On Peace

Políticas para la paz

Rob Riemen

After two devastating conflicts, Europe was able to agree on one matter: no more war. Democracy, economic growth, equal rights, freedom of expression, education, health care and social justice were embraced as core values to be cherished in order to pave the way to reconciliation, in hopes that no war would ever take place again. In this conversation with critical thinkers. The Nexus Institute invited thirteen of the foremost politicians, diplomats, historians, philosophers and critical thinkers to discuss these stimulating and important questions . Rob Riemen, Director of the Nexus Institute, leaded a discussion with many of the, about peace and how to perserve it under the auspices of the organization’s War and Peace conference. (This conference has been edited for content and length.)

***

Rob Riemen during the inauguration of the conferences Image © Jelmer de Haas

Rob Riemen: Why is it that we always have to be dreamers when it comes to peace? What’s so difficult about having a peaceful society?

Robert Cooper: Because it’s unnatural. The natural condition of man is to fight. War is the natural condition, peace the unnatural. Peace requires effort, constant work.

RR: Is this the general view around the table? Or is there a little bit more optimism?

Michael Ignatieff: I think every time you have the successful maintenance of peace, and to this degree I would agree with Robert, it’s an enormous victory, and it’s important always to remember why it matters. There’s a sense increasingly in North America and Europe that it’s futile to intervene in other people’s conflicts and try to stop them. It’s worth remembering, for example, that Macedonia did not explode and was not sucked into the Balkan vortex simply because of preventive deployment by the United States Marines. Believe me, my solution to world peace is not the preventive deployment of Marines everywhere. I’m just saying that every time we stop war from happening, we win an important victory. Most of all for our own belief that there is an independent world, and that we have responsibilities to this world. Futility, the sense that it is hopeless, the sense that they will fight and there is nothing we can do, seems to me much more of a problem than imagining peace.

Hassan Mneimneh: We can think of war as the expression of excess fear and greed that is at the core of the human being and a driver of civilization. We seem to be in a continuous effort throughout history to manage that excess. But I agree, throughout history we have not succeeded for many reasons, some of which are structural. When there is a serious imbalance in material facts, it is difficult to convince people that the state of affairs has to be driven towards further balance. Another reason, which I think is very important, is that we have yet to establish a permanent system of universal values. We are still living in the illusion that we have developed over the past two centuries, that there is an agreement about underlying values. Therefore, talking about values assumes there is a framework of reference that everyone can refer to and benefit from, when in fact I think we are at a point where we may have lost the universal.

RR: We have had peace in Europe for the last seventy years. This is not the case in the Middle East at this moment. What can the Middle East learn from Europe?

Avishai Margalit: It is clear that Yugoslavia, for you, is not Europe. I think that what actually changes is the nature of war, not the nature of peace. Most wars are civil wars. With intervention sometimes, but the main reality of wars is that they are civil. Now, civil wars take on average six years, and between states they average three months. The bitterness and cruelty and narcissism of minor differences in wars, the intensity of it, is enormous because everything is at stake in a civil war; who we are, how we define ourselves. Therefore, our main worry should be civil wars, rather than the old talk about administrating the world at large and talking in grand terms about wars and about peace. It’s the philosophical disease of talking about nothing in particular.

RR: You wrote On Compromise, which became very influential book, in which you argue that to establish peace, you do not necessarily need justice.

Avishai Margalit: Peace and justice are not fish and chips, they are not necessarily complementary commodities. They can be in tension. And the tension between peace and justice is there, and sometimes you have to compromise on justice in order to get peace, that is the claim. This is not to say you should not address other worries, the point is that you cannot solve all of them because there is an inherent tension between peace and justice. In many places, if you want justice to prevail in a strong sense, it means an ongoing conflict, because you won’t satisfy the demands of justice that the parties perceive.

Michael Ignatieff: Part of the reason why peace is an ambiguous good and part of why people fight is because they don’t want peace, they want justice all the way. The difficulty about conflict is that it is connected to the deepest, most urgent values we have, and people will not trade justice for peace. People choose war not for irrational reasons or because they can’t see the virtue of peace, but because there are things that matter much more to them than peace, things like justice or retribution, vengeance. These are deep human realities.

RR: If Hassan is right, if the only way out of civil wars is to rediscover what our universal values are, then what should we do?

Avishai Margalit: In order to be able to converse, to talk to one another, we have to accept the notion that we do not have a common frame of reference by necessity. We seem to have over the past two centuries, particularly with regards to the creation of international order, convinced ourselves that it is implicit there. The changing nature of war—first to civil and then beyond to non-state actors, who actually are engaged in war with states, such as Al Qaeda, a tiny bunch engaged in a global war—has not been mirrored by a change in our understanding of a framework, of an international network from a legal point of view, but also from a philosophical, ethical, and moral point of view.

Avishai Margalit. Image by Jelmer de Haas

Michael Ignatieff: I was amazed, Robert, that you said that Europe has been at peace for seventy years. I think one of the issues is not only that war has changed, but that our sense of peace has changed. The proposition that Europe has been at peace for seventy years misses Yugoslavia. But it also misses that are at least two people that could not join this audience this afternoon because of what happened July 17th. Every person in this country, of all countries, is now aware that the distance between zones of safety, where there is supposedly peace, and zones of danger can collapse at 30,000 feet in one instant. And the second thing is that every time you go through Schiphol airport, you are in a security zone. And we are now used to these zones of safety that we live in transferring, little by little, powers to governments that used to only be transferred in war time. The third element of our changing experience of war is that it’s all about Maskirovka, in which war is masked. Putin is engaged in territorial invasion of a European state and says, “I am doing no such thing. There is no war in Eastern Ukraine.” Or “I am protecting populations in Eastern Ukraine.” We live in a world in which we are being lied to about war, in which war comes to us in an instant when we’re flying in an airplane, and in which over the last fifteen years, we’ve become a State that has transferred powers to liberal democracies that only used to be exerted in wartime. So the sense that peace and war have begun to change their shape and why that matters is relevant. If you have to rouse a European public or a Canadian public or a North American public to face a threat in eastern Ukraine, you have an enormous difficulty convincing people that they are in fact at war. It makes the politics of mobilizing firm, decisive action extremely difficult, because “we are at peace, we are not in danger.” In fact, in a molecular way, we don’t live in peace, and we should sense an integral feeling of threat about what is happening in Eastern Ukraine but do not. Because of what I would call Maskirovka, the nature of war itself.

Lila Azam Zangan: I think something did happen in old Europe. Our most prominent living philosopher in Iran is a man called Daryush Shayegan. He wrote a book in French called La lumière vient de l’Occident, which means “enlightenment comes from the West”. He was being slightly provocative, of course, but I think we keep on forgetting that something happened in the 18th century in Europe, there was a definition and an idea of man. This definition was the flower, the burgeon of democracy and the way we still think about the body politic today. As a person of the younger generation, I keep wanting to go back to that idea of man. I want to try and extract us from this state of exception, from relativism that says, “well, we can do that because in the end, our values are greater, and you know, we have different values and maybe we don’t understand each other,” and we must change the barometer of values. I think the real challenge for peace is to believe in a universal value. And I do. And I think that’s the connection that we are here to make today between a universal value created somewhere in Europe in the 18th century and the nexus with culture and imagination. With something that we as private citizens, but also as writers, actors, musicians, and politicians, may work toward every day and every moment.

RR: Avishai, do you think it’s possible to go back to the 18th century?

Avishai Margalit: There is nothing wrong with cosmopolitics, but there is no politics in cosmopolitics. Namely, that there are no institutions that really can govern the world as such. Therefore, it’s still an international world. States are here to stay for a long time, and actually, the reason why people out here are so worried about Ukraine is in order to keep the lines intact, no matter whether there are Russians in east Ukraine or not, or whether they speak Russian in east Ukraine, people think that blurring the lines is dangerous and even inherently believe these lines should be sacred. Because people are afraid of challenging the nature of internationalism. So “cosmopolitan” is obviously a noble emotion, but just emitting the right emotions won’t do the trick here, because the boundaries are still there, and the main problem, as I said, is that within those boundaries are civil wars.

Michael Ignatieff: I think the question that Avishai is posing is, what is the politics of peace?

Robert Cooper: Because the politics of peace are always particular. There is no general theory of peace. You have to solve each problem one by one, and on the whole, I’m not sure I agree with what you said earlier, Michael. Because of course, everybody wants justice, and of course what they mean by justice is always different, but they will never get it through war. Because once the wars begin, the injustices multiply, and the bitternesses multiply. So the first thing is not to begin. And that’s why whatever you do, even with Ukraine at the moment, where there is a war going on (it’s not a civil war), even there, we should go slowly, because every step you take leads you a little bit deeper into a conflict, and once it begins, it’s much more difficult to finish it. So let’s move slowly, let’s threaten, let’s be ready to act, but actually acting? One should be really cautious about that.

Michael Ignatieff: When one thinks about a politics of peace in this situation, I guess what I say first of all is that it’s really important to strip away the illusions about living in peace over seventy years and realize the sense in which there is an ongoing threat to the post-war order. That is, a border has been altered by force. So the first element in the politics of peace is simple realism, facing facts. The facts are that a border has been changed without the consent of the people who live in it. And the second illusion which is even more deeply embedded and is an obstacle to a politics of peace was some idea about globalization meaning convergence. There was some idea after 1989, because of international trade and globalization, because we all use the same gadgets, because we are all in the same information space, and because there is a rising middle class everywhere and everybody is benefitting, all boats are rising, that there is a general convergence and that creates the economics of peace. Well, I think one of the things that the Ukraine story is telling us is that globalization produced a great deal of economic convergence in the sense that Russia and China look like some kind of State capitalist society, but of political convergence there has been none. And also, just to pick a fight, I teach human rights for a living, that’s what I do. And I teach it to students from eighty countries. The only way I can teach human rights, that is, the vindication of the 18th century values Lila holds dear, is by understanding that it’s a bloody argument from dawn till dusk. They simply don’t agree about the terms of universalism, and I actually think that people who hold rather common views about universal values can fight each other to the death, and that is a reality we need to understand as well, unfortunately.

RR: Is the European Union a civilizing global force which can spread global peace?

Robert Cooper: It would be nice if this were true. But I think the answer to that is, not yet. Two reasons: first of all, the first thing to understand if you want an answer to the question about the seventy years of peace in Western Europe, because there was not peace in Eastern Europe, the reason was America. It was not just the Marshall Plan, actually the European Union was as much an American creation as a Franco-German creation. It wouldn’t have happened without America, specifically without Dean Acheson and many other people. It needed American backing. The contribution of NATO to peace in Europe is not just that it maybe kept the Soviets out, but that it produced a transparency in military affairs that you never had before. It meant that normally Germany, facing on the one side Russia, needs to have a gigantic army, in case it needs to face both Russia and France together, and NATO made that unnecessary. It produced transparency in military affairs across Europe, it produced military cooperation rather than competition, and this together with the creation of the European Union, none of this would have happened without the USA. For that seventy years’ peace, we have above all to thank the United States. Now, I think this era is coming to an end, not because the USA is leaving, but because the focus is shifting to Asia. The inclination to, some would say, happily invade the Middle East is less than it was before, and we Europeans have a lot of problems in our neighborhood of which Ukraine is high on the list, but if you look at north Africa, the Sahel, what lies behind it in countries like Nigeria: we have a lot of problems, most of which are too small for America. We were lucky with the Soviet Union, because this was a global scale problem, and the US felt it was a problem for the USA, and the problems that Europe now faces are regional problems, much more than global problems, and America I am sure will help, but Europe will have to do more.

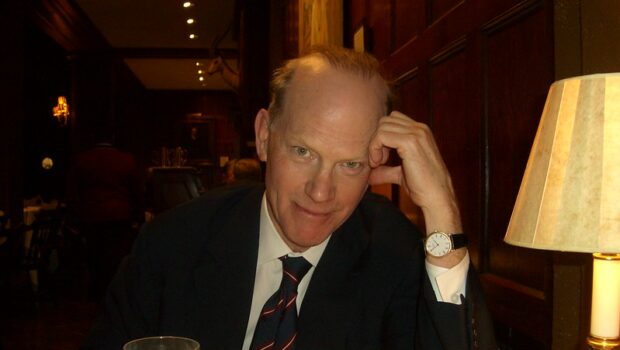

Michael Ignatieff. Image by Jelmer de Haas

Michael Ignatieff: To pick up something Avishai said earlier about the enormous explosion of intrastate war, the decline of war between states and the increase of war within states, is the phenomenon of post-imperial state formation. And we are not finished. The Arab-Israeli conflict in some sense can be seen as post-imperial state formation. In 1945, we had forty-five nations in the United Nations, and we now have a hundred and ninety-five. For my money, that’s one of the great victories for humanity, actually, because it means that millions of people who were ruled by others now rule themselves. Sometimes not so well, sometimes with internal conflict, but if you ask what you want for a world that would be more peaceful, you want a world of responsible states, of responsible and capable sovereigns who deliver minimum amounts of political space to religious ethnic and other social minorities. I think it’s a matter of rejoicing that China is not the cowed, humiliated power that it was in 1900 and is no longer under the insane Communist tyranny of Mao. I look around a world in which African nations are growing incredibly strongly, and countries like Ghana are having democratic successions that are peaceful. I just say that there are many forces actually making for peace, and one of the most basic is the consolidation of post-imperial state order. And the rise of a multipolar world. So then the challenge of peace becomes how we accept and live with pluralism. I mean how we accept the fact that there are going to be in China or Russia stable, consolidated authoritarian regimes that do not buy some of the universals. They are responsible if they do not make war on other states. And if they do not genocidally massacre their own people. My criteria for responsibility is minimal: they don’t kill other people, and they don’t kill their own. Then the question is how to have a global order in which you have authoritarian regimes that are not a menace to their neighbors, and that’s what is being tested at the moment. If we can get there, that’s a really good thing. The world we’ve lived in for the past seventy years is a better world than the world that we inherited in the ruins of 1945.

RR: Freud is on your side, no less. Einstein asked him, “Why war? You are a big psychological genius, explain it to me,” and he literally writes, “We may rest on the assurance that whatever makes for cultural development is also working against war.” This is almost a politically incorrect view, but it relates to what you argue, Lila, or to your idealism that with books, with literature, we can make a difference. Why do you think that?

Lila Azam Zangan: I remember reading one of my favorite books, Memoirs of Hadrian by Yourcenar, which was on your reading list. And she talks about the Emperor Hadrian, whom she idealizes a bit: when somebody disagreed with him, as apparently one of his secretaries did, he sent off a stone tablet on his head and killed him. He was also a bit of a tyrant, nobody is perfect. He was an emperor. But he really tried. And he came to a difficult end in Israel, in the Bar Kokhba revolt in Palestine, Israel, and so somebody who really sought to be a pacifier in the end, in a way, failed. And perhaps we are bound to fail, but does it matter? Because the reason why I love Yourcenar so much is that one point, she puts it in his mind that we’ve had so much strife, so many wars. And of course our internal, our own private spaces and private lives are ridden with wars such as malady, unrequited love, old age, death. Yet he says that because of culture, because of those victories, because even of love, we have moments of immortality. And to me, that is why I believe in culture.

Robert Cooper: This is very nice. But I have to admit, if we were to say what we believe in, I believe in politics. Because I don’t like them very much at the moment, we seem to live in a period of great mediocrity. But maybe it always seems like that. But nevertheless, if you are talking about war and peace, you need to solve problems with people. You need to find compromises, you need to talk to people, you need to understand people, you need cultural understanding as well, and empathy. All of those things you need but in the end you also need persistence in simply looking for compromises. I have a quotation which is not from Blake or from Tolstoy. It’s actually from another Russian. Who writes at one point, “We are pulling at two ends of a rope. And in the middle of the rope is tied a knot which is called war. And the harder we pull, the tighter the knot becomes. And at some point, the knot may become so tight that even those who have tied it cannot untie it. Now if you want to know the name of the Russian, it was Nikita Khrushchev. He is writing a letter to President Kennedy in the course of the Cuban missile crisis. For me this is a powerful image of actually what you need to do to make peace. You need to relax. To stop pulling on the rope. To give somebody a chance to untie the knot. To me, that’s the image. You get peace when you stop pulling the rope, when you start talking.

Robert Cooper. Imahe by Jelmer de Haas

Horia Roman Patapievici: That’s all very true. But I would like to add another dimension. I will quote a story about Muhammad. He went to fight some minor fight. When he was back, he said to one of his friends, “Well, this was a small war, now let’s dedicate ourselves to the great war. And the great war was the inner war. And the dimension I want to add, not bagatalizing what we are discussing here about life and death, peace and war, is that each of us have a inner dimension and we are now fighting this kind of inner war. We try to achieve peace, and it was an ideal of all ancient philosophies. They wanted to find the equality of mind or soul. They wanted to achieve ataraxia, which is being unpassionate. And why was that so important? Because soul was important, the inner dimension of man, and because the idea was that the inner reality is not peace, it is war. The sage must acquire the contrary of what is natural, which is war. The contrary to war was the pacification of mind or of soul. And of course there is a connection between what people are doing starting from their thoughts, and we believe that having good thoughts leads to a good life and to a non-violent life. If we were in ancient Rome, or in ancient Greece or Athens, I think we would have started with this inner war.

Avishai Margalit: When you hear people say, “I’m a realist,” you usually find a delusional nut. Then people talk about the inner self and you get another kind of nuttiness. The issue is here not between the realists or non-realists. The issue is how to address seriously the problem of implementing peace in places where there is a war. Now, a great deal of concentration is about peace agreements. But the main problem is not peace agreements, but the implementation of peace. Who will finance the peace, who will look after the security of the people after their war, when the armed forces become violent gangs? The main worry, I think, for the European is that there are millions of people on the move as refugees out of those civil wars. Those are really serious problems to address before we address our interiority.

Michael Ignatieff: There is a weary fatalism the world is going to hell in a handcart which is an obstacle to practical political action, and there is a kind of global thing we just have to shake ourselves out of. The world is complicated, it is not necessarily getting better, but it has changed enormously since 1945. The other point is about partiality, you said that tribal partiality is inevitable. This takes us to the virtue of universal values, human rights for example. I think the thing to be said in favor of universal values is the constant normative discipline of tribal partiality. That’s the purpose of it. You never overcome the fact that you care about your citizens, your family, your loved ones more. But the universal values are there to say wait a minute, you are wearing blinkers. And that, it seems to me, to the degree that universal values have a function, I think they do have a political function.

Images: © Jelmer de Haas

Our special thanks to The Nexus Institute

Rob Riemen (1962) is Founder, President & CEO of the Nexus Institute, Founder & Editor of Nexus, an journal of essays for cultural philosophy, is a writer and cultural philosopher. He is the author of Nobility of Spirit.

Rob Riemen (1962) is Founder, President & CEO of the Nexus Institute, Founder & Editor of Nexus, an journal of essays for cultural philosophy, is a writer and cultural philosopher. He is the author of Nobility of Spirit.

Traducción David Medina Portillo

Sólo tras dos conflictos devastadores Europa fue capaz de ponerse de acuerdo sobre la siguiente cuestión: ni una guerra más. La democracia, el crecimiento económico, la igualdad de derechos, la libertad de expresión, la educación, la salud y la justicia social se acogieron entonces como valores fundamentales con el propósito de allanar el camino de la reconciliación y con la esperanza de conjurar cualquier otra posibilidad de guerra. En la siguiente charla Rob Riemen, director del Nexus Institute, conversa con destacados intelectuales en torno de la paz y las maneras de preservarla. Dicha plática se llevó a cabo en el contexto de la Nexus Conference bajo el título War and Peace. [Dada su extensión, la transcripción original de esta charla ha sido editada].

***

Rob Riemen inaugurando la conferencia. Imágenes de © Jelmer de Haas

Rob Riemen: ¿Por qué siempre tenemos que ser unos dreamers en cuanto se habla de paz? ¿Es tan difícil contar con una sociedad pacífica?

Robert Cooper: Porque es antinatural. La condición del hombre es la disputa: la guerra es su condición natural y la paz resulta antinatural. Requiere esfuerzo, trabajo constante.

RR: ¿Es esta la visión general de la mesa o existe al menos un poco de optimismo?

Michael Ignatieff: Cada vez que tienes éxito en el mantenimiento de la paz —y en este punto estoy de acuerdo con Robert— es una enorme victoria y, por lo mismo, es importante recordar siempre por qué esto es trascendente. En Estados Unidos y Europa existe cada vez más la sensación de que es inútil intervenir en los conflictos de la gente y tratar de detenerlos. Vale la pena recordar, por ejemplo, que Macedonia no explotó ni fue engullida por el vórtice balcánico debido al simple despliegue preventivo de los Marines norteamericanos. Y créanme: mi solución no está fincada sobre este despliegue preventivo de los Marines por todo el orbe en favor de la paz mundial. Sólo estoy señalando que cada vez que conjuramos una guerra obtenemos una victoria importante. Sobre todo por nuestra propia creencia de que existe un mundo independiente sobre el que tenemos responsabilidades. La futilidad y ausencia de expectativas, el sentimiento de que habrá violencia y no hay nada que podamos hacer al respecto, me parecen un mayor problema que imaginar la paz.

Marines norteamericanos

Hassan Mneimneh: Podemos pensar en la guerra como la expresión de un miedo excesivo y, por otra parte, de la ambición que está en el corazón del ser humano y es un espoleador de la civilización. En cualquier momento de la historia mostramos este mismo esfuerzo por contener dicho exceso. Pero estoy de acuerdo: a lo largo de esa misma historia y por múltiples motivos —algunos de ellos estructurales—, no lo hemos logrado. Cuando existe un serio desequilibrio en términos materiales es difícil convencer a la gente de que deben encaminar la situación hacia en remoto equilibrio. Otra razón —muy importante a mi parecer— es que todavía debemos edificar un sistema de valores universales. Aún vivimos en la ilusión, desarrollada durante los dos siglos anteriores, de que existe un pacto en torno de valores subyacentes. Por lo mismo, se asume la existencia de un marco de referencia al que cada uno puede remitirse benéficamente cuando, de hecho, pienso que hemos llegado a un punto en donde quizá hemos perdido lo universal.

RR: En Europa hemos mantenido la paz durante los pasados setenta años. No es el caso del Medio Oriente en la actualidad. ¿Qué se puede aprender de Europa?

Avishai Margalit: Es claro que para usted Yugoslavia no es Europa. Creo que, en realidad, lo que cambia es la naturaleza de la guerra, no la de la paz. La mayoría de las guerras son civiles, con intervención externa a veces aunque lo primordial es que sean civiles. Ahora bien, este tipo de guerras duran en promedio seis años y, en cambio, los conflictos entre estados tres meses. La crudeza, la crueldad y el narcisismo de los pequeños diferendos en las guerras y la intensidad de todos ellos son enormes porque todo está en juego en una guerra civil: quiénes somos y cómo nos definimos a nosotros mismos. En consecuencia, nuestra preocupación principal debería concentrarse en las guerras civiles antes que en la vieja charla sobre la administración del mundo en general y el parloteo grandilocuente sobre las guerras y la paz. Esta es la enfermedad filosófica de discurrir sobre nada en particular.

Avishai Margalit. Imagen de Jelmer de Haas

RR. Usted escribió On Compromise, que se convirtió en un libro muy influyente y en el cual afirma que para establecer la paz no se requiere necesariamente la justicia.

AM: La paz y la justicia no son como el pescado y las papas fritas, productos no necesariamente complementarios. Estos pueden hallarse en tensión. La tensión entre la paz y la justicia persiste y, a veces, debes renunciar a la justicia con el fin de conseguir la paz porque ese es el reclamo. Ello no significa la imposibilidad de abordar otras preocupaciones pero el punto es que no se pueden resolver todas éstas porque existe una tensión congénita entre la paz y la justicia. En muchos lugares, si se desea que prevalezca la justicia en un sentido fuerte, eso implica un conflicto en curso porque usted no va a satisfacer las exigencias de justicia de todas los involucrados.

Michael Ignatieff: En parte, una de las razones de por qué la paz es un bien ambiguo y de por qué la gente lucha, radica en que dicha gente no quiere la paz sino que anhela cierta justicia a toda costa. La dificultad de este tipo de conflictos es que están conectados a nuestros valores más profundos y apremiantes. Y la gente no va a negociar justicia a cambio de paz. Elige la guerra no por razones irracionales o porque no pueda ver las virtudes de la paz sino porque existen para ellos cosas que importan mucho más que la paz; cosas como la justicia o la venganza, por ejemplo. Se trata de realidades humanas muy profundas.

RR: Si Hassan tiene razón, si la única manera de salir de las guerras civiles es redescubrir nuestros valores universales, ¿qué debemos hacer entonces?

Avishai Margalit: Con el fin de ser capaces de conversar, de hablar el uno con el otro, debemos aceptar la idea de que no contamos necesariamente con un marco de referencia común. Sobre todo en lo que respecta a la creación de un orden internacional, en los dos siglos pasados parecemos habernos convencido de que ese orden estaba implícito. La naturaleza cambiante de la guerra —primero civiles y luego entre actores no estatales que, en realidad, se dedican a la guerra con los Estados, como Al Qaeda, un pequeño grupo involucrado en una guerra global— no se ha reflejado en nuestra comprensión de un marco, de una red internacional desde el punto de vista jurídico pero también filosófico, ético y moral.

Michael Ignatieff: Me asombra, Robert, que diga usted que Europa ha estado en paz durante setenta años. Creo que uno de los problemas no es sólo que la guerra ha cambiado sino que nuestra percepción de la paz también se ha modificado. La idea de que Europa ha estado en paz durante setenta años omite a Yugoslavia. Pero también omite que al menos dos personas no pudieron llegar a este auditorio por lo acontecido el 17 de julio [con el vuelo MH17 de Malaysia Airlines derribado por un misil en territorio ucraniano]. Cada persona de este país (de todos los países) es consciente ahora de que la distancia entre las zonas de seguridad —donde suponemos que existe la paz— y las zonas de peligro, puede colapsar a 30.000 pies en un instante. Otra cuestión es que siempre que usted vaya de paso por el aeropuerto de Schiphol se encuentran en una zona de seguridad. Ahora estamos acostumbrados a estas zonas de seguridad en las que vivimos al transferir, poco a poco, poderes a los gobiernos que antes sólo se podían ceder en tiempo de guerra. El tercer elemento que ha cambiado de nuestra experiencia de la guerra es que todo es una suerte de maskirovka [ocultación] que enmascara nuestros conflictos. Putin está empeñado en la invasión de un Estado europeo y, sin embargo, afirma: “No hay guerra en el este de Ucrania”, [sólo] “estoy protegiendo a esa población”. Vivimos en un mundo en el que mentimos acerca de la guerra, en el que ésta nos alcanza mientras volamos en un avión y en el que —durante los últimos quince años— nos hemos convertido en un Estado que ha cedido poderes a las democracias liberales que antes sólo podían ser ejercidos en tiempos de guerra. Así que la percepción de que la la guerra y la paz están cambiando de forma y que ese hecho es de suma importancia resulta pertinente. Si usted tiene que animar a un público europeo, canadiense o norteamericano a afrontar una amenaza en el Este de Ucrania, tendrá serias dificultades para convencer a la gente de que esa región está efectivamente en guerra.

Ello hace de la política de la movilización firme y de la acción decisiva algo extremadamente difícil puesto que… “estamos en paz, no en peligro”. De hecho y en una forma molecular, no vivimos en paz y deberíamos percibir una sensación integral de amenaza a propósito de lo que pasa al Este de Ucrania, aunque no lo hacemos debido a lo que he denominado como maskirovka [ocultación], la naturaleza misma de la guerra.

Lila Azam Zangan: Creo que algo tuvo su origen en la vieja Europa. Nuestro filósofo vivo más prominente en Irán es Daryush Shayegan, quien escribió un libro en francés titulado La lumière vient de l’Occident, que traducido significa “la luz viene de Occidente”. Quiso ser un tanto provocativo, por supuesto, pero creo que seguimos olvidando que algo sucedió realmente en el siglo XVIII en Europa, cuando había una definición y una idea del hombre. Esta definición fue el florecer, el brote de la democracia y la forma con la que aún pensamos el cuerpo político de nuestros días. Como alguien de una generación más joven, mantengo el deseo de retornar a esa idea del hombre. Quisiera que intentemos alejarnos de este estado de excepción, del relativismo que dice “nuestro conjunto de valores es amplio porque, usted sabe, tenemos valores diferentes y tal vez no nos entendamos entre sí” y debemos cambiar de barómetro. Pienso que el verdadero desafío para la paz es creer en un valor universal. Considero asimismo que esa es la conexión que debemos establecer, hoy y aquí, entre un valor universal creado en algún punto de Europa en el siglo XVIII y sus vínculos con la cultura y la imaginación. Se trata de algo en lo que podemos trabajar día con día y a cada momento como ciudadanos pero también como escritores, actores, músicos o políticos.

RR: Avishai, ¿cree que es posible volver al siglo XVIII?

Avishai Margalit: No hay nada de malo en la cosmopolítica pero no hay política en ella. Esto es, no hay instituciones que realmente puede gobernar al mundo como tal. En consecuencia, sigue siendo un mundo internacional… Los Estados llegaron aquí para quedarse mucho tiempo y, de hecho, la razón por lo que la gente está muy preocupada por Ucrania es en demanda de mantener intactas las líneas de frontera, no importa si hay rusos en el Este o no, o si en esa región hablan ruso: la gente piensa que borrar esos límites es peligroso e, incluso, creen tácitamente que dichas líneas deben ser sagradas. La gente tiene miedo de desafiar la naturaleza del internacionalismo. Así que “cosmopolita” es una emoción noble, desde luego, pero la sola emisión de las emociones correctas no operará ningún truco aquí debido a que los límites aún se mantienen y el principal problema, como he dicho, es que dentro de esos límites suceden las guerras civiles.

Michael Ignatieff: Me parece que la pregunta que Avishai está planteando es dónde está nuestra política de la paz.

Robert Cooper: Las políticas para la paz son siempre particulares. No existe una teoría general de la paz: se debe resolver caso por caso. Y en términos generales no estoy seguro de estar de acuerdo con lo que dijiste antes, Michael. Porque, obviamente, todo mundo quiere justicia y lo que entienden por justicia siempre será diferente, pero nunca obtendrán nada mediante la guerra. Una vez que ésta da inicio las injusticias y el rencor se multiplican. Así que lo primordial es evitar su irrupción. Y es por eso que cualquier cosa que hagas —incluso en el actual caso de Ucrania, donde hay un conflicto en marcha pero que no es una guerra civil—, hay que ir poco a poco ya que cada paso que des te hunde un poco más en el problema y, una vez que éste comienza, es mucho más difícil mitigarlo. ¿Procederemos con cautela, vamos a ser persuasivos y a estar listos para actuar realmente? Uno debe ser muy cauteloso.

Michael Ignatieff: Cuando uno piensa en una política para la paz en situaciones similares creo que es realmente importante despejar las ilusiones acerca de una supuesta paz de más de setenta años y caer en la cuenta de que hay una amenaza en curso al orden de posguerra. Es decir, existe una frontera que ha sido alterada por la fuerza. Así que el primer elemento en una política para la paz consiste en el realismo simple de enfrentar los hechos. Y los hechos son que esa frontera ha sido modificada sin el consentimiento de las personas que viven en ella. La segunda ilusión —aún más arraigada como obstáculo para una política de paz— ha sido la idea de que la globalización significaba convergencia. Después de 1989 existió esa concepción debido al comercio internacional y a una globalización en la que todos utilizamos los mismos gadgets porque todos participamos del mismo espacio de información e, igualmente, porque existe una ascendente clase media en todas partes y todo el mundo se beneficia de que exista una convergencia general que crea una economía de paz. Bueno, una de las cosas que la historia de Ucrania nos está indicando es que la globalización produjo una enorme convergencia económica en el sentido de que Rusia y China constituyen sociedades con algún tipo de capitalismo de Estado, sin embargo, entre ellas no se ha dado convergencia política de ningún tipo. Y también y sólo para comenzar a discutir, yo enseño derechos humanos para ganarme la vida, eso es lo que hago. Imparto clases a estudiantes de ochenta países y la única manera en la que se puede enseñar derechos humanos, esto es, la reivindicación de los valores del siglo XVIII que Lila Azam Zangan sostiene, es mediante la comprensión de que se trata de un argumento sanguinario de principio a fin. Sencillamente no están de acuerdo sobre los términos de este universalismo y, de hecho, creo que las personas que coinciden habitualmente sobre valores universales pueden luchar entre sí hasta la muerte. Esta es una realidad que, por desgracias, tenemos que entender.

Robert Cooper. Imahen de Jelmer de Haas

Robert Cooper: Lo primero que uno debe entender es que si buscamos una respuesta a la cuestión sobre los setenta años de paz en Europa occidental (porque no existe paz en Europa del Este), la razón fue Estados Unidos. No era sólo el Plan Marshall; en realidad, la Unión Europea fue tanto una creación norteamericana como franco-alemana. Y no habría sido posible sin Estados Unidos y, específicamente, sin Dean Acheson y otras tantas personas. Se necesitaba el respaldo de Estados Unidos. La contribución de la OTAN a la paz en Europa no es sólo que quizá contuvo a los soviéticos sino que produjo una transparencia en asuntos militares como nunca antes. Habitualmente esto significaba que Alemania necesitaba un ejército gigantesco en caso de que debiera hacer frente a Rusia y Francia juntas. Y la OTAN lo hizo innecesario. Propició la transparencia en asuntos militares en toda Europa y, asimismo, produjo una cooperación militar en lugar de la competencia y ello, junto con la creación de la Unión Europea, hubiera sido posible sin los EE.UU. Ante todo, por esos setenta años de paz tenemos que dar las gracias a Estados Unidos. Ahora bien, creo que esta era está llegando a su fin no porque EE.UU. se marche sino debido a que la atención se está desplazando a Asia. Felizmente, como dirían algunos, la tentación de invadir el Medio Oriente es menor que antes y nosotros, los europeos, tenemos muchos problemas en un entorno donde Ucrania ocupa el lugar destacado de la lista. Aunque si miramos al norte de África, a la zona del Sahel y lo que se encuentra más allá ella, en países como Nigeria, tenemos un gran número de problemas, la mayoría de ellos demasiado pequeños para Estados Unidos. Tuvimos suerte con la Unión Soviética ya que fue un dilema global y EE.UU. lo hizo suyo. Los problemas que enfrenta Europa son regionales antes que globales y Estados Unidos, estoy seguro, ayudará pero Europa tendrá que hacer más.

Michael Ignatieff: Para retomar algo que decía Avishai sobre la enorme explosión de guerras intraestatales, la decadencia de la guerra entre Estados y el incremento al interior de ellos, se trata del fenómeno de la formación del Estado post-imperial que no ha concluido. En cierto sentido, el conflicto árabe-israelí podría considerarse como la formación de un Estado post-imperial. En 1945 contábamos con cuarenta y cinco miembros en las Naciones Unidas y ahora tenemos un noventa y cinco. En mi opinión, esta es una de las grandes victorias de la humanidad ya que significa que millones de personas antes gobernados por otros ahora se gobiernan a sí mismos. En ocasiones no muy bien y en otras sorteando conflictos internos, aunque si uno se pregunta por lo que desea para que el mundo sea más pacífico, deseamos un mundo de Estados responsables, de soberanos responsables y capaces que repartan cantidades indispensables de espacio político a minorías religiosas y étnicas, entre otras minorías sociales. Pienso que es cuestión de júbilo que China no sea el acobardado y humillado poder que fue en 1900 y que ya no esté bajo la insana tiranía comunista de Mao. Veo a mi alrededor un mundo donde las naciones africanas están creciendo firmemente, con países como Ghana cuyas sucesiones democráticas acontecen pacíficamente. Existen muchas fuerzas construyendo la paz y algunas de las fundamentales son la consolidación del orden estatal post-imperial y el surgimiento de un mundo multipolar. Entonces, el desafío de la paz consiste en la forma en que aceptemos y vivamos con este pluralismo. Quiero decir, que aceptamos el hecho de que no van a permanecer en China o Rusia regímenes autoritarios estables y consolidadas que no hagan suyos algunos de los universales. Ellos son los responsables de hacer o no la guerra a otros Estados y de perpetrar o no el genocidio de su propio pueblo. Mis criterios para la responsabilidad son mínimos: no matar a otra gente ni matarse entre sí. Entonces, la interrogante consiste en cómo alcanzar un orden mundial en el que existan regímenes autoritarios que no constituyen una amenaza para sus vecinos. Eso es precisamente lo que se está poniendo a prueba en este momento. Si podemos arribar a ello será algo altamente benéfico. El mundo en que hemos vivido en los últimos setenta años es mejor que el heredado de las ruinas de 1945.

RR: Freud estaría de su lado, nada menos. En cierta ocasión Einstein le preguntó a aquél: “¿Por qué la guerra? Usted es un genio psicológico, explíquemelo”. Al respecto, Freud escribió a la letra: “Podemos descansar con la seguridad de que todo lo que hagamos para el desarrollo cultural está trabajando también en contra de la guerra”. Esta es casi una perspectiva políticamente incorrecta pero se relaciona con los argumentos de usted, Lila, con su idealismo de que sólo mediante los libros, con la literatura, podemos hacer una diferencia. ¿Por qué piensa tal cosa?

Lila Azam Zangan: Recuerdo haber leído uno de mis libros favoritos, Memorias de Adriano, de Yourcenar. Ella habla sobre el emperador Adriano, a quien idealiza un poco: cuando alguien no estaba de acuerdo con él, como al parecer uno de sus secretarios hizo, le lanzaba a la cabeza una de sus tablillas de piedra para matarlo. También era un poco tirano. Nadie es perfecto, era un emperador; pero realmente lo intentó. Y llegó a un final difícil en Israel, con la revuelta de Bar Kojba en Palestina. Así que alguien que realmente trató de ser un pacificador, al final y en cierto modo, falló. Tal vez estamos destinados al fracaso, ¿pero qué importa? La razón por la que me encanta Yourcenar es que en algún punto dice que, en efecto, hemos tenido tantos conflictos, muchas guerras y…, por supuesto, nuestras vidas y espacios privados están infestados de guerras como la enfermedad, el amor no correspondido, la vejez, la muerte. Sin embargo, señala que gracias a la cultura, gracias a esas victorias e incluso gracias al amor, tenemos momentos de inmortalidad. Es por esto que creo en la cultura.

Lila Azam Zangan

Robert Cooper: Eso es muy bonito. Pero debo admitir que si tuviéramos que decir en lo que creemos, yo creo en la política. Porque no me gusta mucho este tiempo en el que parece que vivimos en una gran mediocridad. Aunque quizá siempre parezca así. Sin embargo, si estamos hablando sobre la guerra y la paz es necesario resolver dichos problemas con la gente. Es necesario llegar a compromisos, hablar con la gente y entenderla; es necesario el entendimiento cultural así como la empatía. Necesitamos todas esas cosas aunque, al final, también se necesita la persistencia en la simple búsqueda de compromisos. Tengo una cita… que no es de Blake ni de Tolstoi… En realidad es de otro ruso, quien escribió: “Estamos jalando de ambos extremos de la cuerda. Y enmedio de dicha cuerda se encuentra un nudo llamado guerra. Cuanto más nos retiramos, más apretado se vuelve ese nudo. En algún momento ese nudo puede llegar a ser tan fuerte que incluso quienes lo han atado no puedan desatarlo”. Si usted quiere saber el nombre de este ruso, se trata de Nikita Jruschov. Le está escribiendo una carta al presidente Kennedy en el contexto de la crisis de los misiles cubanos. Para mí esta es una imagen poderosa de lo que en realidad hay que hacer para conseguir la paz. Necesitas dejar de tirar de la cuerda para, así, dejar abierta la posibilidad de desatar el nudo. Y uno consigue la paz cuando se empieza a hablar.

Horia Roman Patapievici: Muy cierto, pero me gustaría añadir otra dimensión. Se trata de una historia sobre Mahoma emprendiendo una batalla menor. Ya de vuelta, le confiesa a uno de sus amigos: “Bueno, esta fue una guerra insignificante, ahora vamos por la gran guerra”. Una guerra que no es otra que la interna. Esta dimensión que quiero añadir no banaliza lo que estamos discutiendo aquí sobre la vida y la muerte, la guerra y la paz, porque cada uno de nosotros posee una dimensión interior en la que ahora mismo se está librando este tipo de batalla interna. Tratamos de lograr la paz, un ideal de todas las filosofías ancestrales. Querían encontrar el equilibrio de la mente o del alma. Deseaban alcanzar la ataraxia, el ser inapasionado. ¿Y por qué esto fue tan importante? Porque el alma, la dimensión interior del hombre, era importante y por la idea de que la realidad interna no constituye la paz sino la guerra. El sabio debe conseguir lo opuesto de lo natural que es la guerra. Lo contrario de la guerra es la pacificación de la mente o del alma. Desde luego, existe una conexión entre lo que la gente hace y sus pensamientos, por lo que creemos que tener buenos pensamientos conduce a una vida benéfica y sin violencia. Si estuviéramos en la antigua Roma o en la Atenas de la antigua Grecia, creo que habríamos comenzado por esta guerra interior.

Avishai Margalit: Cuando oímos decir a la gente “soy un realista” uno suele encontrarse con una tuerca floja. Luego, la gente habla del ser interior y vemos otro tipo de tuerca. El problema no es entre realistas y no realistas. La cuestión es cómo abordar seriamente el dilema de la edificación de la paz en lugares donde hay una guerra. Ahora bien, una gran parte de la tensión se halla en torno de los acuerdos de paz. Aunque el principal problema no son los acuerdos de paz sino su puesta en operación. ¿Quién va a financiar la paz? ¿Quién se ocupará de la seguridad de las personas tras la guerra, cuando las fuerzas armadas se conviertan en facciones violentas? La principal preocupación para los europeos es que habrá millones de personas desplazadas, en calidad de refugiados de esas guerras civiles. Se trata de problemas muy serios que deben atenderse antes de dirigirnos hacia nuestra interioridad.

Michael Ignatieff: Hay un fatalismo fatigado en la idea de que el mundo se va al infierno, lo que constituye un obstáculo para la acción política práctica, además de una suerte de tendencia global de la cual debemos deshacernos. El mundo es complicado y no necesariamente mejor pero ha cambiado enormemente desde 1945. Otro problema es la parcialidad. Se ha dicho aquí que la parcialidad tribal es inevitable. Esto nos conduce a la virtud de los valores universales; a los derechos humanos, por ejemplo. Creo que lo que se puede decir a favor de los valores universales es que constituyen una constante disciplina normativa de la parcialidad tribal. Tal es su propósito. Nunca nos situamos por arriba del hecho de que uno se preocupa por sus ciudadanos, su familia y sus seres más queridos. Pero los valores universales están ahí para decir, espere un momento, usted lleva anteojeras. Y en la medida en que los valores universales tienen una función, creo que se trata de una función política.

Imágenes de © Jelmer de Haas

Gracias al Nexus Intitute por el permiso para publicar esta entrevista

Peace cannot be Imposed it must be Chosen

As water boils one drop boils it bumps against another drop, They bump against two more drops and so on,Soon the whole pot is boiling

You say I am only one drop in the ocean but with Many, Many drops you soon become the ocean.

See our new book “Peace” and how to find it by Christopher Papadopoulos.