Egypt Two Years Later

Egipto dos años después

Heba Gowayed

Political change, particularly grassroots revolutionary change, is often a non-linear, messy process. From 1989 we learned that even with the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union the economic and political realities of countries of the Eastern European block did not undergo a complete overhaul overnight; nor did they move at the same pace or change in the same ways. Over the past two decades the majority has moved towards increased transparency and democracy–with the Ukraine continuing to trail behind. We learn from Iran’s 1979 revolution that the beginnings of an uprising do not determine its end. What began in 1977 as a rejection of a Monarch’s autocracy with secular and religious support led to another form of autocracy, religious in color, which has been faced with yet another set of challenges to its legitimacy in recent years. It is also difficult to define the beginning of what is revolutionary action. The movements of activists in Latin America throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, and more recent movements like Mexico’s YoSoy132, are a call for respect; but are they the beginnings of real systemic reform, or perhaps a continuation?

I was asked by Literal to revisit the changes that have occurred in the Arab World over the past two years, since the start of the uprisings, and to use this context to reflect on movements in Latin America. As an Egyptian citizen, I have decided to focus predominantly on my own country’s process. I begin with a rejection of the notion that the revolution has ended in Egypt. This is not a piece commemorating a past event, but rather a reflection on the dimensions of the process of Isqat Al-Nizam, bringing about the downfall of a system.

William Sewell teaches us that social processes take time to work themselves out –making the defining of the contours of “revolution” difficult for the observer. On the second anniversary of the start of Egypt’s uprising, celebrating the initial eighteen days and the removal of Mubarak holds a certain allure. However, that would be missing the point, because the public squares remain full: indeed, they have not been empty for the past two years. Egypt’s streets have set the stage for constant cyclical challenges to the myriad obstacles to democracy. They also remain the site of violent clashes and sacrificed lives. Over the past two years I have read countless articles about how the revolution has been co-opted by members of the former regime, by the Military, or by the Muslim Brotherhood. Instead, I argue that with each attempt at co-optation, there is a constant pushing back by activists who reposition themselves against each threat, changing their chants from “down with Mubarak” to “down with Tantawi” and finally “down with Morsi.” The driving force of these crowds is a commitment to the realization of dignified lives; to have under just law their political voice and basic well-being recognized. I reject the argument that these protestors are a weak, liberal elite. Instead, I turn to one of the few empirics available to me to argue that despite the final victory of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, in May 2012 the largest contingency of voting in the first stage of elections–forty percent–was for candidates that did not belong to Islamist parties and did not belong to the former regime.

Still, and particularly in the case of Egypt, the goals of the revolution are far from being recognized. Politically, we continue to live under undemocratic institutions. Our president pushed through the passage of a botched and disjointed constitution overnight which serves as a weak blueprint for upcoming parliamentary elections, already anticipated to be undemocratic. The self-imposed introversion of the military, which has full control of arms and full autonomy without civilian oversight, is a frightening reality. Additionally–much like our Latin American counterparts–we continue to struggle against steadily increasing levels of poverty, expensive foodstuffs, and the privatization of our once public education, resulting in inequities that riddle our society.

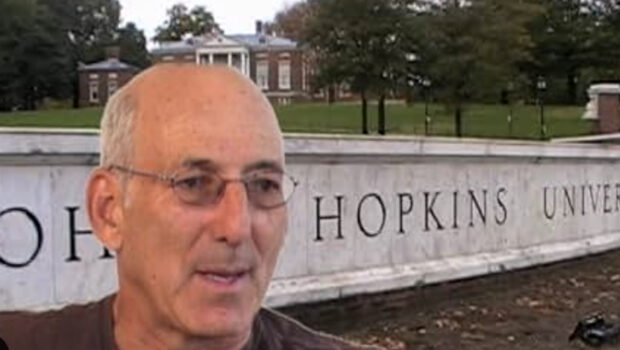

What I will celebrate today is that throughout the Arab World–in Tunisia, where Bouazizi lit with his own body the fire of resistance; in Yemen and Libya, where militants have taken up arms; in Egypt with its ongoing struggle; or even in Syria, where those fighting for freedom are massacred as the world watches–the scope of the possible is forever being expanded. People can no longer be silenced, and there is no going back. While we focus on the start of these revolutions as being in the winter of 2010-2011, regional experts may disagree. Kamal Abu-Eita, the renowned labor activist, contends that not only is the revolution not over, it started with labor actions that began decades earlier. Joel Beinin, professor of Middle East History at Stanford, argues conversely that not only has it not ended, it has not yet even begun. As we watch the student protests in Chile, Mexico, Colombia and Puerto Rico, we are seeing calls for dignity, which though different in each country, and different in trajectory and goals from the Arab context, all hold a firm commitment to fight for the realization of a better life for citizens. If there’s something that we’ve learned over the past two years, it’s that change is possible, albeit messy; and also that change is difficult to anticipate, or even to recognize.

Traducción al español de David Medina Portillo

El cambio político, particularmente el de base revolucionaria, es a menudo no-lineal y desordenado. Después de 1989 aprendimos que aun tras el final de la guerra fría y la caída de la Unión Soviética, la transformación de la realidad económica y política de los países de Europa del Este no se realizó plenamente de la noche a la mañana. Hoy tampoco se mueven al mismo ritmo ni cambian de la misma manera. En las dos décadas pasadas, la mayoría del bloque ha optado por una mayor democracia, con la excepción de Ucrania, que sigue a la zaga. Asimismo, con la revolución iraní de 1979 entendimos que el inicio de una revuelta no determina su fin. Aquello que en 1977, y con el apoyo secular y religioso, comenzó como un rechazo a la autocracia de un monarca, condujo a otra forma de autocracia religiosa, esa que en los últimos años enfrenta nuevos desafíos a su legitimidad. Por lo mismo, es difícil definir los orígenes, el momento en que nace una acción revolucionaria. Los movimientos activistas en América Latina durante las décadas de 1990 y 2000, junto con los más recientes, como el YoSoy132, constituyen un llamado al respeto ciudadano, ¿pero son el principio, o la continuación quizá, de una reforma real del sistema?

Literal me pidió analizar los cambios ocurridos en el mundo árabe en los últimos dos años –desde el comienzo de las revueltas–, contrastándolos con los movimientos de América Latina. Como ciudadana egipcia decidí ocuparme, principalmente, del proceso en mi propio país. En este sentido y para comenzar, rechazo la idea de que en Egipto la revolución ha concluido. Las líneas de este texto no buscan conmemorar un acontecimiento pasado sino, más bien, son una reflexión sobre las dimensiones del proceso de Isqat Al-Nizam, el que provocó la caída de un sistema.

William Sewell enseña que los procesos sociales se toman su tiempo para trabajar –perfilan rasgos difíciles de captar para el observador de una “revolución”. En el segundo aniversario, se vive cierto hechizo por los primeros dieciocho días de la revuelta egipcia y la posterior retirada de Mubarak. Sin embargo, se pierde de vista que las plazas siguen ocupadas y no han estado vacías estos dos años. Las calles de Egipto son el escenario de constantes desafíos a los obstáculos que enfrenta la democracia. Continúan siendo también el lugar natural de violentos enfrentamientos y el sacrificio de vidas. En los últimos dos años he leído innumerables artículos sobre cómo la revolución ha sido cooptada por miembros del antiguo régimen, por militares o por la Hermandad Musulmana. Por mi parte, sostengo que con cada intento de cooptación hay una firme embestida por parte de los activistas, quienes se reconstituyen ante cada amenaza, pasando de la consigna “¡Abajo Mubarak!” a la de “¡Abajo Tantawi!” y, finalmente, “¡Abajo Morsi!” La fuerza motriz es su compromiso con la realización de una vida digna y, bajo una ley justa, en pro del reconocimiento de su voluntad política y bienestar básico. Rechazo el argumento de que los manifestantes son una elite liberal débil. En cambio, recurro al poco empirismo disponible para argumentar que, pese a la victoria final de Mohamed Morsi de la Hermandad Musulmana, en mayo de 2012 el mayor contingente de la votación durante la primera etapa de las elecciones –40 por ciento– fue para los candidatos que no pertenecen a los partidos islamistas y tampoco al antiguo régimen.

Sin embargo, y particularmente en el caso egipcio, los objetivos de la revolución están lejos de ser reconocidos. Políticamente, seguimos viviendo bajo instituciones no democráticas. Nuestro actual presidente dio impulso a la aprobación de una chapuza, propiciando la desarticulación de una Constitución que servirá como modelo débil para las próximas elecciones parlamentarias, las que de antemano serán antidemocráticas. El autoimpuesto recato de los militares, que cuentan con el control total de las armas y una autonomía sin supervisión civil, es una realidad aterradora. Además –igual que nuestra contraparte latinoamericana– continuamos luchando contra niveles de pobreza cada vez mayores, bienes alimenticios caros junto con la privatización de nuestra educación pública –todos causantes de inequidades que laceran a nuestra sociedad.

Hoy hay que celebrar que en el mundo árabe los límites de lo posible se están expandiendo –en Túnez, donde Bouazizi encendió con su cuerpo el fuego de la resistencia; en Yemen y Libia, donde los militantes han tomado las armas; en Egipto, con su lucha aún en curso; o incluso en Siria, donde los combatientes por la libertad son masacrados mientras el mundo observa. La gente ya no se puede detener; no hay vuelta atrás. Si coincidimos en que el estallido de estas revoluciones comenzó en el invierno de 2010-2011, algunos expertos de la región podrían no estar de acuerdo. Kamal Abu Eita, reconocido activista laboral, sostiene que la revolución no ha terminado sino que, incluso, comenzó con la acción sindical de décadas pasadas. Joel Beinin, profesor de Historia del Medio Oriente en Stanford, afirma que, en efecto, no sólo no ha terminado, aunque tampoco ha comenzado… Al observar las protestas estudiantiles en Chile, México, Colombia y Puerto Rico presenciamos reclamos de dignidad que, pese a las diferencias de cada país –distintas también en trayectoria y objetivos del contexto árabe–, comparten su compromiso firme en favor de una mejor vida ciudadana. Si algo hemos aprendido en los últimos dos años es que la transformación es posible, aunque azarosa; también que el cambio es difícil de prever o, incluso, reconocer.

![Entre Pink Floyd y el INAPAM [1]](https://literalmagazine.com/assets/patti-620x350.png)