Between Earthquakes

Jorge Iglesias

Author: Alejandro Zambra,

Title: Ways of Going Home,

Publisher House: Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

New York, 2013

Trans., Megan McDowell

Even though Roberto Bolaño produced most of his works in Spain, it is his name that usually comes up when speaking of Chilean literature. Whether we agree with the consensus or not, The Savage Detectives and 2666 have become canonical texts of Spanish American literature, and even of world literature. Not long after these epic novels appeared,

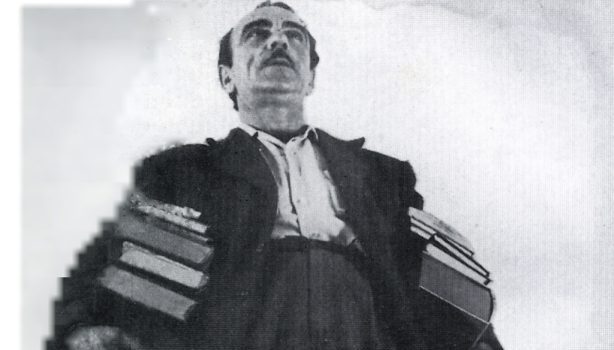

a young Chilean author began to publish brief narratives that can be classified as novellas, that is, as examples of that anti-epic form the delights of which more and more readers–and authors–are discovering. Although Alejandro Zambra (Santiago de Chile, 1975) began his writing career as a poet, he is known mainly for his fiction. All three of his novellas have been translated into English. Bonsai (2006), which received the Chilean Critics Award and was made into a highly satisfactory film, was followed by The Private Lives of Trees (2007), which many considered to be a companion piece. Zambra’s latest novella, Ways of Going Home, can easily be seen as the third installment of a trilogy about young middle-class santiaguinos with literary inclinations.

One need hardly mention that the novella as a genre has flourished in Latin America in the past few decades. César Aira and Mario Bellatin, authors of How I Became a Nun (New Directions, 2007) and Beauty Salon (City Lights, 2009) respectively, have devoted themselves almost exclusively to the novella, perpetuating a tradition that goes back to the nineteenth century, and which includes classics such as The Invention of Morel, Pedro Páramo, No one writes to the colonel, and Aura, to name only a few. Concerned as it is with the reexamination of a particular situation, the novella is the perfect genre for a narrative that deals with the past, more concretely with a childhood spent in the shadow of the Pinochet regime. The narrator of Ways of Going Home looks back on his childhood and meditates upon the novel he is writing, which is, of course, the one that the reader holds in his or her hands. Zambra’s trilogy of novellas proves that, despite the many experiments of postmodernism, metafiction is not a thing of the past, and that it is still possible to write gracefully about the act of writing. Zambra is a master of understatement. The melancholy minimalism of Bonsai, however, gives way in Zambra’s latest novella to the nostalgic prose of memory, a slightly more elaborate, evocative style that Megan McDowell–who has also translated The Private Lives of Trees–captures with great success in her translation. The brief chapters that compose Ways of Going Home are individual episodes, the accumulation of which eventually allows the reader to see the complete picture. Divided into four parts, the novella alternates between the past and the present, between the child to whom Pinochet was just a man who hosted an annoying TV show, and the young man trying, through writing, to make sense of a life lived as a secondary character. In a simple, suggestive style, Zambra tells the story of how the dictatorship affected those who were “too young” for it. If heartbreak is the mood that operates in Bonsai, and The Private Lives of Trees is marked by expectation, Ways of Going Home transmits that sense of sadness at the passing of things that the Japanese refer to as mono no aware.

Ways of Going Home is a story between earthquakes, beginning and ending with one. Between these violent, unsettling events that remind us of the precariousness of our existence, memory takes place. We often visit the land of memory–to borrow a phrase from Felisberto Hernández–unexpectedly, as if shaken into and out of the past. Zambra’s third novella is both a trip to that land and an examination of the journey itself. It is also an agreeable companion to Zambra’s previous works of fiction, and above all, a reason to wait for his next.

Posted: July 8, 2013 at 4:54 am