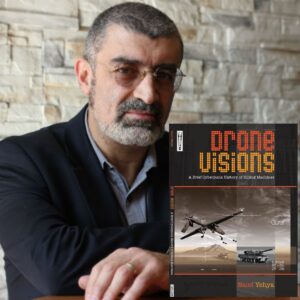

Drone Visions: A Brief Cyberpunk History of Killing Machines

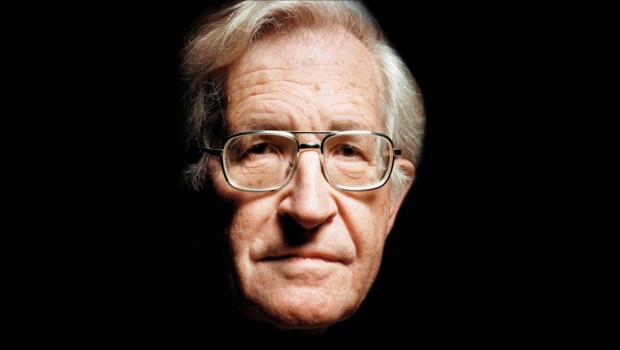

Greg Walklin

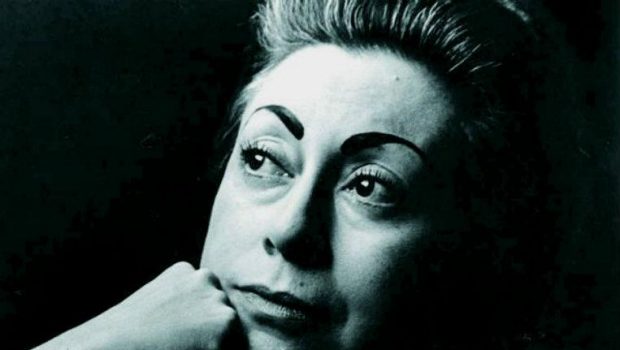

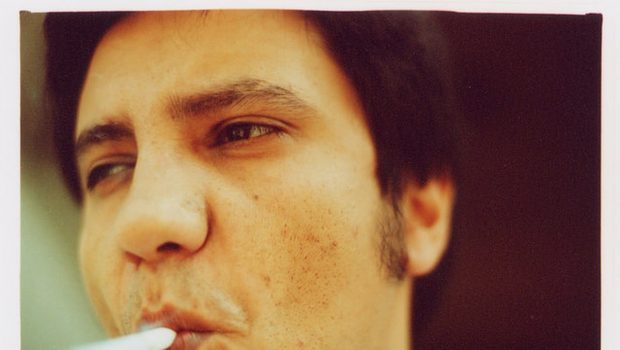

Naief Yehya

Hyperbole Books

Translation by Uriel Murillo Sosa, Lorenzo Antonio Nericcio, and the author

It is a truism that September 11, 2001 changed the world. But like any major world event, there were changes and repercussions that remain less obvious, or at least less discussed. It was only after the Twin Towers fell, for example, that the United States decided to start seriously arming unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). These drones shifted from surveillance tools to remote killing machines, piloted from pods in the Nevada desert, or from offices in suburban strip malls, becoming the vanguard of the War on Terror.

Naief Yehya’s book Drone Visions: A Brief Cyberpunk History of Killing Machines centers on this change. Part film criticism, part cultural history, part political panegyric, Drone Visions offers an intriguing analysis of how killer drones and artificial intelligence systems have been portrayed in visual media.

In the book’s strongest sections, Yehya places special emphasis on the Blade Runner, Terminator, Mad Max and Alien franchises. He holds them to be forerunners in the artistic exploration of killing machines and cyberculture…

In the book’s strongest sections, Yehya places special emphasis on the Blade Runner, Terminator, Mad Max and Alien franchises. He holds them to be forerunners in the artistic exploration of killing machines and cyberculture—their initial installments as harbingers of predator drones and hellfire missiles. Yehya writes:

“The digital revolution that is devouring the entirety of culture was defined within the popular imagination through these stories of cybernetic organisms, planetary devastation, and artificial beings that rebel against the destiny programmed by their creators.”

Stories of creation rebelling against creator are as old, of course, as Genesis. Even Aristotle and Montaigne wrote about how it was inevitable that fathers would love their children more than the children loved them back. And from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein on, science fiction has explored what happens when the creator doesn’t love the creation, and the creation either desperately wants love back or—as the case in Alien —is just hellacious and murderous.

Such dramatic exploration of this idea is the most nuanced and complicated in Blade Runner and its excellent (if poorly titled) sequel, Blade Runner 2049. Yehya says that Ridley Scott’s original film—itself a result of a production so troubled it was amazing the film was finished—is “a brilliant reflection on technology, photography, and architecture,” and “a paraphrase of Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost.’” He notes the movie is “full of abysmal visions” with “steel, glass, and metal canyons…” and all kinds of balconies and parapets. By contrast, the Replicants, only allowed four years of life, yearn for depths of humanity they cannot achieve. The ending of the film, taking place on a high ledge in blinding storm with the late Rutger Hauer’s famous last words, is a perfect example of how Jordan Cronenweth’s cinematography works in perfect conjunction with the story. Yehya also delves deep into Denis Villeneuve’s sequel, finding it to be “a prodigious philosophical allegory and a visual delight that makes every citation and reference a joyous homage.” The extent the Replicants possess humanity or something like it—in Yehya’s words, “dilemma of a ‘species’ fighting to prove its humanity”—is the central question of both films.

In both the Terminator and Aliens franchises, though, the creations are more like automatons: killing machines ready to do their makers in. James Cameron’s The Terminator is “an oracle of the human condition within the times of cyberculture.” The terminators in the film series are not so different from aerial killing drones used to assassinate terrorists; and both end up killing many innocents. Meanwhile, besides the conniving androids, the aliens in the Alien films are sort of organic killing drones unleashed by “Engineers” (quite hyper-male looking beings) across the universe, only to be fought by female protagonists. (Yehya: “Not for nothing are there those who consider it [Alien] a film about fear of male rape.”)

While Skynet is still fiction, and while artificial intelligence has not passed the Turing Test, civilization is now poised at a time when we employ machines that allow us to kill from thousands of miles away, and wage wars with no possibility of casualties. It is possible we are near the inception of some dystopia already imagined by science fiction. September 11, Yehya holds, brought a “new era” of “hyper surveillance, intimidation of the citizenry, and the imposition new laws that gave immense power to the security apparatus.” These changes bring new dangers, use political ends to justify killer drones, and are risking important and unique aspects of our humanity.

With significant cinematic erudition, Yehya also explores other visual media that has dealt with and reacted to these post-9/11 military and political shifts, including Eye in the Sky, Good Kill, and Laura Poitras’ stirring My Country My County, among others, before expanding into discourses on drones in pornography, photography, video games, and apps.

While the translation by Uriel Murillo Sosa, Lorenzo Antonio Nericcio, and the author renders lucid English, the book suffers from some sloppy editing, with distracting typos and factual errors (the Mad Max sequel Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome is alternately called Beyond Thunderstorm and Beyond the Thunderdome on the same page, for instance); furthermore, while precise in his aesthetics, Yehya can sometimes be conclusory on history and politics (he pronounces on one page that “the majority of humanity lives in abject misery”). Overall, though these examples are mostly distractions from otherwise rich, erudite analysis.

Technology has changed us, Yehya writes, making us “biological drones, aware and absent.” He continues: “We navigate, share, and make decisions with tools controlled remotely by corporations of ambitions and interests that are different, and, at times antagonistic, to our own.” This warning, ultimately, is what we are fighting against—retaining our humanity as we fill the world with more machines. It is what the Tyrell Corporation, the creators of the Replicants, in their brutality, overlooked; it is what the terminators and aliens are so ruthlessly trying to eliminate; and it is what, in “Mad Max,” nearly the entire fuel-obsessed human race has forgotten.

According to Yehya, one favorite pastime of drone pilots flying UAVs over Afghanistan was to try to glimpse Afghanis having sex on their roofs. Other pilots have fought against the claim by the military that they cannot have PTSD from operating drones because they were not at the locus of combat. “We have lost,” Yehya concludes, “all capacity for astonishment and shame in the face of the routine spectacle of men, women and children dehumanized and torn to pieces in distant corners of the world…”

Indeed, “remote assassination is run-of-the-mill,” Yehya writes. Many of us know that—it should be obvious by now—but when ones to really begin to think about that, about what that means, it is hard not to see the Blade Runner or Terminator franchises as Cassandras, trying to warn us of the future while we blithely stare into our phones. In that way, Drone Visions crystallizes a dark future.

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing

Posted: August 2, 2020 at 10:00 am