Reasons For Poetry

Michelle Gil-Montero

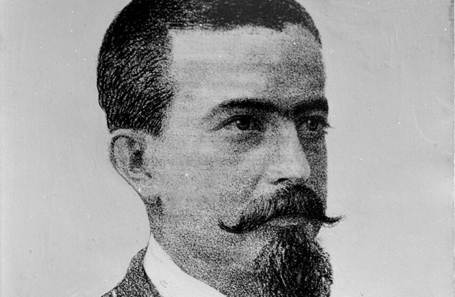

Eduardo Chirinos,

Eduardo Chirinos,

Reasons for Writing Poetry,

Salt Publishing, London, 2011.

Translator: G. J. Racz

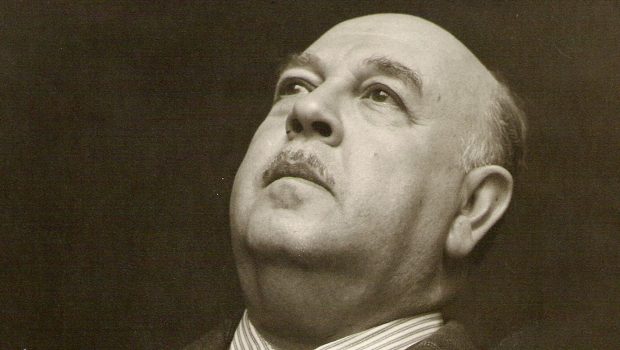

Reasons for Writing Poetry–would such a list be possible to write? In his essay “Reasons for Poetry,” William Meredith speculates that “the reason for a new poem is… a new reason.” By this definition, the list might look like a table of contents or, even better, a book of poems.

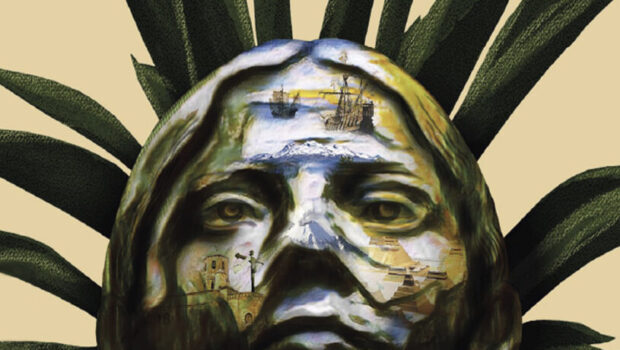

The title suits this substantial first collection in English by Peruvian poet Eduardo Chirinos. Spanning fourteen books–a number that splits neatly into the seven volumes of what critics consider his early work and seven mature volumes–the selection makes it possible, if not irresistible, for the reader to map recurring trends and even track an evolving poetics.

The book opens with poems from The Notebooks of Horacio Morell, written by a 17-year-old Chirinos as the posthumously discovered work of an invented author. Early Chirinos is a poet of masks–literally, in Latin, persona: something “to sound through.” In his monologues and dream narratives, masks are a sounding device, a vehicle for vocal play. The speakers range from Tiresias to Captain Hook, and the tonal dexterity of Racz’s translation expertly conveys this extraordinary range.

For a poet of intense self-awareness, the mask is also a fig leaf. The poems play with concealment even as they mourn the loss of self it entails: “the saddest thing in the world is having no name/to scribble on the back seat of the bus you’re travelling on” (5).

Many poems read as ars poetica. “Like the Ice of a Dark Passion (Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream),” in which the Babylonian king recites his dream to Daniel, suggests a poet in an attitude of vulnerability before the reader. It centers on Nebuchadnezzar’s fear and shame (which peak with desire for his naked mother) and ends on the open question of the poem’s power to mean: “might you perchance reveal the mystery that torments my soul and troubles my senses” (20).

The late poems, marked by a new attention to language, explore similar questions. “Scrawling Crows,” one of several standout prose poems, meditates on the limitations of language; the crows are “winged holes that words fail to reach.” The poem culminates in what seems a characteristic tension for Chirinos: they are both real crows “devouring the carcasses of squirrels and deer” and also mere, inept text (“In the Chinese tradition, scrawling crows means writing badly”) (85).

For its stylistic and thematic range, this book echoes a single, burning question–why do I write? In the title poem, the speaker is a young voyeur, as in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream. Here, however, the dynamics of watching and being watched are more complex. The scene opens on a backward gaze (“That’s when I saw my parents”), meets the gazes of his parents (his mother watching the children from a window, his father reading), and ends when his father sees him peering through a keyhole at his mother bathing. He admits to being moved as much by the beauty of his mother as by the “swift, unmistakable thud of [his] father’s hand” (89). If the book offers a main reason, it is this portrait of the poet, moved as much by the image of beauty as by the shamed feeling that he “lost it forever.”

Posted: May 9, 2012 at 5:17 pm