City of Death, City of Hope

Ciudad de muerte, ciudad de esperanza

Cecilia Balli

Rothko Chapel organized a magnificent series of lectures about violence in Ciudad Juárez. Our special thanks to them for providing us with the permission to cover Cecilia Balli´s work.

* * *

When I was asked to write about Juárez, I found the concept very intriguing. I took my charge literally. I began thinking over the next weeks about what Juárez is, what it stands for, and I also found myself asking what it means to think about the world in terms of specific cities. Because in cities we find all the levels of our existence in one: our material, social, and human realities. A city is not just a grid of streets and highways; it is not just a collection of buildings or a weave of politics and policy. There is something about cities that is intangible, but perhaps more important than anything else–let’s call it the spirit of a city. And this spirit is produced by the individuals who inhabit that city, but it is also much larger than them. Ciudad Juárez, I can comfortably say, has the most special spirit I’ve encountered in Mexico, and this is why, to me, it’s the City of Hope, though the label may sound counter-intuitive.

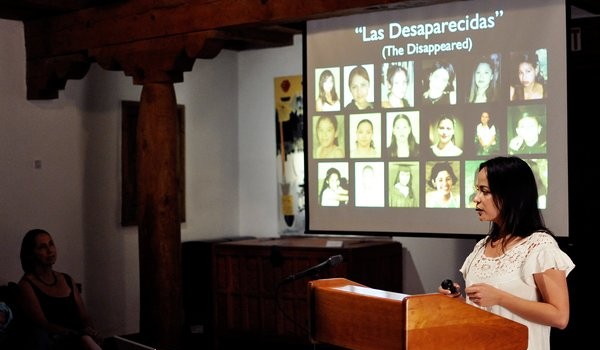

But Juárez is also the City of Death. It’s not a title it has chosen for itself, but one that we impose on it from a distance. My own magazine editors gave this title to the first piece I wrote about Juárez back in 2003–they called it, Ciudad de la Muerte. Because at the time, Juárez had become known as a city where young, pretty women disappeared from the streets mysteriously, and their bodies were later found abandoned in the desert. It was chilling to think of a city where death came in such a dark, unexplained way to the most vulnerable of victims. I have a journal entry created on January 4, 2003, titled “First Arrival in Juárez.” I wrote these words then: “The fear is paralyzing. Especially when you read the paper and realize that they were plucked straight off the streets, in the center of town, in broad daylight. That when they were found, their bodies were horribly mutilated, breasts gnawed or amputated, hair cut off, bodies bitten and slashed.” After spending several weeks in Juárez and then returning the following year for 18 months of dissertation research, I learned that the women’s deaths were much more complicated than that; that not all of the victims fit a profile and not all of the murders were carried out by an organized group of killers. Still, it was clear that the city had produced a new kind of violence against women, more brutal–if not always more numerous–than what other regions of Mexico had witnessed. And it was a style of violence that had also claimed its share of male victims, only they weren’t raped and they were presumed to be men involved somehow in the drug business. Their bodies were buried in backyards in the city or in ranch properties on the outskirts; once, when I was living in the area, the local newspaper reported that a young boy had stumbled upon a hand protruding from the ground. Sometimes, it was discovered that the killers were members of the state police.

But in order to understand how Juárez became the City of Death one has to go much further back than this spate of women’s murders or these hands protruding from the ground. In 1964, the United States terminated the Bracero guest-worker program with Mexico and deported many of its laborers, dumping thousands of men along the Mexican side of the border. In an effort to reemploy them, the Mexican government launched the Border Industrialization Program, which encouraged American manufacturers to assemble their products in northern Mexico in order to take advantage of low taxes and cheap labor. The plan succeeded, but its main beneficiaries ended up being women, who, it was concluded, would make better workers for the new factories, or maquiladoras, because of their supposed manual dexterity. Word spread throughout Mexico that thousands of assembly-line jobs were cropping up in Juárez, and the nation’s north quickly became the emblem of modernity and economic opportunity. In the 1970s, factory-sponsored buses rumbled into the heartland and along Mexico’s coasts and came back with thousands more hungry laborers. Among them were some single women who brought their children in tow. They not only took jobs in the maquilas, but they also began to staff the many stores and restaurants that proliferated to satisfy the city’s newfound consumerism.

And so, if the working women of Juárez had once carried the unfair reputation of being prostitutes or bartenders, they now earned paychecks as factory workers, saleswomen, police officers —a few even managed to get an education and became teachers or managers and engineers in the concrete tilt-ups that were constructed all around town to house around four hundred maquiladoras. For anywhere from $4 to $7 a day, they assembled the automotive parts and electronic components and clothing that we consume. Over time, some of the young women who couldn’t afford to go on to college took computer classes so that they could work as secretaries and administrative assistants. Juárez is a city that places a high premium on skills such as navigating the Internet and speaking English; even in its most impoverished neighborhood, I once saw a tiny brick shack with a dozen chairs planted outside and a hand-painted sign that promised “Clases de inglés.”

But the migration was too fast and too disorganized. The offi cial population shot up to 1.2 million by the year 2000. Gone was the charm that Juárez had claimed in the 1930s, when its valley had produced succulent grapes, or in the ‘40s, when the music of Glenn Miller and Agustín Lara never stopped playing on Juárez Avenue, even as the United States went to war. Men eventually also worked their way into the maquilas, but the cost of living in Juárez had grown much higher than back home, which meant that both parents now had to work and there was no one to care for the children beyond an older sibling – often no more than eight, nine, or ten years old. It was one of Mexico’s biggest blunders to have planted its largest industrial experiment in the desert, in a city separated from the rest of the country not just symbolically, by its distinctly North American feel, but also physically, by the stunning but unforgiving Juárez Mountains. Cardboard shanties began dotting the landscape. Sewage spilled onto the streets in the poorest of places. Electricity was stolen from neighbors and power lines were reproduced like parasites. When I arrived in Juárez seven years ago, it was not uncommon to hear radio talk-show hosts rambling on about the ways in which the immigrants from the south had ruined their community.

Today, the city’s social problems are immense and complex. Even though the American recession has led some factories to close or relocate to Asia, the allure of a maquiladora job remains, and many young people quit studying after middle school and do nothing between the ages of 12 and 15, as they wait to legally qualify for employment. With their parents working, they spend long hours unsupervised, and many young men end up getting into trouble. It is estimated that there are more than 500 neighborhood gangs in Juárez, of which at least 80 are represented in the local prison–where their members serve time for murder, theft, or for selling drugs. Meanwhile in the home, women have joined their husbands as breadwinners but men haven’t necessarily joined their wives as housekeepers or caretakers. There is a high degree of physical and emotional abuse–sometimes resulting in death, which can make the home even more dangerous to women than the street. Mothers in turn pass on their stress to their children; it’s estimated that anywhere from 60 to 70 percent of Juárez women hit their children and are psychologically abusive.

* * *

In 2008, violence in Juárez reached a level never before seen or that any of us had imagined was possible. It began with a killing spree of policemen shortly after the new year started; by mid-February, 26 municipal agents had been gunned down. Shortly thereafter, the killers left a note at a public monument that named the dead and read, “for those who did not believe.” Then, “for those who continue not believing,” followed by a list of seventeen men who were presumably next. Nobody could explain this sudden rash of violence, although the mayor of Juárez, José Reyes Ferriz, would later say that he had gotten word that a rival drug organization had declared war on the powerful Juárez Cartel–though he didn’t explain how exactly he’d found this out. This new group was trying to kill off all those municipal and state police who were on the take of the Juárez group, the theory went.

By then, Mexico was already embroiled in what President Felipe Calderón had declared a “war”. The previous year had been a bloody one for other regions of the country, as drug trafficking alliances and territories shattered and shifted and cartels battled it out with each other. The stakes were raised to an alarming new level, and grotesque flourishes were adopted as a way of sending messages and sowing public terror. Bodies were beheaded and hung from highway overpasses; hands were cut off. In the state of Michoacán, armed commandos slaughtered twelve federal police who had been sent to investigate and left their bodies piled up on a roadside. With time, however, Ciudad Juárez would take the fighting and theater to another level. One victim there was crucified to a tree; the head of another victim was found wearing a Santa Claus hat. People would forget about the women’s murders and Juárez would become known as “the epicenter of Mexican drug violence,” or “the most deadly city in the world.”

Unlike other drug-plagued Mexican cities, Juárez did not have a formal federal government intervention when the killings started, so Mayor Reyes Ferriz and the governor of Chihuahua huddled together to find a response. It was assumed that the police was too dirty to be able to contain the killings, many of which were directed at them. Afraid that the power of the criminals had surpassed their ability to keep Juárez safe, the mayor and governor appealed to President Calderón for help. By March, they received 2,000 troops and ceremoniously launched “Joint Operation Chihuahua,” a multi-government initiative that was expected to serve as a model for the rest of the country. But despite their presence, by the end of 2008, the city’s murder rate had grown five times.

I returned to Juárez in time to witness the last death of the year– victim number 1,651 (to give you an idea of how much worse things have grown since then, so far this year there have been roughly 2,450 murders, or nearly 7,000 in the past three years). But I arrived at the start of 2009 looking for patterns in the seemingly random bloodshed, which the Mexican Army had failed to halt so miserably, even as tanks and Humvees rolled throughout the city. What I witnessed was what the people of Juárez already knew–that the violence there had defied any simple explanation of a cartel war. Males who held no sway in the leadership of the drug trafficking organizations were being slaughtered; men in masks were breaking into drug rehabilitation centers and massacring eight, seventeen, twenty people at once. The vast majority of the city’s victims were poor men between the ages of 18 and 25. Their bodies piled up in the morgue and their killings went uninvestigated. Their deaths spoke of a city in which a turf battle between criminal groups had simply served as the detonator of a much farther-reaching and brutal form of social extermination. Life in Juárez had become cheap./p>

But perhaps the most disturbing thing I learned on that trip was that the Mexican government had some hand in all this. Most people were too terrified to speak about this, but interviews and many conversations held in confidence revealed that the Army was kidnapping young men and disappearing them for days, submitting them to vicious forms of torture in an effort to extract information about the city’s internal drug market. No one was looking for a big capo to bust; this was very low-level information that soldiers sought to acquire after being sent to Juárez with no intelligence of their own to work from. Sometimes the victims were petty criminals, and other times they were picked at random simply because they lived in poor neighborhoods suspected of being dirty. El Diario de Juárez had reported a number of these stories of “human rights abuses,” as they were called, but what struck me was how widespread and systematic they were. These were not a few bad apples acting out of line; it appeared that it became the soldiers’ very strategy, whether sanctioned by their commander or not. Some of the victims died from the beatings or never reappeared, while many others were subsequently sent to the local prison with drugs and weapons charged, presumably to boost the success figures of the operation. And everyone quietly knew this –the Army’s medical examiners, the local and state prosecutors, the public defense attorneys, the staff at the hospitals where some of the victims were taken to prevent them from dying. The doctor at the state prison–who generously treated me for a stomach virus I’d picked up from eating bad fish–told me that all of the detainees who were brought in by the Army came black and blue. And yet nobody would speak up for them, with the exception of a firebrand civil rights attorney named Gustavo De La Rosa and a few of the victims’ families, who held protests in front of the military camp. In March of this year Juárez Mayor Reyes Ferriz visited the University of Texas at Austin campus, and when I asked him why he wouldn’t speak up against the abuses, he insisted that all of the people who were claiming torture at the hands of the Army were, quote, unquote, “hardened criminals.”

* * *

Several years ago, a team of social scientists from Juárez released a comprehensive diagnostic of the city’s complex social reality, offering ideas for intervention. Interestingly, they concluded that while social programs were vastly underfunded, the biggest need in their view was psychological and affective. The people of Juárez have a withering spirit, but at some point they need support. The authors of the study essentially asked, is it enough for a person in this world to have access to a job? Aren’t there other things that matter even more, such as social, cultural, and emotional well-being?

This is why it frustrates me when Juárez today is painted in popular writings as the apocalypse. Because Juárez is not hell on earth, a place where only the bravest of souls step foot–Juárez is a wounded city. Juárez is the example of what happened when people were robbed of their citizenship and forgotten by both the Mexican and U.S. governments. Can we afford to let Juárez explode–or even worse, repeat itself elsewhere? What are the important lessons that Juárez, the City of Death, but also the City of Hope, teaches us about the nature of democracy and global economies and human vulnerability and resilience? Each person has to answer this question for him or herself.

I know that in my case, the city has given me so much more than I have given it. At a recent forum on border violence in Marfa, Texas, writer Charles Bowden was asked by a moderator why he even goes back to Juárez. I thought of how lucky it was that she could even ask that question–and that her panelist could respond. One million people in Juárez–and tens of millions of Mexican citizens–do not have this luxury. But I slept with that question, knowing that the answer went far beyond my sense of journalistic responsibility. And this is what I concluded: The reason I concluded–the reason I go back to Juárez is because the city of death gives me a sense of life.

Traducción de Eugenia Noriega

Cuando me pidieron que escribiera acerca de Juárez, la idea me pareció fascinante. Me tomé el encargo literalmente. En el transcurso de las semanas siguientes empecé a pensar en lo que Juárez es, lo que representa, y terminé preguntándome qué significa pensar el mundo en términos de ciudades específicas. Porque en las ciudades encontramos todos los niveles de nuestra existencia: nuestras realidades materiales, sociales y humanas. Una ciudad es más que una retícula de calles y carreteras; no es sólo una colección de edificios o un tejido de política y políticas. Las ciudades tienen algo que es intangible, pero que quizá sea más importante que cualquier otra cosa–digamos el espíritu de una comunidad. Este espíritu lo producen los individuos que habitan la ciudad, pero a la vez es mucho más grande que ellos. Puedo afirmar tranquilamente que Ciudad Juárez tiene el espíritu más especial que he encontrado en México, y por eso para mí es la Ciudad de la Esperanza, aunque esa etiqueta pueda sonar ilógica.

Pero Juárez también es la Ciudad de la Muerte. No es un título que haya elegido para sí misma, sino uno que le imponemos desde la distancia. Mis propios editores de revista le pusieron este título al primer artículo que escribí sobre Juárez en el 2003–lo llamaron Ciudad de la Muerte. Porque en ese momento Juárez era conocida por las mujeres jóvenes y bonitas que desaparecían misteriosamente en las calles, cuyos cuerpos eran descubiertos después, abandonados en el desierto. Era escalofriante pensar en una ciudad en donde la muerte alcanzaba de una manera tan oscura, tan inexplicada, a las víctimas más vulnerables. Tengo una entrada de diario del 4 de enero de 2003 titulada “Primera llegada a Juárez”. Entonces escribí estas palabras: “El miedo es paralizante. En especial cuando lees el periódico y te das cuenta de que se las llevaron a media calle, en el centro, a plena luz del día. Que cuando las encontraron, sus cuerpos habían sido mutilados de formas horribles, los senos corroídos o amputados, el pelo cortado, los cuerpos mordidos y acuchillados”. Después de pasar varias semanas en Juárez y de volver al año siguiente a quedarme ahí un año y medio para una investigación de tesis, aprendí que las muertes de las mujeres eran algo mucho más complicado; que no todas las víctimas entran en un perfil y no todos los asesinatos fueron perpetuados por un grupo organizado de asesinos. Aún así, estaba claro que la ciudad había gestado una nueva clase de violencia en contra de las mujeres, más brutal–aunque no siempre más numerosa–que lo que se había visto en otras regiones de México. Y era un estilo de violencia que también había cobrado algunas víctimas masculinas, sólo que no habían sido violados y se sospechaba que eran hombres involucrados de algún modo con el narcotráfico. Sus cuerpos se enterraban en los patios traseros de las casas en la ciudad o en ranchos a las afueras. Una vez, cuando yo vivía en el área, el periódico local reportó que un niño pequeño se había tropezado con una mano que sobresalía de la tierra. En algunos casos se descubrió que los asesinos eran miembros de la policía estatal.

Pero para entender cómo Juárez se convirtió en la Ciudad de la Muerte hay que ir mucho más allá de esta oleada de asesinatos de mujeres y manos que sobresalen en la tierra. En 1964, Estados Unidos terminó el programa Bracero de trabajadores invitados con México y deportaron a muchos de sus trabajadores, dejando a miles de hombres abandonados del lado mexicano de la frontera. En un esfuerzo por re-emplearlos, el gobierno mexicano lanzó el Programa de Industrialización de la Frontera, que fomentaba que los fabricantes norteamericanos ensamblaran sus productos en el norte de México con el fin de aprovechar los impuestos bajos y la mano de obra barata. El plan tuvo éxito, pero sus principales beneficiarias terminaron siendo mujeres, quienes, se concluyó, serían mejores trabajadoras para las nuevas fábricas o maquiladoras, por su supuesta destreza manual. Se corrió la voz en todo México de que en Juárez estaban apareciendo miles de trabajos de línea de montaje, y pronto el norte de la nación se convirtió en un emblema de modernidad y oportunidad económica. En los años setenta, camiones patrocinados por las fábricas recorrían el centro y las costas de México y volvían con miles de trabajadores hambrientos. Entre ellos había algunas mujeres solteras que llevaban a sus hijos a cuestas. Ellas no sólo tomaron trabajos en las maquilas, sino que también empezaron a trabajar en las muchas tiendas y restaurantes que proliferaron para satisfacer el nuevo consumismo de la ciudad.

Entonces las mujeres trabajadoras de Juárez, que alguna vez tuvieron una reputación injusta de ser prostitutas o taberneras, ahora obtenían pagos como obreras de fábricas, vendedoras, policías –algunas incluso lograban hacer estudios y se convertían en maestras o gerentes e ingenieras en los edificios de concreto que se construían por toda la ciudad para albergar a cerca de cuatrocientas maquiladoras. Por unos 4 a 7 dólares al día, ensamblaban las partes automotrices, los componentes electrónicos y la ropa que consumimos. Con el tiempo, algunas de las mujeres jóvenes que no podían ir a la universidad tomaban clases de computación para trabajar como secretarias y asistentes administrativas. Juárez es una ciudad que le da un gran valor a habilidades como manejar la Internet y hablar inglés; incluso en su vecindario más pobre, una vez vi una choza de ladrillos muy pequeña con doce sillas colocadas afuera y un letrero pintado a mano que prometía “Clases de inglés”.

Pero la migración fue demasiado rápida y demasiado desorganizada. La población oficial se disparó a 1.2 millones para el año 2000. Desapareció el encanto que Juárez había ostentado en los años treinta, cuando su valle había producido uvas suculentas; o en los cuarenta, cuando la música de Glenn Miller y Agustín Lara nunca dejaba de sonar en la Avenida Juárez, incluso cuando Estados Unidos fue a la guerra. Con el tiempo los hombres también llegaron a las maquilas, pero el costo de vida en Juárez había subido mucho más que en sus hogares, lo cual significaba que ambos padres tenían que trabajar y no había quién cuidara a los niños, más que los hermanos mayores, que con frecuencia no tenían más de ocho, nueve o diez años. México cometió un gran error al haber plantado su experimento industrial más grande en el desierto, en una ciudad separada del resto del país no sólo simbólicamente, por su fuerte sentido norteamericano, sino físicamente, por las impresionantes pero inclementes montañas de Juárez. El paisaje se empezó a salpicar de chozas de cartón. Las aguas negras se desbordaban hacia las calles en los lugares más pobres. Se robaba la electricidad a los vecinos y los cables de luz se reproducían como parásitos. Cuando llegué a Juárez, hace siete años, era bastante común escuchar a locutores de radio divagando sobre las maneras en que los migrantes del sur habían arruinado su comunidad.

Hoy en día, los problemas sociales de la ciudad son enormes y complejos. A pesar de que la recesión norteamericana hizo que algunas de las fábricas cerraran o se reubicaran en Asia, el atractivo del trabajo de maquiladora permanece, y muchos jóvenes renuncian a sus estudios después de la primaria y no hacen nada entre los 12 y los 15 años, mientras esperan a estar legalmente calificados para trabajar. Mientras sus padres trabajan, pasan largas horas sin supervisión, y muchos jóvenes terminan por meterse en problemas. Se estima que existen más de 500 pandillas en Juárez, de las cuales al menos 80 están representadas en la prisión local –donde los miembros cumplen condenas por asesinato, robo o narcotráfico. Mientras tanto, en casa, las mujeres se han unido a sus esposos en el sostén económico de la familia, pero los hombres no necesariamente ayudan a sus mujeres con las tareas del hogar y la crianza. Hay un alto grado de abuso emocional y físico, que en ocasiones incluso resulta en la muerte, que puede hacer que sus casas sean aún más peligrosas para las mujeres que las calles. A su vez, las madres les transmiten su estrés a sus hijos; se estima que entre 60 y 70% de las mujeres de Juárez les pegan a sus hijos y son abusivas psicológicamente.

* * *

En 2008 la violencia en Juárez alcanzó un nivel nunca antes visto y que nadie imaginó posible. Comenzó con la matanza indiscriminada de policías poco después del inicio del año nuevo: a mediados de febrero, 26 agentes municipales habían sido acribillados. Poco después los asesinos dejaron una nota en un monumento público que nombraba a los muertos y leía “para los que no creyeron”. Continuaba con la leyenda “para los que siguen sin creer”, seguida de una lista de diecisiete hombres que, según se entendía, serían los siguientes. Nadie podía explicar este súbito arranque de violencia, aunque el alcalde de Juárez, José Reyes Ferriz, diría más tarde que había recibido noticias de que una organización narcotraficante rival había declarado la guerra en contra de un poderoso Cartel de Juárez –aunque no explicó exactamente cómo fue que se enteró de esto. Según la teoría, este nuevo grupo estaba tratando de eliminar a los policías estatales que estaban en contubernio con el grupo de Juárez.

Para entonces, México ya estaba enfrascado en lo que el Presidente Felipe Calderón había declarado como una “guerra”. El año anterior había sido muy sangriento para otras regiones del país, ya que las alianzas y los territorios del narcotráfico se desplazaban y destrozaban y los cárteles peleaban entre ellos. Todo escaló hasta un alarmante nuevo nivel, y se adoptaron gestos grotescos como forma de enviar mensajes y de sembrar el terror público. Se colgaban cuerpos decapitados de pasos a desnivel; se cortaban manos. En el estado de Michoacán, comandos armados asesinaron brutalmente a doce policías federales que fueron enviados a investigar y dejaron sus cuerpos amontonados al lado de una carretera. Sin embargo, con el tiempo el pleito y el teatro escalarían aún más alto en Ciudad Juárez. Una de las víctimas fue crucificada en un árbol, la cabeza de otra se encontró con un sombrero de Santa Claus. La gente se olvidaría de los asesinatos de mujeres y Juárez se convertiría en el “epicentro de la narcoviolencia mexicana” o “la ciudad más mortífera del mundo”.

A diferencia de otras ciudades mexicanas plagadas de drogas, en Juárez no hubo una intervención formal del gobierno federal cuando comenzaron los asesinatos, de manera que el alcalde Reyes Ferriz y el gobernador de Chihuahua se unieron para encontrar respuesta. Se asumió que la policía era demasiado corrupta para ser capaz de controlar los asesinatos, muchos de los cuales eran dirigidos en su contra. Temerosos de que el poder de los criminales fuera mayor que su capacidad de mantener la seguridad de Juárez, el alcalde y el gobernador pidieron ayuda al Presidente Calderón. Para marzo habían recibido 2,000 tropas y con gran ceremonia lanzaron el “Operativo Conjunto Chihuahua”, una iniciativa multi-gubernamental que se esperaba sirviera como modelo para el resto del país. Pero a pesar de su presencia, para finales del 2008, el índice de asesinatos de la ciudad había aumentado cinco veces.

Yo volví a Juárez a tiempo para ser testigo de la última muerte del año –la víctima número 1,651 (para dar una idea de lo mucho que las cosas han empeorado desde entonces, en lo que va de este año ha habido alrededor de 2,450 asesinatos, cerca de 7,000 en los últimos tres años). Pero llegué a principios del 2009 para buscar patrones en esa masacre aparentemente azarosa que el Ejército mexicano era incapaz de detener, a pesar de que había tanques y Humvees por toda la ciudad. Lo que vi fue lo que la gente de Juárez ya sabía: que la violencia ahí desafiaba cualquier explicación tan simple como una guerra de cárteles. Varones que no tenían importancia alguna en el liderazgo de las organizaciones narcotraficantes eran asesinados salvajemente; hombres enmascarados se metían en centros de rehabilitación para drogadictos y masacraban a ocho, diecisiete, veinte personas. La gran mayoría de las víctimas de la ciudad eran hombres pobres entre los 18 y los 25 años de edad. Sus cuerpos se amontonaban en la morgue y sus asesinatos no eran investigados. Sus muertes hablaban de una ciudad en la que la guerra por territorios entre grupos criminales sólo sirvió como detonador de una forma de exterminio social de mucha mayor trascendencia y brutalidad. La vida en Juárez se había abaratado.

Pero quizá lo más inquietante de todo lo que aprendí en ese viaje fue que el gobierno mexicano estaba involucrado. La mayoría de la gente estaba demasiado asustada para hablar de esto, pero entrevistas y varias conversaciones confidenciales revelaron que el Ejército secuestraba a hombres jóvenes durante varios días y los sometía a torturas sañudas con el fin de sacarles información acerca del mercado de drogas interno de la ciudad. Nadie estaba buscando a un capo importante para atraparlo, lo que buscaban los soldados era información a muy bajo nivel, después de que los mandaron a Juárez sin inteligencia propia a partir de la cual trabajar. A veces las víctimas eran criminales de poca monta, y otras veces los elegían al azar simplemente por vivir en los vecindarios pobres que se suponían corruptos. El Diario de Juárez había reportado varias de estas historias de “abusos a los derechos humanos”, como los llamaron, pero lo que me impactó fue lo comunes y sistemáticas que eran. No fueron algunos casos especiales que se habían salido de línea; de hecho parecía haberse convertido en la estrategia de los soldados, ya fuera aprobada por sus comandantes o no. Algunas de las víctimas morían por las golpizas o jamás reaparecían, mientras que muchos otros eran enviados a la prisión local con cargos de drogas y armas, presumiblemente para elevar las cifras de casos de éxito de la operación. Y todos sabían esto en silencio –los examinadores médicos del Ejército, los procuradores locales y estatales, los abogados defensores, el personal de los hospitales a los que llevaban a algunas de las víctimas para evitar que murieran. El doctor de la prisión estatal –que generosamente me atendió por un virus estomacal que me dio por comer pescado malo– me dijo que todos los detenidos que llevaba el Ejército llegaban molidos a golpes. Y aun así, no había nadie que levantara la voz en su nombre, a excepción de un abogado instigador especialista en derechos civiles llamado Gustavo De la Rosa y algunos cuantos familiares de las víctimas, que levantaron protestas frente al campamento militar. En marzo de este año el alcalde de Juárez, Reyes Ferriz, visitó la Universidad de Texas en el campus de Austin, y cuando le pregunté por qué no decía nada en contra de los abusos insistió en que todas las personas que alegaban haber sido torturadas a manos del Ejército eran, cito: “delincuentes empedernidos”.

* * *

Hace varios años, un equipo de científicos sociales de Juárez publicó un diagnóstico integral de la compleja realidad social de la ciudad que ofrecía ideas para una intervención. La conclusión, bastante interesante, fue que a pesar de la enorme carencia de fondos para programas sociales, según su punto de vista la necesidad más grande era psicológica y afectiva. La gente de Juárez es de espíritu desdeñoso, pero en algún punto necesitan apoyo. Los autores del estudio preguntaron, en esencia, ¿es suficiente para una persona tener acceso a un trabajo en este mundo? ¿No existen otras cosas mucho más importantes, como el bienestar social, cultural y emocional?

Por eso me frustra tanto que hoy en día se dibuje a Juárez como el apocalipsis en escritos populares. Porque Juárez no es el infierno en la tierra, un lugar donde sólo las almas más valientes ponen pie. Juárez es una ciudad herida. Juárez es el ejemplo de lo que pasó cuando la gente fue despojada de su ciudadanía y olvidada por los gobiernos tanto de México como de Estados Unidos. ¿Podemos permitir que Juárez explote, o peor, que se repita en otro lugar? ¿Cuáles son las lecciones importantes que Juárez, la Ciudad de la Muerte, pero también la Ciudad de la Esperanza, nos enseña sobre la naturaleza de la democracia y las economías globales y la vulnerabilidad y la resistencia humanas? Cada persona tiene que contestarse esta pregunta a sí misma.

Sé que, en mi caso, la ciudad me ha dado mucho más de lo que yo le he dado a ella. En un foro reciente acerca de la violencia en la frontera que se realizó en Marfa, Texas, una moderadora le preguntó al escritor Charles Bowden por qué se molesta en regresar a Juárez. Pensé en lo afortunado que era que pudiera hacer esa pregunta –y que el panelista pudiera responder. Un millón de personas en Juárez –y decenas de millones de ciudadanos mexicanos– no se pueden dar ese lujo. Pero me fui a dormir con la pregunta, sabiendo que la respuesta estaba mucho más allá de mi sentido de responsabilidad periodística. Y esto es lo que concluí: la razón que yo concluí, la razón por la que regreso a Juárez, es porque la ciudad de la muerte me da una sensación de vida.