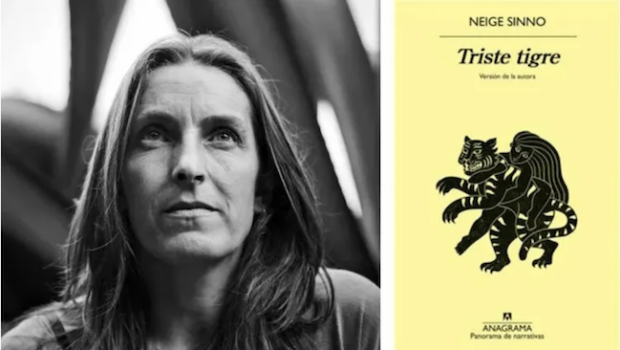

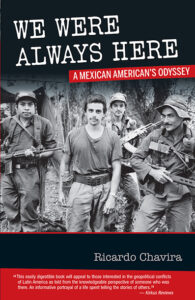

We Were Always Here

Ricardo Chavira

CHAPTER ONE

Running with the Rebels

Desperately, the heavily armed guerrillas and I scaled a steep, verdant hill in northern Nicaragua. In withering afternoon heat, the very fatigued twenty-seven rebels, my colleague and I pressed on at a grueling pace, often slipping and stumbling on loose soil. For the last hour, the muffled boom of Nicaraguan military artillery told the fighters their enemies were close. Vastly outnumbered, the guerrillas had to keep moving.

The group’s mustachioed 29-year-old commander, Alfa, looked over his shoulder, his face tightened in fear and anger. “They are bombing where we just were. If we don’t hurry and get out of here, they’ll be on top of us.”

Alfa and his young, American-trained and -armed Nicaraguan peasants were Contras, that is contrarevolucionarios, or counterrevolutionaries. They were locked in a three-year-old war with the leftist Sandinista government. The group included two women combatants, photographer Bob Nickelsburg and me. Both Bob and I were on assignment for Time magazine.

Weeks earlier, Alfa and his fellow combatants had engaged in a raid from their Honduran base into Nicaragua’s Nueva Segovia Department, blowing up electrical power lines, mining roads, fighting Sandinista troops and murdering two civilian government collaborators. Now, on Good Friday, 1984, the Contras were again in Nueva Segovia being chased by insurgents with murderous intent. The rules of this war dictated that captured fighters were immediately often executed.

I was terrified yet focused on returning to the safety of the Honduran border, some twenty miles to the north. Strangely, I was struck by the improbability of my dire situation. I thought of the great physical, intellectual and emotional distance I had traveled to be at this torrid, dangerous spot in Nicaragua. To this day, I don’t understand why such thoughts came to me. My journey had begun some twenty-five years earlier as a poor Mexican boy in Southern California.

That journey would imbue me with a strong sense of dual identities, one Mexican, the other American. This biculturalism would enable me to navigate and understand the very different worlds and cultures of Mexico and the United States. As a journalist, I would view and interpret the world from the perspective of the poor, and my long immersion in Mexican culture allowed me to perceive Latin America as few Americans could.

When I was in Latin America, my Latino appearance allowed me to blend in. Then, as now, American journalists were overwhelmingly Euro-Americans, or we can say, simply middle-class white people, who grew up with the privileges afforded to those who lived in mainstream America. They could not see the world as I did. I found this was true even of white reporters who spoke fluent Spanish.

My experience would be filled with journalistic adventures in dozens of nations, including the Soviet Union, Vietnam and much of the Middle East. I would enjoy a first-hand view of historic events.

That years-long voyage would demand that I overcome the obstacles of poverty, racism and a dysfunctional family. I had struggled through high school, rejected gang affiliation, avoided committing serious crimes, evaded the Vietnam war draft and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees. In my early twenties, I sometimes let myself dream of becoming a foreign correspondent for a top-tier American periodical. But I could not truly believe I would realize that dream.

Mine was an uncommon odyssey, since most Mexicans in the United States of my generation typically did not attend college. Sometimes I felt my goal of becoming a professional journalist was unrealistic. I was discouraged because there were only a handful of Latinos in mainstream English-language journalism. Institutional racism was an imposing barrier for those of us who were not white men. Even after I made my way into a newsroom, I fought to keep from being pigeon-holed as a “Hispanic” reporter. I was a journalist who happened to be Mexican—a mestizo comprised of European, indigenous Mexican and African ancestry—fully capable of reporting any story, including those that benefited from my Latino perspective and intimate knowledge of my American homeland.

I eventually earned the respect and trust of my colleagues and bosses at several news organizations and took on stories ranging from Los Angeles city hall to Mexico’s Palacio Nacional, the US-Mexico border, Central American wars, historic summits and American diplomatic affairs in Washington, DC. As I reported and edited stories of every sort, traveling to more than forty nations, I would earn awards, including the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for international reporting.

I found that my profound identification with my Mexican heritage and the poor set me apart from most American journalists of my time, who I saw as privileged white people. Of course, I could not know that my Nicaraguan predicament would provide a dramatic chapter in my growth as a journalist. Nor could I imagine Central America and its poor would remain a US foreign policy concern well into the 2000s. I would witness how Washington’s support for repressive regimes would set in motion the current mass exodus of Central Americans to the US-Mexico border.

ab

Our Good Friday escape began festively. At dawn, we arrived at a small hilltop farm. The family who lived there told us they were preparing to commemorate Good Friday, and so they generously shared with us coffee, sweet biscuits and fatty duck soup. The family knew several of the adolescent fighters who were from the area. As pop music from the local Sandinista radio station blared, a party was in the making. Then at about 8 am, Alfa used his binoculars to scan a valley from our perch. He muttered, “piricuacos,” a disparaging term for the Sandinistas that meant “rabid dogs.” I borrowed the binoculars and saw East German IFA trucks disgorging hundreds of troops. The Sandinistas were launching a sweep. Quickly, the fiesta ended as the Contras grimly hoisted US Army-issue backpacks, Belgian FAL assault rifles and Soviet AK-47s. There was an oppressive sense of urgency and apprehension as we set off.

Alfa decided we should move along a route toward the Honduran border that arced beyond the Sandinistas’ flank. Alfa’s outnumbered fighters had to avoid detection. We would march as much as possible where vegetation afforded us coverage. The next fifteen hours were an exhausting and frightening ordeal. We stumbled along the rocky creek beds, often clawing our way in darkness through dense vegetation. Mindful of the Sandinistas scouring the area, we hustled

relentlessly.

By mid-afternoon, a Sandinista patrol was not far behind. Pelón, whose dark indigenous features and gold-capped teeth made him look fierce, greeted the news enthusiastically. He raised his rifle and shouted, “Piricuacos, sons of whores! We’re ready!”

Just then, two Contra scouts who trailed behind to detect Sandinistas in pursuit confirmed by radio that the force was much larger than Alfa’s. A battle, Alfa reasoned, would be too risky. Scouts in advance of the group radioed that there was no sign of government troops ahead.

Alfa was more convinced than ever that we should dash for the safety of the Honduran border, still many hours ahead.

Pelón was disgusted. “We could ambush them, then slip out of here,” he told Alfa.

“No,” Alfa replied, “now’s not the time to fight.”

Just as he said that, we could hear distant artillery fire behind us. I, for my part, was nearing the limits of my endurance. Almost from the start of our foray into Nicaragua six days earlier, my feet had become blistered; the blisters quickly turned into deep lacerations on my heels that burned with intense pain. Compounding my misery was the pace of the hours-long trek with no more than a periodic few-minutes rest. Throughout the trip we had to traverse steep hills, through patches of dense brush, while subsisting on little food. A few mouthfuls of red beans and a couple of tortillas were all we ate most days. One day we had only a hardened cone of brown sugar to deaden our hunger. The combined effect of having my feet painfully injured, nearly a week of arduous marching, scant food and now the frantic pace left me near collapse.

Gasping, I sank to one knee. I told Roberto, an adolescent Contra who always walked beside me, attentive to my well-being, “I’ll stay here. You guys go on without me. When the Sandinistas get here, I’ll explain that I’m a journalist and ask them to take me to Managua.”

I was certain I couldn’t walk any further. It was time to extricate myself from this awful misadventure. I was stupid to have undertaken the assignment, I thought. Nickelsburg was several yards ahead of me and unaware of my decision. Roberto pointed out that I was wearing American army fatigues—clothes I thought would make me less conspicuous—and the Sandinistas might not believe I was not a Contra or in some way collaborating with them.

“They will probably kill you,” he said.

And so, I rose and pressed on, energized by the realization that I was no longer a neutral participant, but the quarry in a brutal war.

We marched all night, feeling our way sometimes. I slowed the group with my frequent need to pause to gather strength. At about midnight, Alfa said it was safe to rest because we were far ahead of the Sandinistas. We collapsed on a hilltop. I fell asleep as soon as I hit the ground.

An hour later, we were on the march again. We came to the unpaved road called the Ocotal Highway, the region’s main thoroughfare. Crossing it dangerously exposed us, so we ran across. The road, I learned, had become the de facto Honduras-Nicaragua border, and it was also the site of many Sandinista ambushes. The Contras had a heavy and permanent presence beyond the road.

By noon we were back at the Contras’ Camp Nicarao, just inside Honduras. Comandante Mack welcomed us. A former Nicaraguan National Guard Sargeant whose real name was Benito Centeno, he oversaw operations in Nueva Segovia. Centeno was eager to hear about the trip. He was just as eager to argue that without American aid, their war would go nowhere. Congress was debating whether to continue aiding what had become a controversial war to topple a government.

“Legislators might think that helping us will cost them votes,” said Centeno, stocky, dark-skinned and clad in pressed fatigues. “They should also look ahead five or six years. If we are not around by then, the United States will have to send Marines into Nicaragua. This is not something we would like to see. With American help, we Nicaraguans can save our

nation.”

Next, Centeno offered me and Nickelsburg what seemed like a banquet: canned tuna with scrambled eggs, tortillas and a Coca-Cola. I had lost nearly twenty pounds during the foray, and I ached all over. By late afternoon, Nickelsburg and I were in Tegucigalpa, where I would write my story for Time and reflect on my trip.

A month earlier, I had pitched my idea to Edgar Chamorro, a top official of the Honduras-based Contras, known as the Nicaraguan Democratic Force, or FDN. A few weeks later, he phoned me in Mexico City, cryptically suggesting I visit Tegucigalpa. Once in the Honduran capital, trip details were worked out. Nickelsburg and I went to a Contra house a few blocks from the US embassy on the morning of Friday, April 17, 1984. Soon we were on our way aboard an SUV to a Contra base camp sixty miles southeast of the capital. As we tore down a stretch of road, Honduran peasants glared at us. Youths bathing in a river shouted insults as we passed. Honduran soldiers had made large stretches of the border with Nicaragua off-limits to ensure the Contras’ security. This arrangement bred peasant resentment at what was viewed as an occupying force.

Before noon we were at Camp Nicarao, named for a sixteenth-century indigenous chief famous for his wisdom and courage. The camp, just two miles from Nicaragua, was a cluster of olive-green US Army tents. A few hundred Contras were in the camp. A clinic, a mess hall, an armory and several tent warehouses covered a few acres. Mule trains left there for Nicaragua carrying weapons, ammunition, mines and other supplies. I saw a man who appeared to be an American or European in one of the tents operating a lathe. He ducked when he spotted me. Most likely he was a CIA agent or operative. I also discovered several dozen landmines stored next to a large earthen wall. The Contras had denied ever planting the devices.

The base commander, Alfredo Peña, who looked more like an accountant than a warrior, greeted us. In briefing us on our trip, he predicted that the Contras would be the first insurgency to overthrow a communist government.

Some five hours after our arrival, we heard exploding mortar rounds. As the steady thuds grew louder, Peña revealed that the Contras and Sandinistas were battling a few miles over the border. Some fifty Contras headed out to the fight; an hour or so later, about a dozen adolescents arrived. They lined up and a Contra gave them tips on how to shoulder their weapons and fire: “Make sure you keep several paces apart when you are marching, and when the shit starts, hit the ground. And then don’t be afraid to fire back.”

We expected to leave for Nicaragua at dawn the next day, but the fighting had only just ended, and conditions were still unsafe. No one would disclose to me the battle’s outcome. At around noon, we set out. A sinewy gray-haired mulatto named Armando and five armed adolescent Contras were to guide Bob and me into Nicaragua. Within the first few hours, I began to regret making the trip. Much of the walking was up 45-degree mountain trails, with the temperature exceeding 90 degrees. Late that afternoon we arrived at a Contra hilltop outpost in Nicaragua’s Nueva Segovia Department. Several contras, including two women, welcomed us. I was drenched in sweat, bone-tired, my heels lacerated by the stiff, new boots I wore. We were asleep by nightfall.

Over the next several days, we would march deeper into Nicaragua—some twenty-five miles in all—as a test of Contra military prowess and civilian support. Alfa told us he had orders to only engage in combat if attacked, this to help ensure Nickelsburg’s and my safety.

In the dim light of dawn of our second day, we approached the Ocotal Highway. We crouched and scurried across. A few hundred yards further on, one of the Contras shouted for us to halt. He had spotted a landmine firing mechanism, a small metal cylinder less than an inch above the ground. In all, Contras and Sandinistas would plant 180,000 mines, mostly in northern Nicaragua.

Later that day, we arrived at a farm where the residents happily greeted the group. “We are Contras,” said “the grandmother,” the code name for an elderly supporter. Smiling and clasping one of the young Contra’s arm, she added: “These are our people. They are from here. We are in the same struggle. They fight with arms, and we support them with food and shelter.”

We marched on in the early afternoon along a dry creek bed. Suddenly a peasant leading a mule hurried toward us. Alfa tensed and ordered the man to halt. The man was talking excitedly. Alfa said the peasant warned that a large Sandinista patrol was headed in our direction. We hid in the brush that lined the creek bed. About thirty minutes later, on a path about fifteen feet above us, we heard boots tromping on rocky soil and loud chatter. I scarcely dared breathe. It was a surreal few minutes. I thought our predicament was very much like one torn from a war movie.

When the apparently large patrol moved on, we quietly resumed our own march. We trudged on for the next few days, stopping at farms for rest and provisions. Unfortunately, the farmers had little food. Bob was holding up better than I was. My feet were a mass of bloody sores that soaked my socks, and I was constantly tired. All the peasants I interviewed told of being oppressed by the Sandinistas, thus driving them to back the Contras.

At one farm, the Contras gathered twenty or so peasants for a town-hall-style meeting. The men were clad in tattered clothes and rubber boots.

“I took my son—he is thirteen—to one of the piricuaco schools so he could learn to read and write,” said one of the men. “They put a uniform on him and had him carrying a rifle. They brag about their literacy campaign but say nothing about making the boys soldiers.”

Others said state security agents persecuted them. A farmer named Don Víctor said agents had threatened him days earlier. “They know the Contras could not exist here without our support, so we are threatened. One of the men who came to my farm said, ‘We know you sons of whores are with the Contras. One of these days we are going to murder you and be done with the problem.’”

The Contra movement began in 1979 when former national guardsmen launched an armed anti-Sandinista insurgency. Initially, almost all Contras were linked to the deposed regime. Eventually, disillusioned Sandinistas joined their ranks, as did many peasants. Some were fighting because a relative had joined the FDN while others were drawn by the $100 they were paid monthly. Others said they were fighting solely out of the heartfelt conviction that Nicaragua would be better without the Sandinistas in control, although they did not know what sort of government should replace the one in power.

Years earlier, Alfa had worked as a radio repairman in his native Nueva Segovia. He told me that he lived peacefully—even during the revolution that overthrew the dictator, American ally Anastasio Somoza. But in the revolutionary fervor following their triumph, the Sandinistas rounded up suspected Somoza supporters. Alfa said that his three brothers were executed on the false charge of being counterrevolutionaries.

“That made me see we couldn’t have that kind of government,” he said.

Roberto was eighteen, short, with sharp, indigenous features. Several months later he and Alfa would be killed in combat. The adolescent guerrilla told me he had been with the FDN for a year and been in countless battles. Roberto had become a Contra after Sandinista security agents arrested and imprisoned his brother for denouncing the government. He told me about Manuelito, a spirit said to inhabit an abandoned farm. “If you have enough faith, he will speak to you,” said Roberto. “He tells us where the piricuacos have ambushes.”

Late on the afternoon of our sixth day in Nueva Segovia, Alfa announced a change in plans. We were to have linked up with more than a hundred Contras to the south, but now an even larger Sandinista force had moved between us. With the Sandinistas near, we maintained silence. Before dawn the next day, Good Friday, we began a trek that hours later would become our headlong dash to escape the Sandinistas in hot pursuit.

My trip demonstrated that while many peasants supported the FDN cause, organized support was spotty and often came without food and intelligence on Sandinista movements. I would learn in a future trip with leftist guerrillas in El Salvador that solid civilian support required a ready supply of food, information and even armed combat, much in the way the Viet Cong aided the North Vietnamese regulars.

During the Ronald Reagan Administration, wars in Guatemala and El Salvador and with the Sandinista government were top foreign-policy issues. They were key to the Reagan Doctrine of “rolling back” global communism. He described it on February 6, 1985: “We must not break faith with those who are risking their lives—on every continent from Afghanistan to Nicaragua—to defy Soviet-supported aggression and secure rights which have been ours from birth.”

Reagan was determined to topple Nicaragua’s government. “The consensus throughout the hemisphere,” he said in a July 18, 1983 speech, “is that while the Sandinistas promised their people freedom, all they’ve done is replace the former dictatorship with their own: a dictatorship of counterfeit revolutionaries who wear fatigues and drive around in Mercedes sedans and Soviet tanks and whose current promise is to spread their brand of ‘revolution’ throughout Central America.”

It was true that Central American revolutionaries received some Soviet, Eastern Bloc and Cuban support. But the Sandinistas were not hardened communists. They adhered to mild socialism. Critics alleged that the Contras were nothing more than terrorists and that the United States immorally had sided with murderous regimes in El Salvador and Guatemala.

At the 1986 White House Correspondents’ Dinner, an annual gala that brings together journalists with the powerful and famous, I sat next to CIA Director William Casey. Someone must have told him about my Contra trip, because in the course of a chat with me, he asked what I thought of the rebels.

“They are not a true insurgency,” I replied. “From what I saw, they do not have broad popular support.”

Casey nodded and said, “That’s what I thought.”

The Reagan Doctrine would lead to the Iran-Contra Scandal. White House officials, among them National Security Council staffer Oliver North, illegally procured funds to arm the Contras. The efforts included the secret sale of TOW missiles to Iran during that nation’s war with Iraq.

The Contras were a Reagan Administration creation. They would not have existed without US support. All fighters drew monthly pay, and CIA agents armed and trained them. Some of the leadership had been soldiers during the Somoza years. The Contras operated almost exclusively from bases in Honduras. That country, in exchange for allowing the Contras to operate unmolested, received substantial American aid.

After covering the war against Nicaragua by talking to Contra and American officials in Tegucigalpa, I had to have a first-hand look at this conflict that was being fought in remote areas of Nicaragua. There was no other way to accurately judge the truth of claims that the Contras were quickly developing as a potent military and political threat to the Sandinista government. But the theater of combat was not only remote but shrouded in CIA-imposed secrecy.

Traditionally a backwater, Tegucigalpa had with the war on Nicaragua become thick with intrigue. The CIA was in town to run the war, and middle-aged American men wearing cowboy shirts were everywhere. They hung out together at the Honduras Maya Hotel, speaking in hushed tones. Who were they? Other journalists and I guessed they were CIA agents or operatives. I would learn that Tegucigalpa had also attracted mercenaries and arms dealers.

The American embassy added heightened intrigue and mystery. American diplomats hinted that the war was to a large extent being run out of the mission, with Ambassador John D. Negroponte at the helm. Negroponte was a staunch Cold War warrior who had rendered diplomatic service in Vietnam. Officially, the United States was not running the Contras or the war. The implausible line was that the Contras were an indigenous force that Honduras decided to support. In fact, US military aid to Honduras jumped from $4 million to $200 million between 1980 and 1985. The aid was payment for Honduran collaboration and hosting of the Contras, who relished the intrigue. They met journalists only at places they deemed secure, supposedly to avoid Sandinista agents known to operate in Tegucigalpa. All in all, it made for a banana republic Casablanca.

The Contras, who demobilized in 1990 after the Sandi-

nistas lost a presidential election, focused on soft targets, such as farms, clinics and civilians. A 1989 Human Rights Watch report called them “. . . major and systematic violators of the most basic standards of the laws of armed conflict, including by launching indiscriminate attacks on civilians, selectively murdering non-combatants. . . .” The Sandinista revolution and the Contra war together killed some 30,000 combatants and civilians.

A former Sandinista supporter, Edgar Chamorro concluded that the revolutionaries were anti-democratic. He was appointed as an FDN director and the group’s press attaché. Chamorro would lose a power struggle, leave the FDN and become a vocal Contra critic. In a 1987 interview, he said that the CIA dictated what he should say publicly.

“I was told to speak about bringing democracy to Nicaragua, but we all knew that our purpose was to overthrow the Nicaraguan government,” said Chamorro. “The CIA gave us a list of things to say about the Sandinistas to make them look like communists. And we were told to deny working with the CIA, that all our funding came from private sources.”

The Contras would for years be a Reagan Administration foreign policy obsession, one that demanded media coverage. So, in early November 1986, I briefly left my Washington bureau duties and traveled to the Honduran-Nicaraguan border. Time editors reasoned that my recent on-the-ground reporting in Honduras would give me enhanced insight into the Contra war. Indeed, no one in the Washington bureau had ever been to Central America.

My reporting at the State Department and Capitol Hill suggested that the Contras were weaker militarily than they had been two years earlier, when I had traveled with them. This was significant because starting in October 1986, US military aid had, after a two-year prohibition, begun to flow once more. In addition, the Contra ranks had increased from 8,000 fighters in 1984 to 11,000 in 1986.

Immediately after arriving in Honduras, I headed for “The Road of Death.” The dirt highway and surrounding area close to the Nicaraguan border had experienced a surge in combat. Significantly, Sandinista troops had crossed into Honduras to fight the Contras and, whenever possible, disrupt their logistical structure.

Despite its ominous appellation, the dirt road in southern Honduras’ El Paraíso Department cut through pine-covered mountains and offered scenic views of grassy meadows, a majestic valley and flocks of tropical birds. In places, the road ran only yards from Nicaraguan territory. El Paraíso Department was where most of the Contras had several bases. The bases were used for training and as staging grounds for incursions into Nicaragua.

The road had earned its nickname following the 1983 deaths of American journalists Dial Torgeson and Richard Cross. They were killed when their car hit a landmine that Sandinista troops had planted to disrupt Contra supply lines. I saw the burned-out hulk of a truck that was used to ferry supplies to the Contras at a base called El Paraíso. A month earlier, Sandinista soldiers had slipped across the border and fired an RPG round into the supply-filled vehicle.

A string of Honduran army bunkers manned by young soldiers was spread along the road. Their M-16 rifles jutted over the edge of the protective shelters. Several hundred yards to the south of the border, Sandinista soldiers looked back from behind their own sandbags. “Sometimes they greet us,” quipped a Honduran private, making light of the gunfire that erupted from the other side.

The day I was there, just a few hours later, there was a 45-minute firefight. While no one was killed or injured, the road and the surrounding Honduran territory were being dragged into the Contra-Sandinista war.

Two years earlier, the Contras had for the most part been taking the war to the Sandinistas. Now, Sandinista troops had taken up fixed positions in Honduras. Hundreds of Contras had clashed repeatedly with the invaders but failed to dislodge them.

This was an ominous development for the Contras and Honduras alike. Already the consequences were apparent, and nowhere was this clearer than in Las Trojes, a bustling farming town of some 40,000 right against the border with Nicaragua. The intermittent fighting in the surrounding countryside had driven about 2,000 farmers off their land and into Las Trojes.

“Before we lived in tranquility,” said Jacoba Torres, a sixty-year-old farmer with a deeply wrinkled and weathered brown face. “Now, we hear bombs and gunfire all the time. We know that the Sandinistas are all around us. They have put mines in the ground, and many people have stepped on them.”

She and her husband had fled from their farm. “We were not the only ones,” Torres said. “There was too much fear. The Sandinistas took a whole family away; nobody knows why. People thought they would kidnap all of us, so now the area is abandoned.”

American and Contra officials said the Sandinista strategy was to choke off shipments to the Contras in Nicaragua. Las Trojes was an important resupply point, where the Contras would be back on their heels.

Adolfo Calero, head of the FDN and the most powerful of the Contras, told me that American military aid had arrived slowly. After Congress learned of the CIA’s role in mining Nicaraguan ports, it ended Contra funding. Reagan on October 16, 1986, signed into law some $70 million in military aid and $30 million in humanitarian aid. In what would prove to be the tip of the Iran-Contra scandal, there was clear evidence that a clandestine network was arming the Contras. The network, it would be revealed, was, in fact, an illegal, American operation that had been delivering arms to the Contras even when US law prohibited it. Between 1984 and 1986 the NSC staff had raised $34 million for aid to the Contras from third parties, such as Saudi Arabia and Brunei; millions more were raised from donors at conservative fundraisers. Oliver North spearheaded the covert funding, depositing funds in Swiss bank accounts. North and Contra leaders had access to the funds.

While I was based in the region from January 1984 to January 1986, fellow journalists and I heard persistent rumors of an off-the-books Contra supply operation based at El Salvador’s Ilopango airfield. But the facility was closed to journalists, and sources denied the rumors.

A downing of a C-123 supply plane over Nicaragua on October 5, 1986 was noteworthy because the crash’s lone survivor told his Sandinista captors that he was working for the CIA. Eugene Hasenfus was sentenced to thirty years but then pardoned and released. I interviewed Elliot Abrams, Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Inter-American Affairs, soon after the incident. He assured me repeatedly that Hasenfus was not working for or in any way connected to the American government. Abrams stated he was simply unaware of any such relationship, that he knew of all activity and so he could authoritatively assure me that Hasenfus was not connected to the Reagan Administration. It was just one of many lies Abrams would tell when the scandal broke.

The Hasenfus incident helped uncover the Iran-Contra crimes. Hasenfus’s capture brought to light the fact that during a period when lethal aid to the Contras was banned, the National Security Council, with North in the lead, kept the arms and equipment flowing. The official line was that the Contras had been left to fend for themselves.

The black resupply operation, according to FDN official Indalecio Rodríguez, was poorly managed. “We didn’t know how to get the supplies to where our troops were,” he said. In Nicaragua’s north-central Matagalpa Department, Rodríguez claimed, “We had 500 of our armed men who had to protect 1,500 who had no arms. We had no way to deliver them. Another time, we bought a lot of jungle boots, but they were poorly made. In a week, we had our people barefooted.”

Abrams blamed Washington’s aid cut-off for the Contras’ loss of territory. Echoing Rodríguez, he claimed the lack of expert American administration made for the poor distribution of this purportedly private funding. Of course, Iran-Contra would reveal that there was never a time when the CIA and other Reagan officials had removed themselves from the supply efforts. In truth, the Contras had been put on the defensive because the Sandinistas had benefited from improved counterinsurgency training and ample Cuban and Soviet supplies, including the feared Hind combat helicopters.

Two years earlier, Contra and American officials insisted that the rebels were a force to be reckoned with. Now, the line was that the Contras had to make a comeback and then push on to final victory. The words lacked conviction.

Several weeks after my visit to Las Trojes, the Iran-Contra affair burst into the public arena, marking the beginning of the end of American efforts to overthrow the Nicaraguan government. The war would end without so much as a whimper.

Certainly, of all the reporting assignments I had held, none excited me as much as covering Central America and Mexico. I already had several years of reporting experience in Mexico and the Mexican-American borderlands for The San Diego Union. But I was hungry for more. At first, I was absorbed by Mexico’s economic turmoil. That proud nation’s painful and distressing decline with its obvious implications for the United States was a major news story. I also felt a strong personal connection with Mexico.

In March 1982, a Tijuana leftist, José Luis Pérez Canchola, told me that hundreds if not thousands of Guatemalan indigenous people had in the last few weeks fled into the jungles of Mexico’s Chiapas state. Pérez explained they were survivors of a Guatemalan army genocidal campaign. At that time, the Central American nation was in its second decade of armed conflict with leftist rebels. Most of the fighting was in the northern Guatemalan provinces of Quiché and Huehuetenango. Leftist rebels had been at war with the government since 1960. The Guerrilla Army of the Poor, or EGP, in 1982 had sizeable support among the nation’s Mayan people.

Pérez said he did not know exactly where refugees were arriving, but he gave me the name of a Catholic priest in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, who likely knew the location. I convinced my editors that photographer Ian Dryden and I would find the refugees. No news organization had reported on what was a little-known refugee crisis.

During the 2,000-mile trip south, I began thinking that my chances of finding the refugees were uncertain. The journey would prove to be one of my greatest journalistic challenges. Failure to confirm the story would have been a major professional blow. But I had faith in my judgment. Pérez was a sober and careful man. I trusted him.

We stopped for a day in Mexico City, where I interviewed an interior ministry official. He claimed there were no refugees. However, he said Guatemalan troops and guerrillas had infiltrated the area, requiring the Mexican government to declare it off-limits. I was forbidden to travel there, he said. While I said I would respect the ban, I decided to go, convinced that the Mexican government was hiding something.

Ian and I arrived in San Cristóbal de las Casas, a city high in the mountains of Chiapas. Inhabited for several hundred years by highland Mayans, the Spanish arrived to build the first church in 1547. I met with the priest who reportedly knew where the refugees were, but it turned out that he was unsure. He believed it was either Motozintla, a town on the Guatemalan border, or a jungle clearing called Puerto Rico on the Usumacinta River. The priest told me that Catholic priests and nuns were deeply concerned about the crisis but had no uncomplicated way to travel away from San Cristóbal.

In Motozintla, I went to a church on the hunch that priests or nuns would have information. An Irish nun who received us confided that the church had taken in wounded Guatemalan rebel fighters. A few were present. We needed to go to Puerto Rico to find the refugees, she said. On a map, of the Usumacinta the nun located what she was sure was Puerto Rico.

Getting there would be difficult. It was most easily accessible by small plane and a river ride of several hours. We left for Las Margaritas, some 350 miles distant, on the eastern side of Chiapas. There we could find bush pilots who would fly us into the thick Lacandon rainforest. After an all-night drive through thick fog on a winding mountain road, we hired a pilot.

Flying over the one-million-acre Lacandon, I was struck by the seemingly endless expanse of lush greenery. After forty-five minutes or so, the pilot advised we would be landing. I couldn’t see a landing strip until we went into a sharp descent. Just a few feet over the jungle cover, we made a bumpy landing on a dirt strip.

We deplaned and confirmed the date for the pilot’s return. Within a few minutes, some ten Mexican soldiers approached us. The leader told us we could not remain in the area. Ian cleverly offered a pack of cigarettes, which the soldiers eagerly accepted. I explained that we simply wanted to visit the refugees. The soldiers nodded knowingly. They agreed to let us continue but advised us we would need to find someone to take us down the river to Puerto Rico, which lay several hours away.

I saw smoke not far away, and so we headed toward it. There, we found several men engaged in slash and burn cultivation. After exchanging greetings, I asked if anyone they knew could take us to Puerto Rico. A young man named José offered to do so for a reasonable fee, and soon we boarded his dugout canoe. It was about noon as we set off drifting, José using a long pole to push as along. We didn’t see another human for hours.

As dusk approached, José announced that we had arrived in Puerto Rico. A few minutes later, a tall man wearing rubber boots came to the river’s edge to greet us. José knew him, and we introduced ourselves to Emilio. He owned the farm where we found ourselves, and I would soon learn he was the unofficial leader of the farming settlement that stretched several kilometers in every direction.

I explained who we were and why we had come to Puerto Rico. Emilio confirmed that there were about four hundred Guatemalan Mayans living in the jungle nearby. They had begun arriving a few weeks earlier, terrified, thirsty, hungry and often sick. All told of escaping Guatemalan army massacres in Quiché and Huehuetenango departments.

Emilio offered us hammocks, and so, having not slept for some thirty-six hours, Ian and I were soon asleep. Before José left the next morning, we arranged for him to fetch us in a few days.

Ian and I set off to interview the refugees. We came upon the first settlement. Perhaps two hundred Mayans, clad in colorful traditional clothes, had stretched plastic sheeting between poles, forming flimsy shelters. During the next few hours, I would hear stories of unbelievable horror. The Mayans recounted that the military had been combating the EGP, or Guerrilla Army of the Poor, near their villages for years. Most claimed to support the government or said they were neutral. A few said they backed the rebels.

The stories fit a pattern. Without warning, government troops attacked villages, raping women and slaughtering residents with gunfire or machetes. Men and women, old and young, even newly born infants were murdered. Many of the dead were piled together, soaked with gasoline and burned. Out in the jungle, the survivors endured hunger, thirst and disease. During our time there, an infant died of an unknown sickness.

Playa Grande Ixcán, Pueblo Nuevo and Cuarto Pueblo in Quiché Province were some of the villages attacked, residents told me. Several of the villages were part of the Ixil Triangle, an area of southwest Quiché Department. Others were from northern Quiché.

Here, I recount a portion of the story I wrote:

Puerto Rico, Mexico—Felipe Rodríguez squatted in the shade of a ceiba tree, idly poking at an anthill.

Only hours before, he told a visitor, he had returned from his native village, Santa María Tzeja, a two-hour walk along jungle trails in Guatemala. “I had been afraid to go back there,” the tiny, wiry Rodríguez said in a monotone voice. “But I needed to bury my family, so I made myself strong.”

Inexorably, the talk focused on his family’s recent murders. It is the same with many of the hundreds of Guatemalan war refugees in this jungle settlement.

Even a casual conversation with the refugees, Mayans from the northern departments of Quiché and Huehuetenango, elicits talk of a horrifying, unexpected death at the hands of Guatemalan troops. Refugees from places near Mexico, such as La Unión, Santo Tomás, Pueblo Nuevo, Ixtauhacan, Los Ángeles, Mayarán and Kaibil tell of a military campaign started last year and continuing today aimed at wiping them out.

“I guess the government doesn’t want any more Indian race,” said one refugee.

Rodríguez carefully pulled a color photo from a nylon bag. In the photo, he stands smiling, wearing an orange T-shirt, his arms folded across his chest. Children of all ages—his children—and his wife crowd around him.

When the soldiers came to Santa María two months ago, Rodríguez and most of his children were away working on a farm. But the soldiers found his wife and several of the children.

“My wife here, they shot her in the back twice when she tried to run away,” he said, pointing to a plump, dark woman. Two of his daughters, one seven, the other five, wear green dresses in the photo.

“The little one,” he said, pointing to the smaller girl, “they shot her right here,” said Rodríguez, his finger resting just below his left eye. “All of this,” he continued, his right palm cupping the back of his skull, “got blown away. My other little one, they beheaded her.”

Rodríguez and two other men offered to guide us to one of villages that had been attacked. They assured us we would find human remains, proof of the army’s savagery. Ian and I agreed that venturing into Guatemala with killer soldiers on the loose was far too risky. We declined the offer.

Some forty percent of Guatemalans are Mayans, and the other sixty percent are mestizos. As a mestizo, I am more than one-third of indigenous stock. That one-third is comprised of Mayan, Mixe of Oaxaca and Pima of Chihuahua and Arizona. For most of my life, I have felt a bond with native people. It’s literally in my DNA. I felt a powerful connection with the refugees. The horrific nature of the stories overwhelmed me. How could such a widespread genocide continue without the outside world’s knowledge?

The guerrillas could not aid the Mayan Indians; there were too few. There were certainly too few to be a threat to the government, whose massive and brutal campaign was driven by traditional racist prejudice against the Mayas.

Throughout much of the genocide, the US provided military arms and equipment to the Guatemalan government. The CIA worked with Guatemalan intelligence officers, some of whom were on the CIA payroll despite known human rights violations.

Near the end of our first day, Ian and I set about finding a place to stay. We came upon a group of men and women who appeared to be Americans or Europeans. The locals earlier told us some foreigners were in the area collecting butterflies. We greeted them near some huts. They appeared uneasy. When I asked if they had room to spare, one of the men tersely said no. They quickly packed up and set off. I could tell from their accents they were Americans, so their wariness made me suspect they weren’t simple butterfly collectors. Rather, I concluded, they were CIA operatives. I still believe this, given that the CIA and US military were backing the Guatemalan government.

A farmer and his family agreed to rent us space in their earthen-floor hut. They and perhaps another thirty families grew cacao, living without running water or electricity. The nearest road was some 70 miles away. Getting to it would require a grueling trip on foot.

The farmers had formed their own society, complete with rules. For instance, the men told me that a few years earlier they had run off other men who were growing marijuana. They had a hut used to jail wrongdoers. These included men who stole or physically attacked others.

One morning, we awoke to find several Mexican immigration agents interviewing the refugees. The agents said they were not going to deport the Guatemalans but simply wished to compile a census.

On our return trip, we stopped in Mexico City, where I interviewed the Interior Secretariat’s spokesman. To my amazement, he was fully informed of our travels during the past ten days. He would not disclose how he knew, but it was apparent someone had monitored our movements the whole time.

In the coming months, thousands of Guatemalan refugees would find shelter in Chiapas. Camps would be established, and the genocide exposed. Years later, the full extent of the murderous campaign would be made public, but most of the perpetrators would not be punished.

I was haunted by my few days in Chiapas. Back home in San Diego, my mind often returned to the Mayans, the terror they had escaped and the perilous future they faced. I returned a few months later to find thousands more refugees living in still more wretched conditions than before.

ab

In October 1983, Time magazine offered me a job as a correspondent in its Mexico City bureau. At that time, the magazine was at its zenith with a weekly circulation of an estimated four million. It employed fewer than 120 correspondents, so it was a feat to join that elite group. For most of my nine-year career at Time, I was the sole Latino correspondent.

I accepted the job and in January 1984 arrived in Mexico City, where I was assigned to do a story on El Salvador. That tiny nation was engulfed in a civil war. Chiapas had convinced me that significant and terrible events were occurring at our doorstep. I was troubled that, like Guatemala’s Mayas, the people locked in wars, those uprooted, weren’t being heard. Too much reporting ignored them in favor of what Washington officials had to say.

I was increasingly passionate about journalism because it offered me the chance to report about the lives of Latinos, people mainstream American media either studiously ignored or misrepresented. It was important that unheard voices be heard. Also, my bicultural upbringing and deep study of Latino life in the United States and Mexico had prepared me to make a special contribution to mainstream American journalism. I would chronicle the endless, rich and fascinating stories of those who were largely invisible in English-language media. I was convinced that by accurately and fully reporting the untold stories of the poor and powerless, I would enrich the telling of contemporary events.

I loved my work, though it was grueling, sometimes dangerous and required me to be away from my family for long periods. My Latino physical appearance allowed me to blend in with the people in Latin American nations.

*This excerpt from We Were Always Here: A Mexican American’s Odyssey by Ricardo Chavira is reprinted with permission from the publisher (Arte Público Press, 2021).

Posted: July 28, 2021 at 10:25 pm