Being Multifocal

Ser multifocal

Julian Baggini

Not so long ago, you could have described the job of science and philosophy as the pursuit of truth without anyone even raising an eyebrow. Now, many people believe that philosophy itself has shown that there is no such thing as truth, there are only a number of different perspectives. To think that some of these are better or truer is elitist, undemocratic, totalitarian.

There’s something attractive about the kind of democratic pluralism this view encourages. But it is ultimately unsustainable and no one wholeheartedly believes it. People’s commitment to the equal validity of all points of view soon evaporates if one such view turns out to include denial of the holocaust, young earth creationism or the existence of an intergalactic conspiracy of lizards. To allow someone the right to their opinion does not require conceding that their opinion is any good. Sometimes respecting a person’s right to believe what they do is really respecting their right to be crazy.

But there is something in the desire to allow different perspectives which is right. It’s not that there is no such thing as the truth, only different points of view. Rather, there are many points of view and it’s the totality of the true points of view which is the truth. To see as much of the whole truth as we can, we need to see as many truthful perspectives as we can.

A common metaphor that captures this idea is that we always look at things through a particular lens. Sometimes people take that to mean that we never see the world as it really is, we always see it distorted in some way. That’s the wrong way of cashing out the lens metaphor. A better way is to say that if we look through a lens and it’s a good one, we’ll bring something of the world into sharp focus and make it clear. But almost invariably that comes at the expense of other things that are either completely out of the frame or blurred.

So, when we look at the world through the lens of say, sex or gender, you’ll see all sorts of real differences between populations of men and women. You’re only being misled by this if you take this to be the complete picture and ignore everything else that is out of the frame or blurred. Switch lens and look through the glass of material wealth, and you find that almost everything in life – from educational achievement to health and longevity to choice of mate – is affected by your position on the economic ladder. And indeed it is, but it would be equally mistaken to think that this is the only or key factor in explaining human behaviour, because you’re missing all the things you would see if you were looking through a different lens.

Genetics provides another such lens. Genes have an influence on so much, from who we vote for to whether we believe in God, that it can easily appear to be the key to human understanding. You can see how far we have bought into this by the fact that if identical twins both develop, say, breast cancer, people react as though that is only to be expected. If oonly one does so, people react as though this is an anomaly that needs explaining.

Culture is a fourth lens, and I think one reason why the rather tedious nature v nurture debate rumbled on so long was that different researchers were seeing so clearly how important the one they were looking at was that they just couldn’t conceive that they were only seeing one part of the picture.

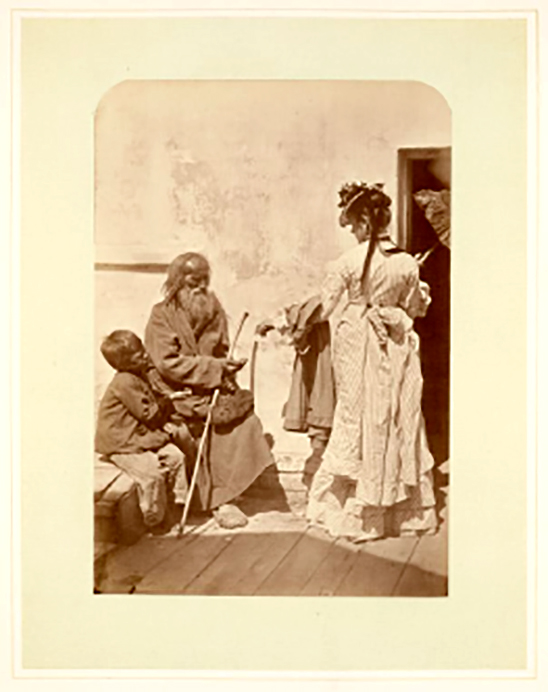

The general principle is that it’s only when you have a whole variety of lenses and you avail yourself of all that they can capture that you can see the fuller truth of a situation. Take as an example this picture of a Victorian woman giving alms to a poor person in what looks like India.

Depending on which lens you look through you might see this image as depicting the superior compassion and philanthropy of the female sex (gender lens), the socio-economic division in society and the principle of noblesse oblige (class), a snapshot of a moment in time when the white imperialists lorded it over the indigenous Indian population (history), the details of circumstances which effect whether people choose to be generous rather than not (social psychology), an example of how a certain behaviour – altruism – resulted from tit-for-tat co-operation (evolutionary psychology), how Christian women follow Jesus’s teaching and give to the poor (beliefs), how behaviours reflect character (Aristotelian virtue ethics) or personality (developmental psychology).

Each of these lenses gives you just one aspect of the truth. You don’t have to choose which one reveals the real nature of the situation, and no one by itself can give you the accurate picture. You need to avail yourself of all of them.

Spelled out, the principle seems so clear as to be obvious. And yet in practice we often neglect it. For example, think about how we interpret studies which show differences between the sexes. A few years ago, I conducted an online survey asking people what they complained about. I then looked to see if the sex of the respondents made a difference. It did. The men complained mainly about ineffective politicians, poor service and public transport. Women tended to complain more about the cost of living, spouses, partners and friends, and the weather. They also complained a lot less about television.

To take another example, a former colleague has run an online thought experiment where people are asked questions about a very specifically described situation. There were asked whether, in the exact case described, it was “morally wrong to have sex if the partner will come to regret it” or “morally wrong to have sex if the partner is intoxicated, albeit cogent, and would not have had sex otherwise”. 57% of men thought sex would be immoral in the first case, 71% in the second, compared to 68% and 80% of women respectively. With the high numbers of people taking part, this was a highly significant statistical difference.

Studies like these seem to be very straightforward. They tell us about real sex differences, leading many to conclude that boys will be boys and girls will be girls. Lots of people object to these studies but the answer come back: I’m sorry, you can’t just reject findings because you don’t like or ones you ideologically object to. Facts are facts, data are data, and you’ve just got to live with them.

Of course, there are still enough flawed studies and dodgy data out there to be wary. But the real problem with such studies is not that they say anything false. The problem is that they only look at one part of a much broader picture and if you can’t see how the part fits into the whole you may as well be squinting at it, no matter how clear that part appears to you.

Take the complaint study. Look through the sex lens and you see a very clear difference. But there were other lenses we could have used and one of these was culture. If you compare people according to whether they were American or British you also see very large differences. What’s more, these differences were greater than the sex ones, so whereas on average there was around a 9% difference in the responses of men and women, and a 13% difference between the responses of Americans and Britons.

This puts the gender differences in an important context. When I looked at this data more carefully, it emerged that the complaint pattern of an American woman was closer to that of an American man than to that of a British woman. So for all the reality and importance of sex differences, culture turns out to be much more important. Clearly it would only repeat the mistake to now say that culture explains it all. The moral is not that we keep looking for the biggest determinant of difference and name that as the real one, discarding the rest. It is rather that the picture is extremely complicated and there are many factors at play, which all interact.

If we return to the second study, now sensitive to the distorting nature of only looking through one lens, you don’t need to even switch lenses to see that the findings are perhaps not quite so impressive as they first seem. You need to simply avoid the trap of placing too much emphasis on the one aspect of reality which just happens to be in sharp focus. And so you look at the data again and see, for all the real differences they show, it remains the case that nine times out of ten, men and women are as likely to give the same answer as not. In the second case, for example, 71% of men and women agreed it was morally wrong, while 20% of men and women thought it wasn’t. That only leaves 9% of men and women who disagreed. So instead of a striking example of how different men and women are, it could equally be seen as an even more striking demonstration of how often they see the world in the same way.

Taking this multifocal perspective is particularly important when it comes to ourselves. We need to recognise that we are multiplicities, and just as there are many lenses for bringing different features of the world into focus, so there are different lenses for bringing different aspects of ourselves into focus.

To switch metaphor here, we might think of mirrors rather than lenses. In the nationhood mirror I see an Anglo-Italian, in the worldview mirror I see a sceptical humanist, in the political mirror I see a kind of social democrat, in the relationship mirror I see a life partner, in the gender mirror a man, in one psychological type mirror an introvert, professionally I see a writer and thinker, in the pleasures mirror I see an eater. All of these things say something about who I am and I do not need to decide which of these identities captures my “real self” and which are merely roles I play, masks I put on. My real self is the totality of all these things.

This way of thinking gives us more resilience. When we think of ourselves just in terms of a few core identities, change can threaten our very sense of self: doubts about our beliefs, a change in our relationship status, a loss of job: all these things can pose an unnecessarily deep existential threat to those who place too much importance on just one aspect of who they are.

This also matters politically. In Identity and Violence, Amrtya Sen argued persuasively that when we come to see ourselves and others too much in terms of just one or two core identities, particularly those of nationhood or religion, we sow the seeds of social division. The greatest hope for humanity and peace is that we come to see ourselves and others in more plural terms.

When it comes to ourselves and the world, however, we must not lose sight of the fact that we cannot simply decide what we want to see. We must use true lenses, true mirrors, to piece together a realistic picture of the world. You can no more be whatever what you want to be than the truth can be whatever you want it to be. But by paying more attention to the many things you could be and in some sense already are, you can widen the horizons of your own possibilities.

Julian Baggini is a British philosopher and the author of several books about philosophy written for a general audience. He is the author of The Pig that Wants to be Eaten and 99 other thought experiments (2005) and is co-founder and editor of The Philosophers’ Magazine. He was awarded his Ph.D. in 1996 from University College London for a thesis on the philosophy of personal identity. In addition to his popular philosophy books, Baggini contributes to The Guardian, The Independent, The Observer, and the BBC. Twitter: @microphilosophy

Julian Baggini is a British philosopher and the author of several books about philosophy written for a general audience. He is the author of The Pig that Wants to be Eaten and 99 other thought experiments (2005) and is co-founder and editor of The Philosophers’ Magazine. He was awarded his Ph.D. in 1996 from University College London for a thesis on the philosophy of personal identity. In addition to his popular philosophy books, Baggini contributes to The Guardian, The Independent, The Observer, and the BBC. Twitter: @microphilosophy

Hasta hace poco se hubiera podido afirmar que la misión de la ciencia y la filosofía era la de buscar la verdad sin que ello causara asombro. En la actualidad muchas personas creen que la filosofía ha demostrado que no existe el concepto de “verdad”, sólo diferentes perspectivas. Pensar que algunas de éstas son mejores o más verdaderas es elitista, poco democrático y totalitario.

Hay algo muy atractivo en el pluralismo democrático que esta idea promueve. Aunque es insostenible y, sinceramente, nadie lo cree. El compromiso de la gente con respecto a la validación equitativa de todos los puntos de vista se evapora rápidamente si una de las perspectivas acaba por negar el Holocausto, el creacionismo o la existencia de una conspiración intergaláctica de lagartijas. Reconocer el derecho de alguien a opinar no significa conceder que dicha opinión sea buena. A veces, respetar el derecho de cada persona a creer lo que sea es similar a respetar su derecho a estar locos.

Pero hay algo muy sensato en el deseo de permitir la coexistencia de diversas perspectivas. No es que no exista un concepto como “la verdad” sino sólo diferentes puntos de vista. Hay distintas perspectivas y es la totalidad de ellas la que conforman “la verdad”. Para poder acceder a la verdad en su conjunto necesitamos considerar la mayor cantidad posible de puntos de vista verdaderos y a nuestro alcance.

Una metáfora común que captura esta idea es la de mirar las cosas a través de un cristal particular. En ocasiones la gente interpreta ese símil como la imposibilidad de percibir el mundo tal y como es ya que siempre lo captamos distorsionado. Este es un modo erróneo de interpretar dicha metáfora, sin duda. Un mejor camino sería decir que si el lente a través del cual observamos el mundo es bueno, enfocamos algo de tal modo que conseguimos aclararlo. Aunque esto sucede, invariablemente, a expensas de otras cosas fuera de nuestro alcance o que resultan borrosas.

Cuando vemos al mundo a través de una perspectiva de género, por poner un ejemplo, podremos ver todo tipo de diferencias reales entre hombres y mujeres. Pero si tomamos esas diferencias como si constituyeran el panorama completo e ignoramos todo lo demás —aquello que se ve borroso o fuera de foco—, estaríamos equivocados. Si cambiamos de lente y observamos a través del cristal de las cosas materiales encontraremos que casi todo en la vida —desde los logros en educación, salud y longevidad hasta la elección de pareja— se ve afectado por nuestra posición en la escala económica. Y en efecto, así es, aunque sería igualmente erróneo pensar que esta es la única clave para explicar el comportamiento humano porque estaríamos omitiendo aquello que percibiríamos si usamos otro lente.

La genética nos proporciona una perspectiva distinta. Los genes determinan tantas cosas —desde por quién votamos hasta si creemos en Dios— que fácilmente podrían considerarse como la clave para el entendimiento humano. Se puede observar hasta qué punto creemos esto si tratándose de un par de gemelas obviamente idénticas, por ejemplo, consideramos si ambas desarrollarán cáncer de mama o no. En caso de que sólo una de ellas lo hiciera, la gente reaccionaría como si fuese una anomalía que necesita explicación.

La cultura es otro cristal a través del cual contemplamos el mundo. Una de las razones por las cuales el más bien tedioso debate en torno de la naturaleza versus la educación duró tanto tiempo fue porque los investigadores involucrados estaban tan convencidos sobre la importancia de lo que observaban que, por lo mismo, parecía difícil concebir que sólo estaban viendo una parte del todo.

El principio general es que es sólo cuando contamos con una variedad de perspectivas amplia y, a su vez, somos capaces de servirnos de todo lo que ellas pueden capturar, se puede obtener una verdad más íntegra de la situación. Tomemos como ejemplo el cuadro de una mujer victoriana dando limosna a un pobre en lo que parece la India.

Dependiendo del cristal con que se mire esa imagen podría representar la superioridad compasiva y filantrópica del sexo femenino (un lente de género), la estratificación socioeconómica de una sociedad y el principio de nobleza obliga (clase), una instantánea de cuando los imperialistas blancos dominaban a la población indígena (historia), los detalles de ciertas circunstancias en las cuales las personas optan por ser generosos en lugar de no serlo (psicología social), un ejemplo de cómo determinado comportamiento –el altruismo– es resultado de la cooperación (psicología evolutiva), cómo las mujeres cristianas siguen las enseñanzas de Jesús ayudando a los pobres (creencias), cómo el comportamiento refleja la personalidad (virtudes éticas aristotélicas) o la personalidad (psicología evolutiva).

Cada uno de estos cristales proporcionan sólo un aspecto de la verdad. No es necesario elegir cuál de ellos revela la naturaleza real de la situación y nadie por sí solo puede darnos la imagen correcta. Es necesario valernos de todos.

Una vez detallado el principio todo parece tan claro que resulta obvio. Y aún así, lo negamos. Pensemos por ejemplo en cómo interpretamos los estudios que muestran las diferencias entre los sexos. Hace algunos años dirigí una encuesta en línea en donde se interrogaba a la gente sobre aquello que les disgustaba. Después analicé si sus respuestas estaban determinadas por el género de los participantes y, en efecto, los hombres se lamentaban sobre todo de la poca efectividad de los políticos, los malos servicios y del transporte público; las mujeres, por su parte, tendían a quejarse más del costo de la vida, de sus esposos o parejas, de los amigos y del clima –y casi nunca se quejaban de la televisión.

Otro ejemplo: un antiguo compañero realizó un experimento en el que se cuestionaba sobre una situación específica. Se preguntó a la gente si, en una situación descrita para el caso, era “moralmente malo tener sexo si la pareja podría llegar a lamentarlo” o si “era moralmente malo tener sexo con una pareja que estuviera intoxicado y que, de otro modo, no tendría sexo”. 57% de los hombres contestaron que sería inmoral tener sexo en el primer caso, 71% en el segundo, comparado con las mujeres que respondieron con el 68% y el 80%, respectivamente. Teniendo en cuenta el número considerable de gente que participó, este fue un resultado significativamente importante en cuanto a la diferencia entre las estadísticas.

Estudios como este parecen muy sencillos. Nos hablan de diferencias reales entre los sexos, llevando a muchos a concluir que los hombres siempre pensarán como hombres y las mujeres como mujeres. Mucha gente rechaza tales estudios aunque la réplica que reciben siempre es la misma: “Lo siento, no puedes negar los descubrimientos porque no te gustan o porque ideológicamente los rechazas. Los hechos son los hechos, la información es la información y no queda más que aceptarlos”

Claro, existen estudios poco serios con información dudosa de la cual debemos cuidarnos. Pero el verdadero problema con este tipo de estudios no es que proporcionen datos falsos. El problema es que sólo consideran una parte del panorama y si uno no alcanza a advertir cómo la parte encaja en el todo podemos extraviarnos y será imposible ver nada por más claro que aparezca.

Retomemos el ejemplo de mi encuesta. Veamos a través del lente del género y advertiremos diferencias bastante claras, aunque había otros puntos de vista que pudimos haber utilizado. Uno de ellos es el de la cultura. Si se compara a las personas de acuerdo con su origen, es decir, americanos o ingleses, podemos observar también grandes contrastes. Más aún, esas discrepancias resultaron más profundas que las de género. En ese sentido, donde la divergencia entre las respuestas de los hombres y las mujeres fue del 9% en promedio, entre los americanos e ingleses tal diferencia se elevó al 13%.

Esto coloca a las disimilitudes de género en un contexto importante. Cuando analicé la información con más detalle fue evidente que el patrón de quejas de una mujer americana era más parecido al de un hombre americano que al de una mujer inglesa. Así que, en la cultura, la realidad y la relevancia de las diferencias entre los sexos acaban siendo mucho más importantes. Desde luego, recaeríamos en un error si se afirmara ahora que la cultura lo explica todo. La moraleja no es que sigamos buscando el factor determinante entre las diferencias así como su nombre verdadero descartando el resto. La realidad es que la totalidad es extremadamente complicada y existen muchos factores en juego que interactúan entre sí.

Si retomamos el segundo ejemplo, más sensibilizados ya ante la natural distorsión de la realidad bajo un solo enfoque, no hay necesidad de cambiar de lente para advertir que los resultados no son tan impresionantes como parecían en un principio. Es necesario evitar la tentación de poner demasiado énfasis en un aspecto de la realidad, por más definitivo que aparezca. Y si volvemos a observar la información una y otra vez, con todas las diferencias reales que muestran, lo cierto es que en 9 de cada 10 casos los hombres y las mujeres son más propensos a dar las misma respuestas. En el segundo estudio, en efecto, 71% de hombres y mujeres coincidieron en que era moralmente malo mientras que el 20% de los hombres y mujeres pensaron que no. Eso nos deja un 9% de hombres y mujeres que estuvieron en desacuerdo. En ese sentido, en lugar del llamativo ejemplo de cuán diferentes son los hombres de las mujeres, podría verse también como la prueba aún más llamativa de cuán reiteradamente perciben el mundo de la misma forma.

Tomar esta perspectiva multifocal es particularmente importante cuando se trata de nosotros. Debemos reconocer que somos multiplicidades y así como hay muchos cristales a través de los cuales ver las diferentes características del mundo los hay también para ver nuestros diversos aspectos personales.

Para cambiar de metáfora podríamos recurrir a espejos en lugar de cristales. En el espejo de una nación veo a un inglés-italiano, en el del mundo contemplo a un ser humano escéptico, en el político veo una especie de social-demócrata, en el de las relaciones veo a una pareja de por vida, en el del género a un hombre, en el psicológico a un introvertido, profesionalmente veo a un escritor y pensador, en el espejo de los placeres veo a un glotón. Todas estas características dicen algo sobre quien soy y no necesito decidir cuál de esas identidades capturan mi ser verdadero y cuáles son únicamente los papeles que represento, máscaras que me pongo. Mi verdadero ser es la totalidad de todas estas cosas.

Esta forma de pensamiento nos da elasticidad. Cuando nos concebimos sólo en términos de algunas identidades básicas, el cambio puede ser amenazante para nuestro sentido de identidad: dudas sobre nuestras creencias, cambio en nuestras relaciones, la posibilidad de perder un trabajo: todas estas cosas pueden representar una profunda amenaza existencial para aquellos que ponen demasiada importancia en un solo aspecto de su ser.

Esto también es políticamente relevante. En su libro Identidad y violencia, Amrtya Sen señala que cuando concebimos a los otros y a nosotros mismos en términos de una o dos identidades radicales, particularmente aquellas de nacionalidad o religión, sembramos las semillas de la discordia social. La mayor esperanza de paz para la humanidad es que podamos vernos a nosotros y a los otros en términos más plurales.

Sin embargo, cuando se trata de nosotros y del mundo no debemos perder de vista el hecho de que no podemos decidir aquello que queremos ver. Debemos usar lentes y espejos certeros para reconstituir una imagen realista del mundo. Uno no puede ser lo que no es por más que lo anhelemos así como la verdad no puede ser lo que uno quiera. Aunque al brindar mayor atención a la variedad de posibilidades que uno puede ser –y hasta cierto punto ya es–, ampliamos nuestro horizonte de posibilidades.

Julian Baggini. Filósofo británico autor de The Pig that Wants to be Eaten and 99 other thought experiments (2005), cofundador y editor de The Philosophers’ Magazine. Además de sus libros de filosofía, Baggini colabora habitualmente en The Guardian, The Independent, The Observer y la BBC.Twitter: @microphilosophy

Julian Baggini. Filósofo británico autor de The Pig that Wants to be Eaten and 99 other thought experiments (2005), cofundador y editor de The Philosophers’ Magazine. Además de sus libros de filosofía, Baggini colabora habitualmente en The Guardian, The Independent, The Observer y la BBC.Twitter: @microphilosophy