MARIO VARGAS LLOSA on Capricorn 1985-1991

Fernando Castro R.

In the spring of 1985, the Rice University Department of Spanish and Portuguese invited Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa to deliver two lectures: “The culture of freedom” and “The total novel.” I seem to recollect the first one was a diatribe against gadgets and communication via iconic symbols. David Sobrevilla, my advisor and philosophy professor at the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Lima, had introduced me to Vargas Llosa at a retrospective exhibition of works by Fernando de Szyszlo –one of his closest friends. Although he probably did not remember me from that brief encounter, I did remember from our conversation that he admired Max Ernst. The first time Vargas Llosa came to Houston, the museum that Renzo Peano designed and that currently houses the Menil Collection did not yet exist. However, I knew from Ileana Marcoulesco —whose work at the International Circle for Research in Philosophy was funded by the Menil Foundation— that their collection included several impressive Ernst works.

I asked Ileana, who was very close to Mrs. Dominique de Menil, if it would be feasible to have Vargas Llosa visit Mrs. D’s home so he could meet her and view the collection. I shared my ploy with María Teresa de Leal, chairperson of Rice’s Spanish and Portuguese Department. María Teresa liked the idea and asked to be included in the plan if it materialized. Ileana Marcoulesco was an extremely well-read person and quite aware that Vargas Llosa was likely to be the next Nobel laureate in literature. She made the arrangements. Unfortunately, Mrs. D was in New York and Ileana was unable to join us on account of a previous commitment. Needless to say, Vargas Llosa and his wife Patricia were delighted with the idea of this very exclusive tour.

In view of the fact that my graduate-student voiture (an old but sporty two-door Opel Manta that often refused to start) was unfit to drive VIP’s around, I recruited my friend Helen Runnels, whose Saab was more up to the task and whose enthusiasm for Latin American literature made her jump at the opportunity. On a Saturday morning, we picked Mario Vargas Llosa, his wife Patricia, and María Teresa from the Warwick Hotel (now Hotel Zaza) and drove to River Oaks. Susan Meng, an aide to Mrs. D, was waiting for us at the main entrance of the Philip Johnson house on San Felipe Avenue. I suspect Ms. Meng had not the faintest idea of who Vargas Llosa was, but she welcomed us very politely anyway and had Mario sign the guestbook. Helen and I observed discreetly as Mario signed the heavy book. I believe María Teresa signed it as well.

Ms. Meng noticed my camera and gently urged me not to take any photographs in the house because “Mrs. de Menil is a very private person and she is very concerned about people taking pictures of her home. She worries that they may be used inappropriately.” I explained that I had only brought the camera to have a memento of our visit but that if it made her feel uncomfortable, I would keep it in my bag. So I did, and she proceeded to take us on a tour around the house. María Teresa, Mario, Patricia, and I shared a fascination with the understated splendor of the house and its contents. It was not ostentatious, yet it was elegant and majestic in its modern international style. No matter where you looked you were possessed by the power of artworks. I don’t remember exactly which works we saw; my memory confuses them with what I have later seen at the Menil Collection museum. I may be wrong, but I am almost positive we saw Magritte’s L’Evidence éternelle, Malevich’s Suprematist Composition, Ernst’s Retour de La Belle Jardinière, Lam’s La Visitante and Klein’s MG7, among others.

Mario Vargas Llosa, Patricia Vargas Llosa, Helen Runnells, María Teresa Leal, Ms. Meng (Mrs. de Menil`s assistant), Mrs. de Menil and Max Ernst sculpture: “Capricornio” ©Fernando Castro.

When we finished touring the house, Ms. Meng led us to the back garden where Capricorn, a huge sculpture by Max Ernst, stood facing the house. It represented an authority figure with an infant on its lap and a mermaid sitting next to it. The characters seemed to be stalking the house and/or demanding that its dwellers come out to confront them. Unexpectedly, Mrs. D’s aide graciously acceded to my taking pictures in the garden as long as I promised not to publish them without their knowledge and consent. I took about twenty pictures; some of them snapshots and some, posed portraits. In one of them I shot Vargas Llosa sitting on the lap of the main figure. After we left Mrs. D’s home we all went to have lunch at a Brazilian restaurant in the Montrose area that María Teresa had recommended. A week later, I mailed Vargas Llosa a few prints of the pictures I had taken.

On November of 1987, after losing a protracted legal battle to get a permanent resident visa, I returned to Peru in order to fulfill my Fulbright fellowship requirement to share in my country of origin whatever knowledge I had gained at Rice. A lot had changed during my eight-year absence. The Aprista regime of President Alan García was in office thanks to a second-round election in which the Peruvian Right voted for him in order to prevent the Leftist candidate, Alfonso Barrantes, from winning. My mother had bought an apartment in a high-rise building called Chateau Gabriella in Miraflores. Even though it was smaller than the Residencial San Felipe apartment we used to live in, it was definitely more exclusive. Doris Gibson, the owner of Caretas magazine, lived in the penthouse. My bedroom window faced Avenida Pardo and between the tall Miraflores buildings I could even get a tiny glimpse of the Pacific Ocean.

One sunny summer morning when I was buying a copy of Caretas in the kiosk across the street from Ramiro Llona’s studio, he peered out of the window and invited me up. I enjoyed walking into the controlled chaos of his studio to see how his new work was evolving. As we were chatting and enjoying some fresh figs, I skimmed through the issue of Caretas I had just purchased. I almost choked on a fig when I saw in utter astonishment the picture I had taken in Houston of Vargas Llosa sitting on the regal lap of Capricorn. To my disgust, the picture had not been credited. To my dismay, a promise had been broken. With that photograph, in that issue of Caretas, Mario Vargas Llosa publicly launched his candidacy for the presidency of Peru. From that moment on, direct communication with him for anybody outside his close-knit circle became nearly impossible.

Mario Vargas Llosa sitting on Marx Ernst´s work ©Fernando Castro

In vain I tried to reach him by phone. I rode my bicycle over to his Barranco house in the hope of seeing him. The whole block was cordoned-off by regular policemen and private security, and I had to approach cautiously. It was not an exaggeration. Peru was under siege by Shining Path and MRTA terrorists, and Vargas Llosa –by announcing his candidacy and his neo-liberal platform– had written himself into their hit list. Moreover, the government itself could not be trusted with his safety. I drew near the armed security men while raising my left hand and holding an envelope in the fingertips of my right. “¡Buenos días! I just want to deliver a letter to Mr. Vargas Llosa.” One of the security guards, who was carrying an assault rifle, approached me to take the envelope. In spite of having personally delivered the letter, I feared it would never reach him. So I decided to send a message via Blanca Varela, a renowned Peruvian poet and close friend of Vargas Llosa.

Two weeks later while I was hosting a small soirée with friends at my mother’s apartment, the phone rang. It was Mario Vargas Llosa. He greeted me affectionately and apologized for the publication of the photograph. He explained to me that he was in Spain when Caretas asked for a picture. “When my secretary was looking through my files, she found your magnificent photo at the Menil house and she thought it ideal, and so did the people of Caretas who decided to use it.” I reminded him of the promise under which we had been allowed to take the picture. He told me not to worry and if a problem ever arose, he offered to assume total responsibility. Having cleared that issue, I congratulated him for his brave decision to become a presidential candidate, given that he had everything to lose and little to win. Nonetheless, I added that in my modest opinion he was allying himself with parties that were political fossils in Peru. After a brief silence he responded that in politics one often has to be pragmatic and make some concessions in order to…

That was the last time I ever spoke with Mario Vargas Llosa. Up to the very week of the elections, the polls overwhelmingly indicated he would be the winner. I voted for him not out of admiration for his writing, but because I believed he had correctly assessed the needs of Peru at that time. First, it was necessary to do away with terrorism in order to bring normalcy back to daily life and reassure investors. One way to do that was to arm and support the peasantry against the terrorists, but I was not sure whether any of the candidates was willing to do it. Secondly, Peruvians needed a fair and free chance at producing wealth for themselves and creating jobs for others (a position endorsed by economist Hernando de Soto and by some people on the Peruvian Left). In Peru, only a few wealthy industrialists thrived because of special privileges granted by the state. There were too many bureaucrats and few taxpayers, so the former needed to be substantially reduced and the latter, increased. Lastly, middle-class limeños were in denial about the state of war with the terrorists and they needed to be actively on the offensive. The ruling Aprista party was utterly corrupt and incapable of undertaking any of these changes. Indeed, it was causing as much damage to the country as the terrorists of Shining Path.

©Fernando Castro

The end of that story is that Vargas Llosa lost the elections and shortly thereafter, drifted more and more towards dogmatic neo-liberalism (not in the U.S. sense of “liberalism,” but in the free-market sense of the term, à la Milton Friedman). As a result of his presidential adventure he did not lose his livelihood in any sense, but he lost me. I still read his fiction with enthusiasm, but except for his anti-nationalism, I have built up a resistance to many of his other political views and the gratuitous attacks he and his son Alvaro have launched against the Left. Both altruism and prudence as self-interest have more entrenched and illustrious roots in our philosophical and political thinking than their writings reflect.

It was not clear in 1990 what kind of president Alberto Fujimori, Vargas Llosa’s unexpected political nemesis, would turn out be. He was elected during a second round thanks to the joint opposition to Vargas Llosa of the Apristas, the Left, and even some people on the Right who never felt comfortable with him. The only thing most people knew about Fujimori was that he was an engineer and that he had been dean of the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina. The first difference between the two candidates was an audible one: while Vargas Llosa’s spoken Spanish was flawless, Fujimori, in spite of his academic credentials, spoke Spanish with a horrendous syntax. However, one thing that made me proud of the Peruvian electorate is that –in spite of some racial slurs from some media moguls aimed at Fujimori– they did elect a man who was ethnically different from most of them.

During the Aprista regime of Alan García (1985-1990), Donna (my former American wife) and I had humorously endured the scarcity of cooking oil, rice, sugar, and other basic foods. We had learned to cope with hyperinflation by buying dollars. We had learned to see our way through bureaucracy by means of bribery and clout. We had nervously survived earthquakes and about a dozen terrorist bombs within a ten-block radius of our home. We had gotten used to blackouts and climbing seven flights of stairs to our apartment. In 1990, I even survived typhoid fever. Nevertheless, the joy of living in Peru and the warmth of our friendships made it all worthwhile. Our son Fabián was born in Lima on January of 1990. As a birth present Ramiro Llona gave him a beautiful print of his most recent work (it still dominates my living room). In the summer of 1991, a cholera epidemic in Lima that spread out of control brutally exposed the ineptitude and fragility of our institutions. We took this new threat as the cue for us to leave Peru. Seven months after Fujimori became president of Peru, Donna, Fabián and I emigrated to the United States.

1992

Although some religious people and psychoanalysts claim there are no accidents, during my three-year stay in Peru, almost accidentally, I became an art critic and curator. But that is a different story. In the spring of 1992 I was already settled in Houston. As a result of my accidental career change, I came to co-curate the photography exhibit “Modernity in the Southern Andes: Peruvian Photography 1900-1930” which was shown in Houston during the Fotofest 1992 biennial. In addition to curating that exhibit, I had several other responsibilities. I was the main organizer of a Colloquium on Research of Latin American Photography and a Workshop on Conservation of Photographic Archives that was given at the Menil Collection. For the historical 500th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival on this continent commemorated in the year 1992, the exhibition space at the Brown Convention Center was divided in two halves. One side housed the European exhibits, the other, the Latin American exhibits. Thus, the directors of the biennial –Fred Baldwin and Wendy Watriss– attempted to obliquely allude to the fateful encounter between the two continents, although any mention of 1492 was omitted from the official literature for reasons of political correctness, and possibly of cordiality with sponsors.

One of the many events at Fotofest that year was the adjudication of an award to the exhibit “Photography at the Bauhaus” by Leica, the German camera manufacturer. The ceremony took place at the Brown Convention Center before an audience of Fotofest VIPs that included museum curators, directors, artists, critics and members of the media. Even before that ceremony had ended, Henry Brimmer, who at the time was the publisher of Photometro magazine of San Francisco, came up to talk to me. As much as he admired the Bauhaus, he considered it had received enough recognition, while our exhibit, which he judged to be the best at Fotofest ’92, had been unduly relegated to second tier. “Unfortunately,” I said, with a bit of humorous reticence, “there is no Latin American camera manufacturer.” “Well, maybe there isn’t,” he said drawing a malicious smile, “but there is a Photometro.” He turned suddenly and left in a hurry.

The following day, after a long day of colloquium, workshop, and problem management, I was ready to go home. Over the loudspeaker of the Brown Convention Center I was summoned to our exhibit site. There, in a quasi-private ceremony with Fred Baldwin, Wendy Watriss, my co-curators, Peter Yenne, Edward Ranney, and our collaborators, Adelma Benavente, Jonathan Schwartz, Fernando La Rosa, and Anamaria McCarthy, Henry handed me a diploma titled “ACIEL Award” (“Leica” spelled backwards) for curatorial excellence. Perhaps it was a merely symbolic gesture, but I appreciated it as much as if it were a Nobel Prize.

That evening I returned to my Banks street apartment very tired and half-starved but glowing with pride. As soon as I opened the door my toddler rushed to hug me, and my wife Donna told me to call Mrs. Dominique de Menil —right away. She had left her private phone number. Had something gone awfully wrong at the conservation workshop in the Menil museum? I telephoned immediately and Mrs. D herself answered. She told me she had heard wonderful things about the exhibit I had curated and wondered if I could personally tour her through it. I thanked her and said it would be an honor to do so. “When would you like to see the exhibit?” “Well, are you busy now?” she asked. “No,” I said. “Will you pick me up in half an hour?” “Certainly.” She dictated her address to me, but I did not need to write it down.

©Fernando Castro

I took a one-minute shower and in five, I was heading towards the River Oaks house that —unbeknownst to Mrs. D— I had visited seven years before. When I rang, she opened the door herself and was ready to go. By now I had learned that Mrs. D was not like other wealthy people. She did not need luxurious adornments on her person in order to shine. Her elegance, like that of her home, was subdued and low-key. So I had no second thoughts about asking her to climb aboard my humble ten-year-old Toyota Corolla. On the way downtown, she asked about the exhibit and I informed her about the cultural and historical background of the images. Hoping she would be inclined to help with the rescue efforts of The Photographic Archive Project, a non-profit organization I had helped found, I told her about the precarious conditions of photographic archives throughout Latin America; the almost heroic way in which we put the exhibit together, bringing the fragile glass negatives all the way from Peru, receiving small donations from private individuals who were moved by the force of the images, working all night to finish printing five days before the opening, etc. She listened quietly and was pleased to learn that the Menil Collection had hosted the workshop on conservation of photographic archives. On my part, I felt I was talking too much like a used-car salesman, so I left it at that.

It was foggy and cool at the Brown Convention Center in downtown Houston. Mrs. D, a shawl resting over her shoulders, walked slowly through the show. I walked beside her, speaking only when it was appropriate. She stopped in front of Crisanto Cabrera’s picture of a peasant family posing for a portrait with their sheep. I explained to her that up to the 1920’s, the wool trade was very profitable in Peru. Most indigenous peoples raised alpacas for wool, whereas landowners of European descent raised merino sheep. So for the family in the portrait the sheep were a status symbol —a symbol of being more like Europeans than like Native Americans; the irony being that alpaca actually produces finer wool. She also wanted to know more about Martin Chambi’s photograph of people drinking chicha (a corn-brew) and playing sapo, a game where players win if they can throw a coin into the open mouth of a bronze frog. “How curious,” Mrs. D said, “I remember members of my family playing this game in the south of France.”

Once we finished viewing the Peruvian exhibit, we toured Flor Garduño’s exhibit, “Witnesses of Time.” Mrs. D was deeply moved by what she called the “spirituality” of the images. I was about to show her Mario Cravo Neto’s and Luis González Palma’s exhibits when –touching her forehead with the tips of her fingers– she said she could not absorb any more. “It’s going to take me a couple of days to take in all of this,” she smiled, rolling her eyes slightly and spinning her head. For a second, I flashed back to the day –almost twenty years before– when we had lunch together during a colloquium on ethnicity at the Rothko Chapel. Of course, she did not recognize me as that irreverent young man who told her she was misinformed, and I did not feel it pertinent to remind us both of one of the most embarrassing moments of my life. Although I was armed with a camera, I did not take any pictures of her during our time together.

At about nine in the evening, we drove under a chilly drizzle across an almost deserted downtown back to River Oaks. I decided to come clean with Mrs. D at least on one score. “You know, Mrs. Menil, this is not the first time I have visited your home,” I said, after a moment of guarded silence. “Oh?” she said looking at me a bit mystified. I proceeded to tell her the whole Vargas Llosa story, cover photo in Caretas for his presidential campaign and all. As I narrated, off and on I watched her facial expression in order to veer my story towards fiction if it became necessary. Happily, she seemed to be enjoying the story so much that I rewarded her with a true account. Once I finished telling it, she said, “So, Mario Vargas Llosa was at my home and I did not even know it! I would’ve liked to meet him.”

When we returned to her home, Mrs. D asked me to come in and sign her guest book. The next day, when I confided with Ileana Marcoulesco that she had asked me to do so, Ileana said, “Don’t make too much of it. She asks everybody to sign her guest book.” I had been foolishly fantasizing that it was a privilege reserved to Nobel nominees and ACIEL recipients!*

***

*If there ever was a memoir that deserved a footnote, this one is it. This essay was written mostly in January 1998, a few days after Dominique de Menil (1908-1997) passed away. Mario Vargas Llosa had not yet been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature at that point. He received it in 2010. In 2015, Vargas Llosa separated from his wife Patricia after a fifty-year marriage. A more complete version of this essay, as well as all the photographs I took of Mario Vargas Llosa at the Menil’s home and at the onset of his presidential campaign are in the archives of the Menil Collection.

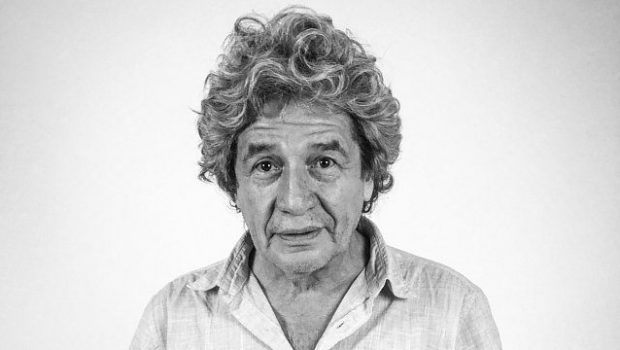

*These previously unpublished images were taken by Fernando Castro. Cover image: Fernando Castro and Mario Vargas Llosa next to Ernst´s sculpture

Fernando Castro is an artist, critic and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University as a Fulbright scholar. He is a member of the art board of FotoFest and of the advisory board of the Houston Center for Photoography. He is a contributing editor of Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal, and Spot. Last year he delivered the lecture “Elian” at the University of Cambridge, England.

Fernando Castro is an artist, critic and curator. He studied philosophy at Rice University as a Fulbright scholar. He is a member of the art board of FotoFest and of the advisory board of the Houston Center for Photoography. He is a contributing editor of Aperture Magazine, Art-Nexus, Literal, and Spot. Last year he delivered the lecture “Elian” at the University of Cambridge, England.

Posted: August 24, 2015 at 10:48 pm