The Collective Memory

Una conversación con Emilio Chapela

Rose Mary Salum

Download Complete PDF / Descargar

Rose Mary Salum: You are young and yet, your work has been exhibited in museums and has the recognition of curators and art collectors. Can you tell our readers about your proposal?

Emilio Chapela: I started doing artwork as a photographer, but quite soon I felt the necessity to explore different media that seemed to work better for my interests at the time. Quite soon, I started moving towards video, painting, drawing, etc. I became interested in the communication processes, language and the tools with which it’s supported: Internet, books, dictionaries, etc.

RMS: Your work shows an intimate connection with the Internet world, specifically your series Ask Google. Can you tell us why?

EM: The Internet changes every second because its users are constantly building it. It is like a big mirror: If we move, the reflection follows. But in this case, it leaves a trail. I am interested in directing the attention to some of those traces that evidence how a group of people think about certain matters. It is like a glimpse into the collective unconsciousness.

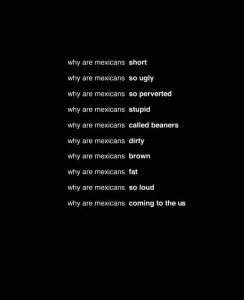

Ask Google consists of a series of text-works based on search suggestions–prompted by Google–which are the most popular queries at any given time. It is shocking to discover what people search on the Internet when nobody is looking. Anonymity is a very powerful thing; but so is freedom of speech. In a more recent piece called Mexicans, I show all the tweets (as they happen) that contain the word “Mexicans” in the body of the text. The result is a constant cascade of racist comments, prejudices and aggressions towards Mexicans. All signed by the authors.

RMS: This is a fascinating idea. You make it look like the Internet has so many layers of interpretation, like the human mind does, or a piece of art. By working with that subject, you are unveiling what Jung called the collective unconscious. Can you elaborate on that?

EM: Absolutely, Marshall McLuhan said that technology was an extension of ourselves; “The medium is the message,” he said. And the Internet is no exception. It is an extension of our mind that inherits its complexity. Not only that, it is also a refl ection of the collective since it is built horizontally by millions of users. The Internet is an extension of all of them.

I think Carl Jung talked about the collective unconsciousness in a more primitive way; he said that it was possible to dream about the sea without ever seeing it before. I really like this idea, but nowadays it is potentially possible to have access to every picture of the sea ever posted on the Internet. This is very powerful.

RMS: Hello Chicago is at the same time playful and philosophical because it deals with the eternal problem of knowledge. Not even the machines could interpret that for which they were made.

EM: Computers are incapable of interpretation; this is something that interests me a lot. We make extraordinary efforts to “teach” computers how to interpret just to watch them fail. I find this beautiful. There are many accurate and efficient approximations to computer interpretation or translation. But it is essentially impossible to achieve. Hello Chicago speaks about this impossibility, but it is also about humor. Political speeches are about control and all words are selected very carefully. Processing Obama’s inaugural speech through a voice to text application gives place to unwanted accidents, glitches and humor.

RMS: You force the spectator to question whether communication is even possible, static or dynamic.

EM: For me, it is very important to talk about communication in terms of miscommunication. But that does not make the phenomenon static. There is a lot of exchange when we fail to communicate. I like to think that my work deals with the deconstruction of language, more than simply nonsense. The metaphor is another fi gure that interests me a lot. Being precise in the wording while motivating different interpretations. This is something very present in my Google translation pieces.

RMS: Yes, it shows. The metaphor adds to the meaning of your pieces. It seems to me that you are dealing with the most fundamental questions in philosophy. Even the philosophers of language worked with the deconstruction of language.

EM: Interpretation is a key aspect of the metaphor. And also of translation. But when a computer that is incapable of interpretation is in charge of translating, things get more playful and confusing. Messages get truncated. I like this. Ambiguity can be a great starting point for meaningful metaphors.

RMS: It seems to me as if you were using the scientific method to obtain mathematical answers through your art.

EM: Mathematics are very important in my work but not in a literal level. I’m interested in asking questions that are relevant to science, but from the point of view of an artist. I tend to be analytical on how I conceptualize my pieces, but I’m very concerned with beauty, social responsibility and criticism as well. I do not think art has such a strong responsibility towards truth as toward science. This is great because it gives you more freedom. Pursuing the truth is a really complicated matter and can be restraining at times.

RMS: And yet you are concerned with social responsibility like no other artist of your generation. That is a disjunctive that has been around for so many years. How can art take on that responsibility?

EM: I do not think that is possible to say that my work has less or more responsibility than that of other artists. I think that art becomes social and political by the simple act of showing it inside a gallery or a Museum. But this does not mean that the work is about politics or social awareness. I feel a responsibility to speak about the things that I like and think. This the type of social awareness and responsibility that interests me. It’s more basic. However, I have been advised recently not to show some of my pieces that speak about how Mexicans are perceived in other parts of the world. It seems that there is governmental policy concerned with improving our image as a country even at the cost of freedom of speech. Teresa Margolles knows this better than anyone. However, they have it all wrong. We have to show these things, not hide them.

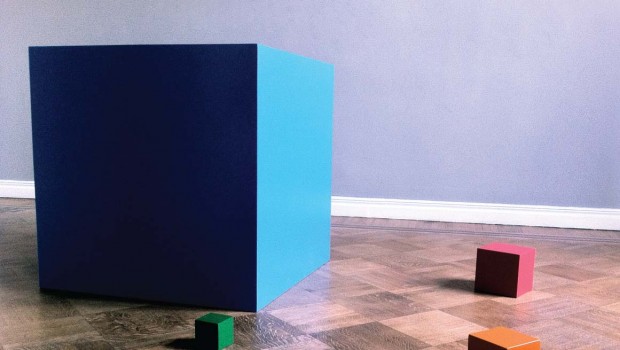

RMS: Your series Corporate Logos is an experiment that relates to the globalized world, the economy, and the collective unconscious. However,

what results is abstract art. Can you elaborate on this subject?

EM: I am interested in abstraction in terms of determination. The combination of colors and the proportions for each of these paintings is not decided by me, it is determined by a series of decisions made by marketing, psychology and advertising specialists. I do not have control of the final outcome. This strategy moves in an opposite direction than that of artists like Ellsworth Kelly or Joseph Albers: Their work is about control and perception, while mine is about predetermination.

Corporate Logos are part of our visual landscape and they stay fixed in our minds, I am interested in triggering the collective memory in such a way that the logos become partly recognizable but remain abstract (and anonymous) at the same time.

RMS: You are in Berlin. Are you working on a new project?

EM: At the moment I am working on a project that is called Die Kurt F. Gödel Bibliothek , that consists of a library that will hold thousands of books made entirely out of wood. No book will be written or read, they only will be named. To follow the progress of this project visit kgbibliothek.blogspot.com.

Rose Mary Salum is the founder and director of Literal, Latin American Voices. She´s the author of Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) among other titles.

Rose Mary Salum is the founder and director of Literal, Latin American Voices. She´s the author of Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing, 2013) among other titles.

Rose Mary Salum: Eres joven y, sin embargo, tu trabajo ha sido exhibido en varios museos y cuenta con el reconocimiento de curadores y coleccionistas de arte. ¿Puedes hablarnos acerca de tu trabajo?

Emilio Chapela: Empecé como fotógrafo pero muy pronto sentí la necesidad de explorar diferentes medios que en ese momento parecieron

adaptarse mejor a mis intereses. Me pasé al video, la pintura y el dibujo. Me interesé asimismo en los procesos de comunicación, en el lenguaje y las herramientas que le son afines: internet, libros, diccionarios, etc.

RMS: Tu trabajo muestra una íntima conexión con el mundo de internet, en concreto tu serie Ask Google.

EM: Internet cambia cada segundo porque sus usuarios están participando constantemente. Es como un gran espejo: si nos movemos,

el reflejo nos sigue. Aunque, en este caso, queda un rastro. En tal sentido me interesa dirigir la atención hacia algunas de esas huellas que ponen en evidencia lo que cierto grupo de personas piensa sobre determinados asuntos. Es como una visión del inconsciente colectivo. Ask Google consiste en una serie de obras a partir de textworks de búsqueda vía Google, sobre la base de las consultas más populares en un momento dado. Es sorprendente descubrir lo que la gente indaga en internet cuando nadie la está mirando. El anonimato es una cosa muy poderosa lo mismo que la libertad de expresión. En una pieza reciente llamada Mexicanos, muestro todos los tweets con la palabra “mexicanos” (tal y como suceden) en el cuerpo del texto. El resultado es una cascada constante de comentarios racistas, de prejuicios y de agresiones a los mexicanos. Y todos firmados por sus autores.

RMS: Esto es muy interesante. Tú logras que internet tenga muchos niveles de interpretación, igual que en la mente humana o en la obra de arte. Al trabajar con ese material ilumina lo que Jung llamó el inconsciente colectivo. ¿Puedes abundar al respecto?

EM: Por supuesto. Marshall McLuhan señaló que la tecnología es una extensión de nosotros mismos: “El medio es el mensaje”. E internet

no es una excepción. Se trata de una extensión de nuestra mente que hereda su complejidad. No sólo eso, también es un refl ejo de la colectividad ya que está constituido por un horizonte de millones de usuarios. Internet es una extensión de todos ellos. Creo que Carl Jung hablaba del inconsciente colectivo de una manera más primigenia: decía que era posible soñar con el mar sin haberlo visto. La idea me gusta mucho. Hoy es potencialmente factible acceder a todas las imágenes del mar posteadas alguna vez en internet. Esto es muy poderoso. He estado trabajando en piezas a partir de imágenes y animación en videos bajados de internet, como Gun from the Google, que muestra cientos de fotos de armas de fuego que centellean velozmente frente a nosotros, cada vez de mayor poder y calibre. Es muy aterrador pensar sobre este video en términos del inconsciente colectivo y lo que ello sugiere.

RMS: Hello Chicago es una obra a la vez lúdica y filosófica, que tiene que ver con el eterno problema del conocimiento. Ni siquiera las máquinas podrían desentrañar el para qué fueron hechas.

EM: Las computadoras son incapaces de interpretación, esto es algo que me interesa mucho. Hacemos un esfuerzo extraordinario para “enseñarles” a interpretar sólo para verlas fallar. Pero me parece hermoso. Hay muchas aproximaciones precisas y efi cientes a la interpretación o traducción informática. Sin embargo, en esencia se trata de un imposible. Hello Chicago habla de esta imposibilidad aunque

tratada con humor. Los discursos políticos están hipercontrolados y todas las palabras se eligen con muchísimo cuidado. El discurso inaugural de Obama pasado a través de un procesador de voz a texto da lugar a incidentes inesperados, a fallas técnicas cargadas de humor.

RMS: Obliga al espectador a preguntase a sí mismo si la comunicación aún es posible, dinámica o pasivamente.

EM: Para mí es muy importante hablar de comunicación en términos de falta de comunicación. Pero eso no la convierte en un fenómeno

estático. Hay un montón de intercambio cuando no somos capaces de comunicarnos. Me gusta pensar que mi obra ofrece cierta deconstrucción del lenguaje más que un simple sinsentido. La metáfora es otra fi gura que me interesa mucho, en tanto que es precisamente

la palabra la que motiva diferentes interpretaciones. Estas cosas están presentes en mis piezas de traducción de Google.

RMS: Sí, se nota. Las metáforas publicitarias según el significado de sus piezas. A mí me parece que se trata de cuestiones fundamentales

de la filosofía. Incluso los fi lósofos del lenguaje trabajan con la deconstrucción del lenguaje.

EM: La interpretación es un aspecto clave de la metáfora. Y también la traducción. Pero cuando una computadora incapaz de interpretar está a cargo de la traducción las cosas se ponen más bien chuscas y confusas. Los mensajes se truncan. Esto me gusta. La ambigüedad puede ser un excelente punto de partida para metáforas signifi cativas.

RMS: A mí me parece como si emplearas el método científico para obtener una respuesta matemática en tu obra.

EM: Las matemáticas son muy importantes en mi trabajo, pero no en un nivel literal. Estoy interesado en hacer preguntas que son relevantes para la ciencia pero desde el punto de vista de un artista. Tiendo a ser analítico sobre cómo conceptualizar mis piezas, aunque también estoy muy comprometido con la belleza, con la crítica y la responsabilidad social. No creo que el arte tenga una gran responsabilidad con la verdad como la ciencia. Esto es muy bueno porque le da más libertad. La búsqueda de la verdad es un asunto muy complicado y puede limitar tu tiempo.

RMS: Y sin embargo, apelas a la responsabilidad social como ningún otro artista de tu generación. Esta es una disyuntiva que ha existido

durante muchos años: ¿puede el arte asumir esa responsabilidad?

EM: No creo que se pueda decir que mi trabajo tiene mayor o menor responsabilidad que el de otros artistas. El arte se convierte en social y político por el simple hecho de mostrarse dentro de una galería o museo. Pero esto no quiere decir que dicho trabajo trate de política o de conciencia social. Siento la responsabilidad de hablar sobre las cosas que me gustan y creo. Esta es la conciencia social y la responsabilidad

que me interesa. Es más elemental. Sin embargo, he recibido recientemente la sugerencia de no mostrar algunas de mis piezas que hablan sobre cómo se perciben los mexicanos en otras partes del mundo. Pareciera que existe una política gubernamental sobre el mejoramiento

de nuestra imagen como país a costa de la libertad de expresión. Teresa Margolles lo sabe mejor que nadie. Sin embargo, todo eso está mal. Nosotros tenemos que mostrar estas cosas, no ocultarlas.

RMS: Tu serie Corporate Logos es un experimento relacionado con el mundo globalizado, con la economía y el inconsciente colectivo, pero

los resultados son un arte abstracto ¿Puedes hablarnos al respecto?

EM: Me interesa la abstracción en términos de determinación. La combinación de colores y las proporciones para cada una de estas pinturas no fue decidida por mí: estuvo determinada por una serie dictada según el marketing, la psicología y los especialistas en publicidad. No

tengo control sobre el resultado fi nal. Esta estrategia se mueve en una dirección opuesta a la de artistas como Ellsworth Kelly y Joseph Albers: su trabajo ha sido en torno al control y la percepción artísticas mientras que el mío es sobre la pre-determinación. Los logos corporativos son parte de nuestro paisaje visual y se quedan fi jos en nuestra mente. Estoy interesado en el desencadenamiento de la memoria colectiva de tal forma que los logotipos se conviertan en partes reconocibles pero siguen siendo abstractos (y anónimos) al mismo tiempo.

RMS: ¿Estás trabajando en Berlín en un nuevo proyecto?

EM: Realizo un proyecto que se llama Die Kurt F. Gödel Bibliothek, que consiste en una biblioteca con miles de libros hechos enteramente

de madera. No hay ningún libro para escribir o leer, sólo el nombre. Se puede dar seguimiento a este trabajo en kgbibliothek.blogspot.com.

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto 2015) y Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing 2013) entre otros títulos.. Su twitter @rosemarysalum

Rose Mary Salum es la fundadora y directora de Literal, Latin American Voices. Es la autora de El agua que mece el silencio (Vaso Roto 2015) y Delta de las arenas, cuentos árabes, cuentos judíos (Literal Publishing 2013) entre otros títulos.. Su twitter @rosemarysalum

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.