The Chronicler

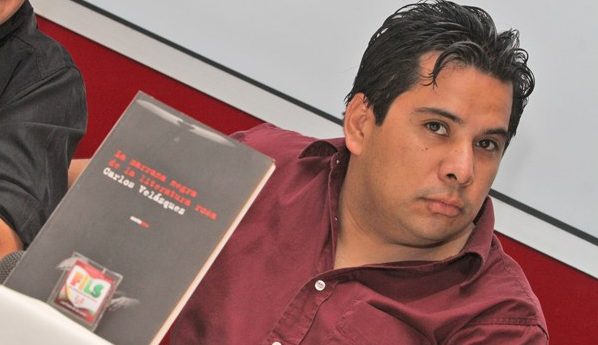

Ilan Stavans

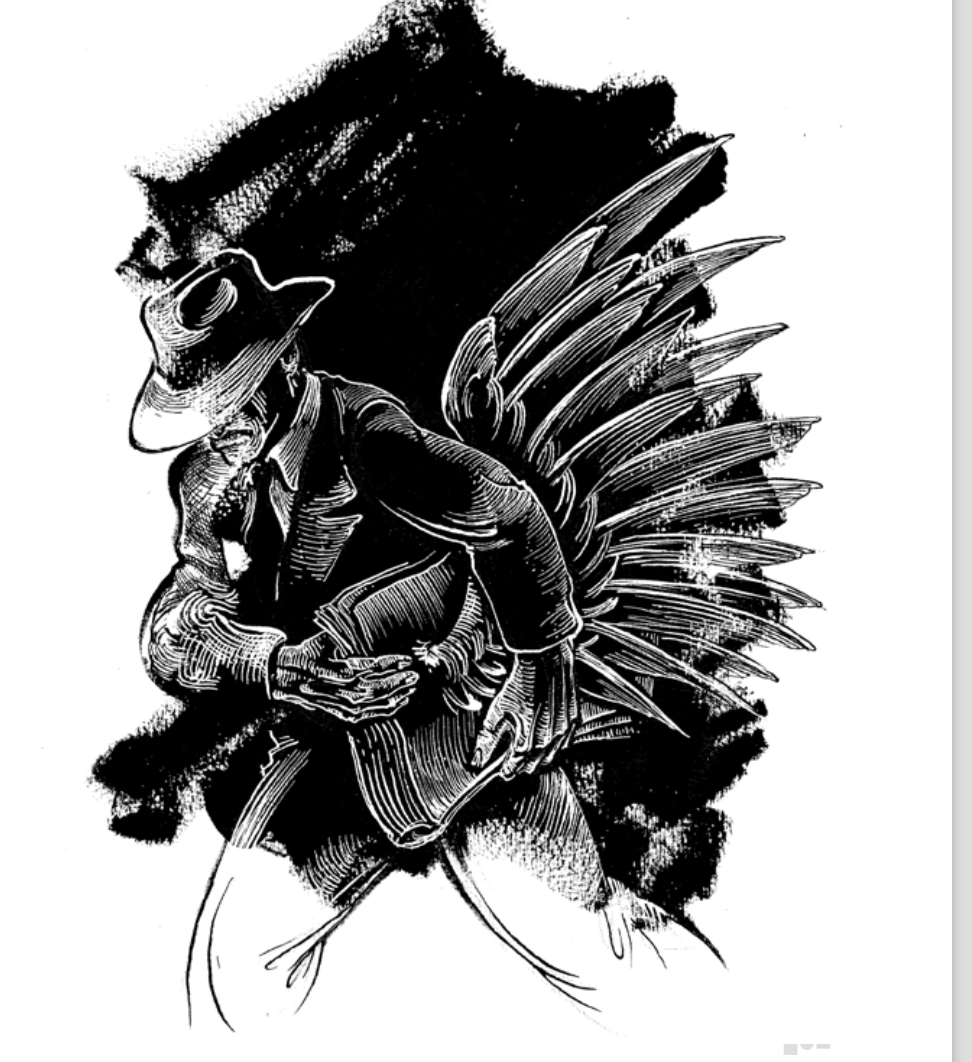

The following constitutes chapter 3 of Ilan Stavans’ new book The Return of Carvajal: A Mystery (PSUP, with etchings by Eko), due out in October, which explored the resurfacing of the long-lost handwritten autobiography of Luis de Carvajal the Younger, also known as El Iluminado, the most prominent Crypto-Jew in colonial Mexico, burned at the stake by the Holy Office of the Inquisition in 1596.

***

In 2016, in the early part of summer, I received an unexpected email. It was from my old friend Esther “Starry” Schor, who teaches English at Princeton and is the author of an award-winning biography of Emma Lazarus and a book on the development of Esperanto as a global language. I hadn’t talked to Starry for some time. She said that a friend who was a Princeton alum and the donor of the Milberg Collection of Jewish American Writers was interested in purchasing an item by Carvajal recently put on sale she wanted to know if I would be ready to advise the collector on the purchase.

She attached a link to the Swann Action Gallery in Manhattan, which described in part the item: “Early transcript of Inquisition victim Luis de Carvajal autographical Memorias with devotional manuscripts.” It also stated: “the present volume clearly dates not long after Carvajal lifetime.” Knowing its historical relevance, I alerted Starry about it possibly being the stolen booklet. I described in some detail the theft that took place more than eighty years ago. I myself had come to experience a tacit resignation about Carvajal’s memoir, thinking it would never show up again. Truth is, while this was a document of uncontested historical value no one really seemed to care. As a Mexican, I have always felt that the country’s disarming chaos contributes to its patrimony being chipped off slowly every year.

A while before, together with artist Steve Sheinkin, I had turned Carvajal into a character in a graphic novel, El Iluminado (2012). I had done this playfully, creating a thriller—with a “nosy” professor as protagonist, whose name is Ilan Stavans—about a rivalry between scholars connected with the loss of a historical manuscript. More so, I wanted to attach Carvajal to the ebullient movement of Crypto-Jewish awakening in the American Southwest in the early twenty-first century. My inspiration was Umberto Eco’s medieval thriller The Name of the Rose (1980), which was, at least in part, inspired by the metafictional world of the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, one of my favorite writers. My graphic novel was enthusiastically received. It brought me numerous letters, Facebook messages, Tweets, and other correspondence from Crypto-Jews in northern Mexico and the American Southwest.

Borges was in my mind when I wrote El Iluminado. The plot takes place in present-day Santa Fe. I myself am one of the protagonists. Considerable elements of the content resulted from a series of trips I made to New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and to northern Mexico in the first decade of this century. It depicts the way I had become infatuated with the tribulations of the Crypto-Jews and wanted to reflect on it in fiction. I studied closely the making on the Cathedral Basílica of St. Francis of Assisi in downtown Santa Fe, especially an inscription—in Hebrew letters—of the Tetragrammaton on the entrance arch. The character of Archbishop Jean-Baptiste Lemy, the protagonist of Willa Cather’s Death Comes to the Archbishop (1927), plays a role. Lemy is the hinge that connects the Cathedral Basílica to a couple of earlier religious buildings on the same, at least one of which was funded in part with Jewish money. Santa Fe, the graphic novel argues, was a refuge for Crypto-Jews eager to keep the appearance of a New Christian life by donating funds to a Catholic Church in order not to attract attention to their hidden practices. Archbishop Lemy was partially aware of this double identity.

It was during my Santa Fe trips that I reread the work of Carvajal. Aware of the missing memoir, I fantasized the passage of a booklet that travels from Mexico City to the American Southwest, ending up in the avid hands of devout Crypto-Jews. My interest pushed me in countless directions. I had read with admiration Cohen’s thoroughly-researched biography. The blueprint of Carvajal’s hardship is set out clearly in it: the biography looks at religious persecution in the New World as a subterfuge for centralized political control.

This was only the tip of the iceberg. Carvajal, I quickly found out, was the inspiration for operas, films, and a variety of fictional accounts, among other artistic manifestations, rotating around him. Arturo Ripstein, a prominent Mexican filmmaker of Jewish heritage whose career started when he was an assistant to Spanish director Luis Buñuel, made El Santo Oficio (1974), which was nominated for a Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. It is a period piece loosely based on the Carvajal family. I read novels written in as far away as Australia about Carvajal. And at the Ransom Humanities Center in Austin, Texas, there is a manuscript by American-born Anita Brenner, one of the most noteworthy commentators on Mexican art in the twentieth century and the author of the seminal Idols behind Altars (1929). Brenner, who studied under Franz Boas and was close with Diego Rivera, with whom she often fought, wrote for The Nation as well as for American Jewish publications. Her focus in the Carvajal manuscript isn’t Carvajal himself but his mother and sister.

Soon after my exchange with Starry, I was having a conversation with Leonard L. Milberg himself. Leonard L. Milberg was the chairman of Milberg Factors, a commercial finance company that was found by his father and has been around since 1937. A tall, insistent, passionate man of 85, he was a graduate of Princeton and the Wharton School. Originally from Flatbush, he is known for his private collections of Irish literature and early American documents. Over the years, Milberg had donated substantial amounts of money to Princeton to expand its Irish studies program. He has funded exhibits on Jewish life in the early American Republic.

In his eyes, this aspect was connected to the growing anti-Semitism in the world today. As he told me during a lunch in the cafeteria of the New York Historical Society, “I hope this effort educates people on the active role Jews played in shaping our society.”

We were there because the veteran institution on Central Park West in New York City’s Upper West Side founded by DeWitt Clinton, the American politician and naturalist who served as a United States Senator, Mayor of New York City and sixth Governor of New York, was preparing an exhibit called “The First Jewish Americans: Freedom and Culture in the New World.” It would be ready soon. The exhibit had started at Princeton and was moving to the New York Historical Society. It was scheduled to be open to the public from October 2016 to March 2017 and it was sponsored in part by, and its items came from the collection of, Milberg himself.

The title “The First Jewish Americans” was intended to have a double meaning: the first Jewish Americans weren’t only from the United States but also from other parts the Americas. The Carvajal booklet fitted the latter meaning. It was an example of Jewish life way before the American Revolution of 1776.

But Milberg was not sure the booklet would be ready for the show. He was involved with lawyers, scholars, and others trying to figure it, first if it was authentic, and second, if his intent at acquiring it didn’t violate any international laws.

Swann Gallery had listed it for $50,000 to $75,000. Again, it described it as a transcription, not the original, dating “not long after Carvajal’s lifetime.” Milberg spotted it and wanted to know if I would recommend that he buy it. Endearingly, to me and others he kept on pronouncing Carvajal’s name “Car-vee-dzal.” My feeling at first was that this might be a replica. Still, I suggested that he proceed with caution, in the unlikely case it was the original. I described to him the scholarly rivalry of del Toro and Nachbin and the disappearance of the booklet and transcriptions of Mexico’s Archivo. I mentioned that, should this be the real thing, I assumed the FBI should be brought in. And then I wondered out loud: what if we are in front of the real McCoy? In that case, I told Milberg he might have inadvertently put his nose into a wasp’s nest. The result could bring about nothing short of an international scandal.

“My immediate reaction was that these books were too good to be true,” Milberg would later state. “I surmised that they were either stolen or fake.”

Within the next half an hour, I shared the Swann Gallery link with a series of colleagues, in Mexico, the United States, and Australia, whose interest in Carvajal had turned them into some kind of secret coterie. Some nurtured a hunch that the Carvajal memoir had finally reemerged. If that was the case, they thought any purchase of it in the United States was unlawful and were eager to contact the Mexican government. Others were more skeptical. A friend of mine, artist Santiago Cohen, like me a Mexican Jew, with whom I had recently collaborated, was in the middle of a graphic novel of his own on Carvajal. He had shown me illustrations he had finished of the 1596 auto-da-fe in Mexico City where Carvajal and his relatives died.

It was a friend and colleague, Barry Carr, a prominent Latin American historian and emeritus professor at La Trobe University, in Melbourne, Australia, who by chance during a lunch at the end of April of 2016, during the PEN International Festival. We had lunch a block away from Cooper Union, in Lower Manhattan. At the time, Carr had mentioned me, a few months prior to the disappearance of the Carvajal booklet from the Archivo, about an enigmatic scholar, possibly Brazilian, who, perhaps because he was kleptomaniac, had stolen a precious treasure from the Mexican national archives.

His last name, he said, was Nachbin.

As it turns out, Carr would play a role in this whole whodunit. He and I met for lunch.

In our conversation, he imagined Nachbin still be alive, which I have never been able to prove. “Definitely material here for a documentary, a novel, and maybe a film,” he said to me.

Etchings by Eko

With Carr as my Virgil, I soon found out that after the incident at the Archivo, Nachbin’s whereabouts become increasingly foggier. By some accounts he might have traveled to Brazil, where he founded and edited a Yiddish newspaper. In other storylines he went to Spain, where he was a newspaper correspondent who wrote on various fronts of the Spanish Civil War until he was killed in one of them. And there are also rumors that he returned to Europe and perished in the Holocaust. “You should write a crónica, Ilan,” said Carr, referring to the long-narrative journalistic genre popular in Latin America.

In all, in spite of Carr’s help, I was never able to find what happened with the Carvajal booklet after 1932. I still don’t know.

Within a matter of days, Starry told me that Milberg had just learned from Swann Gallery that “the Inquisition transcript was sold in London by Bloomsburg in December 2015 and brought 1,000 British pounds. The purchaser is the current seller.” Starry added a bit later: “Where is Umberto Eco when you need him?” (Eco had died in Milan just a few months earlier.)

I reached Carr in Melbourne to tell him what I knew. He was ecstatic with the finding. Carr looked at the whole quest against a larger canvas. “I thought of this repatriation of Mexican patrimonio a few days ago as going through the mountains of correspondence accumulated since 1972,” he said. “La Trobe University, where I taught between 1972 and 2007, at one point held a small but significant collection of pre-Columbian figurines, pottery, and other objects which it acquired (as a gift, I think) from a mining-company executive in Australia who had been a collector. I and my colleagues were not happy about the university’s acceptance. I recall that we found a way to alert the Mexican authorities, via the Mexican embassy in Canberra, the Australian capital, about the existence of these objects. This was back in the early 1990s… The end result was a correct institutional decision to return the materials to Mexico. I have a vivid memory of the little ceremony that was held at La Trobe when the official handover happened. We all felt ‘good’ after the episode.”

Right away, Carr consulted with Anna Lanyon, a former doctoral student he had advised years before. Lanyon was an Australian novelist whose oeuvre often addresses Mexican topics, as is the case of Fire and Song: The Story of Luis de Carvajal and the Mexican Inquisition (2011), which is built as a fictionalized tale of Carvajal and his entourage. She had come across the story in 1994 while she gathered material for another book. “It was the kind of accidental encounter that often happens in archives,” she wrote in the preface. “We may not find what we are looking for, but sometimes we find other treasures instead.”

“I just sent [Lanyon] a link to the auction site,” Carr said to me, “and within fifteen minutes she called me, very excited… She has copies of Luis Carvajal’s handwriting and is also familiar with many of the Inquisition’s scribes who prepared copies of Carvajal’s diary and other documents… [T]he 64,000-peso question is whether the item up for auction is one of the copies made by Inquisition scribes or the original. At first glance, Anna told me (on the phone) that it ‘looked’ like the handwriting of a scribe but she wasn’t too sure and would need to get home and retrieve her copies of Carvajal’ handwriting. So the mystery continues! What happened to the scholar Jacques Nachbin who allegedly removed/stole the original of the diary kept at the Archivo in Mexico City? What happened to him in Spain where he later went as a reporter for a Brazilian Jewish newspaper during the Spanish Civil War (he was never seen again)? Why is an Australian scholar interested? Definitely the stuff of novels!”

In a matter of days, at home with time to ponder, Lanyon wrote back again. The sudden appearance of the documents meant a great deal to her. “I always felt that mote of Luis’s writing would turn up one day,” she stated. “Luis wrote the original in tiny letters in a small black notebook measuring 9 x 15 centimeters (approx. 4 x 6 inches?), while teaching at the Franciscan College of Santiago Tlatelolco between 1590 and 1595,” she wrote. “The photo in the Swann catalogue shows margin notes of the sort the scribes customarily made, so I don’t think this is the original. Also, it appears to be a full-size parchment.” She added: “However, I feel certain that the other two, smaller manuscripts listed are in Luis’s own hand. In February 1595, he gave the Holy Office informer, Luis Díaz, a tiny notebook in which he had copied out the Ten Commandments. The first letters in this book were illuminated, as are the ones in the third item shown in the catalogue. Diaz passed Luis’s gift to the inquisitors. Their scribes would have copied the text of this notebook, but it is most unlikely that they would attempt to reproduce its miniature size or its illuminated letters, so the document in the catalogue is probably the original. (Luis had smuggled it into prison in the taffeta around the brim of his hat—that’s how small it was.)”

Lanyon concluded: “The second item of the three listed is, I think, another of Luis’s tiny devotional notebooks. On 9 February 1595, he instructed Díaz, on his release, to go to the house in Santiago Tlatelolco where the Carvajal family had been living, and retrieve two notebooks hidden there. Luis wanted Díaz to wrap them ‘as if they were a parcel of letters’ and send them to his brothers in Pisa. The inquisitors sent their constable to the house. He found one book—Luis’s memoria—but not the other one. When I wrote my book about Luis de Carvajal, I suggested that one of Luis’s sisters, or a friend, may have already removed it for safe-keeping. It seems possible it could be the second item in the Swann catalogue, although I have no idea how it came to be with the family in Michigan. Luis was a fine Latinist who spent the last five years of his life (prior to his second arrest) translating portions of the scriptures into Spanish for his family and friends, so the content of the two smaller catalogue items fit exactly with this kind of translation work. I’m sure they are his, and feel so excited about them, that I can hardly type these words!”

She subsequently made a point of emphasizing to me that, in her view, the items on sale were not the ones stolen by Nachbin. For her the question was whether Carvajal’s memoir and transcriptions should go back to the Archivo or to Princeton. “The Bancroft has the second trial transcripts of Leonor and Isabel de Carvajal, and also of Luis’s great friend Manuel de Lucena. I believe the Bancroft bought them with the approval of the [Archivo].”

All this to say that the general state of excitement was palpable. I put Lanyon in touch with Starry. And through Starry, I put Milberg in touch with Martin A. Cohen, author of The Martyr.

Cohen only infrequently talked publicly about his research. Still, I thought he needed to know right away about the possible finding of the Carvajal booklet. He preferred phone to email so I called him. In our conversation, he reiterated to me a fact he had mentioned a number of times over the years: while doing the research at the Archivo for his biography The Martyr, he was sure he held in his hand the Carvajal booklet. This is impossible, though. Cohen worked on his biography of Carvajal in the 1950s, a couple of decades after the del Toro-Nachbin feud. If this was the case, then the booklet and transcriptions on sale at the Swann Gallery were inauthentic. The possibility, which is the one I strongly believe, is that Cohen’s memory, as sharp as it is, is misremembering the past.

Although I probed Cohen to test his memory, he never relented. At some point, I decided to give up. Memory is by definition fragile. Guy the Maupassant once said that memory is more perfect than our universe: it gives life where life does not exist.” What we remember is never the past; it is only our memory of the past. Cohen probably browsed through a copy of Carvajal’s manuscript, since one was made before 1932.

At any rate, I told him that the original Carvajal booklet had been found. I asked if, with his permission, I could have Milberg ring him. Cohen complied. He was excited to know that after decades of wandering, the most important text written by a Crypto-Jew in the Americas was now back. “It’s been a kind of bondage,” he said. “Like the wandering of the Israelites for forty years in the desert…”

Ilan Stavans is a Mexican-American essayist, lexicographer, cultural commentator, translator, short-story author and teacher known for his insights into American, Hispanic, and Jewish cultures. He is the author of Quixote (2015) and a contributor to the Norton Anthology of Latino Literature (2010). His Twitter is @IlanStavans

Ilan Stavans is a Mexican-American essayist, lexicographer, cultural commentator, translator, short-story author and teacher known for his insights into American, Hispanic, and Jewish cultures. He is the author of Quixote (2015) and a contributor to the Norton Anthology of Latino Literature (2010). His Twitter is @IlanStavans

©Literal Publishing

Posted: May 23, 2019 at 4:15 pm