The Last Surrealist

Claire Joysmith

Título: Leonora,, Seix Barral / Planeta, México, 2011

Autor: Elena Poniatowska

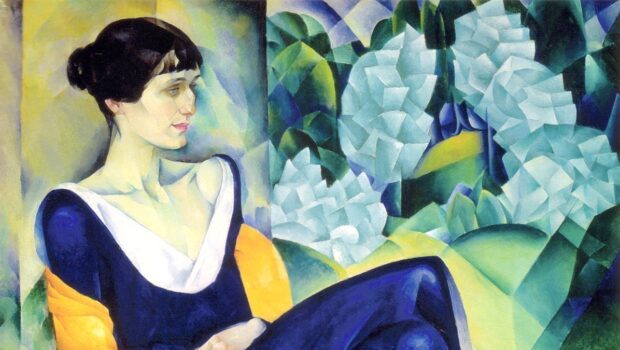

“The most beautiful sorceress to have survived into our times.” This is how Elena Poniatowska situates Leonora Carrington, the last living surrealist, who made “magic with each and every color,” as epigram on the map of the reader’s consciousness. Athough it takes Poniatowska over 500 pages to spread the “sorceress”’s life as a scintillating cobweb that mesmerizes the reader. This is no doubt one of the reasons Leonora was awarded this year’s prestigious Premio Biblioteca Breve in Spain.

In her epilogue-like piece Elena Poniatowska claims: “this novel…does in no way attempt to be a biography, but rather a free approach to the life of an artist by far out of the ordinary.” One might add that it takes a great and outstanding woman to write significantly and exhilaratingly about a great and outstanding woman. Leonora is certainly the case.

Elena Poniatowska met Leonora Carrington in the fifties and for half a century visited her as a friend. They shared a European upperclass childhood, English and French, a life in Mexico –loved by each in their own way– among other common interests. During that time Elena also interviewed Leonora with her finely spun talent webbed into an a daily-interview routine for many years. Although it is also Elena’s shrewd eye and generous heart for human nature’s myriad miracles, foibles and quirks, that makes Leonora such a great read.

The style is fresh, determined, poetic. The narrative trots, canters and gallops, perhaps in emulation of Leonora’s own core conviction and a leitmotif throughout the novel: that she is a mare under the guise of a woman. The narrative keeps pace with Leonora’s unbridled, dazzling, hyperbolic energy; it also fills pages with anecdotes and brushstroke cameos of well-known personalities that touched or were enmeshed in Leonora’s life at different times.

The publication of this novel celebrating Leonora Carrington has been uncannily timely: prior to her 94th birthday (April 6) and to her death (May 25). Leonora herself was not eager to receive awards and public homages, which she did anyway during her lifetime; although, as the novel makes clear, she most certainly enjoyed becoming the center of attention when it was worth provoking.

Leonora is depicted at the epicenter of several groups, in particular her participation as a major female exponent of the Surrealist movement, even though she maintained a distance from anything that would pin her down to any specific movement, dogma, religion, cult. Poniatowska writes: “Celtic mythology was Leonora’s only religion.” In the novel she stands on her own, often surrounded by people, some of them renowned, and by an extraordinary array of beings inhabiting her imagination, dreams and unconscious, that seeped into her paintings and writings. Poniatowska poignantly lays bare the solitude that at times gallops wildly within and at others drags her into dark caves and pits. Solitude remains faithful at the end of every tunnel.

At the core of Poniatowska’s portrayal is a careful objectivity that refrains from masking Leonora’s eccentricities and weaknesses, her self-obsession and self-pity, her stand- offishness and arrogance. Elena’s deep and translucid respect for Leonora helps her walk the thin line between being true to Leonora as she unabashedly was and exerting tactful caution regarding certain information: as Leonora would say to Elena, “let’s not get too personal.” This might be why Poniatowska left out of the novel some two hundred and fifty pages of the original manuscript, as she recently revealed.

Poniatowska’s complex portrait of an extraordinary woman and artist is remarkable: it unfolds Leonora’s personal and public transits through Europe, New York and Mexico, and various ambiances that tic-tocked in Leonora’s ever-surprising destiny. Such as her childhood in an aristocratic and stiff-upper-lip family in England, dappled with the wisdom of her Irish grandmother and her beloved Irish Nanny (who understood Leonora’s clairvoyant gifts), both of whom instilled in her love for all Celtic and for the Sidhes who would keep her company and find their way into her paintings. Rebel at an early age, demanding her brothers’ freedom while she was trained to be a good wife, she was expelled from several schools run by nuns and did not live up to her parents’ expectations as a court débutante at Buckingham in London.

Another ambiance depicted in detail is her sizzling life in Paris where her true vocation as an artist was unbridled. Strikingly beautiful, having just turned 20, she met Max Ernst, 27 years older than her, who called her “the wind’s bride,” both living out to the hilt what Surrealist André Breton named “l’amour fou.” At the time she met and mingled with prominent Surrealists and personalities such as Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Breton, Paul Éluard, Man Ray, Leonor Fini, Marcel Duchamp, among many others.

When Ernst was arrested and sent to a concentration camp, chaos and despair were unleashed in Leonora, still in her early twenties; her quasi-visionary madness, so the novel suggests, had its affinity with a political clarity, a frenzy not unrelated to the chaos and despair in a wartorn, nazi-infested Europe. She was interned, as per her father’s instructions, in an asylum in Spain, a terrifying experience that marked her deeply and which she was to recount much later in the hundred pages of her memoir titled Down Below.

Also depicted in detail is her escape –it could almost be an excerpt from a work of fiction– from being sent to another sanatorium in South Africa. During a stop in Lisbon, with nothing but pocket money to buy some gloves, she eluded her caretakers and took a taxi to the Mexican Embassy where the wellknown Mexican diplomat and journalist Renato Leduc she had known previously in Paris took her under his wing. Shortly after they would marry and sail to the U.S. but not before Leonora’s destiny with Max Ernst was played out in Lisbon and later in New York, now he was Peggy Guggenheim’s lover. The novel suggests that Leonora’s decision to take an unpredictable route away from the Surrealist crowd in decadence, was to go to Mexico with Leduc, although they would soon divorce.

Leonora’s life in Mexico for over 60 years becomes in the novel richly entwined with an amazing array of people and events. Her life turn a turn when she met and later married Hungarian Jewish photographer Csizi Wiesz, known as Chiqui, and discovered the centering bliss of motherhood with the birth of her two sons, Harold Gabriel or Gaby and Pablo. Also life-changing was the happy meeting in Mexico with Spanish surrealist painter Remedios Varo, her “twin soul” who “[taught] her to pronounce Quetzalcoatl” and was to become her dearest and closest friend. British eccentric millionaire Edward James with his yellow socks, saved the family economy by becoming her enthusiastic admirer and mentor for many years. She also knew and mingled with other personalities such as Kati Horna, Eva Sulzer, Alice Rahon, Herbert Read, Wolfgang Paalen, Gunther Gerszo, Octavio Paz, Ignacio Bernal, Luis Buñuel, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Laurette Séjourné, Diego Rivera (of whose frescoes she is quoted as saying in English “They are not exactly my cup of tea”), Frida Kahlo, and others.

What Elena Poniatowska is also able to regale the reader with in the part of the novel centered in Mexico, is her ability to succinctly cameo not only people but places, historical moments and to extract precious filaments from the rich tapestry of Mexican culture and history. The binocular effect in which biographical protagonist and narrator-writer merge into a single perspective is prevalent in the novel and brings the reader lines such as these: “in Mexico, miracles, like idols, come out from even under the stones” (324), in Mexico “to be a foreigner is a stigma,” “This land that at each moment expels the remains of an extraordinary culture moves Leonora.” Other statements, though, are clearly direct quotations from Leonora: “Mexico has made me what I am because had I stayed in England or in Ireland I would not have yearned for the world of my childhood as I have here [in Mexico],” “What I paint is my nostalgia.”

Leonora is, in a sense, also about how Mexico homed a wonderfully out of the ordinary woman and outstanding British artist, as it has done for many foreigners at different times in history. And one could venture to say that, as happens with novels, it’s as much about Leonora as it is, in some ways although not in others, about Elena, who has made Mexico her most beloved home.

Leonora is, however, always graciously granted center stage.

Leonora Carrington will not be forgotten for many reasons. One is no doubt this remarkable book which will most certainly find its way very soon into English-language bookshelves in the U.S., UK and elsewhere. An ode to Leonora’s life, talent, suffering, inner strength, eccentricity, uniqueness, keen wit and sense of humor, this novel is a valuable gift to us readers for which we have Elena Poniatowska to graciously thank.

Posted: June 12, 2012 at 3:47 pm