UTOPIAS AND FAREWELLS

Rafael Rojas

Translated by Tanya Huntington

I

In her well-known study, the scholar Rachel Weiss proposes that contemporary art in Cuba be understood as a voyage to and from utopia. The timeline of Weiss’ study encompasses the 1980s and the first decade of the new millennium, or between Volume One and the installations Pure Formality and Apolitical, projects created by Fernando Rodríguez and Wilfredo Prieto for the first Havana Biennials of the 21st century. It became evident from the title of the volume that an accessible definition of the concept of utopia would be employed, postulating new contemporary art in Cuba since the 1980s as an attempt to return to the original utopianism of the Cuban Revolution through the visual arts.

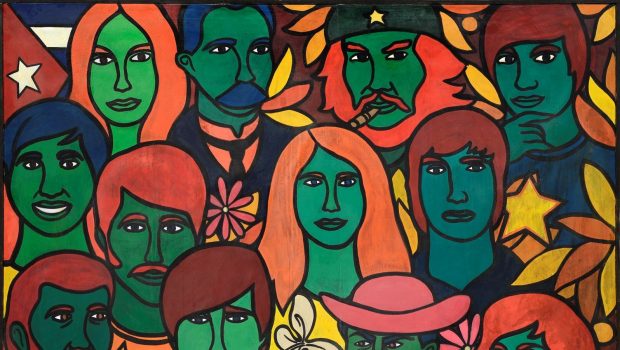

But utopia was also something more, according to the visual poetics of Flavor Garciandía and Juan Francisco Elso Padilla, José Bedia and Gustavo Pérez Monzón, or the montages of the group Puré, or the hearts, minds, and mugs of Segundo Planes and Tomás Esson, or the Maoist panels of Glexis Novoa or, more literally, the Fidels and Che Guevaras of Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas, Tomás Esson, Alejandro Aguilera, Arturo Cuenca, René Francisco, Eduardo Ponjuán, and José Ángel Toirac. The utopia of Cuban art had to do with the conquest of autonomy or a place of self-declaration, one that would allow for the representation of the political without abandoning the aesthetic terrain.

Sandu Darié, Sin título (Untitled), c. 1960–70, tempera on canvas, Ella Fontanals-Cisneros Collection, Miami.

That cultural revolt of the 80s fractured the official narrative of Cuban art history. Up until then, the visual arts narrative was sustained by the notion of an extended 1920s and 30s avant-gardism, capable of dodging periodic ruptures in the island’s cultural past. Such was the deceptive “mid-century rise,” formulated by Alejo Carpentier in 1977 and repeated by so many others, that led to an understanding of the Cuban Revolution and its cultural politics as an eternally renovated present tense. “Revolutionary” art, according to that narrative, had finally overcome all possible conflicts “of form or content.”

Already in a previous book, New Art of Cuba (1994), Luis Camnitzer had observed that rupture with the ideological realism of the 70s had reconnected the artists of the 80s with generations from the 50s and 60s, thus shaking the doctrinal foundations of the Revolution’s cultural policies. Weiss continued to elaborate this observation by documenting –albeit partially–multiple cases of censorship that marked the breakout of art in the 80s. From Volume One to the Castillo de la Real Fuerza project, visual arts made advances during the 80s despite constant episodes of censorship that reflected, in turn, an institutional resistance and learning process.

Adiós Utopia. Art in Cuba since 1950, the recent exhibition mounted by the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston presents yet another exploration of art and utopia in post-revolutionary Cuba. The show bears witness to the fact that the idea of Cuban art history having been rewritten as a result, to a large degree, of the 80s rebellion is now a given. Curators René Francisco, Gerardo Mosquera, and Elsa Vega propose as a point of departure the contemporary relationship between visual texts and utopian discourse in the 1950s, before the triumph of the Revolution in 1959, something not so clearly evident in artists from the catalog such as Antonio Eligio Tonel, Iván de la Nuez, or Rachel Weiss herself. The texts written by Elsa Vega, Gerardo Mosquera, René Francisco highlight this major shift in the historization of Cuban art.

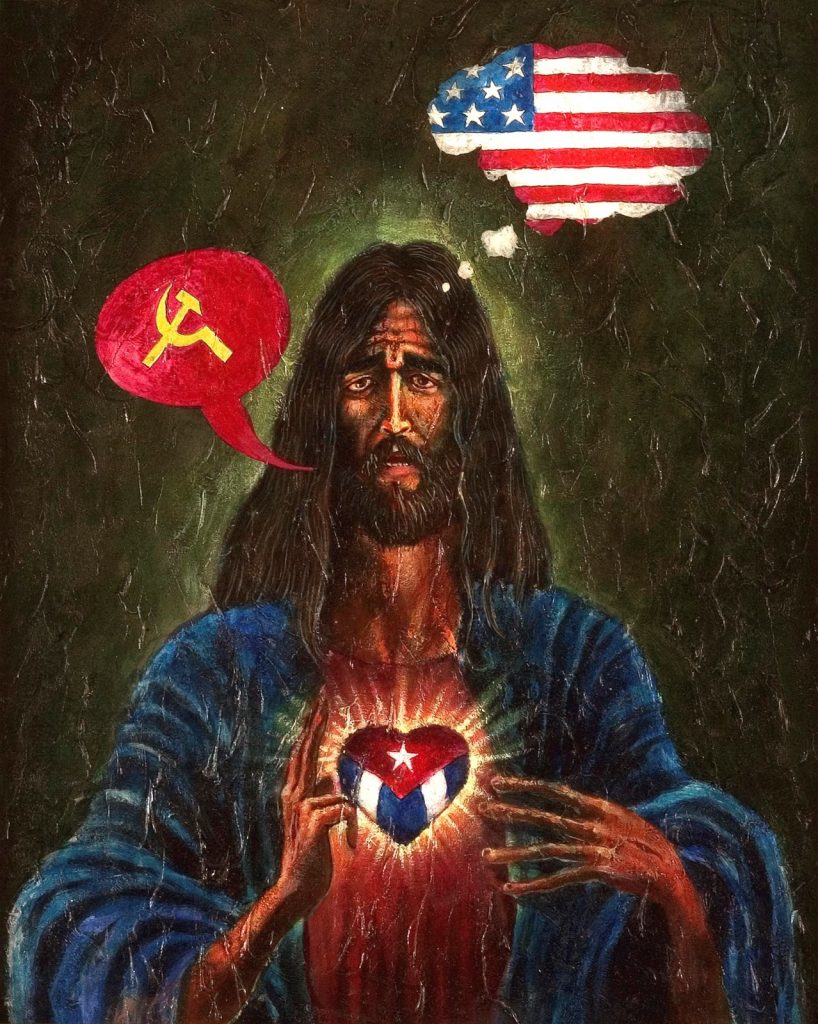

Lázaro Saavedra, El Sagrado Corazón (Sacred Heart), 1995, acrylic on board, Patricia & Howard Farber Collection, New York. © Lázaro Saavedra

Herein lies a disengagement between curatorial focus and critical texts that merits debate. The curators have called upon us to recognize the origin of artistic utopias in the empowerment of visual language produced in the 1950s by the abstract, geometric, and concrete art of the Eleven or rather, the Ten: Mario Carreño and Rafael Soriano, Loló Soldevilla and Pedro de Oraá, Carmen Herrera and Pedro Álvarez, Sandú Darié and José Mijares –whereas critics persist in defining the original connection to utopia as the visual imprint left on art by the 1959 Revolution. In a recent study, Abigail McEwen reinforces the curatorial thesis of Adiós Utopia by observing the projection of an “avant-garde horizon” onto the art of the 50s that generated dilemmas of assumption and rejection within early revolutionary cultural policy.

Nor does the contextualist critical perspective have much to say about the utopia personified by the Revolution, or about the kind of utopian representation it inspired in art. Antonio Eligio Tonel quotes Ernst Bloch, Martin Buber, and Karl Mannheim –the latter indirectly, through Paul Ricoeur– however, in addition to having elaborated their reflections on utopia before the Cold War, all three gave it different connotations. Buber, for example, distinguished two eschatologies in utopian thought: the prophetic and the apocalyptic. Which of the two is dominant in Cuban utopianism? Or are they one and the same? While it is true that Mannheim was opposed to any facile identification of the utopian with the impossible, as sustained by Marxist or Positivist scientism, his critique parallels the libertarian socialism of Landauer and the Hegelianism of Droysen, thus distancing him from any of the two theories of socialist transition that disputed the ideological field of the 60s in Cuba: the Guevarist and the Soviet.

In order to rethink the Cuban experience, more pertinent than any of these authors would be others closer to the New Left, such as Herbert Marcuse or Theodore Roszak, or Caribbean Marxists with a clear attachment to the egalitarian or pro-sovereign traditions of the region, such as C. L. R. James or Eric Williams. There is, in fact, an intellectual utopianism in Cuba that predates the Revolution, the best of which approached the island within its Latin American and Caribbean surroundings, as can be read in The Kingdom of This World (1949) by Alejo Carpentier, Dialogues about Destiny (1954) by Gustavo Pittaluga, or American Expression (1954) by José Lezama Lima. This was an ideologically plural utopianism given that, as Buber and Mannheim observed, ever since Sir Thomas More, utopia has simultaneously formed part of various philosophical traditions.

Raúl Martínez, 9 Repeticiones del Fidel con Micrófono (9 Repetitions of Fidel with a Microphone), 1968, oil on canvas, Col. Wallace Campbell, Jamaica. © Archivo Raúl Martínez

Indeed, Cuban utopianism predates the Revolution considerably, but beyond a doubt, in any of its three connotations as ideal society, impossible harmony, or authoritarian state, it is rooted in the culture of the 60s. In his essay, Iván de la Nuez recalls that in some basic documents of political revolutionary history, such as History Will Absolve Me (1954) by Fidel Castro, Cuba and the Road to Socialism (1963) by Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, and Socialism and Man in Cuba (1965) by Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the word utopia does not appear. And yet the concept does, in their description of the Republic of ’40 as good government, or their promise of swift liberation from underdevelopment, or their faith in the advent of the “new man.”

Adiós Utopia questions this exclusive remission of utopianism to the time of the Revolution and the space of the island. Its gamble on a cross-section that challenges territorial partition in Cuban art between here and there, nation and exile, is evident. With a few exceptions, such as “To the Possible Limit” (1996) by José Bedia, which interrogates the insular nature of Cuban culture, nearly all of the works were created on the island and yet, the migration of art and artists is a constant in the show. From Mario Carreño and Rafael Soriano or Carmen Herrera and Antonia Eiriz, to Arturo Cuenca and Tomás Esson or Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas and Alejandro Aguilera, exile is not only a place of residence, but a possible condition of Cuban art.

II

Aside from a utopian notion associated with the autonomy of art under the socialist State, there is another aspect of this exhibition that has eluded the critics who appear in the catalog. The curators did not apply an evolutionary or historicist criteria according to which Cuban art from the revolutionary period would have been utopian at first and then, starting in the 80s, gradually bid farewell to utopia. The viewer is presented first with the abstract and concrete art of the 50s, then the emblematic photos of Raúl Corrales, Alberto Korda and Mario García Joya, but already in the next room, dedicated to Servando Cabrera Moreno, Raúl Martínez and the pop art of the 60’s, we run into the expressionist canvasses “The Procession” (La procesión, 1963) and “The Privileged and the Underdogs” (1963) by Antonia Eiriz, thus confirming that utopia and disenchantment, enthusiasm and critique always went hand in glove with art from the revolutionary period.

This tension becomes more evident as the show advances into the 80s, bypassing the realist or “content-driven” art of the 70s. The dismounting of icons of power propitiated by Cuban visual art starting in the 80s is articulated through masking or superimposition in the works “Science and Ideology” (1988) by Arturo Cuenta, where the metallic shell of a propaganda billboard is shown bearing the image of the Che and the phrase “A revolutionary must work tirelessly,” or “My Tribute to the Che” (1987) by Tomás Esson. The show privileges the interpellation of national symbols or ideologemes of the State in this archeology of farewell to utopia.

But one must ask whether such an interpellation may be defined as a farewell gesture to utopia that extends into the drawings of Fidel Castro by René Francisco y Ponjuán that triggered the shutdown of the Castillo de la Real Fuerza project in 1989, or the hammers and sickles of Flavor Garciandía, or Marx portrayed with the Sacred Heart by Lázaro Saavedra, or Tomás Esson’s flag, and so on all the way up to “Statistics,” from the series Post-War Memory (1995-2000) by Tania Bruguera. While there is ambiguity in the conceptualization of the utopian, here, the distancing feels more imprecise. Farewell to whom? The socialist camp, the leaders, the bureaucracy, the Revolution itself, or the State that created the Revolution?

Tania Bruguera, Estadística (Statistics), 1995–2000, cardboard, human hair, and fabric, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caribbean Art Fund and the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund. © Tania Bruguera

Delving into the 90s, the exhibition questions the notion of a depoliticization of Cuban art following the diaspora of the generation of the 80s in a way similar to what has recently been subscribed to by the critic Mailyn Machado. Sandra Ramos’ work during that decade, especially that which alludes to solitude on the island and the diaspora of hundreds of thousands of Cubans, is a good example of a politicization that appeals to a corporeal image of national fragmentation. In his early work “Constructing Heaven” (1991), Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas proposes an asphyxiating image of an enormous blue wall between earth and sky that transforms the insular utopia into a place of captivity.

It could be even argued, après Boris Groys, that political art in Cuba advances towards a radicalization in the 90s and the first decade of the 21st century that transcends the alternative between “utopia” and “archive” and gambles on not the autonomy of the aesthetic, but rather a “production of sincerity” that is frequently distorted by both markets and institutions, above all in a state-run economy like that of Cuba. From the Art-Street interventions and Juan-Si González we arrive, in two decades, at a confrontational questioning of the apparatus of State Security in the works of Carlos Garaicoa, Tania Bruguera, and Lázaro Saavedra, or a disarming of the very concept of Revolution and the image of the Communist Party, as can be read in works by Ernesto Oroza, José Ángel Toirac, Alejandro González, and Reynier Leyva Novo.

Speech engulfed by power in its construction of discursive hegemony over the course of more than a half-century has been, since the 80s, one of the main targets of visual criticism in Cuba. In “Ball or Discourse” (1989), Tomás Esson painted an endless tongue as a symbol of totalitarian speech. In “Opus” (2005) by José Ángel Toirac, that same tongue repeats statistics over and over again, in the never-ending voice of Fidel Castro. In “Struggle, Resist, Overcome” (1990), Carlos Rodríguez Cárdenas decoded the language of the State through sexual possession of the Other. In “They’ll Still Know How to Defend It” (1990), Alejandro Aguilera projects the topics of Cuban nationalism over a pitiless reality, one that seems to have exhausted its civic energies.

This turn toward a poetics of sincerity becomes evident in the performance “Prodigal Son” (2010) by Carlos Martiel, where the artist pins medals of military glory to his naked chest, or in the video “The Golden Age” (2012) by Javier Castro, in which Cuban children say that when they grow up, they would like to be “foreigners” or “dictators.” It finds its counterbalance in the excess or channeling of irony practiced in the work of the duo Los Carpinteros (Marco Castillo and Dagoberto Rodríguez), but also in that of Alexandre Arrechea and the artists from more recent generations, such as Glenda León, Alejandro Campins, Wilfredo Prieto, and Yoan Capote.

The work “Stress (in memoriam)” (2012) by Capote encapsulates life in Cuba during the first decades of the 21st century within the image of a mound of stones raised over the teeth of an entire community. As in Bruguera’s flag or early works by Antonia Eiriz, the masses are no longer a uniformly enthusiastic people, but rather a controlled, subjugated citizenry. These somber statistics say something equivalent to the vacuum and dismantled triumphal arch of the Revolution in a provincial town, painted by Alejandro Campins in his canvas “Born January 1, 1959” (2013).

In its most sophisticated form, the farewell to utopia means the opposite of the legendary photo taken by José Figueroa, “Olga” (1967), in which one who stays behind bids farewell to one who leaves. That other farewell is subtly exposed in the video by Alexandre Arrechea, where the idea of the Revolution as a heavy file or blank text resting on the arms of the artist, concealing his face, suggests the domestication of utopia by history. While Arrechea’s video is entitled “The Weight of Emptiness” (2005), the work by Reynier Leyva Novo, “Nine Laws” (2014) forming part of a series entitled “The Weight of History,” revisits some of the fundamental judicial provisions of the history of the Revolution from the early nationalizations in 1960 to the most recent “Law of Foreign Investment” of 2014, decreed by the regime of Raúl Castro.

The farewell to utopia in Novo or in the works on paper parting from the Cuban Constitution by Fernando Rodríguez are artistic gestures that prove just how invested utopia is in history. A superficial reading of this poetic intervention would be that upon visualizing the abandonment of utopia in the project of a State built by the Revolution, nearly six decades later, the artist argues a return to the legal foundations that originated Cuban socialism. Another reading, more in touch with the meaning of the show in Houston, is that the farewell to utopia was always there, in the institutional and judicial reproduction of the new social order, and that the advance towards capitalism in 2014 responds to the same logic of power that negotiated the insertion of the island into the soviet bloc in 1960.

Los Carpinteros, Faro tumbado (Felled Lighthouse), 2006, mixed media, American Fund for the Tate Gallery, courtesy of the Latin American Acquisitions Committee 2006. © Los Carpinteros / photo courtesy of the artists

The “Felled Lighthouse” (2006) and “Irreversible Conga” (2012) by Los Carpinteros, found in the final room of the exhibition, synthesize this long process of construction and deconstruction of utopia. Here we find a perfect metaphorization of the chronological paradoxes that characterize the Cuban Revolution and the socialist State it edified and that, despite all the hardships, survives today. But this is not an empty or immaterial metaphorization in which the subject of history vanishes. The lighthouse has not “fallen” of its own accord, it has been “felled” and the “irreversible” conga, which marches backwards, is played and danced by the community itself. There are no “absent subjects” or “people without attributes” to be found here like the ones that, parting from a serene critique of Michel Foucault, Wendy Brown identified as part of the neoliberal aesthetic.

Perhaps the discursive gap between curatorship and critique, or between utopia and farewell, that can be seen in this show by CIFO and the Museum of Houston has to do with the fact that the relationship of Cuban visual art and utopian representations has been hegemonically conceived of not as the refutation of the myth of an ideal society, but by apologists. In order to balance the scales one would have to read Daniel Bell, Russell Jacoby, and Francois Furet along with Bloch, Buber, and Mannheim, to say the least. With a more complete panorama of knowledge on the subject of utopia, we may come to understand why Louis Auguste Blanqui, the founding father of the 20th-century left wing movements, recommended that revolutionaries “stay clear of the path of utopia and stick close to politics.”

Rafael Rojas is a Cuban historian and literary critic. He has authored more than 10 books. His Twitter is @ibrocrepusculo

Rafael Rojas is a Cuban historian and literary critic. He has authored more than 10 books. His Twitter is @ibrocrepusculo

©Literal Magazine

Notes

- Rachel Weiss, To and From Utopia in the New Cuban Art, Minneapolis, The University of Minnesota Press, 2011, pp. 8-13 and 240-247.

-

Alejo Carpentier, Ensayos, Havana, Editorial Letras Cubanas, 1984, pp. 300-303.

-

Luis Camnitzer, New Art of Cuba. Revised Edition, Austin, The University of Texas Press, 2003, pp. 8-19.

-

The history of censorship in Cuba, specifically in the visual arts, from the 80s onward has not yet been written. See, for example, how censorship becomes taboo in anthologies of art criticism from the 80s, such as Déjame que te cuente (Let Me Tell You, Havana, Consejo Nacional de las Artes Plásticas, 2002), by Margarita González, Tania Parson, and José Veigas. In the prologue to said anthology, Elvia Rosa Castro refers thus to the censorship of Volume One at Galería L “in 1978” (in fact, it took place in 1980): “after the show that was never inaugurated at Galería L and in the end, was exhibited at the home of José Manuel Fors, things would never be the same,” p. 10.

-

Elsa Vega, “The 50s and 60s in Cuban Art: Two Decades of Essences and Revolutions,” Adiós Utopia. Art in Cuba Since 1950, Miami, CIFO, 2017, pp. 73-81; Gerardo Mosquera, “Art and Utopia. 1970 to 1990: Two Decades in War,” Adiós Utopia. Art in Cuba Since 1950, Miami, CIFO, 2017, pp. 91-100.

-

Abigail McEwen, Revolutionary Horizons. Art and Polemics in 1950s Cuba, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2016, pp. 201-214.

-

Antonio Eligio Tonel, “Epiphany, Drum and Coca Cola: The Present and the Past of the Utopic in Cuban Art,” Adiós Utopia. Art in Cuba Since 1950, Miami, CIFO, 2017, pp. 28-30

-

Martin Buber, Caminos de utopía, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2006, pp. 18-20.

-

Karl Mannheim, Ideología y utopía, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004, pp. 230-239.

-

Iván de la Nuez, “Tomorrow Was Another Day”, Adiós Utopia. Art in Cuba Since 1950, Miami, CIFO, 2017, pp. 61-69

-

Mailyn Machado, Fuera de revoluciones. Dos décadas de arte en Cuba, Leiden, Almenara, 2016, pp. 15-41.

-

Boris Groys, Volverse público. Las transformaciones del arte en el ágora contemporánea, Buenos Aires, Caja Negra, 2016, pp. 37-47 and 133-148.

-

Antonio José Ponte, Villa Marista en plata. Arte, política, nuevas tecnologías, Madrid, Colibrí, 2010, pp. 231-236.

-

Wendy Brown, El pueblo sin atributos. La secreta revolución del neoliberalismo, New York, Malpaso, 2016, pp. 93-101.

Posted: May 16, 2017 at 9:47 pm