An Interview With Alison de Lima Green, Curator, and Enrique Mallén, Founder of the Picasso Project

Debra D. Andrist

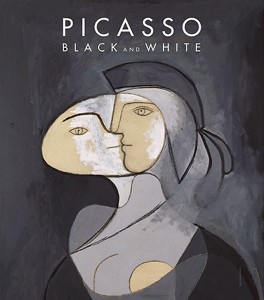

While Literal is ordinarily dedicated to Voces Latinoamericanas, extraordinary converging circumstances inspired this interview highlighting a voice from the Madre Patria, the mother country–Pablo Picasso of Spain. Not only has Picasso had such impact everywhere artistically, but the Museum of Fine Arts/Houston (MFAH), is the spring 2013 locus of two exhibitions of mother-country art, Portrait of Spain: Masterpieces from the Prado, and Picasso Black and White. A geographic coincidence, the Picasso Project, the most comprehensive on-line source on the life and works of Picasso https://picasso.shsu.edu/ is based nearby at Sam Houston State University (SHSU).

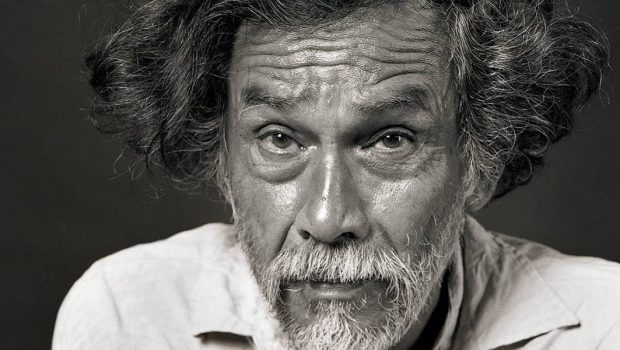

Alison de Lima Greene (ALG), MFAH Curator of Contemporary Arts & Special Projects, is handling the MFAH’s presentation and interpretation of Picasso Black & White, a show that originated in New York at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Dr. Enrique Mallén (EM) is Founder and General Editor of the Picasso Project and Professor of Spanish at SHSU.

* * *

Debra D. Andrist: Alison, how/why were the works selected for this exhibition?

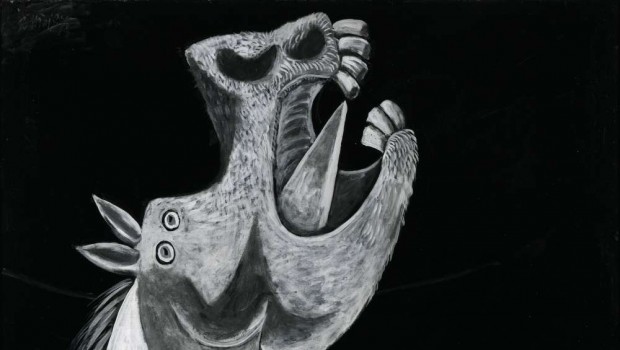

Alison de Lima Green: For Houston, we built the show around the original checklist created by Carmen Giménez for the Guggenheim’s presentation. However, some works were not able to travel to Houston, and we also had the opportunity to make some important additions to the show. Additionally, we felt that this project offered an ideal context to add some of Picasso’s important prints and drawings to the exhibition, and his graphic statements are the genesis of his first monochromatic exhibitions. While we obviously focused the checklist on works that range between hues of black, white, and gray, we made a couple exceptions for other key monochromatic works in Picasso’s career, including the great 1955 tapestry version of Guernica, which will be unique to Houston.

DDA: Alison and Enrique, please summarize why/how is the work of Picasso so integral to world/western/European artistic production?

ALG: No other artist has had a greater impact on the course of art in the Twentieth Century. Pablo Picasso was able to combine superb draftsmanship with an essentially structural imagination that allowed him to not only push the boundaries of representation, but also to engage the viewer’s passionate attention, whether he was working at his most abstract or returning to naturalism. He built his art on sources ranging from Paleolithic cave painting and African carvings to Spanish Old Masters, to contemporary film and photography–looking at the totality of Picasso’s career, you can see the history of world art measured through his eyes. And in turn, he revolutionized this history, making art that was purely contemporary and of the moment that he lived in. The fact that his career lasted so long, that he himself was so richly engaged with the world around him, and that he was possessed of a great personal charisma further added to his legendary status.

Enrique Mallén: Pablo Picasso was not only the most influential artist of the 20th Century, he also continues to have an important presence in the 21st Century art. As the critic, Jonathan Jones, points out, Picasso is the last artist you would expect our current century to admire. He was unapologetically selfish as an artist; he did not care if any other artist learned anything from him, and always preferred to be unique. Not surprisingly, he had no pupils to follow him, nor did he think about setting up an art academy, as numerous fellow artists did.

After Cubism, Picasso’s art–and art in general–would never be the same again. A 2006 exhibition organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art examined the fundamental role that Picasso played in the development of American art over the past century by juxtaposing his work with that of groundbreaking American artists. The lasting effect the Spanish painter had on artists living in an entirely different continent is amazing; but what is even more astounding is to note that many young artists of the 21st century still continue to register Picasso as a strong influence. Picasso exhibitions continue to draw immense crowds. Three of his paintings are on the list of highest prices paid in history.

DDA: Alison and Enrique, especially since Picasso is so well-known to the general art-viewing public for his “color” periods, e.g., blue and rose, how/why do the works in black and white illuminate Picasso’s work overall?

ALG: The “color periods” are names giving to very early stages of Picasso’s career by critics, not by the artist himself. Indeed, many works in both the so-called Blue and Rose periods come close to monochrome, as this exhibition demonstrates. When working on in paintings, he usually sketched in his compositions in black and white, adding color in the later stages. And in his sculptures, he frequently let the material, whether black iron or white plaster, define the color of the artwork. Later in his career he broke many sculptural conventions by painting his steel figures, such as the MFAH’s great Woman with Outstretched Arms, 1961, which is included in our show.

EM: Ranging from 1904 to 1971, the exhibition, Picasso Black and White, features 118 paintings, sculptures, and works on paper by Picasso. Thirty-eight of these works of art are appearing for the first time in the United States. The curator, who was the first director of the Museo Picasso in Málaga, presents a striking new interpretation of Picasso’s artistic vision. She writes, there are three aspects of the Spaniard’s style that come to light when we examine his works in black and white: 1) the relevance of Spanish heritage in his career; 2) the role cinema and news media play in his works; and 3) the importance of line over color in his production. Though he lived most of his life in France, Picasso never gave up his Spanish citizenship and remained very close to his family and friends that still resided in Spain. He was forced to remain in exile himself due to his opposition to the Franco regime. Perhaps for this reason, Picasso even went further in his emphasis of the Spanish themes as a counter-point to the Fascism that had taken root in his homeland. By hearkening back to earlier masters such as El Greco, Ribera, Zurbarán, Velázquez and Goya, whose “black-and-whites” were predominant, Picasso asserted that Spanish culture (through his own black-and-white creations) would eventually overcome the dictator.

The role of cinema and photography, the muted monochrome of these works (with some sepia and ochre tones occasionally blending in), serve as forceful reminders of the black-and-white movie news reels and half-tone newspaper photographs that shaped people’s consciousness throughout most of the 20th century. As the critic, Blake Gopnik, writes, even reproductions of the great masters came to Picasso’s generation mostly in black-and-white photographs, which the artist said he even preferred, and which may have led to the grays in his own interpretations of those masters.

In the greatest moments of Picasso’s career, the mostly monochrome tones of Analytic Cubism serve the important functional of breaking reality into its component parts and providing more precise information about it; Cubism’s photographic tones are meant to indicate this true dedication to “realism.” The restricted tones of Cubist painting can make them appear more like photographs viewed through a kaleidoscope than as an arbitrary combination of forms detached from reality. Viewers are expected to “read” these works as if they were a “written text”. Color, by contrast, reminded Picasso of the less significant, over-worked paintings of conservative painters. Monochrome works for him had the immediacy of drawings, which, like photographs, were able to project precise contours at that instant when light passes through a lens onto film. Picasso was after that kind of close contact with reality. Throughout his long career, Picasso used black-and-white to create masterworks of overpowering intensity. He also stated that color often weakens a composition. Interestingly, although Picasso is known by the general public for his Blue and Rose Periods, color has always been secondary to him. What really interested him was line and form, and for this reason, simple line drawings are frequently at the core of all his compositions, which are themselves often monochromatic. A limited palette allowed the Spaniard to explore his inventive formal experiments without the distraction of arbitrary color. He told his friend Edouard Teriade: “How many times, just as I was about to add some blue, did I notice that I didn’t have any! So I took some red and added it instead.” It could be for this reason that Picasso has not had a clearly identifiable “Black-and-White period,” along the lines of his Blue or Rose periods. Rather, as the photographer Brassai observed, he has had several intermittent points in his career when black-and-white clearly predominate: “A period of painting on a flat surface with a bright and varied palette was regularly followed by a sculptural period with little color.” Critics have argued that perhaps one possible motivation for these “colorless phases” harks back to the centuries-old tradition of grisaille, which often functions to create the illusion of sculpture, another one of Picasso’s true passions.

DDA: Enrique and Alison, please summarize the importance/effect of the black and white works in terms of the greater context of Picasso’s works.

EM: The exhibition cuts to the core of Picasso’s art as it touches on almost every major phase of the artist’s career. The works chosen span almost seventy years (from 1904 to 1971). However, while the selection covers most of Picasso’s career, it places more emphasis on three specific decades: most of the works date from the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s. As professor Michael Fitzgerald points out, this choice is indicative of a “transformative” procedure. It is precisely in these three decades that the artist resorts to black and white to focus on the creative process itself, the artistic practice that ultimately defines the structure of all works of art. Hence the paintings in the exhibition provide us an exceptional access to the artist’s conceptual development of the composition.

ALG: Picasso once stated: “I use the language of construction. The fact that in one of my paintings there is a certain spot of red isn’t the essential part of the painting. The painting was done independently of that. You could take the red away and there would always be the painting.” For Picasso, working in monochrome made it possible to focus on “the language of construction,” the fundamental touchstone of his creative imagination. He once explained that “color weakens,” and across his career he repeatedly stripped it from his major compositions. Picasso Black and White is the first exhibition to focus on this vital aspect of Picasso’s genius. As curator Carmen Giménez has observed: “This is a new way to see Picasso. When he paints in black and white, he goes to the essential. It shows how much you can do with little.”

Posted: May 19, 2013 at 3:16 am