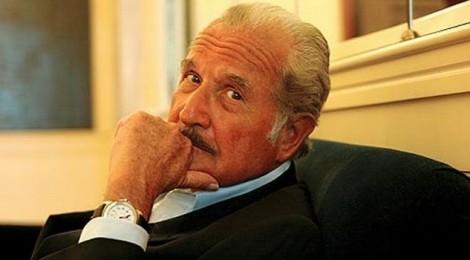

Carlos Fuentes: Mexico Needs an Overhaul

México necesita una reforma a fondo

Rose Mary Salum

This year, the Inprint Margaret Root Brown Reading Series celebrates its 30th anniversary. Since its inception, the program has presented writers recognized with the Nobel, Pulitzer and Booker Prizes, as well as the National Book Award. Carlos Fuentes was featured as part of the 2010- 2011 program, dedicated to the world’s best contemporary writers, giving Literal, Latin American Voices the opportunity to hold a conversation with him.

* * *

Rose Mary Salum: In 2010, Vlad was published. Why the vampire theme?

Carlos Fuentes: This was before the theme became fashionable. I used to watch vampire movies when I was a child. Bela Lugosi would give me a terrible fright whenever I saw him. So I said, Dracula the Vampire is always hanging out in Europe. When is he coming to America? Well, he came in to New Orleans in the Tom Cruise movie, but he’s never come to Mexico. Perhaps because he would be competing with too many local vampires… it’s terrible. But he finally came to Mexico and settled down there, under the name of Vlad.

RMS: The vampire metaphor seems very powerful to me. This act of blood-sucking has become very meaningful since 2008.

CF: As far as blood sucking is concerned: they’ve been doing it to us our entire lives.

RMS: As an editor and writer living in the United States, it concerns me that not enough books are being translated. In your opinion, what’s going on?

CF: What’s going on is that this country, the United States, has become very provincial. When I started out, my editors, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, were publishing Francois Mauriac, Alberto Moravia, and ten or fifteen foreign novelists. Now there’s no one. Those of us who have been established for a long time, like Gabriel García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, or myself, have kept on publishing, but almost out of condescendence. There is no interest in new writers, in the vast quantity and quality of writers we have in Hispanic Ameirca. This country has become very self- absorbed and preoccupied, and it still does not understand what is going on in the world. Barack Obama, who is a great president, is trying to tell Americans, “We are not alone, we are not the only ones,” but it is very hard for them to accept that the era of the United States is over.

RMS: And perhaps this has to do with deteriorating standards of education…

CF: They have deteriorated terribly; education is no longer the priority it once was. But above all, the issue is how the United States sees itself in relation to the rest of the world.

RMS: You have spoken countless times about the Baroque, in your book The Buried Mirror you discuss the theme and your literary style is strongly influenced by it.

CF: The Baroque is a vital theme in Mexican history, a Baroque that was a sensual response to Catholicism and Protestantism. The New World Baroque became a mode of expression for mulattoes and blacks in the community. The approach toward the Baroque is different in Latin America than in Europe. But then came the Enlightenment, with Voltaire and all the thinkers from that era, and the nation attempted to modernize following the lead of the United States. We wanted to be what we cannot be. The ejido or community ownership concept was destroyed in favor of private property, because that was what modernity demanded. In literature, the Baroque is a way to resuscitate the totality of the past. We are not progressive or linear, we are circular and confusing, and we wish to continue to be so.

RMS: What has been the influence of Faulkner on your work?

CF: We have a saying: Latin American literature began in Mississippi.

RMS: In your books, you have explored the issue of violence in Mexico. Today, when one speaks of violence, one inevitably speaks of illegal narcotics. I know that you form part of the commission to legalize drugs. Up until now, what has stopped us from legalizing them?

CF: First of all, if we are talking about violence, the violence in Mexico is historic, political, and revolutionary. This is the first time that crime is the origin of such considerable violence. The theme is not limited to Mexico; it is global, and it can only be resolved globally. Holland has decriminalized and now the entire world goes there to take drugs. Mexico is next-door neighbor to the United States, and what we can do depends on the gringos. So, if this is not discussed in a global fashion, it will be extremely difficult to attack the problem. Presidents Cardoso, Gaviria and Zedillo have made this point very well.

RMS: But for the time being, the only viable solution is legalization.

CF: Yes, but there is an ideal of liberty that is only an illusion: it consists of everyone doing whatever they want, and it just isn’t so. Because in the end, the drugs cross the Mexican border, and where they end up, who manipulates them, who is making the money, is a mystery. Of that we know absolutely nothing, it’s almost as if there were a conspiracy of silence regarding the destination of drugs. We know who the Mexican drug lords are, we know what goes on in Ciudad Juárez, but once the drugs go across, we know nothing. It would be an information challenge for all of you to discover what happens after the drugs enter the United States.

RMS: So the responsibility is ours.

CF: It is also yours.

RMS: I have always thought that education is a fundamental issue not only in Mexico, but around the world. Yet in Mexico today, aside from the fact that we lack the kind of education we had under Vasconcelos in the 1920s or Torres Bodet in the 1940s, a proposal of that caliber simply doesn’t exist.

CF: No, it doesn’t, but it should. Education is the foundation for everything. Productivity, generation of wealth: it all depends on the quality of education. Vasconcelos understood this very well. The great leap Mexico made from 80% illiteracy in 1920 was because Vasconcelos’s campaign was tremendously effective in creating that awareness. An awareness that has been lost, and must be reawakened. Now that we have reached a population of 110 million, education must be revisited as the basis for development. Without education, there can be no development.

RMS: Especially now that young people are graduating but they have no opportunities, so they go into organized crime.

CF: They go wherever they can, if there aren’t any opportunities. What Mexico needs is in- depth reform. A new Social Contract, one might say, to take advantage of the country’s enormous strength. We have 60 million young people in Mexico, but what are they to do? Will they go into crime, become jobless, or find gainful employment? We must offer and organize job opportunities.

RMS: Currently do we have the means for a Torres Bodet, a Vasconcelos, to exist?

CF: Of course we do, the country is very wealthy, it has marvelous people. The political situation has simply prevented all the wealth the country possesses from manifesting itself. We have a three-way particracy. Politicians fight amongst themselves, they say things in Congress, and then they say the opposite, but there is no ordered program. A program for the future that says we are going to seriously rescue education. We are going to create a country capable of confronting the problems Mexico faces instead of continuing to dodge them, or come up with partial solutions. Until the present we have relied on tourism, oil. We have become overly dependent on tourism, oil, and laborers’ remittances. Now we need to rely on the Mexican workforce. That is the great Mexican Revolution.

RMS: Motivating production?

CF: Why not, given the amount of work we have before us? We have hard-working, marvelous, intelligent people. Caramba! We are falling short.

RMS: Not long ago, during the Bicentennial, we reflected on centuries past in Mexico: in 1810 there was Independence, in 1910, a Revolution, and now, in 2010, the drug problem.

CF: Don’t be a prophet, now, don’t start foretelling things you shouldn’t (laughter).

RMS: But it’s as if wild Mexico never went away.

CF: Wild Mexico has never gone away. Sometimes it calms down, it dissimulates, but in the end it manifests itself when there are no political solutions. But there ought to be, so that wild Mexico can be creatively channeled.

RMS: Immigration is a deeply complex problem. There are divergent ways of thinking about this. What is yours?

CF: It is a problem that can be viewed from different angles. In the first place, Mexicans come to this country because they are needed. They do the work that many Americans won’t. I wish they would stay in Mexico, because we need them there. We don’t have the workers we need to renew the country, to rebuild the infrastructure. We have to do what we can to keep them from going, because we need them. But once they reach the United States, they should be treated as workers, because that is what they are. Not criminals, or illegal aliens. This has also become a global problem and should be settled globally. This has got to change, because these workers are needed in Mexico, just as they are needed in the United States. This country cannot function without them.

RMS: But so little has been done from this side to make that change happen.

CF: Federal laws are needed. Here they have what I call Arizonitis. But a federal immigration law is required.

RMS: And the obligatory question: what projects do you have for the future?

CF: I won’t discuss those, because if I do, they’ll be frustrated…

Rose Mary Salum is the founder and director of Literal, Latin American Voices. She´s the author of Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) among other titles.

Rose Mary Salum is the founder and director of Literal, Latin American Voices. She´s the author of Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) among other titles.

©Literal Publishing

Este año, Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series celebra su 30 aniversario. A lo largo de su trayectoria han presentado escritores reconocidos por el Nobel, Pulitzer, National Book Awards y Broker Prize. Dentro de su programa del 2010-2011, dedicado a los mejores escritores contemporáneos, se presentó Carlos Fuentes con quien Literal. Latin American Voices tuvo la oportunidad de conversar.

* * *

Rose Mary Salum: En este 2010 salió publicado Vlad. ¿Por qué el tema de los vampiros?

Carlos Fuentes: Fue antes de que se pusiera de moda; yo veía películas de vampiros cuando era chico. Bela Lugosi me impresionaba terriblemente. Y me dije: el vampiro Drácula siempre anda en Europa, ¿a qué hora viene a América? Bueno, vino con la película de Brad Pitt a Nueva Orleáns, pero a México nunca había llegado. Quizá porque tenemos muchos vampiros locales de competencia… Es terrible. Pero por fin llegó a México, se instaló y es Vlad.

RMS: Me parece que la metáfora del vampiro es muy rica. Este asunto de estar chupando la sangre dice mucho a partir del 2008.

CF: De chuparnos la sangre, nos la han chupado toda la vida.

RMS: Como editora y escritora viviendo en Estados Unidos veo con preocupación que no se traducen suficientes obras. En su opinión, ¿qué está sucediendo?

CF: Lo que ha pasado es que este país, Estados Unidos, se ha vuelto muy provinciano. Cuando yo empecé a publicar, mi editorial (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) editaba a Francois Mauriac, Alberto Moravia, a diez o quince novelistas extranjeros. Ahora no se publica a nadie. Los que nos instalamos hace mucho, como Gabriel García Marquez, Vargas Llosa o yo, seguimos apareciendo pero casi como una condescendencia. Pero no hay interés en los escritores nuevos, en esta enorme cantidad y calidad de escritores que tenemos en Hispanoamérica. Este país se ha vuelto muy ombliguista y preocupado consigo mismo, y sigue sin entender lo que pasa en el mundo. Un gran presidente como Barak Obama está tratando de decirle a los Estados Unidos: no estamos solos, no somos los únicos. Pero a los americanos les cuesta mucho aceptar que la era de Estados Unidos se acabó.

RMS: Y quizá tenga que ver que el nivel de educación ha decaído.

CF: Ha decaído muchísimo, la educación ya no es una prioridad como en otros tiempos. Pero el problema está, sobre todo, en cómo se ve Estados Unidos en su relación con resto del mundo.

RMS: Usted ha hablado infinidad de veces sobre el barroco –El espejo enterrado es un ejemplo– y su estilo está fuertemente influido por él.

CF: El barroco es importantísimo en nuestra historia porque surgió como una respuesta sensual al catolicismo y al protestantismo. El barroco del nuevo mundo se volvió así la vía de expresión de los mulatos y negros de la comunidad. Sin embargo, a la llegada de la Ilustración (con Voltaire y todos los pensadores de la época) nuestra nación buscó modernizarse a imagen de Estados Unidos. Quisimos ser lo que no podíamos ser. Se destruyó el concepto del ejido, por ejemplo, en favor de la propiedad privada porque eso era lo que la modernidad pedía. En la literatura, el barroco es la forma de resucitar la totalidad del pasado. No somos progresivos ni lineares: somos circulares, confusos –y queremos seguir siendo eso…

RMS: ¿Cuál ha sido la influencia de Faulkner en su trabajo?

CF: Siempre dijimos que la literatura Latinoamericana empezaba en Mississippi.

RMS: En sus libros ha abordado el problema de la violencia de México. Actualmente, cuando uno habla de esto no puede evitar el tema de las drogas. Sé que pertenece a la comisión para despenalizarlas. Hasta el momento, ¿qué ha detenido dicha legalización?

CF: Si se habla de violencia, la de México había sido histórica, política y revolucionaria. Hoy es la primera ocasión en que una violencia tan grande como la que sufrimos tiene su origen en el crimen. Pero el tema no es particular de México, es global y sólo se resolverá globalmente. México es vecino de Estados Unidos y lo que podamos hacer depende de esta relación. Repito: si no se propone de manera global, va a ser muy difícil atacar el problema. Los presidentes Cardoso, Gaviria y Zedillo lo han planteado bien.

RMS: La única solución viable hasta el momento es la legalización.

CF: Sí, pero existe una ilusión, un ideal de libertad que perimitiría a cada cuál hacer lo que quiera, pero eso no es posible. Porque, finalmente, la droga cruza la frontera mexicana y a dónde va a dar, quién la manipula, quién gana dinero. Misterio. De eso no se sabe ni una palabra, como si existiera una conspiración de silencio en torno de todo esto. Sabemos quiénes son los capos mexicanos, sabemos qué pasa en Ciudad Juárez, pero una vez que la droga cruza, no sabemos nada. Sería una cuestión que aquí deberían averiguar: qué es lo que sucede cuando la droga entra a Estados Unidos.

RMS: Entonces la responsabilidad es nuestra.

CF: También.

RMS: La educación es un asunto fundamental, no sólo en México sino en todo el mundo. Pero en México, donde bajamos del nivel educativo que teníamos con Vasconcelos en los años veintes o con Torres Bodet en los cuarenta, no existe una propuesta que esté a la altura de nuestras necesidades.

CF: No, no la hay pero debe haberla. La educación es la base de todo. La productividad, la riqueza, el desarrollo: todo va a depender de la calidad de la educación. Esto lo entendió Vasconcelos muy bien. El gran salto que dio México cuando tenía un 80% de iletrados en 1920, es porque la campaña de Vasconcelos fue tremendamente eficaz para crear conciencia. Esta conciencia se ha perdido y hay que resucitarla. Ahora que somos 110 millones de habitantes hay que retomar la educación como base del desarrollo. Sin educación, no hay desarrollo.

RMS: Los jóvenes que hoy se gradúan no tienen oportunidades e ingresan al crimen organizado.

CF: Si no hay oportunidades se van a donde pueden. México necesita una reforma a fondo. Un nuevo Contrato Social, diría yo, para aprovechar la enorme fuerza del país. Tenemos 60 millones de jóvenes en México. ¿Qué van a hacer estos jóvenes? ¿Se van a ir al crimen y al desempleo o van a acceder a un trabajo productivo? Hay que ofrecer y organizar esa oferta de trabajo.

RMS: ¿Existen las vías para que haya un Torres Bodet, un Vasconcelos?

CF: Claro que sí, el país es muy rico, tiene gente estupenda. Simplemente la situación política ha impedido que se manifieste toda la riqueza que tiene el país. Tenemos una partidocracia dividida en tres. Se pelean entre sí, están en el congreso, dicen cosas y luego lo contrario pero no hay un programa ordenado. Un programa a futuro que diga: vamos a rescatar y educar seriamente. Vamos a crear un país capaz de enfrentar los problemas que tiene México y no irlos esquivado y encontrando soluciones parciales. Hasta el momento hemos contado demasiado con el turismo, el petróleo y las remesas de los trabajadores fuera del país. Ahora hay que contar con el trabajo de los mexicanos. Esa es la gran Revolución Mexicana.

RMS: Motivar la producción.

CF: Cómo no, la cantidad de trabajo que tenemos por delante. Tenemos gente trabajadora, estupenda, inteligente. ¡Caramba! Estamos desaprovechando.

RMS: El bicentenario nos ofreció la ocasión para reflexionar sobre dos siglos de México. En 1810 vivimos la Independencia. En 1910, la Revolución Mexicana. Y ahora, en el 2010, tenemos el problema de las drogas.

CF: No sea usted profeta, no ande profetizando cosas que no debe (risas).

RMS: Pero es como si el México bronco no hubiera desaparecido.

CF: El México bronco nunca ha desaparecido. A veces se calma, disimula, pero finalmente se manifiesta si no hay soluciones políticas. Debe haberlas para que el México bronco se canalice creativamente.

RMS: La inmigración es un problema profundamente complicado. Existen diversas vertientes de pensamiento al respecto. ¿Cuál es la suya?

CF: Este es un problema que se puede tratar desde distintos ángulos. En primer lugar los mexicanos llegan a este país, Estados Unidos, porque son necesarios: hacen el trabajo que muchos americanos no. Yo desearía que se quedaran en México, nos hacen falta en México. No tenemos a los trabajadores que necesitamos en el país para renovarlo, para reconstruir nuestra infraestructura. Tenemos que hacer lo que podamos para detener su salida porque también los necesitamos. Pero cuando llegan a Estados Unidos, deben ser tratados como trabajadores, porque eso es lo que son. No criminales e ilegales. Todo esto se ha vuelto un problema global también y tiene que resolverse a nivel global. Esto debe cambiar porque esos trabajadores se necesitan en México, de la misma forma que se necesitan en Estados Unidos. Este país no podría funcionar sin ellos.

RMS: Pero se ha hecho tan poco de este lado para lograr el cambio.

CF: Se necesitan leyes federales. Aquí tienen lo que yo llamo Arizonitis. Pero se necesita una ley federal sobre la inmigración.

RMS: La pregunta obligada, qué proyectos tiene para el futuro.

CF: De eso no hablo porque si lo digo se me frustran…

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto 2015) y Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing 2013) entre otros títulos.. Su twitter @rosemarysalum

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto 2015) y Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing 2013) entre otros títulos.. Su twitter @rosemarysalum

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.