Gustavo Díaz: The Art of Questioning

Gustavo Díaz: El arte de interrogar

Rose Mary Salum

We had the opportunity to talk to Gustavo Díaz, one of the most promising artists in that country.

* * *

Rose Mary Salum: It strikes me how fascinated you seem to be with the concept of complexity. I’d like to know if this has to do with mental or artistic complexity, or if it relates to science?

Gustavo Díaz: Complexity is all that exists in the universe. On micro and macro scales, every process is complex, from breathing to walking. We assimilate the most basic, habitual processes as natural to us, but they actually come about as the result of macro or micro complexes. I am quite passionate on this subject at any scale. When you zoom in on your own gaze or concepts and see the small details of things, they possess formal, functional, and operative complexities. The same thing happens when we observe on a macro scale.

I feel this is an important matter. It’s a very timely subject, given that the world is gaining complexity on all levels. The growth of cities and transportation systems, for example, display high entropy, transformation that leads to disorder. All these are ideas that can be considered in the context of physics, but also of sociology, philosophy, anthropology, etc. One can consider complexity from within different disciplines, because it is present in everyday life.

RMS: That’s true. You started out working with glass and acrylic, something that in a way constituted your first formal rupture. And from that point on, you began a trajectory rooted in science.

GD: My approach deals with the questions that science asks. It’s quite interesting to me how science profoundly redefined itself. It came equipped with the classical burden of Euclidian thinking, Newtonian thinking, all that logic, until the turn of the last century. The first two decades of that century were of great inventions, with the appearance of the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. A “hypothetical physics” came into being. A new reality imagined on non-human scales, as both micro and macro universe. From both worlds emerged the theory of relativity (macro universe) and quantum mechanics (micro universe). These two dynamics began to generate a series of ideas that broke significantly with the world of science. The mathematician Gödel, who wrote the theory of incompleteness in 1921, brought new paradigms to the world of logic.

So there are a ton of changes during those decades and they fascinated me as questions. I don’t have scientific training, but I have a sort of approach to this world through systems theory. A new hyper- creative, hypothetical, conjectural, probabilistic science arose, unique in that it included mankind. The previous science had nothing to do with human beings. In current quantum mechanics, on the other hand, the observer has an importance that is undeniable in that he modifies what he sees. There are situations that put the subject back at the center of inquiry, and of the universe, too, obviously.

RMS: Apart from complexity, and the “world of questions,” how do you conceive of interference and rupture?

GD: I declare myself a fervent defender of the world of questions, not so much of that of answers. I am fascinated by the realm in which we question, where there is room for doubt; given that we open pathways toward reflection. Among these questions, for example, one can meditate on the idea of linearity and how it is broken. Classical science understood that many events had a lineal, spatial-temporal logic. At some point, we began to rethink space and time as classic paradigms. One believes that there’s nothing new in linearity: all events take place continuously. Disrupting that linearity has to do with the contemporary world; there is room for novelty, for randomness, for situations that, in this very manner, obey a logic unlike that of classical science. Conceptually, I defend this rupture; it gives us the possibility of new information and creativity. In some of my pieces I work with the concept of noise, which also relates to disruption: interference is something that happens when linearity is fractured. Noise as a sonorous concept interests me because we live in a universe that includes noise. In fact, John Cage, with his 4’33”, created a model for meditating on silence in music.

RMS: So, do you believe that we may be able to decide some of these scientific questions through art?

GD: I understand them to be distinct universes. There may be border regions between these two domains, but art is communication and this is its goal, beyond the scientific. I obviously choose art along with curiosity about scientific questions, but I tend toward communication as a concept. This is a world of connections.

RMS: Your work generates the perception of movement in the spectator, contributing in this way to a physical interpretation of instability. Likewise, some of your pieces coincide with kinetic art. Is this a conscious influence?

GD: In my work, I deal with five or six thematic groups. In one of these, I subtly brush up against the world of optics, but not intentionally. Those pieces that seem to be optical actually examine chaos or catastrophe theory. Because I used lines and there is a visual effect that occurs in the viewer’s perception, they can be associated with the optical world. I’m clearly conscious of that, but it was not my original intent. The masters of the world of optical art and their inventions are pre-digital. I recognize the achievement in that sort of work. On the other hand, I don’t find any merit in practicing optical art in the year 2012. With the digital world at our disposal, to be optical comes close to being intellectually lazy. When my work is associated with the world of optical art, I’m uncomfortable. I even stopped working on some pieces precisely for this reason. I recognize the mastery of those artists, but in today’s world, we need to explore other paths.

RMS: Could you tell us more about these thematic groups your work explores?

GD: It’s all complex, like I said. It would be difficult to explain these aspects of my work.

RMS: Perhaps you could give us a general description?

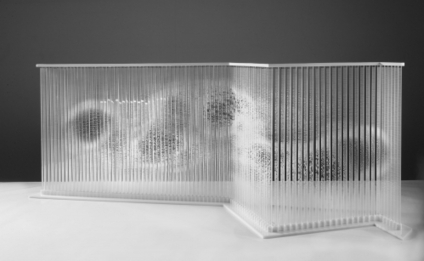

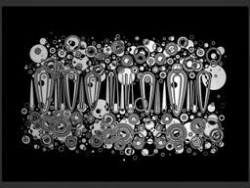

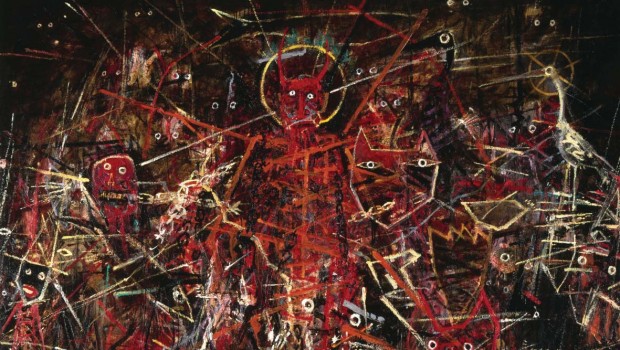

GD: The first group includes great boxes of Plexiglas acrylic with many small boxes within. In this group, I create basreliefs that stretch out to the wall, and recently I’ve worked with others that expand to the floor. This set deals with viral information codes. The second consists of ink on illustration paper, where I explore the idea of webs, networks, links, and hyper-links. The third includes transparent objects where the theme is organized complexity. I work with Ilya Prigogine’s principle – the one that earned him the Nobel in ‘77 – in which he studies the behavior of structural stabilities within complex systems. I revisit this idea because it modifies conceptions of order and disorder in systems and allows us to reconsider, to understand whether some words can still be used in these contexts. For example, the words ‘order,’ ‘structure’, etc. Thus I study structural stability, complexity organized through objects with many sheets, perhaps 20 or 30, of high visual entropy. The fourth group consists of pencil drawings in which I study the Porphyrian tree as a structural concept, and rhizomes. These concepts interest me because on a linguistic level, they’re a counter- point between Chomsky and Deleuze. In these drawings, for example, I display an interest in the concept of rhizomes. These days, we have changed our way of organizing; in the last two decades, the world has become rhizomatic. Social networks have rhizomatic structures and this is why they work so well, but at the same time they have a vocabulary that is consistent with the Porphyrian tree. This combination of rhizomatic and Porphyrian structures fascinates me. Finally, I have some work in ink relating to chaos theory, and a few drawings in the same medium that contain graphical musical scores for sound art.

RMS: The last question has to do with the future of art. You propose an aesthetic based on scientific questions. Do you think this will replace the aesthetic where visual elements were fundamental? As you mentioned, now that we are in a digital age, some artistic trends must be redefined. This happened with the avant-garde, in response to the photograph. How might we rethink art?

GD: We don’t know, but we can speculate. In the Bauhaus tradition it was said that there is a knowledge that travels from the head to the hand and another from the hand to the head, and both complement a form of knowledge. I believe that there is a possible pathway from algorithm to subject, subject to algorithm. Both pathways interest me. There’s an MIT professor who has developed a concept of tangible bits. I’m fascinated by his theory about a world of bits, but tangible ones. I’m interested in moving from the monitor to the realm of the human being. If you use the logic of the monitor, it’s like incorporating contemporary reasoning into the digital world. I’m interested in the actual existence of the subject. I’m interested in work that comes out of the monitor. I’m not inclined to think of the digital world as a generator of artistic work, as a thought structure. But I am interested in a man with a sheet of paper and a pencil. There is a romantic gesture in this, a classical gesture, if you will. Perhaps this romantic gesture is manifest in my work. All of the pieces I create are produced by me. I am the one who polishes the objects. There is a making that I am interested in, aside from the concept itself. That making makes me happy on a daily basis. It’s a position that is not so contemporary, because we live in an era in which artists, for several decades now, have hardly produced their own work. I seek to position myself within the group that still creates its own work. The pathway to the future is uncertain. What is interesting about chaos theory is that any small variation in a system’s initial conditions gives rise to an uncertain complexity that can lead to unexpected places. This is fascinating. Our future is open and multiple.

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de Donde el río se toca (Sudaquia, 2022), Tres semillas de granada, ensayos desde el inframundo (Vaso Roto, 2020), Una de ellas (dislocados, 2020). El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto, 2015), Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) (Versión Kindle) y Entre los espacios (Tierra Firme, 2003), entre otros títulos. Sus obras se han traducido al italiano, búlgaro y portugués. Su Twitter es @rosemarysalum

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de Donde el río se toca (Sudaquia, 2022), Tres semillas de granada, ensayos desde el inframundo (Vaso Roto, 2020), Una de ellas (dislocados, 2020). El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto, 2015), Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) (Versión Kindle) y Entre los espacios (Tierra Firme, 2003), entre otros títulos. Sus obras se han traducido al italiano, búlgaro y portugués. Su Twitter es @rosemarysalum

Tuvimos la oportunidad de conversar con Gustavo Díaz, uno de los artistas argentinos más prometedores de su país.

* * *

Rose Mary Salum: Me llama la atención la fascinación que muestras por el concepto de complejidad. Quisiera saber si te refieres a la complejidad mental y artística o si tiene que ver con la ciencia.

Gustavo Diaz: No existe más que complejidad en el universo. En la micro y macro escala, todo es complejidad, desde el proceso de respirar hasta el de caminar. Las cosas más elementales que tenemos por hábito aprendido, las incorporamos como algo natural aunque en realidad son el resultado de macro o micro complejos. El tema me apasiona en todas sus escalas. Cuando uno hace un zoom de sus conceptos o mirada y ve los pequeños detalles de las cosas, éstas poseen complejidades formales, funcionales y operativas. Lo mismo sucede cuando observamos la macro escala.

Siento que es un gran tema, muy actual dado que el mundo aumenta de complejidad en todos sus aspectos. El crecimiento de las ciudades y los sistemas de tránsito, por ejemplo, son de alta entropía, de transformación orientada al desorden. Tales temas se pueden pensar desde el mundo de la física pero también de la sociología, filosofía, antropología, etc. La complejidad está presente en la vida cotidiana.

RMS: Es cierto. Comenzaste trabajando sobre vidrio y acrílico, algo que, de alguna manera, constituyó tu primera ruptura formal. A partir de ese momento, comenzaste una trayectoria cuyas raíces, incluso, se encuentran en la ciencia.

GD: Mis aproximaciones giran en torno a las preguntas que se hace la ciencia. Me parece muy interesante cómo la ciencia se repensó profundamente. Venía con una carga de pensamiento euclidiano y newtoniano clásicos, con toda su lógica, hasta comienzos del siglo pasado. Las dos primeras décadas de ese siglo, con la aparición de la teoría de la relatividad y la mecánica cuántica, fueron de grandes invenciones. Emergió una “física hipotética”. Una nueva realidad a escalas no humanas, tanto en el micro como en el macro universo. De ambos surgió la teoría de la relatividad (macro) y la mecánica cuántica (micro). Las dos dinámicas generaron rupturas en el mundo de la ciencia. El matemático Göedel, quien en 1921 formuló la teoría de la incompletitud, sumó nuevos paradigmas al mundo de la lógica. Durante esas décadas, repito, sucedió un gran número de cambios que a mí me apasionan como preguntas. No cuento con una formación científica, pero realizo una especie de aproximación a este mundo a través de la teoría de sistemas.

Esta nueva ciencia hiper creativa, hipotética, conjetural y probabilística, tiene la particularidad de incluir al hombre. La ciencia anterior era ajena al ser; en la actual mecánica cuántica, por el contrario, el observador tiene una importancia indiscutible en la medida que modifica lo que observa. Hay situaciones en que el sujeto vuelve a ser el centro de las preguntas y, también, del universo.

RMS: Además de la complejidad y del “mundo de las preguntas”, ¿qué concepto tienes sobre la interferencia y la ruptura?

GD: Me declaro un ferviente defensor del mundo de las preguntas, no tanto de las respuestas. Me fascina el orbe donde se interroga y se da cabida a la duda ya que así abrimos un camino a la reflexión. Entre las preguntas, por ejemplo, uno puede pensar en el tema de la linealidad y su ruptura. La ciencia clásica entendía que muchos de los sucesos tenían una lógica lineal espacio-temporal. Pero en algún momento empezamos a repensar el espacio y el tiempo en tanto paradigmas clásicos. Uno cree que en la linealidad no hay nada nuevo: todos los eventos se suceden continuamente. La ruptura de esta linealidad tiene que ver con el mundo contemporáneo, donde hay espacio para lo nuevo y ocasional así como para situaciones que, justamente, obedecen a una lógica distinta de la ciencia clásica. Conceptualmente, soy un defensor de esta ruptura; ella nos da la posibilidad de información nueva y de creatividad. En algunas de mis obras trabajo sobre el concepto de ruido, que también tiene que ver con el de ruptura: la interferencia sucede cuando la linealidad se fragmenta. El ruido como concepto sonoro me interesa porque vivimos en un universo que incluye el ruido. De hecho, John Cage, con su obra 433, generó un paradigma y reflexión sobre el silencio en la música.

RMS: ¿Crees entonces que se puedan abordar algunas de esas preguntas científicas a través del arte?

GD: Entiendo que son universos distintos. Puede haber zonas fronterizas entre los dos pero el arte es comunicación; ese es su objetivo, más allá de lo científico. Obviamente, prefiero el arte con curiosidad sobre ciertas preguntas científicas, aunque me inclino por la comunicación como concepto. Éste es un mundo de conexiones.

RMS: Tu obra genera en el espectador percepciones de movimiento, de cierta lectura física de la inestabilidad. Asimismo, algunos de tus

trabajos muestran coincidencias con el arte kinético. ¿Es una influencia consciente?

GD: En mi obra trabajo sobre cinco o seis grupos temáticos. En uno de ellos rozo sutilmente el mundo del arte óptico pero sin intención de serlo. Esas obras que parecen ser ópticas, en realidad estudian la teoría del caos y de la catástrofe. Como uso la línea y hay un efecto visual que sucede en la percepción del que observa, puedo ser asociado al mundo óptico. Soy claramente consciente de ello pero esa relación es ajena a mi intención original. Los maestros del mundo óptico en el arte y sus invenciones son predigitales. Reconozco un logro en ello. En cambio, no admito ningún mérito tratándose de un artista óptico en el 2012. Tras el advenimiento digital, ser un artista óptico es casi una pereza intelectual. Cuando a mi obra se le relaciona con el mundo óptico me siento mal. Incluso, abandoné algunos de mis trabajos justo por eso. Reconozco la maestría de ese tipo de artistas pero, hoy por hoy, es otro el camino que debemos experimentar.

RMS: ¿Podrías hablar de esos grupos temáticos que abordas?

GD: Todo es complejo, ya lo dije, y explicar tales aspectos sería difícil.

RMS: Quizá puedas describirlos grosso modo…

GD: El primer grupo incluye grandes cajas de acrílico plexiglass con muchas cajas pequeñas dentro. En este grupo trabajo con relieves que se expanden hasta la pared y, recientemente, con otros que descienden hasta el piso. El conjunto hace referencia a códigos virales informáticos. El segundo consiste en tintas sobre papel ilustración para abordar el concepto de tramas, redes, vínculos e hipervinculos. El tercero incluye objetos transparentes donde el tema es la complejidad organizada. Trabajo con el principio de Prigogine –con el que Ilya Prigogine obtuvo el premio Nobel en 1977–, el cual estudia el comportamiento de estabilidades estructurales en sistemas complejos. Lo retomo porque modifica el concepto de orden y desorden de los sistemas y nos permite pensar de nuevo, entender si algunas palabras pueden seguir siendo usadas en tales contextos. Por ejemplo, las palabras orden, estructura, etc. Analizo así la estabilidad estructural, la complejidad organizada mediante objetos con múltiples placas, unas 20 o 30, con una alta entropía visual. El cuarto grupo consiste en dibujos a lápiz dedicados al árbol de Porfirio como concepto estructural y de rizoma. Me intereso en estas ideas porque, en su nivel lingüístico, son un contrapunto entre Chomsky y Deleuze. En esos dibujos, por ejemplo, expongo mi interés por el concepto de rizoma. Vivimos en tiempos donde hemos cambia- do nuestras formas de organización y en las últimas dos décadas el mundo se ha vuelto rizomático. Las redes sociales tienen estructuras de este tipo, rizomaticas, y por eso funcionan bien. Su vocabulario, a la vez, obedece al árbol de Porfirio. Esta combinación de estructuras rizomáticas y de Porfirio me resulta apasionante. Por último, cuento con trabajos de tinta a propósito de la teoría del caos y algunos dibujos con la misma técnica que contienen partituras gráficas de obras sonoras.

RMS: La última pregunta tiene que ver con el futuro del arte. La tuya es una estética apoyada en las interrogantes de la ciencia. ¿Crees que esa estética va a reemplazar a aquella donde lo primordial es la parte visual? Como mencionabas, en plena era digital hay que replantear algunos movimientos artísticos. Eso sucedió con la vanguardia frente al desafío de la fotografía. ¿Cómo repensar el arte?

GD: No lo sabemos, pero podemos especular. En la Bauhaus decían que hay un conocimiento que va de la cabeza a la mano y otro de la mano a la cabeza y que ambos complementaban una forma del conocimiento. Yo creo que existe un camino posible entre el algoritmo sujeto, sujeto algoritmo. Ambos caminos me interesan. Un profesor del MIT ha ideado el concepto de bitangibles. Me apasiona su teoría sobre un mundo de bits pero tangibles. Me interesa ir del monitor al mundo del ser. Si usas la lógica del monitor es como incorporar el razonamiento contemporáneo al mundo digital. Me interesa la existencia propia del sujeto. Me interesa la obra que sale del monitor. No me inclino por el mundo digital como generador de obras, como estructura del pensamiento, pero sí me interesa el hombre con una hoja y un lápiz. Allí hay un gesto romántico –o si se quiere, clásico. Mi trabajo tiene ese gesto tal vez romántico. Todas las piezas que hago están producidas por mí. Los objetos están pulidos por mí. Hay un hacer que me interesa, además del concepto. Ese hacer cotidiano me hace feliz. Se trata de una postura que no es tan contemporánea porque vivimos en tiempos en que los artistas –desde hace muchas décadas– apenas si producen sus propias obras. Mi deseo es situarme dentro de ese grupo que aún produce sus propias obras. El rumbo futuro es una incógnita. Lo interesante de la teoría del caos es que cualquier pequeña variación en las condiciones iniciales de un sistema desatan una complejidad incierta que lleva a lugares insospechados. Eso es apasionante. Tenemos un futuro abierto y múltiple.

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de Donde el río se toca (Sudaquia, 2022), Tres semillas de granada, ensayos desde el inframundo (Vaso Roto, 2020), Una de ellas (dislocados, 2020). El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto, 2015), Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) (Versión Kindle) y Entre los espacios (Tierra Firme, 2003), entre otros títulos. Sus obras se han traducido al italiano, búlgaro y portugués. Su Twitter es @rosemarysalum

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de Donde el río se toca (Sudaquia, 2022), Tres semillas de granada, ensayos desde el inframundo (Vaso Roto, 2020), Una de ellas (dislocados, 2020). El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto, 2015), Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) (Versión Kindle) y Entre los espacios (Tierra Firme, 2003), entre otros títulos. Sus obras se han traducido al italiano, búlgaro y portugués. Su Twitter es @rosemarysalum