “Because it would have to be shoot to kill,” I finished for him. “Right?”

When he lifted his head, he looked at me blankly. Then he cocked it to one side and answered me as if I were the idiot.

“That’s in the ballpark.” He kept on rubbing his worn-out flan- nel polishing cloth over the boot.

♦♦♦

Nat was the one who’d approached me while I was overseeing the cutting and clearing of land for the new oil camp. I had twenty men under my command and was generally said to be the best crew boss around. The one who, at the end of the day, had cov- ered the most territory. Nat was an observant kid. He saw how hard those peasants helicoptered in from the mountains were working. He admired what he thought was our team spirit, and he liked the way I kept control. He spent five days wandering the camp until Sunday rolled around and he came in with the pretext of spreading the word of God and walked up to me. The Bible in his hand was in Spanish instead of Quichua, but in truth it didn’t make any difference since English was all he spoke. Finally, we went for a few beers. He didn’t even finish the first, but it seemed to be too many. He told me his wife was pregnant and he wanted a little action and he had an idea but he needed somebody like me in order to carry it out.

I was bored. Staring at the jungle leads either to madness or to reflecting on the meaning of life, and metaphysics is a discipline that, to my way of thinking, only fits in the asshole of a wild boar. That was the sole reason I listened to him.

“Do you know why they obey me?” I asked while rolling a cigarette.

“No,” he answered. He set his bottle down on the table to con- centrate on me.

“Because the first time we hit the trail and someone stopped walking, I shot him in the stomach and let him bleed out for the rest of the day while the others worked.”

I licked the edge of the paper and finished rolling the smoke.

The kid laughed nervously. I watched him considering his options.

“You didn’t do that,” he said after a pause. “You couldn’t have, if you did you’d be in jail, not talking to me.” He tried to keep his tone light.

“What sheriff was going to arrest me?” I was starting to enjoy this.

“Somebody would have reported you,” he insisted.

“Who?” I opened another bottle. “And to whom?”

He started to squirm in his seat, giving this more thought. For the first time, he seemed to realize where he was. I enjoyed the dis- comfort that passed over his face. He leaned back and didn’t say another word. I stood up and left him with the tab. I didn’t say goodbye. A week later, he was back with a business proposition. When he finished explaining it, I asked him what I’d get if I said yes.

“Name your price,” he replied. It was pitiful, watching him play-act in the jungle like that.

Still, learning to fly in return for going along with them didn’t seem like a bad deal. So that’s how I found myself killing time by the river in the missionaries’ camp, waiting for them to get ready. Once I had seven flight hours under my belt and Nat had signed a document with the seal of the SIL saying I knew how to fly, I thought maybe these kids could convert me after all. Being able to fly a small plane in the jungle was like having a first-class boarding pass to a new life.

From what I could make out from their conversations, there was a big competition under way for the souls of the Aucas, as the Huaos were called in the camps. Whoever got first access to them would be seen as the superstars of faith. They wanted that honor. It was a lot more exciting than scratching at mosquito bites while tuning in to the Voice of the Andes in their cement bungalows in the middle of the jungle. It was better than waiting for the snakes, the heat, or boredom to do them in. But, if they had set their sights on the Indians’ souls, others wanted those same souls to disappear, so as to get access to their lands. All the means proposed by either group seemed to have been grabbed off the first vine dangling over a trail. When I came into the picture, the method was still to try and pacify them by dropping presents from the sky. They thought they could convince the Indians with trinkets. The Huao didn’t turn up their noses at the presents. They took them, and meanwhile contin- ued attacking any intruders who came close to their lands. Later, thanks to the aerial photos that the oil companies had made while flying over their territories, the companies knew where they moved and where they lived. With that information, the next step was to drop dissuasive bombs on their huts — to burn their houses to get them to move farther away from the camps. The wisdom of the oil companies matched that of the missionaries. On this occasion, while fire fell from the sky, the Huao threw spears into the air, expecting to be able to hit the metal birds. Then they disappeared into the jungle to prepare for the next attack. Among all the proposed solu- tions, one was to gas the Indians, bundle them into boats, and move them hundreds of miles away from their land so they could keep liv- ing in their time-out-of-time while the flourishing slum civilization made its way into the jungle.

My guys had more specific ideas, though no less perverse. They were going to go into the Huao territory and build a treehouse on the riverbank, as close as possible to one of the cultivated plots. From this sanctuary they would film and observe the savages. They would park the plane that brought them there on the bank and offer trips into heaven. They’d bring gifts, they’d behave in friendly fashion, and, hearts overflowing with love, they would succeed in converting the heathen. That was their plan, which they held to be flawless. They didn’t tell their superiors what they were up to, nor give any signs of where they were going. The only precaution they took was to hire me and arm me to the teeth. That way, they could wash their hands of it if anything went wrong. We were made for each other. If they were devoting their lives to the pursuit of souls, I was devoting mine to the pursuit of despair. We were two sides of the same coin. If they had realized this, they would have tried to part ways, to separate their purity from my mud. But wouldn’t they have eventually figured this out? That the two sides rub against the same skin when the coins are held tightly in a fist? In this case, the jungle was the fist. They couldn’t get rid of me. They wouldn’t have known how.

One afternoon, they came down to the river to tell me we’d be leaving the next morning. And we did — the five of them and me, in the plane, which also carried a number of crates of presents and provisions. First, we flew over the huts of the Huao, dropping some of the gifts to make them well-disposed toward us when the hour of contact would arrive. Then we landed on a strip of sand on the riv- er’s edge. The boys kept close together, spending the first morning building a small platform and a rope ladder for getting up the tree. Once aloft, they nailed in three bigger boards and fitted a tarp to serve as a canopy. Then they came down, played American football, took pictures, and blared some kind of music I’d never heard in my life. While they played, I dug a trench on the highest ground of our terrain and then started leafing through some of the scientific maga- zines they had brought along to give away. The photos were mostly of skulls. For me this confirmed that they all had a screw loose, and I made sure my weapons were loaded and that I had plenty of reserve cartridges close at hand. What would I think if a bunch of strang- ers who didn’t speak my language showed up at my village and offered me pictures of skeletons? Nothing good was going to come out of this. I hardly slept that night. In the morning they lit a fire, made coffee, and opened a can of Virginia ham. I ate enough but not too much, because I wanted to stay alert. Around noon, down to the river came a group of naked women with decorative ribbons around their hips. I gave them the attention they deserved, but no more. What mostly caught my eye was the group of children who came with them. I thought of heading for the beach right away, but I thought I’d have enough time later and it was better to keep cover- ing the rear. The women acted friendly and smiled a lot, they tried on the clothes the missionaries had brought, they looked in the mir- rors, cast an eye on the magazines, and then left. We ate sandwiches and then three of the guys swam in the river while the other two chatted near the bank. They were all in a good mood. They thought things were going just fine.

At about four, some women reappeared, laughing, but looking nervous. This time they had no kids along. There was something in the air, an electric charge that accompanied them. They approached slowly, the youngest one kept looking toward the jungle. I got in my trench and saw shadows moving through the trees. The attack came, a perfect ambush, but I was ready to shoot. I didn’t do it because the boys had made it clear I was to let them take the initiative if something happened. I was sure they had told me this because the possibility of an ambush never crossed their minds. They rushed for their guns. If there was going to be a massacre, the blood would still be on my hands, but it wasn’t like they came in with only their prayers as their shields. They were fundamentalists, but they valued their skins. Even the fifth one, who had refused to carry a pistol back in the mission was packing one now. Like I said, they knew how to lie to themselves. They tried to calm things down, repeating the only Huao word they knew, which meant “friend” — all the while brandishing their pistols in the air. Causing a great impression, it was immediately clear. More than fifteen spears rained down, hit- ting two of them right away. The third ran for the plane while the fourth put his gun on the sand and raised his hands. A spear split open his shoulder and his clavicle while another one went through his throat. The fifth guy retreated toward the river and began firing wildly. The one who had run for the plane didn’t think of start- ing the engine, just fired away through the windshield once he got inside. Meanwhile two Indians speared him through the open doors of the plane and started pulling him toward the beach. The one missionary who had retreated, who was in the river headed down- stream while emptying his clip, managed to hit one of the Huao in the forehead. The roar from his fellow warriors shook my spine. This time the spears came from three directions and one went right through the shooter’s back. Then, when the wounded Huao fell, they came for me. There were more than twenty, and they seemed like birds gliding over the sand. I figured that to survive I’d have to kill five of them at least. I hit them in their chests and they collapsed right away. The others stopped and saw that, although I was still aiming at them, I had stopped shooting. They recognized the uni- versal sign of a truce and retreated toward the jungle, dragging their dead. If I took the plane and returned to the mission, I’d end up in jail. As soon as someone checked out who I was in the States (and I was sure the embassy would get involved), that would be the end. My other option was to follow the river, hoping no pursuit resumed before I could find a settler or an oil camp. I grabbed a canvas bag, stuffed it with provisions and all the ammunition we had, and fol- lowed the river. Over the next few days, a deluge made it overflow its banks, so I ended up wandering like a ghost through the recesses of that damned jungle. I don’t know how much time went by. I just know that when I woke up, I could hardly open my eyes from the bites all over my body, and that not even during my attacks of fever did I tell what I had seen. The logger who found me half dead inside the trunk of a tree and saved my life told me I’d ended up at the oil company camp because he was felling trees without a permit and he would have had to answer too many questions if he took me all the way down to the clinic in Coca.

While I recovered, I followed the news about what the press, both local and foreign, was calling the “Auca assault.” A U.S. army delegation came from their base in Panama to investigate, while Life magazine made the incident the main story in their next issue. I didn’t want anything to do with it. I was careful not to ask any questions, but I did read the clippings that came into my hands. I acted as surprised as anyone else. I only listened to the news when the head nurse tuned in the radio. Everything said were lies, they grabbed explanations from the same vines from which they had grabbed solutions for relocating the Huao. Now they had reasons to attack the savages and do away with them. That plan was backed up by reports from the American and Ecuadorian militaries and the oil company security force. Such a neat little packet they put together. Who could object to laying siege to the murderers of a group of defenseless missionaries? Every time that phrase recurred, I succumbed to a bout of nausea and vomiting. The doctors thought I had malaria, but it was just a reaction to what the boys had achieved. They not only got to be stars; they had become martyrs. With their deaths, they succeeded in separating the two sides of the coin. The mud over there, and over here, the crystal clear word of God. Nothing was ever said about the shell casings that must have been scattered over the beach. That never appeared in any report.

I decided to forget about it, and, so as to bury the episode com- pletely, I converted. I did it for the same reason that makes believers of us all, because in the end you believe what’s good for you. I didn’t care about the Huao. I cared about my skin and that nobody should connect me to them or to what had gone down. Thanks to the faith I demonstrated, I succeeded. And thanks to the martyr and his teach- ings, I managed to get a job as a pilot once I was well. When I fly, I still see them wandering through the paths of the jungle. From above, you can hardly make them out. When they hear the sound of the engine, they disappear like shadows in the trees. From the air, I can’t stop thinking about what Nat said to me once when we saw them during a training flight: the Aucas were a quarter mile distant from us vertically, fifty miles horizontally from the mission, and many continents and oceans away, psychologically. He was wrong to include me. When I remember his words and think about him, those measurements feel basic compared to the distance that sepa- rated us, me and him. The distance that separates any human being from those who can talk with God.

“Family Outing” from Family Album: Stories. Copyright © 2010 by Gabriela Alemán. Translations © 2022 by Dick Cluster and Mary Ellen Fieweger. Reprinted with the permission of City Lights Books. www.citylights.com

Gabriela Alemán was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She received a PhD at Tulane University and holds a Master’s degree in Latin American Literature from Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar. She currently resides in Quito, Ecuador. Her literary honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006; member of Bogotá 39, a 2007 selection of the most important up-and-coming writers in Latin America in the post-Boom generation; one of five finalists for the 2015 Premio Hispanoamericano de Cuento Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia) for her short story collection La muerte silba un blues; and winner of several prizes for critical essays on literature and film. Her novel Poso Wells was published in English translation by City Lights in 2018.

Gabriela Alemán was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She received a PhD at Tulane University and holds a Master’s degree in Latin American Literature from Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar. She currently resides in Quito, Ecuador. Her literary honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006; member of Bogotá 39, a 2007 selection of the most important up-and-coming writers in Latin America in the post-Boom generation; one of five finalists for the 2015 Premio Hispanoamericano de Cuento Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia) for her short story collection La muerte silba un blues; and winner of several prizes for critical essays on literature and film. Her novel Poso Wells was published in English translation by City Lights in 2018.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: July 21, 2022 at 10:47 pm