Latin America and the World at the Pre-9/11 Juncture

América Latina y el mundo en la coyuntura pre 9/11

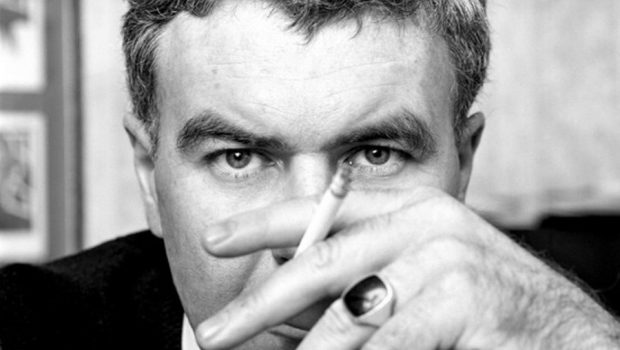

Marc Zimmerman

In the memory of Eduard Delgado,

the Director of Interarts, who lost his battle

against cancer in 2002.

In 1979, when I was the only yanqui working at the recently created Ministry of Culture in Sandinista Nicaragua, a Marxist- Leninist Colombian who was employed as a professor at a Canadian university paid us an emergency visit in order to alert the comandantes that Willy Brandt, François Mitterand, Felipe González, and company were conspiring to distort the revolutionary alternative by convincing Nicaragua and other Central American rebel countries to unite as a block—led by Mexico and Venezuela—so that, in association with European social democracy, they might be able to resist American pressures without yielding to the Soviet side. My Colombian friend was very concerned about this and was frustrated when he found that the Sandinistas had already heard about the plan, and that at least one of the nine comandantes had even indicated that it was the only way to resist American imperialism and build a new society.

I have always kept this incident in the back of my mind, since for me this was a possible, perhaps even desirable, solution for problems that seemed impossible to solve any other way. The situation came to mind again some years ago when I received an invitation from Barcelonan cultural activist Eduard Delgado to attend a conference dedicated to Euro-Latin American relations. In his announcement, Delgado cited “the lack of formal instruments to encourage and govern Euro-American relations, especially in these Post-Cold War/Globalizing times.” In this situation, he said, “Europe needs Latin America more than ever in its search for values that compensate for and correct the loss of public spaces that stimulate coexistence, social life, and creativity.”

I’m very much in agreement with this vision. It’s a line of thought present in the texts of Leopoldo Zea and Enrique Dussell— a romantic and humanist line of thought that honors the best of Europe, represented by Las Casas and perhaps Cervantes. However, I believe that it’s important to remember the clear implication of this Euro-Latin American issue: that the traditional values sought by Europeans were, what at least one human being called, “surplus values.” Naturally, that was the humanist tradition. But we should also remember that Bolivar’s dream, typical of pro-independence criollo thought at the beginning of the 19th century, was to liberate Latin America from Spain in the name of a freedom denied to the non-Western cultures and peoples living and working the land and mines of America.

These questions form part of a complex history that has to do with slavery, mestizaje, and the typical themes of “civilization and barbarity,” in addition to a number of other things. According to that history, economy, politics, and even technology and science are cultural matters. The theory is that Latin American cultures obstruct technological advances and the development of the political and economic trends vital to that development. In this regard, elite Latin Americans of European descent have felt frustrated with the precapitalist and premodern elements of their countries of origin and have thus always sought links with Europe. Even today a certain tension exists between the values and cultural norms promoted by the descendents of the criollo and mestizo elites, vs. those that derive from sectors still linked to forms of popular culture, rooted in entirely different socioeconomic systems, to the extent of having been hybridized, globalized, recycled, and transformed by massive cultural processes. However contemporary they may seem, these cultural processes contain a distinct residue of preindustrial values that the elites consider contrary to the progress and reason that are essential to the European.

Certainly advanced and “cyberneticized” countries need some residue of community and solidarity, but without the descent into ethnic and territorial conflicts that have dominated recent history. However, it’s no less true that projects connecting Europe and Latin America (and perhaps particularly those involving Spain) are regarded with mistrust, ambivalence, and at times, open hostility; as if they might somehow represent a continuation of the colonial relationship. Generally the problem intensifies when the interests of Latinos in the U.S. are involved, because they perceive those projects to be a strategy to gain access to North American possessions. And that’s due to the fact that the Latino leadership, Cubans aside, believes theirs is, or at least represents, the sector least connected to the criollo elites, whose traditions remained more intact.

With respect to Spain, perhaps the most notable example of Latino hostility I have personally witnessed was when, with the blessing of the Socialist government, the INCE of Madrid invited Latino leaders and some academics, including myself, to speak regarding the participation of Hispanics in the U.S. during the 500th anniversary celebrations. The answer was that Latinos in the U.S. didn’t have anything to celebrate on that occasion, and that their leaders weren’t going to betray their communities by sponsoring festive events.

The efforts of the IRELA (Institute for European-Latin American Relations) to promote economic growth and cooperation between Europe and Latin America could possibly represent a new phase. However, it seems to me to be important that organizations that are neither associated or identified with any type of Castilian centralism (governmental or Madrid-based) already have their own Euro-Latin American projects, linked to their own interests and aspirations. In my opinion, it is especially noteworthy that in a period of globalization and alleged Latin American democratization, organizations such as Interarts have stressed, not economics, but rather issues, relationships, and cultural politics. This emphasis on culture is important, even if only because the cultural sphere is where we can more easily find crucial points of difference and convergence; and furthermore where economic, social, and political issues meet more traditionally with success or failure.

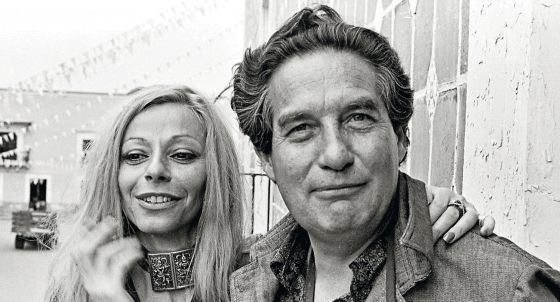

Ever since the loss of its territories Spain has claimed a special relationship with Latin America; and naturally, many Spanish families are closely connected to certain places in Latin American. Moreover, the Civil War dispersed Spanish intellectuals (including Basques and Catalonians) all over Latin America, the full impact and continued effect of which still remains to be studied. I believe that one could say that, its relationship with the conservative Latin American criollo elite aside, Franco’s Spain was considered arrogant and condescending; even after becoming a refuge for numerous political exiles from Latin America, contributing thus a great deal to the boom of Latin American literature. During the Felipe González administration, despite certain troublesome and contradictory effects related to the celebration of the 500th anniversary and other matters, relations improved considerably, with increased good will, broader and more democratic projects, etc. Meanwhile, Spain’s economic expansion—through the development of new large-scale business initiatives, not only in Cuba but across the region—represented what some, perhaps exaggeratedly, have called the second Spanish conquest of Latin America.

In order to understand European and Latin American relations today, the agenda must include these and many other themes. There is, moreover, the question of intellectual Eurocentrism, that affects the same categories of knowledge through which those themes are studied, independent of the birthplace of the theorist or the concrete thinker. Yet, what seems to me to be most important to highlight, in terms of our deliberations, is that the issue of Euro-Latin American relations does not have as much to do with cultural policy, the line descending from force and authority, as it does with cultural politics, the resistance of the base to forge and maintain cultural spaces and modes. In spite of the romanticisms and the existence of many non-democratic culture groups, I consider multicultural democratization a crucial factor in political, and ultimately, economic democratization. Hence, I usually focus on people, rather than on national spaces. That brings me to the notion that immigration and settlement issues, and the cultural forms generated by those immigrations, reproduce models and problems more similar to those in America and Europe. In an email I received, Professor Sandra Ponzanesi announced her conference as follows: Increasing mass migration is redefining actors, places, and languages in European writing. These cultural shifts are magnified in the writing of cosmopolitans, expatriates, exiled as all migrants. By and large, the languages of the most powerful ex-colonisers (English and French) have been the privileged medium of expressing straddling nations, cultures and identities. However, other migrant traditions (such as those expressed in minor ex-colonial languages or vernaculars) are mapping new literary and cultural spaces. At the dawn of the new millennium it is important to assess the different material backgrounds that colour all these texts and acknowledge in what way they contribute to rewriting, expanding and subverting existing notions of European identity and citizenship.

It’s not simply about the parallels between immigrant workers and their impact on America and Europe, but also of direct Latin American economic immigration dispersing all over the European space. Here emerges a parallel with the recently published exploration by Mike Davis (2001) on the “Latin- Americanization” of cities in the U.S. as the model for the “Latin-Americanization” of at least certain dimensions of European cultural life. One can easily begin with the Iberian Peninsula, as an obvious nucleus of Euro-Latin American relations; however, England and the rest of Europe are also affected. In this sense, studies relating to domestic work and prostitution in the Dominican population in Madrid joins the increasing international literature in this field, whose most outstanding examples are not always Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, or others in the U.S., but also Colombian workers in Venezuela, Nicaraguans in Costa Rica, Ecuadorans in Italy, etc.

If we focus on cultural politics in addition to cultural policy we find ourselves in such fertile areas of study as macroeconomic and political issues. Moreover, we’ll find that many Latino (or Hispanic) groups of the U.S., equally preoccupied with resisting and establishing themselves, may offer important insights on Euro-Latin American relations. Although I’m not trying to attribute to Latinos a role of deep spiritual reserve among the working class of a world economic giant, they could play a significant role in connection with the contemporary narrative of modernization within the context of globalization, and in the transformations of Latin America, the Third World, and beyond.

• Marc Zimmerman is the Chair of the MACL at the University of Houston. He has written and edited some thirteen books, including U.S. Latino Literature (1992), and New World [Dis]Orders (1998).

Dedico este texto a la memoria de Eduard Delgado,

Director de Interarts, quien perdió su batalla

contra el cáncer en 2002.

En 1979, cuando yo era el único yanqui trabajando en el recién creado Ministerio de Cultura de la Nicaragua sandinista, un colombiano marxista-leninista que ejercía de profesor en una universidad canadiense hizo una visita de emergencia para alertar a los comandantes de que Willy Brandt, François Mitterrand, Felipe González y compañía estaban conspirando para distorsionar la alternativa revolucionaria, pretendiendo que Nicaragua y otros países rebeldes de Centroamérica se unieran a un bloque liderado por México y Venezuela y que, asociado a la socialdemocracia europea, pudiera resistir las presiones estadounidenses sin caer en el bando soviético. A mi amigo colombiano le preocupaba mucho tal posibilidad y quedó frustrado al ver que los sandinistas ya sabían de dicho plan, y que al menos uno de los nueve comandantes había incluso indicado que era la única forma de resistir al imperialismoestadounidense y de construir una nueva sociedad.

Siempre he tenido presente este caso, ya que también para mí esta era una solución posible —quizás incluso deseable— para problemas que de otro modo se antojaban irresolubles. La situación me volvió a la memoria hace poco, tras la convocatoria de Eduard Delgado para un campus centrado en las relaciones euro-latinoamericanas. En su convocatoria Delgado citaba “la falta de instrumentos formales para estimular y regular las relaciones euro-americanas, especialmente en estos tiempos post-guerra-fría/globalizantes”. En esta situación, decía él, “Europa necesita de América Latina más que nunca en su búsqueda de valores que compensan para corregir la pérdida de los espacios públicos de la coexistencia, vida social y creatividad”.

Estoy muy de acuerdo con esta visión. Es una línea de pensamiento presente en los textos de Leopoldo Zea y Enrique Dussell. Línea de pensamiento romántica y humanista que honra a lo mejor de Europa, representada por Las Casas y, quizá, Cervantes. Pero creo que es importante recordar las evidente implicaciones de esta cuestión euro-latinoamericana: que los valores tradicionales buscados por los europeos eran lo que al menos un ser humano llamó “la plusvalía”. Naturalmente, estaba la tradición humanista. Pero deberíamos recordar también que el sueño de Bolívar, típico del pensamiento independentista criollo de principios del siglo XIX, era liberarse de España en nombre de una libertad que sólo era negada a las culturas y los pueblos no occidentales que vivían y trabajaban en las tierras y minas de América.

Estas cuestiones forman parte de una compleja historia que atañe a la esclavitud, el mestizaje, los típicos temas de “civilización y barbarie” y otras tantas cosas. Según esa historia, la economía, la política e, incluso, la tecnología y la ciencia, sontambién materia cultural. Dice la teoría que las culturas latinoamericanas dificultan el avance tecnológico y el desarrollo de las tendencias políticas y económicas tan importantes para dicho desarrollo. En este sentido, las elites europeas de América Latina siempre han buscado vínculos con Europa y se hansentido frustradas con los elementos precapitalistas y premodernos de sus países de origen. Aún hoy existe cierta tensión entre los valores y normas culturales promovidas por los descendientes de las elites criollas y mestizas y los que se derivan de sectores todavía vinculados a formas culturales populares, incluso habiendo sido hibridados, globalizados, reciclados y transformados por procesos culturales masivos, enraizados en sistemas socio-económicos totalmente diferentes. Por muy contemporáneos que parezcan, estos procesos culturales tienen cierto residuo de valores preindustriales que las elites consideran opuestos al progreso y la racionalidad instrumental a la europea.

Es seguro que los países avanzados y “cibernautizados” requieren cierto residuo de comunidad y solidaridad, sin caer en los conflictos étnicos y territoriales que tanto han dominado la historia reciente. Pero no es menos cierto que los proyectos que relacionan a Europa y América Latina (y quizás en especial los que implican a España) son vistos con recelo, ambivalencia y, a veces, abierta hostilidad, como si constituyeran de algún modo una continuación de las relaciones coloniales. Y generalmente el problema se intensifica cuando están afectados los intereses de los latinos de E.U., percibiéndose tales proyectos como una estrategia para adentrarse en las posesiones estadounidenses. Y eso porque la dirección de los latinos cree ser, o al menos representar, aparte de los cubanos, el sector menos ligado a la tradición de las elites criollas, aquél cuyas tradiciones fueron menos pisoteadas. Por lo que a España respecta, quizás el ejemplo más notable de hostilidad latina que personalmente he presenciado llegó cuando, con la bendición del gobierno socialista, el INCE de Madrid invitó a líderes latinos y a algunos académicos como yo a tratar sobre la participación de los hispanos de E.U. en lasc elebraciones del Quinto Centenario. La respuesta fue que los latinos de E.U. no tenían nada que celebrar en tal evento y que sus líderes no iban a traicionar a sus comunidades promoviendo actos de naturaleza festiva.

Lo que sí podría representar una nueva etapa son los esfuerzos del IRELA (Instituto de Relaciones Europeo-Latinoamericanas) por promover el crecimiento y la cooperación económica entre Europa y América Latina. Pero me parece muy importante que organizaciones que no trabajan ni se identifican con cualquier tipo de centralismo castellano, gubernamental ni madrileño tengan sus propios proyectos euro-latinoamericanos, vinculados a intereses y aspiraciones propios. En el caso de Interarts, me parece especialmente destacable que en un periodo de globalización y supuesta democratización latinoamericana, se haga hincapié no en la economía sino en cuestiones, relaciones y políticas culturales. Ese énfasis en la cultura es importante, aunque sólo sea porque es en el ámbito cultural donde más fácilmente podemos encontrar puntos cruciales de diferencia y convergencia y también donde las cuestiones económicas, sociales y políticas se encuentran con su éxito o su fracaso.

Desde la pérdida de sus territorios, España reclama su relación con América Latina y, por supuesto, muchas familias españolas están muy vinculadas a determinados espacios latinoamericanos. Obviamente, la Guerra Civil dispersó a intelectuales españoles, vascos y catalanes por toda América Latina, cuyo pleno impacto y continuado efecto tiene todavía que ser estudiado. Creo que podría decirse que, aparte de su relación con las elites criollas latinoamericanas más conservadoras (“castizas”), la España franquista era considerada arrogante y condescendiente, incluso tras convertirse en refugio de numerosos exiliados políticos de América Latina y contribuir mucho al boom de la literatura latinoamericana. Durante los gobiernos de Felipe González, pese a ciertos efectos preocupantes y contradictorios relativos a la celebración del Quinto Centenario y otras cuestiones, las relaciones mejoraron considerablemente, con una mejor voluntad, proyectos más amplios y democráticos, etc. Y eso mientras la expansión económica de España representaba lo que algunos, quizás exagerando, han llamado la segunda conquista española de América Latina, mediante el desarrollo de nuevas iniciativas empresariales de gran alcance no sólo en Cuba sino en toda América Latina.

Para comprender las relaciones entre Europa y América Latina hoy en día, la agenda debería incluir éstos y muchosotros temas. Está también la cuestión del eurocentrismo intelectual, que afecta a las mismas categorías de conocimiento mediante las cuales se estudian los temas, con independencia del lugar de nacimiento de un teórico o pensador concreto. Con todo, lo que me parece más importante subrayar en lo que a nuestras deliberaciones se refiere es que la cuestión de las relaciones euro-latinoamericanas tiene que ver no tanto con la cultural policy, la línea descendiente de fuerza y autoridad, como con la cultural politics, la resistencia de la base por mantener y fraguar espacios y modos culturales. Pese a los romanticismos, y a la existencia de muchas culturas grupales no democráticas, considero a la democratización multicultural un factor crucial para la democratización política y, en último término, económica. Así, suelo centrarme en la gente, en vez de en los espacios nacionales. Lo que me lleva a la noción de que las cuestiones de inmigración y asentamiento reproducen cada vez pautas y problemas más parecidos en América y Europa, y a las formas culturales generadas por esas inmigraciones. En un correo electrónico, la profesora Sandra Ponzanesi anunciaba su conferencia de la siguiente manera: Las crecientes migraciones en masa redefinen a los actores, los lugares y los idiomas de la cultura europea. Dichos cambios culturales se ven magnificados en los textos de cosmopolitas y expatriados, exiliados como todos los emigrantes. Por lo general, los idiomas de los excolonizadores más poderosos (inglés y francés) han sido el medio privilegiado de expresión de naciones, culturas e identidades divididas. Con todo, otras tradiciones emigrantes (como las que se expresan en idiomas excoloniales menores o en lenguas vernáculas) están definiendo nuevos espacios culturales. En los albores del nuevo milenio, es importante evaluar los diferentes orígenes materiales que tiñen dichos textos, y reconocer de qué modo contribuyen a reescribir, expandir y subvertir las nociones existentes de la identida y ciudadanía europeas.

No se trata sólo de los paralelismos entre los trabajadores inmigrados y su impacto en América y Europa, sino también de la emigración económica latinoamericana directa, dispersa por todo el espacio europeo. Aquí surge un paralelismo con la exploración de Mike Davis (2001) sobre la “latinoamericanización” de las ciudades de E.U., en función de la “latinoamericanización” de al menos ciertas dimensionesde la vida cultural europea. Puede fácilmente empezarse por la Península Ibérica, como núcleo evidente de las relaciones euro-latinoamericanas, pero también afecta a Inglaterra y al resto de Europa. En este sentido, los estudios relativos al trabajo doméstico y la prostitución entre la población dominicana de Madrid se integran en la creciente literatura internacional en este ámbito, cuyos ejemplos más destacados no siempre son los mexicanos, portorriqueños u otros en E.U., sino también los trabajadores colombianos en Venezuela, los nicaragüenses en Costa Rica, los ecuatorianos en Italia, etcétera.

Si nos centramos en la cultural politics además de la cultural policy, nos encontraremos con un área de estudio tan fértil como las cuestiones macroeconómicas o políticas. Y nos encontraremos con que muchos grupos latinos (o “hispanos”) de E.U., en su doble preocupación por resistir y establecerse, pueden tener reflexiones importantes que hacer sobre las relaciones euro-latinoamericanas. Aunque no pretendo atribuir a los latinos una función profunda de reserva espiritual de la clase obrera de un gigante de la economía mundial, sí podría realizar una función significativa en relación con la narrativa contemporánea de la modernización en el contexto de la globalización y las transformaciones en América Latina, el Tercer Mundo e, incluso, más allá.