Self-Constructing

Autoconstrucción

Rose Mary Salum

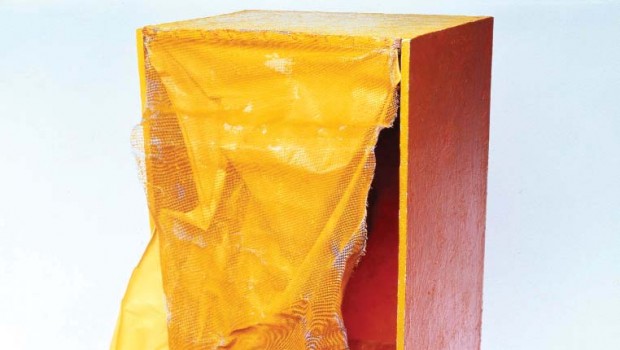

Abraham Cruzvillegas (b. 1968) is one of the most important conceptual artists of his generation. Over the past 10 years, the artist has developed a riveting body of work that investigates what he calls autoconstrucción, or “self-construction.” Featuring 30 to 35 individual sculptures and installations, along with his recent experiments in video, film, and performance, Abraham Cruzvillegas’ exhibition is the first major presentation to shed light on the artist’s unique vision and multifaceted practice.

* * *

Rose Mary Salum: What made you become a visual artist, when your background is in philosophy?

Abraham Cruzvillegas: My background is art and education, not specifically philosophy. The year I started college, in 1985, I held my first art exhibition. I always wanted to be an artist. Yes, I also studied

philosophy, history, literature, journalism, but again: my goal was to be an artist.

RMS: You are not the only artist who uses discarded objects to build art and yet, your art is so different from the rest.

AC: The difference is that I never use garbage. I don’t see the materials I use as garbage, to me, they are objects other people think are dead. But for me, energy and matter never die… that’s all.

RMS: Sometimes, when I see your pieces, my first impression takes me to other cultures, to economic and political realms. Is that something you plan ahead?

AC: Yes. I think of some of my works as internal dialogues about economic clash and unfair distribution of wealth. What is trash for some, is someone else’s gold.

RMS: By “self-constructing,” you are also revealing or unveiling, I would not say the true nature of the objects, but their aesthetic nature, a certain truth that remained unveiled not only to you but to the spectator. You are also unveiling an array of their pragmatic uses. To me, this is the primary motor (in the Aristotelian sense) that moves you to do your work. Are you always in control of the results? Can you share your creative process?

AC: When I select a material to become part of an artwork, I don’t think about the artwork, but rather a possible usage. So, sometimes I collect things for long periods, just accumulating objects that I think are useful, but many times I don’t know what for. I also like to keep the very nature of the materials as I find them, not transforming them at all, or in a very subtle manner, so they can speak for themselves and to allow them to sustain their own dialogues properly, without my voyeuristic intervention. Just on that level: bearing witness.

RMS: For you, transformation occurs in the minds of the viewer, not in your work. Can you elaborate on this?

AC: Art is not really in the objects, but in people’s minds. I believe that things are alive and that they have an influence on us, so we are just forming part of an inner relationship, I think. This triggers interpretations in our understanding. But many times, we don’t want to do that, so we expect the artist to give us clear, finished messages. For me, this is boring. It makes me think that selfish artists produce unique meanings, boring works and lazy audiences.

RMS: By juxtaposing the organic and the manufactured, the handmade and the mass-produced, you remind us of Duchamp, but also you remind me of the very Mexican way of patching things up to make them work. What worldview is rooted in your way of doing things? You are Gabriel Orozco’s pupil. Can you share the influences he has had in your art?

AC: I have many influences, from artisans to filmmakers, poets and musicians. My work is influenced mostly by ordinary people who transform their realities with ingenuity and resourcefulness; this is something human, not Mexican or from the art world. My worldview is more like an ideology: I invent solutions according to specific needs. Each work demands a specific way of making it. There’s no homogeneous way of thinking in my work or in my mind, I’m very contradictory. I love instability, both conceptual and physical. Gabriel Orozco is a great artist and a great friend.

RMS: You’ve said, “After transforming something, I want it to be ready to be transformed again, by interpretation, by physical decay, by its own weight, by time. It happens anyway. That’s why I don’t like the idea of production, because it means arriving at the end, not a beginning.” However, your art will always remain permanent through the very images taken at your exhibitions. How do you deal with this contradiction?

AC: Interpretation happens with images as well. But contradiction happens in interpretation also. Archives and catalogues are subject to both of these.

RMS: Helio Oiticica has a piece titled Vermelho cortando o branco. The piece Autoconstrucción reminds me of that. How did you arrive at this aesthetic conclusion?

AC: The work you refer to is part of a series called Blind Self Portrait. I collect papers from my everyday life and I paint them on the back, which is the side you can see. The visual arrangement of the works is highly random, so they can appear as grids, or chaotic patterns, lines or messy ovals. I like that you thought about Hélio’s beautiful work, but I’m far from being as smart as he was.

RMS: When I think of your name, La curva and La polar immediately come to mind. Would you share how you conceived of these pieces?

AC: These works are more related to playfulness, but activating it, rather than talking about it. I just play.

RMS: Your art is often considered part of a new movement in Latin American art (which has been compared to the YBA boom in Britain in the 1980s). In your opinion, why is it that you are so well known in Mexico and Europe, whereas people hardly know your work here in the US?

AC: Since I was 21 years old, I’ve been told I’m part of a movement in Latin America, so now it’s been 24 years since it was said the first time. I think of myself as an intergalactic indigenous person, not as Latin American, Mexican or Chilango. I’m all of these things at the same time, but my language –when I make art– is more a Tower of Babel where everything fits in. In fact, I feel as close to some Scottish, Korean, Italian or French artists, as I do to some Peruvian, Argentinian, Mexican or Colombian artists. I’m also very well-known in the US: I have lots of friends around…

RMS: This exhibition promises to illustrate your contributions and the motivations and influences that have informed your thought, as well as your commitment to social and political realities that shape everyday lives. In your opinion, have you accomplished at least half of what you wanted to accomplish when you started out as an artist?

AC: In my perception, in the context you are talking about, I haven’t accomplished anything yet. But the exhibition at the Walker is the best beginning I ever could have dreamed of; I’m very proud and happy about it!

Rose Mary Salum is the founder and director of Literal, Latin American Voices. She´s the author of Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) among other titles.

Rose Mary Salum is the founder and director of Literal, Latin American Voices. She´s the author of Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) among other titles.

Abraham Cruzvillegas (n.1968) es uno de los artistas conceptuales más importantes entre sus contemporáneos. Durante los últimos 10 años ha trabajado en torno de lo que llama “auto-construcción”. En esta puesta en escena Abraham Cruzvillegas muestra entre 30 y 35 esculturas individuales e instalaciones, así como vídeos, filmes y performances. Se trata de la primera muestra que arroja luz sobre la visión única de este artista y su práctica multifacética.

* * *

Rose Mary Salum: ¿Qué te motivó a ser un artista visual cuando tus estudios fueron en filosofía?

Abraham Cruzvillegas: Mis antecedentes también son en arte y educación y no necesariamente en filosofía. El año que entré a la universidad, realicé mi primera exhibición en 1985. Siempre quise ser un artista y pese a que estudié filosofía, historia, literatura, periodismo, mi intención era la de ser un artista visual.

RMS: No eres el único que usa objetos de la basura para crear arte y sin emabargo, tu trabajo es muy distinto al de otros.

AC: La diferencia es que nunca uso basura. No veo los materiales empleados como basura. Son objetos que la gente considera muertos pero para mí la energía y la materia nunca mueren. Eso es todo.

RMS: Cuando veo algunas de tus piezas, me llevan a pensar en otras culturas, en la política y la economía. ¿Es planeado o fortuito?

AC: Sí. Veo algunas de mis piezas como diálogos internos que me llevan a pensar en la disparidad y la injusta repartición de la riqueza. Lo que es basura para algunos, es oro para otros.

RMS: En Autoconstruyendo o Self-Constructing Yourself, estás mostrando algo. No diría que la verdadera naturaleza de los objetos, pero sí su naturaleza estética; una cierta verdad que no era evidente para ti ni para el espectador. También señalas una serie de usos prácticos. Para mí éste es el primer motor (en el sentido aristotélico) que te lleva a crear. ¿Podrías comentar tu proceso de trabajo?

AC: Cuando escojo un material para que sea parte de una pieza no pienso en la obra de arte pero sí en su posible uso. En ocasiones guardo objetos durante mucho tiempo sólo con el afán de acumular cosas que pueden tener un uso, aunque a menudo no sé en qué acabarán. También me gusta preservar la naturaleza de los materiales conforme los voy encontrando, sin transformarlos; o quizá de forma muy sutil, para que puedan hablar ellos mismos. De este modo les permito realizar sus propios diálogos, sin intervención voyerística pero sí de testigo.

RMS: Para ti la transformación ocurre en la mente del espectador, no en el trabajo. ¿Podrías abundar al respecto?

AC: El arte no está en los objetos sino en la mente de las personas. Yo creo que que las cosas están vivas y nos influyen. Sólo estamos siendo parte de una relación interior que detona interpretaciones en nuestro entendimiento. Pero en muchas ocasiones, no lo queremos hacer y quedamos a la espera de que el artista nos de mensajes claros y terminados. Para mí resulta aburrido y me hace pensar que los artistas ególatras producen significados únicos, trabajos aburridos y espectadores flojos.

RMS: Cuando yuxtapones lo orgánico a lo manufacturado, lo hecho a mano y la producción en masa, nos recuerdas a Duchamp, pero también me haces pensar en esa costumbre muy mexicana de parchar y transformar objetos para darles una nueva función. Tú estudiaste con Gabriel Orozco, ¿qué influencia ha tenido en tu trabajo?

AC: Tengo marcas de artesanos, cineastas, poetas y músicos. La huella que mi trabajo ha recibido proviene de gente común y corriente que busca, ingenua o inventivamente, transformar su realidad. Esto es humano, no mexicano o exclusivo del mundo del arte. Mi comovisión es más como una ideología. Invento soluciones de acuerdo a necesidades especificas. Cada trabajo demanda una forma de manufactura concreta, no hay un pensamiento homogéneo en mi trabajo o en mi mente. Soy muy contradictorio. Me gusta la inestabilidad: tanto la conceptual como la física. Gabriel Orozco es un gran artista y amigo.

RMS: Has dicho que “después de transformar un objeto, quiero que esté listo para volver a ser transformado: ya sea para interpretarlo, por decadencia física, por su propio peso, por el tiempo. Por eso no me gusta la idea de producción, porque intrínsecamente propone un final, no un principio.” Sin embargo, tu trabajo incide y sobrevive gracias a las imágenes que fueron tomadas durante tus exhibiciones. ¿Cómo enfrentas esta contradicción?

AC: La interpretación también se da con las imágenes. Pero la contradicción también sucede en la interpretación. Los archivos y catálogos se someten a estas dos.

RMS: Helio Oiticica tiene una pieza titulada Vermelho cortando o branco. Tu Autoconstrucción me recuerda aquella otra. ¿Cómo llegaste a esta conclusión estética?

AC: El trabajo al que te refieres es parte de una serie llamada Autoretrato ciego. Colecciono papeles de mi vida diaria y los pinto en la parte posterior, la parte que se puede ver. La composición visual de los trabajos es fortuita con el objeto de que parezcan cuadriculas o patrones caóticos, líneas u óvalos caóticos. Me gusta tu opinión sobre el trabajo de Helio, pero estoy muy lejos de ser tan inteligente como él.

RMS: Cuando pienso tu trabajo de inmediato viene a mi mente La curva y La polar ¿Cómo concebiste estas piezas?

AC: Son un ejercicio que busca activar una naturaleza juguetona. Más que hablar de ella, juego.

RMS: A menudo tu trabajo es considerado parte del nuevo movimiento artístico de Latinoamérica (el cual ha sido comparado al boom YBA en la Inglaterra de los años ochentas). ¿A qué atribuyes el reconocimiento recibido en México y Europa y el hecho de que apenas te conozcan en Estados Unidos?

AC: Desde que tenía 21 años, me han dicho que soy parte de un movimiento latinoamericano y ahora han pasado 24 años después de que se dijo por primera vez. Yo me pienso a mí mismo como un indígena intergaláctico, no como latinoamericano, mexicano o chilango. Soy todo ésto al mismo tiempo, pero mi lenguaje –cuando hago arte– es como una torre de Babel donde todo se acomoda. Incluso me siento tan cerca de algunos artistas escoceses, coreanos, italianos o franceses como de algunos artistas peruanos, argentinos, mexicanos o colombianos. También soy muy conocido en Estados Unidos: estoy rodeado de muchos amigos…

RMS: Esta exhibición promete ilustrar las contribuciones, motivaciones e influencias que han formado tu pensamiento así como tu compromiso con realidades sociales y políticas. ¿Crees que has alcanzado al menos la mitad de proyectos que te propusiste cuando empezaste tu carrera?

AC: En mi percepción, en el contexto del que tú estás hablando, aún no he conseguido nada. Pero la exhibición en el Walker es el mejor comienzo que pude haber soñado. ¡Estoy orgulloso y feliz por eso!

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto 2015) y Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing 2013) entre otros títulos.. Su twitter @rosemarysalum

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto 2015) y Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing 2013) entre otros títulos.. Su twitter @rosemarysalum