Can President Trump Save the Coal Industry?

¿Puede el presidente Trump salvar la industria del carbón?

Hélène Dieck

On the first day of June 2017, Donald Trump stood in the Rose Garden to announce his decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord. This agreement strives to limit global temperature rising this century to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Along with financial contributions, this agreement requires all signatories to report regularly on their emissions as well as their efforts to implement measures to limit climate change.

This accord was signed in December 2015 by all countries in the world with the exception of Nicaragua and Syria. Nicaraguan representatives refused to take part in the agreement as they felt the accord did not go far enough in the conditions it imposed on developed countries. In September 2017, however, President Daniel Ortega announced that he would sign, leaving the United States and Syria as the only two countries in the world that are not part of the agreement. Despite President Trump’s intention to leave the Paris Climate Accord, article 28 of the Accord prevents the United States from effectively withdrawing before November 2020.

In his speech announcing his decision last June, President Trump cited several arguments that would appeal to his Republican base, including having to spend billions on reducing pollution and protecting jobs in the U.S., particularly in the coal industry. To the average American republican voter, these issues are usually more salient than concerns with climate change. However, recent data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) tends to show that on the contrary, this decision would in fact create even more unemployment. Indeed, only 65,971 individuals worked in coalmines in 2016 while according to the non-profit Solar Foundation, 260,077 individuals were employed by the solar industry in the United States.

In addition to repealing the Paris Accord Agreement, Scott Pruitt, Administrator of the Environment Protection Agency and Trump’s appointee, recently passed a measure that would effectively dismantle the Clean Power Plan that was passed in 2015 under the Obama administration. This action would remove environmental regulations on coal power plants, thus further supporting the coal industry at the expense of public health. The announcement of this repeal was symbolically made in front of a group of coal miners at an event in Kentucky in early October.

What does this mean for the future of energy in the United States? Will coal miners really be getting back to work? Four days after the Pruitt’s speech, Vistra Energy Corporation announced that it would shut down two coal power plants in Texas. This is just the latest in a string of coal power plant closures driven not by regulation, but by economics. According to the Sierra Club, 262 coal plants have retired or are in the process of retiring, leaving 261 plants remaining.

Yet given this overwhelming government support, will we see a resurgence in coal? Most experts agree that regardless of regulatory changes, the demise of coal is a question of when and not if. The United States has experienced a gas renaissance thanks to cheap and plentiful shale gas, which has spawned an LNG export surge with companies such as Cheniere Energy investing billions. In fact, simple economics have more to do with coal’s demise than any government policy. Cheap and abundant natural gas has been the largest catalyst to the death-spiral of coal power production. According to EIA data, coal generated nearly 30 percent of U.S. electric power in 2016, down from 50 percent in the earlier 2000s. Despite this data, the EIA, which consistently under-forecasted renewable energy production, now suddenly projects an increase in coal consumption in the coming years.

The second reason for the drop in coal production is associated with the drop in renewable energy costs. Based on the most recent analysis of Lazard, an investment bank, wind energy costs have dropped 66 percent in the last seven years while solar Photovoltaic (PV) costs have decreased 85 percent, resulting in a cost already lower than coal’s. Additional price drops are expected throughout the coming decades as additional production leads to further economies of scale. Bloomberg expects solar PV costs to drop an additional 66 percent by 2040. Onshore and offshore wind energy prices are also expected to drop significantly with the former expected to fall 47 percent and the latter, an astonishing 71 percent by 2040. Bloomberg further estimates that by 2030, new wind and solar PV will undercut existing coal plants operational costs in some countries around the world. To complement the intermittency of renewables, the United States would require traditional energy plants including gas and nuclear, complemented by energy storage such as pumped hydro and batteries. Battery energy storage costs are, like renewable energy, dropping exponentially in price, with Li-ion battery cost dropping from $1,000 / kwh in 2010 to $273 / kwh in 2016 and are expected to drop another 73 percent by 2040.

If these arguments were not enough to drive support for solar and wind power supply, the Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health recently published research that air pollution is the highest cause of premature deaths, causing over 6.5 million fatalities in 2015. So, if solar and wind power provide more jobs, are better for the environment and are more profitable, why is the current administration pushing coal and not embracing renewable energy? During the presidential campaign, the Republican candidate vowed to support the coal mining industry and has continued to push this policy since entering the White House; yet at what point will market factors come into play? Given the recent proposal of Energy Secretary Rick Perry to subsidize coal power plants, it appears that the administration will do whatever it takes to prop up this dying industry.

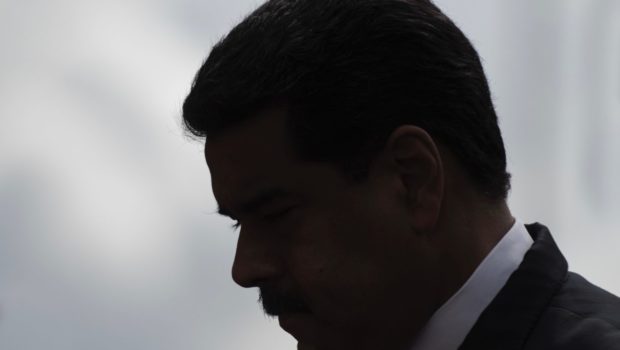

*Cover image by Joao Martinho

Hélène Dieck received her PhD from Sciences Po, Paris, France. She was previously responsible for elaborating military doctrine at the French Ministry of Defense and served as a visiting researcher at the RAND Corporation, Washington, DC. She currently works as a migrant welfare specialist at Qatar Foundation and recently publishedThe Influence of Public Opinion on Post Cold War U.S. Military Interventions (Palgrave, 2015).

Hélène Dieck received her PhD from Sciences Po, Paris, France. She was previously responsible for elaborating military doctrine at the French Ministry of Defense and served as a visiting researcher at the RAND Corporation, Washington, DC. She currently works as a migrant welfare specialist at Qatar Foundation and recently publishedThe Influence of Public Opinion on Post Cold War U.S. Military Interventions (Palgrave, 2015).

©LiteralPublishing

Traducción de Rose Mary Salum

El primer día de junio de 2017, Donald Trump se paró en el Jardín de las Rosas para anunciar su decisión de retirarse del Acuerdo Climático de París. Este acuerdo se esfuerza por limitar el calentamiento global que en este siglo ha aumentado 2 grados Celsius por encima de los niveles preindustriales. Junto con las contribuciones financieras, este acuerdo requiere que todos los miembros informen regularmente sobre sus emisiones, así como sus esfuerzos para implementar medidas para limitar el cambio climático.

Este acuerdo fue firmado en diciembre de 2015 por todos los países del mundo, con la excepción de Nicaragua y Siria. Los representantes nicaragüenses se negaron a tomar parte en el acuerdo, ya que consideraban que éste no era lo suficientemente firme en las condiciones que imponía a los países desarrollados. Sin embargo, en septiembre de 2017, el presidente Daniel Ortega anunció que firmaría el tratado, dejando a los Estados Unidos y a Siria como los únicos dos países en el mundo que no forman parte del acuerdo. A pesar de la intención del presidente Trump de abandonar el Acuerdo Climático de París, el artículo 28 del tratado impide que Estados Unidos se retire efectivamente antes de noviembre de 2020.

En su discurso anunciando su decisión el pasado mes de junio, el presidente Trump citó varios argumentos que convencerían a sus seguidores republicanos de apoyar su decisión y que incluyen el gasto de miles de millones de dólares en reducir la contaminación y proteger el tema del empleo en los EE. UU., Particularmente en la industria del carbón. Para el votante republicano estadounidense promedio, estos temas suelen ser más importantes que las preocupaciones del cambio climático. Sin embargo, los datos recientes de la Administración de Información de Energía de los EE. UU. (EIA) tienden a mostrar que, por el contrario, esta decisión crearía aún más desempleo. De hecho, solo 65.971 personas trabajaron en minas de carbón en 2016, mientras que según la Fundación Solar sin fines de lucro, 260.077 personas fueron contratadas por la industria solar en los Estados Unidos.

Además de revocar el Acuerdo de París, Scott Pruitt, Administrador de la Agencia de Protección Ambiental designado por Trump, aprobó recientemente una medida que efectivamente desmantelaría el Plan de Energía Limpia que se aprobó en 2015 bajo la administración de Obama. Esta acción eliminaría las regulaciones ambientales sobre las centrales eléctricas de carbón, apoyando así la industria del carbón a expensas de la salud pública. El anuncio de esta derogación se realizó simbólicamente frente a un grupo de mineros del carbón en un evento en Kentucky a principios de octubre.

¿Qué significa esto para el futuro de la energía en los Estados Unidos? ¿Realmente los mineros del carbón volverán a recuperar su trabajo? Cuatro días después del discurso de Pruitt, Vistra Energy Corporation anunció que cerraría dos plantas de carbón en Texas. Esto ha sido provocado, no tanto por la regulación, sino por la economía. Según el Sierra Club, 262 plantas de carbón se han retirado o están en proceso de salirse del mercado, dejando 261 plantas restantes.

Dado el abrumador apoyo del gobierno, ¿veremos un resurgimiento del carbón? La mayoría de los expertos coinciden en que, independientemente de los cambios regulatorios, la desaparición del carbón es una cuestión de tiempo. Los Estados Unidos han experimentado un renacimiento del gas gracias a su abundancia y precio. Esto ha engendrado un aumento de las exportaciones de gas natural con compañías como Cheniere Energy que han invertido miles de millones de dólares. De hecho, la economía simple tiene más que ver con la desaparición del carbón que con cualquier política gubernamental. El gas natural barato y abundante ha sido el factor definitivo para que el uso del carbón desaparezca. De acuerdo con los datos de EIA, el carbón generó casi el 30 por ciento de la energía eléctrica de los EE. UU. En 2016, un 50% menos que en los primeros años del 2000. A pesar de estos datos, el EIA, que sistemáticamente subestimó la producción de energía renovable, ahora proyecta repentinamente un aumento en el consumo de carbón en los próximos años.

La segunda razón por la cual la producción del carbón ha disminuido se asocia con la caída en los costos de energía renovable. Según el análisis más reciente de Lazard, un banco de inversión, los costos de la energía eólica han disminuido un 66% en los últimos siete años, mientras que los costos de la energía solar fotovoltaica han descendido un 85 %, lo que resulta en un costo menor que el del carbón. Se esperan caídas de precios adicionales a lo largo de las próximas décadas, ya que la producción adicional conduce a nuevas economías de escala. Bloomberg espera que los costos de la energía solar caigan otro 66% más para 2040. También se espera que los precios de la energía eólica terrestre y marítima caigan significativamente; el primero espera que baje un 47% y el último, un asombroso 71 % para el 2040. Bloomberg estima además que 2030, la nueva energía eólica y solar reducirá los costos operacionales de las plantas de carbón existentes en algunos países del mundo. Para complementar la intermitencia de las energías renovables, los Estados Unidos requerirían plantas de energía tradicionales, incluidas las de gas y nucleares, complementadas con el almacenamiento de energía, como las centrales hidroeléctricas y las baterías. Los costos de almacenamiento de energía de la batería son, como la energía renovable, cayendo exponencialmente en precio, con el costo de la batería de iones de litio de $ 1,000 / kwh en 2010 a $ 273 / kwh en 2016 y se espera que caiga otro 73% para 2040.

Por si estos argumentos no fueran suficientes para impulsar el suministro de energía solar y eólica, la Comisión Lancet sobre Contaminación y Salud publicó recientemente investigaciones sobre la contaminación del aire como la causa más alta de muertes prematuras, causando más de 6,5 millones de decesos en 2015. Por lo tanto, si la energía solar y la energía eólica proporciona más empleos—además de que es mejor para el medio ambiente y es más rentable—, ¿por qué la administración actual está presionando para imponer la energía del carbón y no adoptando la energía renovable? Durante la campaña presidencial, el candidato republicano prometió apoyar a la industria minera del carbón y ha seguido impulsando esta política desde que ingresó a la Casa Blanca; sin embargo, ¿en qué punto entran en juego los factores del mercado? Dada la reciente propuesta del Secretario de Energía, Rick Perry, de subsidiar las plantas de energía a carbón, parece que la administración actual hará lo que sea necesario para que esta industria moribunda repunte.

Helene Dieck escritora y periodista. Ha sido la responsable de elaborar la doctrina militar de Ministerio de Defensa Francés e investigadora visitante del RAND Corporation, Washington, DC. Actualmente trabaja en el Qatar Foundation. Su libro se titula The Influence of Public Opinion on Post Cold War U.S. Military Interventions (Palgrave, 2015).

Helene Dieck escritora y periodista. Ha sido la responsable de elaborar la doctrina militar de Ministerio de Defensa Francés e investigadora visitante del RAND Corporation, Washington, DC. Actualmente trabaja en el Qatar Foundation. Su libro se titula The Influence of Public Opinion on Post Cold War U.S. Military Interventions (Palgrave, 2015).

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.