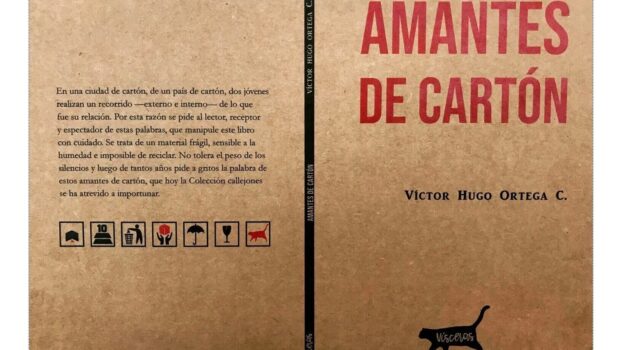

Amantes de cartón

Bridget Ellen McNulty

Personal and political vulnerability collide in Víctor Hugo Ortega’s depiction of love and loss in 21st century Santiago de Chile

A couple wander through the streets of a polluted metropolis, tracing the steps of their broken relationship to discover where they took their wrong turning. Despite the speaker’s often fierce belief in their ability to distance themselves from the vices of their environment, it is impossible not to read Víctor Hugo Ortega’s Amantes de cartón/Cardboard Lovers as a love/hate letter to a cardboard box of a city which breeds fragility in its inhabitants through its structural inequality. Following the publication of his debut poetry collection Latinos del sur, Ortega’s second poetry collection was born into a Santiago de Chile gripped by a state of emergency, with civil protests against the increased cost of living, privatization and inequality hitting global headlines. What makes Ortega’s collection so compelling is the pervasive sense that no matter how hard the lovers try to resist identification with the city they inhabit, their love for its flaws will pull them back into its fold, and whilst we may know how the story ends, we cannot look away.

The collection begins with El ojo de Santiago/The eye of Santiago, looking upon the lovers with ‘indiferencia contaminada/polluted indifference’, much like the Gatsbyesque eyes of Doctor T J Eckleburg overlooking a moral wasteland, yet transported to a 21st century Santiago they symbolize both the futility of the lovers’ attempt to shield their relationship from the corrupting eyes of the city, and provide a bleak reminder that modern day surveillance culture renders this an impossible task. Ortega’s subtle manipulation of the speaker’s voice throughout portrays the disintegration of a relationship from the invincibility of the collective ‘nostros/us’ to the vulnerability of the ‘tú y yo/you and I’ who gradually become subsumed by the city’s gaze. Ortega’s language is simple yet never stark, its artistry lies in its ability to transport the reader to an otherworldly land of cardboard people whilst simultaneously imbuing it with intimate recollections of home, even if at times the reader may wish for more than just a glimpse into the lives of the ‘mujeres y hombres del país de cartón/women and men of the cardboard country’.

‘Cartón/cardboard’ is applied metaphorically throughout the collection to depict the fragility of the lovers’ relationship and their city, however Ortega’s choice of a material known for its toughness and ugliness also suggests a stubborn resistance to let go. As a result, the ‘cuchillo cartonero/cardboard knife’ with which the lovers’ arms are sacrificed to each other through embraces in Nos faltaban manos/We lacked hands leaves an indelible mark. The city is omnipresent throughout the collection, Ortega’s use of vernacular reminding us of its presence without the need to allude to it. He even invents the verb ‘cartoniza[r]’ to illustrate how relationships are condemned to be welded by cardboard in this ‘país de cartón/cardboard country.’ Despite this, it is the lovers’ experiences of the city which propel the narrative, and poems such as Huérfanos/Orphans offer the reader moments of genuine tenderness between couple and place as they wander through some of the city’s most recognizable landmarks to ease the speaker’s grief. There is something painfully satisfying in their choice to walk on the sunny side of the street, content in their knowledge that they always burn their faces when they do. The stubbornness of young love is relatable, yet this fierceness of character is weaponized in Qué será de este cabro/What will become of this kid, as the speaker’s protectionist attitude towards his town is exposed as a source of resentment towards the lover, fueling their separation. Love has become a ‘sistema de estrategias/system of strategies’ in Santiago and ultimately the lovers must choose a side.

Where Ortega’s collection excels is in his portrayal of the simultaneous freedom and insecurity that this fragile, temporary kind of love can offer. The lovers are as much ‘cardboard lovers’ as ‘lovers of cardboard’. In Acción poética/Poetic Action they revel in having nothing to plan and having exhausted their own poetry, they mock the poetry of others. Yet the poetry on these walls has more permanence than the cardboard fortress they have built to shield their love from the outside world. To call Amantes de cartón millennial poetry would be to undermine the universality of its themes of love and loss, nevertheless there is a certain generational specificity in La preocupación por el futuro/Worry for the future in which the insecurity of both present and future stunts the growth of their relationship to the extent that the couple doubt that love was really there to begin with. It is not just a generational angst but also a cultural one as beauty spots in which the lovers choose to meet convert into images of the city’s deprivation. They find comfort in the shelter of the past, cowering in the shells of buildings that have lived former lives. The speaker even admits that their love was conceived in ‘un bar que ya no existe/a bar that no longer exists’, giving us the sense that the foundations of their relationship are being lifted from under their feet, opening the way for doubts to creep in: doubts that their love never really existed, that their own narrative is fragile, de cartón. It feels almost convenient then when their own narrative is snatched away from them by an impersonal narrator in the penultimate poem of the collection. They cannot escape their personal love story being welded to the complex narrative of the city they inhabit, the outpouring of emotion in Tanto color/So much colour as much a love letter to Santiago and all its vulnerabilities as it is to each other.

Ortega is renowned principally for his short story collections and nowhere is his ability to create a compelling narrative more evident than in the cathartic release of suppressed memories in the final throes of the collection. The ‘Torre Titanium/Titanium Tower’, one of Santiago’s largest skyscrapers and symbolic of the wealth that the lovers bypass in their wanderings through the city’s less affluent streets, is a poignant setting for Dos mil ciento noventa/Two thousand one hundred and ninety, in which the speaker finds themselves in a lift together with their lover years after their separation, physically close but emotionally distant. Making a last-ditch attempt to communicate with their lover, Ortega creates a ‘will they won’t they’ moment of real drama in which the reader, albeit against their better judgement, wills the speaker to forge the connection, if only to satisfy their own curiosity. What follows is a maddening battle of tenses in which the vulnerability of a new narrative collides with the endurance of deep-rooted memories.

Ortega’s quietly assured portrayal of a love affair in all its imperfections, from the invisible yet enduring marks left by passionate embraces, to the desperate craving to assign blame when it is impossible to do so, is one to which we can all relate. Played out against the backdrop of a ‘cardboard’ city in which monotony threatens to overwhelm color, the personal cannot be separated from the political in this fragile package of a collection. In the midst of a global pandemic, Amantes de cartón is a poignant reminder that the societal structures on which we depend, and often believe to be permanent, are just as vulnerable as ourselves.

Bridget Ellen McNulty is a British-Irish reviewer interested in contemporary Latin American literature. She graduated from Oxford University in English Literature and Modern Languages. She has worked as an English teacher in Madrid and Santiago de Chile and was a regular contributor to Talleres Barravento, an independent educational project with the mission of promoting Latin American creative arts. Bridget currently lives in the UK and works as a higher education professional at Imperial College London. In her spare time, she is a creative writer and sings with the BBC Symphony Chorus. Twitter: @McNultyBridget

Bridget Ellen McNulty is a British-Irish reviewer interested in contemporary Latin American literature. She graduated from Oxford University in English Literature and Modern Languages. She has worked as an English teacher in Madrid and Santiago de Chile and was a regular contributor to Talleres Barravento, an independent educational project with the mission of promoting Latin American creative arts. Bridget currently lives in the UK and works as a higher education professional at Imperial College London. In her spare time, she is a creative writer and sings with the BBC Symphony Chorus. Twitter: @McNultyBridget

Posted: June 4, 2020 at 8:54 pm