A Cult Classic

Liliana Valenzuela

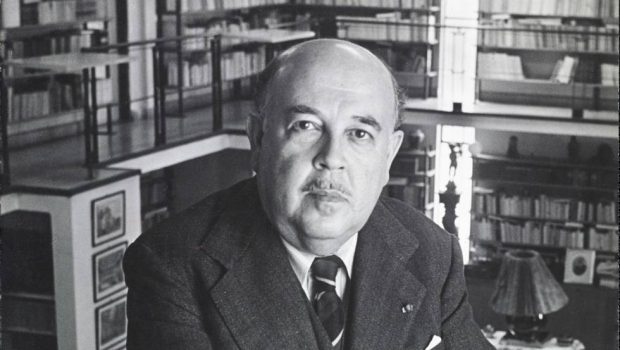

Guillermo Rosales,

Guillermo Rosales,

The Halfway House,

New Directions, New York, 2009.

Translated by Anna Kushner

Preface by José Manuel Prieto

To walk into The Halfway House is to inhabit this particular microcosm of misfits somewhere in Miami, people for whom “nothing more can be done.” The experience can be harrowing, and yet, at times, it appears as though Eros might win over Thanatos. We follow the life of William Figueras, a Mariel refugee from Cuba with a history of mental illness (much like the author himself), as he descends into this modern day inferno, yet he’s not crazy, but rather deeply aware of the abuse and the sordid conditions of his new “home.” He, who “by the age of fi fteen [had] read the great Proust, Hesse, Joyce, Miller, [and] Man” stays afl oat by reading from a book of English poets, whose poems are peppered throughout the novel, until he meets Frances, whose body “while cheated by life, still has some curves.” She, like Figueras, was once an enthusiastic young Cuban communist teaching peasants to read, but has since become “broken inside.” But Frances is also an artist, she carries around a folder with her drawings, “worthless things,” but Figueras is deeply moved by them and recognizes that like him, she is redeemed by art. For a moment, there’s a glimmer of hope as the pair plots to escape the nut house in order to become a normal couple, before coming to the unexpected ending.

The story is told in sparse, lyrical language, beautifully and accurately rendered into English by Anna Kushner. The most grotesque characters are sketched with one or two quick strokes, yet we feel we know them. The narrative is further enhanced by Figuera’s vivid dreams, for instance, his dream of Fidel in briefs and underwear refusing to leave a white house, while Figueras shoots at it with a cannon. The excellent preface by José Manuel Prieto provides context and proposes “the condemnation of the ravages of totalitarianism” as the central theme of the novel. He also informs us that while this book won the Letras de Oro (Golden Letters) award in Mexico in 1987, it was not well received until reissued in Spain in 2003 under the title of La casa de los náufragos (The House of the Shipwrecked) to great acclaim. And that the 2002 French edition published as Mon Ange (My Angel) “was a resounding success.”

In a little over one hundred pages, Figueras makes us face the minute moral calibrations that separate victim from victimizer, a realization that haunts him, “I regret having beaten the old one-eyed man. But it’s too late. I’ve gone from being a witness to being complicit in what happens in the halfway house.” A little-known author who destroyed most of his work before committing suicide in 1993 at the age of 47, Guillermo Rosado is deserving of more attention as evidenced by this intense, raw, little jewel of a book. The Halfway House has the potential to become a cult classic on a par with The Burning Plain, The Kiss of the Spider Woman, or Pedro and the Captain.

Posted: April 18, 2012 at 9:12 pm