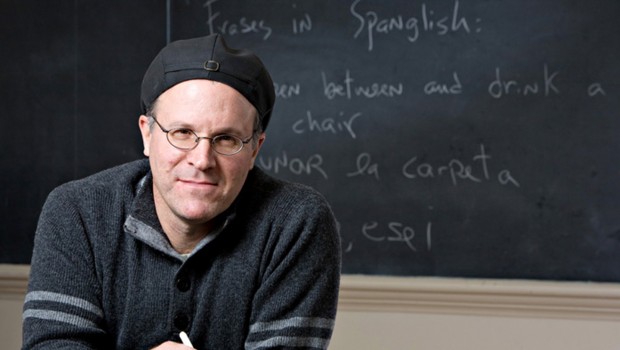

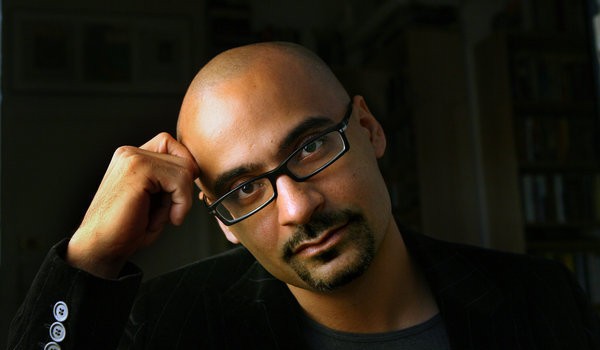

Love and Loss: A Conversation with Ilan Stavans

El amor y la pérdida

Ilan Stavans

VERÓNICA ALBIN: How should one define the word love?

ILAN STAVANS: As a most amorphous human emotion, capable of incorporating extremes: attraction and repulsion, exultation and misery, Eros and Thanatos.

V. A.: In Dictionary Days: A Defining Passion (2005), you devote a brief chapter to the word in different languages: Russian, German, French, Italian, Spanish… Which do you prefer?

I. S.: Phonetically, amor, in Spanish, is the most beautiful. A derivation from the Latin amor. In Greek, eros. The Romance languages play upon the same sounds: amour, amore, amor, l’amor, and, the inspired Romanian variation, iubire. In Medieval German it is lieb, from the Latin libens, connected, as you might suspect, to libido. In any case, I learned about love, physically and emotionally, in Mexico. It is thus fitting that the language of Cervantes would hit closer to my heart.

V. A.: Not Yiddish?

I. S.: For me liebe is a term of endearment toward the community. My upbringing in Mexico in the sixties was defined by a Bundist philosophy, brought by Jews from Eastern Europe, where it fermented at the end of the 19th century. For Bundists the link between people depended on cultural empathy. The others, los otros, was often stressed as the depositories of selfless love.

V. A.: Obviously, your suggestion—and what the chapter in Dictionary Days is about—is that love is understood differently around the globe, depending on the coordinates of time and space.

I. S.: Who can prove that what Cleopatra felt for Antony is the same that Heloise felt for Abelard? For that matter, is it possible to be sure there is any kind of symmetry between what lovers feel for each other? Did Romeo love Juliet the same way Juliet loved Romeo? These are obnoxious questions but they prove our open-endedness toward the concept of love. What is it, really? Might it be studied scientifically? Does it always need to be left to poets to “calibrate” it? Is there a way to measure it?

V. A.: Are poets those who come closest to describing it, then?

I. S.: Sure, and to define it as well. Since love is irritatingly ethereal, you might do better by going to Ovid, Shakespeare, Baudelaire, Christina Rossetti, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Apollinaire, Yeats, Neruda… than to theOED, Larousse, and the Diccionario de autoridades, for instance.

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak; yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

The loved one’s powers in Shakespeare’s poem are earthly, imperfect, human—yet incandescent. No lexicon is able to come remotely close to what love is—its subterfuges, its importunities, its delights—as poems do. Metaphor is love’s niche. Lexicons are too chaste, too prudish. They are bastions against eroticism. Show me a definition able to replicate the incantatory metaphors in Robert Herrick’s famous eulogy “Upon the Nipples of Julia’s Breast”:

Have ye beheld (with much delight)

A red rose peeping through a white?

Or else a cherry (double grac’d)

Within a lily? Centre pac’ed?

Or ever mark’d the pretty beam,

A strawberry shows, half drown’d in cream?

Or seen rich rubies blushing through

A pure smooth pearl, and orient too?

So like to this, nay all the rest,

Is each neat nipple of her breast.

Love doesn’t only change from language to language. It undergoes changes across time too. Our elastic understanding of it today isn’t the same from the one espoused by Plato in the 4th century BCE. Nor is it like courtly love in the Renaissance. Stendhal’s approach to it is different from Proust’s and Freud’s.

V. A.: I Googled the word love. I came up with 500,000,000 hits.

I. S.: In the language of the Internet, the amount is a synonym of infinity. It’s like saying: “I have a million chores to accomplish.” A million is a figure of speech, just like The Thousand and One Nights doesn’t include 1,001 tales. In Arabic, the number means all numbers together.

V. A.: As the polyglot that you are, to which concept of love do you subscribe? Would you describe your views of it as shaped by Hispanic civilization?

I. S.: My wife would probably say yes, but I’m not sure myself. When I was an adolescent, I used to love a la mexicana. I’ve become an American, though. Am I less effusive, more constrained? Maybe so. An immigrant’s journey isn’t qualified in geographical terms: the miles you’ve traveled. Instead, it is about inner transformations. How have you changed since you left the place of origin? In my own case, since 1985, when I moved to the United States, I began a slow yet dramatic process of acculturation. Are there traces of the Ilan Stavans who left Mexico? If so, are those traces still reachable? Do I love nowadays a la gringa?

V. A.: Did Mexican Jews have a style of love of their own?

I. S.: Mimesis is a feature of Jewish life. No sooner do Jews figure out the patterns of a new environment, they quickly incorporate those patterns into their natural behavior. In order to prove themselves authentic, they parade those patterns in ways only an outsider might do. Eventually they become so confident in them they actually start suggesting new patterns for the environment to adopt. Yiddish-speaking immigrants from the Pale of Settlement to Mexico loved the only way they knew how: the European way. Their descendants negotiated a change between the old ways and the new. In the past couple of decades, their grandchildren—the third generation—are opening unforeseen vistas.

V. A.: In On Borrowed Words: A Memoir of Language(2001), you recall your sexual initiation. But the scene isn’t about love, I think. Do you remember the moment you discovered its “extremes,” as you’ve called them: attraction and repulsion, exultation and misery, Eros and Thanatos?

I. S.: For me love and literature have always been interconnected. Years ago, while still in Mexico, I read Denis de Rougemont, in L’Amour et l’Occident in French. It was about how Petrarch, even more than Plato, defined the way Western civilization approaches love. De Rougemont’s style is self-important, grandiose. In any case, I remember reading it just after I had finished Mario Vargas Llosa’s comic novel Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, which is about a semi-incestuous relationship between Marito, the author’s alter ego, and his aunt. At one point Marito says something about Petrarch, something to the effect that he “invented” our views on love.

V. A.: It’s the exact same word you use in Dictionary Days.

I. S.: I was puzzled. Love isn’t an “invention,” like penicillin and electricity. I needed some context. So I read Petrarch’s Canzoniere and, soon after, de Rougemont’s rumination. It was a rather impressionable period in my life. I was eager to understand— to describe rationally—what I was experiencing. You see, around that time I had fallen madly for an older Parisian woman—let me call her “Brigitte”—who had come to Mexico to study. I had been in love before with una niña bien. An inconsequential relationship, in retrospect. It isn’t that I was not in control of myself; the image presupposes the possibility of chaos, i.e., the overriding of all rational thinking. I was under the sign of passion—passion running amok, on the verge of insanity—. Nothing of that was possible with la niña bien. Ours was a conventional liaison, a friendship, really. It was the opposite with Brigitte. Fuego—no other images come quicker to mind—: fire… Every time I was with her, I was shaken by a sense of oceanic emotion, a feeling of being beyond myself, as if I had become part of the cosmos. Do I remember what her mind was like, how she processed thought? Brigitte was intelligent, but that of hers didn’t interest me. It was her body I was hypnotized by: the lines of her profile, the shape of her hair, her minute breasts, the tactile sensation every time I let my hands touch her waist. I couldn’t get enough of her. I sought words to survey my inner landscape. I even challenged myself to write poetry. But I’m no poet… Language for me is an instrument for surveying ideas, not for singing to what Shakespeare, in a superbly baroque twist, referred to as “love’s labour’s lost.”

V. A.: How long did the relationship with Brigitte last?

I. S.: In chronological time, maybe a year. An eternity in existential time. But every night was its own circle of creation. I was ecstatic while those nights lasted. The moment they finished, I was fearful. Anna Akhmatova’s poem about separation, translated from the Russian by Stanley Kunitz, is perfect:

I wring my hands under my dark veil…

‘Why are you pale, what makes you reckless?”

—Because I have made my loved one drunk

With an astringent sadness.

While I lived through the encounters, I recall thinking to myself: I must remember all this in detail. One day I’ll write about it and my only source will be memory.

V. A.: Have you?

I. S.: Not yet.

V. A.: Will you?

I. S.: Maybe you’ve just got me started…

V. A.: Did the readings that occupied you then—Shakespeare, de Rougemont, Petrarch, Vargas Llosa—change your encounters with Brigitte?

I. S.: No, they only intensified them… Literature isn’t therapy. It is not meant to cure. It’s only useful as a form of empathy, making you realize that however unique you might believe to be the door you’re about to cross, others have gone through it before—and left inspired testimony of it.

V. A.: What happened in the end?

I. S.: My descent into madness left a lasting impression. It took me a long time to recover. For years I would see Brigitte in dreams, the Brigitte of the past: svelte, sardonic, tempestuous… I wished I could have kept those images; they had become some sort of sustenance. But not long ago, on a trip to Biarritz, France, I saw her again. She looked different: heavier, more mature, and I did too, of course. The encounter somewhat spoiled the memory. It’s difficult to invoke the Brigitte of the past without superimposing the silhouette I came across in Biarritz. For some reason, she had acquired a copy of de Rougemont’s book in English translation and had saved it for me. I was grateful, of course, but disillusioned. Brigitte was a French part of my Spanish past. I now still saw her, as before, with my metabolism, but my metabolism had now switched to English. I felt an instinctive rejection of the English translation of the book. Furthermore, as I browsed through it I picked up on a number of liberties the translator had taken, beginning with the title: Passion andSociety. I always thought I had been in love with Brigitte. But perhaps I was simply consumed by passion. What is the connection between love and passion? Might one exist without the other?

VERÓNICA ALBIN: ¿Cómo se debe definir la palabra amor?

ILAN STAVANS: Como un sentimiento humano amorfo a lo sumo, capaz de incorporar extremos: afinidad y aversión, júbilo y pesar, Eros y Tánatos.

V. A.: En Dictionary Days: A Defining Passion (2005) dedicas un pequeño capítulo a la palabra en distintos idiomas: ruso, alemán, francés, italiano, español… ¿En qué idioma la prefieres?

I. S.: En cuanto a sonido, amor, en español, es la más eufónica. Derivada del latín amor. En griego, eros. Las lenguas romances se deleitan de una misma musicalidad:l’amour, l’amore, o amor, l’amor y, la variante rumana, iubire, que está colmada de inspiración. En alemán medieval, es lieb, del latín libens, vinculada, como es de esperarse, a libido. De cualquier forma, fue en México donde aprendí sobre el amor, tanto el físico como el emocional. Es por eso que la lengua de Cervantes es la que me brota cuando del corazón se trata.

V. A.: ¿No el iddich?

I. S.: Para mí, liebe es un término para expresar cariño hacia la comunidad. La manera en que me crié en México en los años 60 estaba definida por la filosofía bundista que había florecido a finales del siglo XIX en la Europa oriental y que llegó con los judíos a México. Para los bundistas, el vínculo entre los seres humanos dependía de afinidad cultural. Era sobre los otros donde se vertía el amor desinteresado.

V. A.: Obviamente, lo que estás sugiriendo —y de lo que trata el capítulo en Dictionary Days— es que el concepto del amor no es el mismo en todas partes, sino que está en función de las coordenadas de espacio y tiempo.

I. S.: ¿Quién puede demostrar que lo que sentía Cleopatra por Marco Antonio es lo mismo que lo que sentía Eloísa por Abelardo? Y, ya que en esas andamos, ¿hay manera alguna de estar seguro de que exista simetría entre lo que los dos amantes sienten? ¿Acaso Romeo amó a Julieta de la misma forma en que Julieta amó a Romeo? Son interrogantes molestas pero demuestran que el concepto del amor no tiene nada de hermético. ¿Qué es realmente? ¿Puede estudiarse científicamente? ¿Debemos siempre dejarlo en manos de poetas para ‘calibrarlo’? ¿Hay cómo medirlo?

V. A.: ¿Son entonces los poetas los que lo describen con mayor precisión?

I. S.: Seguro, y son ellos también los que más se aproximan a su definición. Aun así, como el amor es exasperantemente etéreo, correrás con más suerte recurriendo a Ovidio, Shakespeare, Baudelaire, Christina Rossetti, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Apollinaire, Yeats, Neruda… que al Oxford English Dictionary, Larousse o alDiccionario de autoridades, por ejemplo.

Los ojos de mi amada no parecen dos soles,

y el coral es más rojo, que el rojo de sus labios.

Siendo blanca la nieve, sus senos son oscuros,

y si el cabello es negro en ella es hierro negro.

He visto rosas rojas, blancas y adamascadas,

mas nunca en sus mejillas encuentro tales cosas.

Y en algunos perfumes, existe más deleite,

que en ese dulce aliento que emana de mi amada.

Amo escuchar su voz y sin embargo, entiendo,

que la música tiene un sonido más grato.

No he visto caminar por la tierra a una diosa,

pero al andar mi amada, va pisando la tierra.

Mas juro y considero a mi amada tan única,

que no existe en el mundo, ilusión que la iguale.

Los poderes de la amada en el soneto de Shakespeare son terrenales, imperfectos, humanos —mas son incandescentes—. Ningún diccionario puede acercársele siquiera a lo que es el amor —sus malabares, sus importunidades, sus goces— como lo logra la poesía. La metáfora es el nicho donde reside el amor. Los diccionarios son demasiado castos, demasiado pudorosos. Son baluartes contra el erotismo.

El amor no sólo varía de idioma a idioma, sino que cambia también con el paso del tiempo. Nuestra conceptualización elástica del amor no es comparable con la que tenía Platón en el siglo IV AEC. Tampoco puede cotejarse con el amor cortesano renacentista. Asimismo, Stendhal no lo aborda de la misma manera que Proust o Freud.

V. A.: Busqué en Google la palabra amor. Me arrojó 500,000,000 aciertos.

I. S.: En el idioma de Internet, esa cifra es sinónimo de infinidad. Es como decir: “Tengo un millón de cosas que hacer”. Un millón es una figura retórica, de la misma forma en que Las mil y una noches no tiene 1,001 cuentos. En árabe, esa cifra es todas las cifras juntas.

V. A.: Al ser políglota, ¿a qué concepto del amor te adhieres? ¿Considerarías que ves el amor desde una perspectiva del mundo hispánico?

I. S.: Alison, mi mujer, probablemente te diría que sí, pero yo no estoy tan seguro. Cuando era adolescente, quería yo a la mexicana. Pero ahora soy americano. ¿Soy menos efusivo, más medido? Tal vez. La trayectoria del que emigra no debe valorarse en términos geográficos: los kilómetros recorridos. De lo que se trata es de transformaciones internas. ¿Cómo has cambiado desde que dejaste atrás la tierra que te vio nacer? En lo que a mí se refiere, desde que me mudé a Estados Unidos en 1985 me embarqué en un proceso lento pero dramático de aculturación. ¿Quedan rastros del Ilan Stavans que salió de México? De ser así, ¿están aún accesibles dichos rastros? ¿Acaso sé querer ahora sólo a la gringa?

V. A.: Los judíos mexicanos, ¿tenían su manera propia de querer?

I. S.: La mimesis es una característica de la vida judía. Tan pronto los judíos se percatan de los patrones de un nuevo entorno, rápidamente incorporan dichos patrones y pasan a formar parte de su comportamiento natural. Para demostrar que son auténticos, manifiestan esos patrones sólo como lo haría alguien de afuera. Con el paso del tiempo se sienten tan cómodos con ellos que empiezan realmente a sugerir nuevos patrones para que el entorno los adopte. Los inmigrantes de la Europa oriental que hablaban iddich al llegar a México sabían querer como sabían querer: a la europea. Sus descendientes abrieron brecha entre las viejas costumbres y las nuevas. En las últimas dos o tres décadas, sus nietos —la tercera generación— se están abriendo horizontes no previstos.

V. A.: En On Borrowed Words: A Memoir of Language(2001) mencionas tu primera experiencia sexual, tudesquinte, vamos, pues la escena que describes no creo que se trate de amor. ¿Recuerdas el momento cuando descubriste sus “extremos”, como los has denominado: afinidad y aversión, júbilo y pesar, Eros y Tánatos

I. S.: Para mí, el amor y las letras han siempre estado entrelazados. Hace años, cuando estaba aún en México, leí a Denis de Rougemont en L’Amour et l’Occident en francés. Es sobre cómo Petrarca, más todavía que Platón, fue quien definió la manera en que el Occidente aborda el amor. El estilo de de Rougemont es ensimismado, pretencioso. De cualquier forma, recuerdo que lo leí justo después de que había yo terminado la novela cómica de Vargas Llosa La tía Julia y el escribidor, que se trata de una relación pseudoincestuosa entre Marito, el álter ego del autor, y su tía. En algún momento Marito dice algo sobre Petrarca, algo sobre que había “inventado” la manera en que nosotros vemos el amor.

V. A.: Esa es la palabra exacta que usaste en Dictionary Days.

I. S.: Me quedé perplejo. El amor no es un “invento”, como la penicilina o la electricidad. Necesitaba contexto. Así que leí el Canzoniere de Petrarca y, al poco tiempo, las meditaciones de de Rougemont. Estaba yo en un momento de mi vida en que mucho podía influirme. Estaba ansioso por entender —para describir de manera racional— lo que estaba sintiendo. Sabes, es que justo en esa época estaba yo prendado de una parisina mayor que yo —llamémosla “Brigitte”— que estaba estudiando en México. Me había yo enamorado antes de una niña bien. Una relación inconsecuente, ahora que lo miro de lejos. No es que no estuviera yo en control de mis emociones; la imagen presupone la posibilidad del caos, es decir, algo que superaría todo pensamiento racional. Estaba yo bajo el signo de la pasión —pasión descabellada, al borde de la locura—. Nada de eso era posible con la niña bien. La nuestra era una relación convencional, una amistad, realmente. Con Brigitte era lo opuesto. Fuego —no hay ninguna otra imagen que venga tan rápido a la mente—: incendio… cada vez que estaba yo con ella, me veía yo sacudido por una emoción oceánica, una sensación de estar fuera de mí, como si formara yo parte del cosmos. ¿Me acuerdo cómo era su intelecto, como procesaba los pensamientos? Brigitte era inteligente, pero esa parte de su ser no me interesaba. Era su cuerpo lo que me tenía hipnotizado: las líneas de su perfil, la forma de su pelo, sus senos diminutos, la sensación táctil cada vez que mis manos exploraban su cintura. No me cansaba de ella. Busqué palabras para poder hacer un levantamiento de mi topografía interna. Incluso me impuse el reto de escribir poesía. Pero no soy poeta… el lenguaje para mí es un instrumento para examinar ideas, no para cantarle a lo que Shakespeare, en un tropo excelsamente barroco, denominó “love’s labour’s lost”: los trabajos de amor perdidos.

V. A.: ¿Cuánto tiempo duró la relación con Brigitte?

I. S.: En tiempo cronológico, tal vez un año. Una eternidad en tiempo existencial. Pero cada noche consistía en su propio círculo de creación. Mientras esas noches duraron, estaba yo extático. En el momento en que acabaron, tuve pavor. La “Canción desesperada” de Neruda sobre la separación lo invoca a la perfección:

Te ceñiste al dolor, te agarraste al deseo.

Te tumbó la tristeza, todo en ti fue naufragio!

Al vivir la relación, recuerdo haberme dicho: tienes que recordar cada detalle. Un día voy a ponerlo en papel y mi única fuente será la memoria.

V. A.: ¿Lo has hecho?

I. S.: No, todavía no.

V. A.: ¿Lo harás?

I. S.: Creo que me acabas de llenar el tanque de gasolina…

V. A.: Las lecturas que te ocupaban entonces —Shakespeare, de Rougemont, Petrarca, Vargas Llosa— ¿cambiaron tus encuentros con Brigitte?

I. S.: No, sólo los volvieron más intensos… la literatura no es terapia. Su propósito no es curar. Es útil únicamente a manera de empatía, dándote a conocer que aun cuando pienses que el umbral que estás por cruzar es único, otros ya lo han cruzado, y han dejado testimonio elocuente al respecto.

V. A.: ¿Cómo acabó el asunto?

I. S.: Mi caída en la locura me dejó marcado. Me tomó mucho tiempo recuperarme. Durante años veía yo a Brigitte en sueños, la Brigitte del pasado: esbelta, sardónica, tempestuosa… deseaba haber podido retener esas imágenes; se habían transformado en un tipo de sustento. Pero no hace mucho, en un viaje a Biarritz, Francia, la volví a ver. Se veía distinta: un poco más de peso, de más madurez, y yo también, claro. El reencuentro empañó mis recuerdos. Me es difícil invocar la Brigitte del pasado sin superponerle la silueta que encontré en Biarritz. Por alguna razón, ella había adquirido una copia del libro de de Rougemont en traducción al inglés y lo había guardado para dármelo. Le estaba agradecido, por supuesto, pero desilusionado. Brigitte era una parte en francés de mi parte en español. Aún la podía yo ver, como en antaño, con mi metabolismo, pero mi metabolismo ahora veía en inglés. Sentí un rechazo instintivo a la traducción en inglés del libro. Además, cuando lo estaba ojeando, me percaté de varias licencias que se había tomado el traductor, empezando por el título: Passion and Society. Siempre había yo pensado que estuve enamorado de Brigitte. Pero tal vez estaba yo consumido por la pasión. ¿Cuál es la relación entre el amor y la pasión? ¿Puede el uno existir independientemente del otro?

Can you publish more articles about this subject? I’d care to find out more details.