Traces of a Forest

Indicios de un bosque

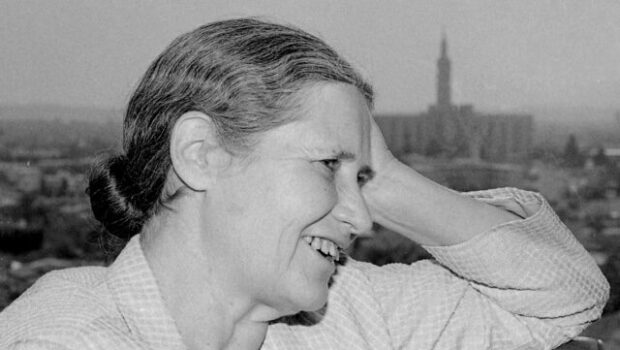

Olivia Teroba

You can see a sleeping volcano from anywhere in the city where I was born. It’s dormant, people say: its most recent eruption was 3000 years ago. Many think it’s a mountain, ignoring the magma crust throughout a steady calm. Long ago, it was called Matlalcueitl: the name of a deity associated with Tláloc and the worship of water. To avoid indulging this paganism, the Spaniards christened it the Sierra de Tlaxcala. But divine memories led the Tlaxcaltecas to call it “Malinche.”

Our volcano was once blanketed with woods. Down below, there were oaks; higher up, pines and oyamels; at the top, pasture. It’s deforested now.

Malinche was the first translator in the Spanish-speaking Americas. She, too, had several names throughout her life. Her parents named her Malinalli, after the goddess of herbs. Later, when she was sold as a slave, she became Malintzin: noble prisoner. When she and nineteen other women were handed over to Hernán Cortés, she was declared Marina.

The oldest geological structure in the state of Tlaxcala has a woman’s name.

Today, women from my city are still seen as exchangeable goods. As merchandise. And so, along the highway that connects us to the neighboring state, there are several towns famous for their lenones: men who force women to become sex workers. It’s called human trafficking.

As it turns out, Marina had a knack for languages. She knew Maya and Náhuatl and was quick to learn Spanish. I imagine her as an intensely brown-skinned woman, her gestures agile, her hair long and black, her eyes dark and intelligent. Quiet, listening to the foreigners as they spoke. Learning another language to survive. Adapting to survive. Teaching Cortés the indigenous ways and customs. Warning him of an ambush plotted by an enemy people. Negotiating on behalf of the Spaniards.

Some romantic fictions say that Marina fell in love with Cortés.

Or they defend her, claiming that she wanted to free indigenous communities from Aztec control.

Her name became an insult: being malinchista means preferring what comes from elsewhere.

She is seen as the ultimate perpetrator, the agent responsible for Spanish conquest and colonization.

In the codices, Córtes is never depicted without Marina beside him. But sometimes she appears alone, addressing an entire village. She abetted many indigenous conversions to the Catholic faith.

People blame a 27-year-old woman for a massacre. Even though she never touched a weapon. They don’t blame anyone who delivered her to a group of gold- and power-hungry strangers.

Or the indigenous hierarchies, locked in violent territorial struggle for hundreds of years.

It was her fault, they say.

It’s always a woman’s fault.

The place I come from is coated in concrete and surrounded by mountains. A dirty river runs through it. But neither cars nor malls can hide the traces of the forest that once stood there. For example, the biting night wind. The same cold you can feel on the slopes of the Malinche, the birthplace of every sunrise. A dormant volcano is a reminder: The worst betrayal is to hate yourself. The color of your skin, the words you speak, your own way of being a woman. Anzaldúa says so: “Not me sold out my people but they me.”

*This text was written during the creative writing program Under the Volcano, which the author attended as a recipient of the La Página Dorada fellowship.

Olivia Teroba (Tlaxcala, 1988). Writer and editor. Her first book, Un lugar seguro, was published in 2019 by Paraíso Perdido (Mexico). She studied communications and literature. She has received fellowships from various writing programs—such as the Fundación para las Letras Mexicanas, FONCA, and Under the Volcano—and has won several awards for her work. She currently lives in Mexico City, where she freelances, reads astrological carts, and is a member of the publishing project Osa Menor.

Olivia Teroba (Tlaxcala, 1988). Writer and editor. Her first book, Un lugar seguro, was published in 2019 by Paraíso Perdido (Mexico). She studied communications and literature. She has received fellowships from various writing programs—such as the Fundación para las Letras Mexicanas, FONCA, and Under the Volcano—and has won several awards for her work. She currently lives in Mexico City, where she freelances, reads astrological carts, and is a member of the publishing project Osa Menor.

Robin Myers, poet and translator, grew up in the United States and lives in Mexico City. She was among the winners of the 2019 Poem in Translation Contest held by Words Without Borders and the Academy of American Poets. Recent or forthcoming translations include books by Cristina Rivera Garza, Mónica Ramón Ríos, Gloria Susana Esquivel, Isabel Zapata, Juana Adcock, Aurelia Cortés Peyrón, and Ezequiel Zaidenwerg.

Robin Myers, poet and translator, grew up in the United States and lives in Mexico City. She was among the winners of the 2019 Poem in Translation Contest held by Words Without Borders and the Academy of American Poets. Recent or forthcoming translations include books by Cristina Rivera Garza, Mónica Ramón Ríos, Gloria Susana Esquivel, Isabel Zapata, Juana Adcock, Aurelia Cortés Peyrón, and Ezequiel Zaidenwerg.

Hay un volcán dormido que se alcanza a ver desde cualquier punto de mi ciudad de origen. Dicen que está apagado; su explosión más reciente fue hace 3000 años. Mucha gente piensa que es un monte. Su cubierta de magma es ignorada debido a su persistente calma. Hace mucho se llamaba Matlalcueitl: nombre de una deidad asociada a Tláloc y al culto al agua. Para evitar este paganismo, los españoles lo denominaron Sierra de Tlaxcala. Pero las reminiscencias divinas llevaron a los tlaxcaltecas a decirle “Malinche”.

Nuestro volcán estuvo cubierto de bosque. En la parte más baja había encinos, más arriba pinos y oyameles, en lo alto, pastizales. Ahora está deforestado.

Malinche fue la primera traductora de la América hispana. A lo largo de su vida, ella también tuvo varios nombres. Sus padres le pusieron Malinalli, nombre de una diosa de la hierba. Después, cuando fue vendida como esclava, fue Malintzin: prisionera noble. Cuando la entregaron, junto con otras diecinueve mujeres, a Hernán Cortés, su nombre cambió a Marina.

La estructura geológica más grande en Tlaxcala tiene el nombre de una mujer.

Hasta la fecha, las mujeres en mi localidad siguen siendo vistas como objetos de cambio. Como mercancía. Por eso, a lo largo de la carretera que nos une con el estado vecino, se encuentran varios pueblos famosos por sus lenones: hombres que obligan a mujeres a ser trabajadoras sexuales. Se llama trata de personas.

Resulta que a Marina se le facilitaban los idiomas. Sabía maya, náhuatl, y aprendió español en poco tiempo. Me la imagino como una mujer intensamente morena, de movimientos ágiles, pelo largo y negro, ojos oscuros y mirada inteligente. Me la imagino callada, escuchando las palabras de los extranjeros. Aprendiendo otro idioma para sobrevivir. Adaptándose para sobrevivir. Mostrando a Cortés las costumbres y las maneras de los pueblos indígenas. Advirtiendo de una emboscada planeada por un pueblo enemigo. Negociando en nombre de los españoles.

Algunas ficciones románticas dicen que Marina se enamoró de Cortés.

O la justifican, diciendo que ella quería liberar a varios pueblos indígenas del yugo de los aztecas.

Su nombre se volvió un adjetivo peyorativo: ser malinchista es preferir lo que viene de afuera.

Ella es considerada la culpable por excelencia de la conquista y colonización española.

En los códices, no hay figura de Cortés que aparezca sin Marina. Pero a veces aparece ella sola, hablando a un pueblo entero. Ella convirtió a muchos indígenas a la religión católica.

Culpan a una mujer de 27 años de una masacre. Aunque sus manos nunca tocaron un arma. No culpan a quienes la entregaron a unos extraños ansiosos de oro y poder.

Ni a las jerarquías indígenas, enfrascadas en una violenta lucha por territorios desde hacía cientos de años.

Ella tuvo la culpa, dicen.

Una mujer siempre tiene la culpa.

El lugar de donde vengo está cubierto de pavimento y rodeado de monte. Lo atraviesa un río sucio. Pero ni los autos ni los centros comerciales ocultan los indicios de que alguna vez ahí hubo un bosque. Por ejemplo, el viento helado en las noches. El mismo frío que hace en la Malinche, el lugar desde donde sale el sol todos los días. El volcán dormido es un recordatorio: La peor traición es odiarte a ti misma. Al color de tu piel, a tu manera de ser mujer, a las palabras que salen de tu boca. Lo escribió Anzaldúa: “Yo no vendí a mi gente. Mi gente me vendió a mí”.

*Este texto fue escrito durante el programa de escritura creativa Under the Volcano, al que asistí gracias a la beca La Página Dorada.

Olivia Teroba (Tlaxcala, 1988). Escritora y editora. Su primer libro Un lugar seguro, fue publicado en 2019 por Paraíso Perdido. Estudió Comunicación y Letras. Ha sido becaria de diversos programas de escritura, como la Fundación para las Letras Mexicanas, el FONCA y Under the Volcano. Ha ganado algunos premios por sus escritos. Actualmente vive en la Ciudad de México, donde trabaja como freelance, hace cartas astrales, y forma parte del proyecto editorial Osa Menor.

Olivia Teroba (Tlaxcala, 1988). Escritora y editora. Su primer libro Un lugar seguro, fue publicado en 2019 por Paraíso Perdido. Estudió Comunicación y Letras. Ha sido becaria de diversos programas de escritura, como la Fundación para las Letras Mexicanas, el FONCA y Under the Volcano. Ha ganado algunos premios por sus escritos. Actualmente vive en la Ciudad de México, donde trabaja como freelance, hace cartas astrales, y forma parte del proyecto editorial Osa Menor.