The City as Obsessed: Phil Kelly

David Lida

A Paint Reads a City

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

Not long ago, while sitting in an outdoor café a couple of blocks from the Alameda of Santa María la Ribera, painter Phil Kelly heard a scream. It came from a woman sitting at an adjacent table, whose purse had been snatched. Despite the fact that Kelly has not enjoyed the best of health in recent years, he decided to rally and give chase.

“I got halfway down the street and was catching up to the guy,” says the painter with a complacent smile. “He took out a gun and began to shoot at me. Luckily, he wasn’t a very good shot.” At that point, Kelly thought it prudent to fi nd the nearest corner as quickly as possible, and turn it.

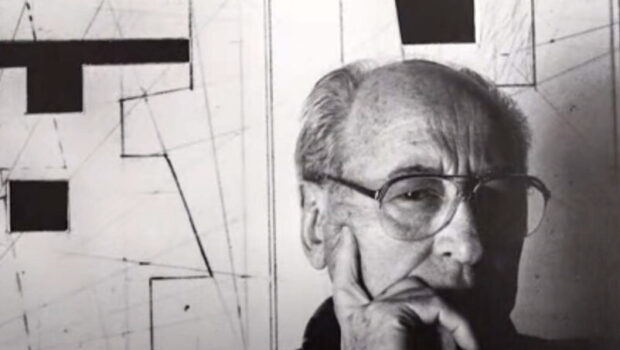

The understated insouciance with which Kelly describes this incident is typical of his subtle, charming and often enigmatic sense of humor. The artist is an Irishman raised in England who came to Mexico City in the early 1980s and became nationalized in 1994. But that sentence doesn’t even begin to explain the artist’s relationship with the city where he found not only a home but a theme for his work, a public that responds to it, a wife and a family.

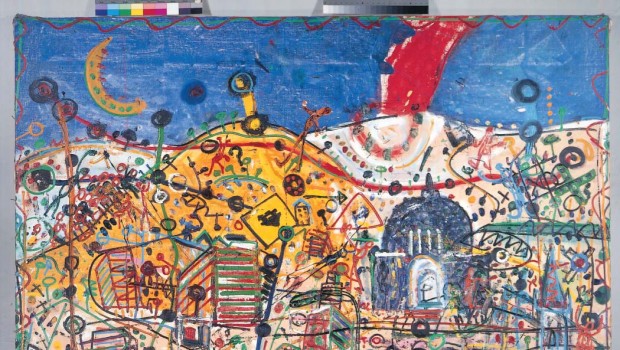

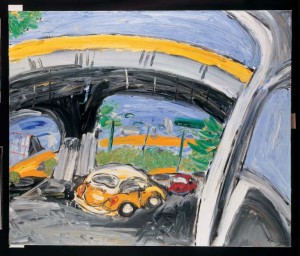

Kelly, 58, is bald with a pate the color of raw veal. He tends to dress in clothes stained with all the colors of the rainbow, mismatched socks and heavy black shoes, also blemished with paint. His impressionist canvases absorb the chaos of the city and somehow make it attractive–a huge sky of toxic beige (or pink or orange), the speeding crowds around boulevards and monuments like the Angel of Independence, Paseo de la Reforma, or the Torre Mayor. Here and there will be the yellow barriers of the Circuito Interior, a Volkswagen taxi, a tree asphyxiated by smog. The artist is also known to paint places as diverse as the desert in Hermosillo, Dublin’s River Liffey or the Hotel De Ville in Paris. But there is no doubt that his greatest and most constant inspiration has been Mexico City.

The painter has often said that he arrived here with fifty dollars in his pocket, half of which he spent on a hotel room. Once ensconced in these quarters, he opened the Yellow Pages and searched for schools that taught English. By the end of the day, he had not only a job but an apartment, as one of the other teachers was looking for a roommate.

Already fluent in English and French, at the time Kelly spoke no Spanish, so he began a process that he describes as “reading the city.” He explains that he worked long hours, giving classes in the remotest parts of the urban sprawl. “I walked, I traveled by metro or combi, I went all over town to the places no one else wanted to go. And I began to read the streets. The physical way in which people existed day by day. The yellow taxis and the palm trees were obsessions, emblems that for me reflected the exuberance and the freshness of the city.”

It would take years of struggle before Kelly found success. Indeed, the painter, now fifty-eight, was close to forty before he began to eke out a living from his work. He had so many temporary jobs on the road to accomplishment– including milkman, truck driver, and movie extra–that he probably doesn’t even remember all of them.

Today, he sells as many paintings as he can produce–and he is very productive. In November he will have an exhibition at the art gallery at UAM Azcapotzalco, to celebrate the thirty-fifth anniversary of the university and the tenth of the gallery. Although he is represented by no gallery in Mexico City–his wife, Ruth Munguía, handles the business aspect of his work–he has exhibited all over the city, including solo shows in El Museo de Arte Moderno and El Museo de la Ciudad de México. (He is represented by galleries in London and Dublin.)

While Kelly’s standard canvas measures about one meter by 1.20, lately, he has been commissioned to work in larger formats– with dimensions as large as 300 cm by 500 cm–for diverse clients, including restaurants, hotels and government offices. “There is an increasing awareness that painting works well in these places,” says the artist. “Like in Ireland or in Europe, it’s becoming part of the budget when they build a new building. The constructors figure it into the costs. They are putting a minimum amount into real painting and not an inexpensive print of a Barbie doll,” he adds, offering a direct gibe to the conceptual art that has been so popular in Mexico City in recent years, and which has left him unimpressed.

When working on large canvases, he tapes a brush to the end of the pole of a broom to get to the highest parts. “You could probably spend a lot of money on expensive brushes if you wanted to,” he says. For the lowest parts, he says, “I just lean down as if I were cleaning a toilet.”

Recently, Kelly has suffered from various ailments including hepatitis and liver disease, unrelieved by a lifetime of heavy drinking. One of the complications is that it has become more difficult for him to get around the city, and to the cantinas that served as a constant inspiration. The danger, he admits, is that “we become less receptive, we get stale or old. Since I can’t walk so much as before, the process of osmosis, of picking up things wherever you go, is more limited.

“I can’t stop off at bars like I used to. And even if I wanted to, so many places where I used to go don’t exist any longer.” He mentions El Nivel, the cantina with the oldest license in Mexico City, which closed its doors in 2007, as “a focal point.”

“I used to show up there, after walking from the house, at eleven in the morning or perhaps a little later, not long after they’d opened up. There was hardly anyone there. I would sit in the corner and draw and talk to the waiters, who would try to force huge botanas on me. They would always ask me to show them my socks. It was like a ritual.

“You can’t be a painter if you’re not curious about your surroundings. What I very consciously try to do is to fi nd something every day. The color of a truck. The way that someone crosses the street. The garbage trucks, two in a row going down the boulevard. Or the steam coming from a vat of tamales.”

His current challenges are perhaps par for the course for a life that was mostly spent struggling. “Getting there was so hard,” he says. “I had this incredible drive, almost an obsession. Life is so impossible. Everybody, especially the Brits, are terrible. My father and my schoolteachers all said I would be a failure and I would never make it. My father said I wouldn’t be a painter, that I would be a drunk on the street corner. So I said, ‘ok, bye bye.’ I did anything and everything for survival.”

“I could never have done advanced degrees. I was too intent to get on and do it. If you need to learn, there are always museums and books. And you can find painters you admire and knock on their doors and ask them how they do it.”

Posted: April 18, 2012 at 9:46 pm