Where The Pain is Inhuman

Donde el dolor no es humano

Dainerys Machado Vento

Translated by Victor Gonzalez

I was on a visit to Cuba in May 2018, when the Cubana de Aviación airliner that services the Havana – Holguin route crashed to the ground shortly after takeoff, leaving more than 100 dead and a sole survivor. I remember my fear of having to fly in an airplane just a few days later to leave the county, my need to consider the statistics: if something so terrible had just happened, there was little chance it would happen again. I remember the commotion, people sharing the most horrific videos of the crash from cell phone to cell phone. But above all, I remember the Cuban press coverage of the event. In front of every father and mother mourning a son, in front of every daughter mourning a mother, there was a Cuban journalist from an official outlet asking, “What do you have to say to the government? What do you thank the revolution for?” The answers, of course, were not always as expected. It’s more difficult for people who are mourning to keep up political and ideological appearances. We’re more visceral in times of suffering; we often say things we’d never say in better times. Masks fall off when we have nothing left to lose, or after losing a son, a mother, or a brother. Especially when all hope is lost. Over several days of watching the disaster coverage, I learned that something in Cuba was irremediably broken. To turn a humanitarian tragedy into political fodder, a media circus of gratitude for the revolution and its government was, to say the least, a grotesque act.

In my country, it’s been a long time since the pain stopped being human and started becoming political. This was confirmed on Sunday, July 11, 2021, when thousands of people took to the streets in more than 60 cities to express their discontent. But police silenced them with their nightsticks, following direct orders from the president of the Republic, Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, that “revolutionaries” take to the streets. “The order has been given,” he said, pounding the words with his hands onto the table of history. Nobody told me this, I saw it. Nobody paid me to see it. On the contrary, Cubans around the world have carefully watched these unprecedented times in our country’s recent history. We have watched with astonishment and pain, with uncertainty, and with the still looming fear—“best to not get involved”—that has been inoculated in all of us our entire lives.

Nearly two weeks after these events, Cuba continues to politicize the pain that caused so many people to take to the streets with demands for medicine and better living conditions. This is because the people who went out to march on July 11 shouted ‘liberty’, which easily translates to free and democratic elections every four or six years, or a plurality of political parties, or social and economic mobility. But people were also in the streets—at least in Palma Soriano, where one of the largest demonstrations (the second to receive news coverage) took place—because they’d had no electricity since 6:00 a.m.

I won’t talk about the deplorable economic and spiritual disillusionment that has suffocated Cuba for decades, or the marked difference that divides the population who are able to receive some form of remittance from those who have no external support and have to wait several hours in line for food, who invent ways to survive each day and ask neighbors for old bread. I will not talk about the country that says, “if you don’t like it, go away,” as if you hadn’t been born there and didn’t carry it inside you, as if your friends’ and families’ pain on the island did not hurt you. I have spoken on the subject many times in recent years. And, fortunately, people whose vision I greatly admire have analyzed the root causes of the demonstrations and have shared very valuable testimonies about the subsequent repression. The words of Cuban academic Odette Casamayor in Literal, published in the heat of the moment, speak of inequality and the loss of utopias. The writer Abilio Estevez analyzes, from his personal experience, the complexity of what happened in “Vengo de vivir entre los bárbaros.” Playwright Norge Espinosa has written, from his home in Havana, “Cuba, entre el límite y la frontera”, a look at the need for reconciliation in the country of hopelessness. Meanwhile, independent journalists in El Toque are providing regular coverage of the demonstrations, broadcasting only news they are able to verify beforehand. They’re also analyzing the legality and/or illegality of everything that has happened to demonstrators after the protests. Although no official figures exist, it is estimated that more than 500 people were still imprisoned or arbitrarily detained while I was writing this article. In other words: more than 500 people disappeared after the protests. Among them are at least nine minors.

On July 14, Alejandro Hernandez published the enlightening text “Fiesta y velorio en La Habana” in Infobae, where he presents Cuba as “a society where the disconnection between the reality of the street and the official propaganda was, and continues to be, increasingly abysmal.” In English, Ruaridh Nicoll has written for The Spectator, The Guardian and other European media outlets with the privileged eye of a foreigner who loves Cuba but is amazed to see its people lose their fear. Actor and playwright Yunior Garcia has also spoken and written from the inside on behalf of the people who have been putting their bodies on the line since November 2020, to publicly show their disagreement with how the Cuban government treats artists, intellectuals, and dissidents. García is one of the most visible members of the 27N movement. And I don’t want to repeat ideas when so many talented and brave people have raised their voices with firmness and clarity, with understanding and a desire for change.

I do have questions. A lot of questions. Some are for those who deny there is need for change in Cuba. Others are for the Cuban government, though it’s highly unlikely they’d listen to me, the same way they don’t listen to the people living on the island. These questions arrive amid the same overwhelming feeling of chaos over the past few days. I believe that in Cuba, just like anywhere else in the world, pain should also be human.

Why is it that when we grew up in Cuba hearing that the revolution was made by the poor, for the poor, the poor are now being called marginal, or “that sector”, or a mistake of the revolution? In Cuba, there are no private or religious schools. Every being that walks on that island has had a public, state and socialist education. Every “marginal” person that inhabits the country is the product of 60 years of education that has been not only revolutionary, but doctrinarian. Why call those who go out to protest delinquents, or marginal? Wasn’t what they call revolution by them and for them? Shouldn’t any political system that claims to be not socialist, but leftist, have a humanistic vocation?

The Cuban government has stated on official television that the CIA and the Cuban-American mafia are orchestrating another attempt to destabilize the country. This is a story that has been repeated many, many times. The truth is that the country seems quite destabilized. Schools and universities have not been able to reopen during the pandemic, and the health system has collapsed in several cities due to the increase of covid cases, which has come in several waves, as in most countries around the world. On national television, it has been stated that some of these U.S. groups have blackmailed Cubans into protesting and creating a narrative of police repression on social networks. The proposed payment was ostensibly one or two cell phone refills. That’s right, according to them, the political opposition is being paid off with refills. If this were true, what conditions do thousands of people in Cuba live in that would cause them to go out to protest against the government in exchange for a cell refill—the equivalent to 20 dollars, and with a one-month expiration date?

Why does a political process that began as a revolution and has since turned into an ineffective and immobile government have more of a right to survive than the people with whom it shares the country? Why does Cuba belong more to the “revolution” than to me, or to the thousands (yes, thousands) of people who came out to protest on July 11?

Why are those who do not agree with the government’s management of Cuba called confused, counterrevolutionaries, ex-Cubans, or imperialist lackeys instead of being recognized, simply, as a sector of the population that wants change, as happens systematically in all countries around the world?

What new project can we Cubans dedicate ourselves to, if it is not possible to change our minds inside the country or organize projects as an alternative to those run by the government? How can we express discontent with any social situation when the right to peaceful demonstration does not exist on the island either, when those who suggest alternative or artistic forms of demonstration are accused of inciting crime and put in jail, as has recently happened with the visual artist Hamlet Lavastida?

Why prevent the existence of a non-official press in Cuba and of other, non-communist political parties? What intentions does it reveal when the State wants, in the 21st century, to have complete control over not only the press, but even the comments of users on social networks? For what other reason—if not to control the flow of information on these networks—did the Cuban government cut off the Internet throughout the island after the protests?

What will the Cuban government do to improve the lives of its people if the United States does not remove the economic embargo on Cuba tomorrow, or for another ten years? Let’s be clear, there are a bunch of shameless politicians in the United States who have only reached the Senate—and have remained there for years—under the pretext that they want to free Venezuela and Cuba of totalitarianism, yet do nothing humane to achieve it. Conservative politicians like Marco Rubio, who do not want Cuba to be free because they would lose their fake identities as defenders of human rights. So, if the U.S. government does not lift the economic embargo, what is the Cuban government going to do to improve life on the island? What are they going to do to ensure that tourists do not have more rights and better conditions than nationals? When is the Cuban government going to allow national citizens living abroad to invest and do legal business there?

It is said that the biggest mistake the Spaniards made when they launched their conquest in America was their failure to understand that their knowledge alone was not enough to appreciate the new universe they’d found, one full of different cultures. Why don’t the defenders of Cuban politicians realize that, if they do not live in San Antonio de los Baños, Palma Soriano, or, if like me, they have not lived in Cuba for years, they probably do not fully understand the country?

Hence, how limited will the understanding of the subject be among those who have never lived there, or whose knowledge of Cuba is reduced to three or four tourist vacations, or a former Cuban lover? Why not listen to the people who are there, in the eye of the hurricane, on the street, living day-to-day life? Not those who drive around Mantilla, or those who have been paid a million dollars to give a concert; no, because they don’t understand anything anymore either. Why not listen to the motives of the people who took to the streets, of those who went out to protest on July 11?

Why reduce the discomfort in Cuba to a group of brainwashed young people with Internet? If the struggle is only of that particular group, why are there so many images of elderly women protesting in the streets, and videos of so many mothers looking for their missing children after the protests? Why, if those mothers, fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers, helped build what they call the revolution do they not have now, 62 years later, the right to build something else, to change their minds, to want to try other political paths? Why can people in other countries change their minds, but not in Cuba?

No one with a broad sense of justice should wish for the military intervention of a foreign country in their homeland. But people also have to understand that, if a State imprisons a person for hours without following the due process of law, without providing information on the whereabouts of that person, that State is effecting a forced disappearance. Where are the people who disappeared on July 11? Why has the filmmaker Anyelo Troya, photographer of the video clip Patria y Vida, been sentenced to one year in jail, when artists and intellectuals have no other social function than to circulate ideas and leave behind their testimony of what is happening around them?*

Why is there no room in Cuba for Cubans who think differently from the government? Why does Cuba belong only to revolutionaries?

* Anyelo Troya was released after the original publication of this article. However, many of the people released after July 11—including journalists, artistas and minors—are being held in house arrest in flagrant violation of their freedom of speech.

Victor Gonzalez is a first-generation Cuban-American storyteller and former college administrator based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His work has appeared in Miami New Times, Phoenix New Times, and other alt-weekly publications. His Twitter handle is @ChubbyVictor.

Dainerys Machado Vento is the author of the short story collection Las noventa Habanas. She has been included on the Granta magazine list of the best young storytellers in Spanish. She is currently completing a Ph.D. in Modern Languages and Literature at the University of Miami. She is Cuban, and her Twitter handle is @Dainerys_MV.

@LiteralPublishing

Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Yo estaba de visita en Cuba en mayo de 2018, cuando el avión de Cubana de Aviación que cubría la ruta La Habana-Holguín cayó al suelo poco después de despegar, dejando un saldo de más de cien muertos y una sola sobreviviente. Recuerdo el miedo de tener que tomar un avión pocos días después para salir del país; la necesidad de apelar a las estadísticas, de que si había sucedido algo tan terrible era poco probable que pudiera suceder de nuevo tan pronto. Recuerdo la conmoción, la gente pasándose los videos más horrendos del accidente de celular en celular. Pero recuerdo, sobre todo, la cobertura que la prensa cubana dio al evento. Ante cada padre y madre llorando a un hijo, ante cada hija llorando a una madre, había un periodista cubano de un medio de prensa oficial que preguntaba: ¿y qué tiene usted que decirle al gobierno? ¿Qué le agradece a la revolución? Las respuestas, por supuesto, no eran siempre las esperadas. En el sufrimiento es más difícil que la gente mantenga apariencias políticas o ideológicas. En el sufrimiento somos viscerales, solemos decir aquello que resulta incluso inconfesable en tiempos mejores. Se caen las máscaras ante la sensación de que no se tiene nada más que perder cuando se ha perdido a un hijo o a una madre, o a un hermano, o cuando se ha perdido la esperanza. En esos días de cobertura nefasta confirmé que algo estaba irremediablemente roto en Cuba. Hacer de una tragedia humanitaria un tema político, un circo mediático de agradecimiento a la revolución y su gobierno era, como mínimo, un acto grotesco.

En mi país, hace mucho tiempo que el dolor dejó de ser humano, para ser político. La confirmación llegó el domingo 11 de julio de 2021, cuando miles de personas salieron a la calle a expresar su descontento, pero policía y ejército las silenciaron a punta de palo, siguiendo una convocatoria del presidente de la República, Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, para que “los revolucionarios” tomaran la calle. “La orden está dada,” dijo y las palabras se volvieron un manotazo encima de la mesa de la historia. Nadie me lo contó, yo lo vi. Nadie me pagó para verlo. Al contrario, en el mundo entero, cubanas y cubanos seguíamos con atención un acontecimiento sin precedentes en la historia reciente de la isla. Veíamos todo desde el asombro y el dolor, desde la incertidumbre, aún con el recuerdo reciente del miedo, del “mejor no te metas en problemas,” que se nos inoculó toda la vida.

Casi dos semanas después de los acontecido, en Cuba se sigue politizando ese dolor que lanzó a tantas personas a las calles, a clamar medicinas y mejores condiciones de vida. Porque la gente que salió a marchar el 11 de julio estaba pidiendo a gritos “libertad,” que bien se podría traducir en elecciones libres y democráticas cada cuatro o seis años; en pluralidad de partidos; en movilidad económica y social. Pero la gente también estaba en la calle porque, al menos en Palma Soriano, donde se dio una de las movilizaciones más grandes y la segunda de las que hubo noticias, no tenían electricidad desde las 6 de la mañana.

No voy a hablar aquí de la lamentable situación económica y espiritual en la que está sumergida Cuba hace décadas, ni de la marcada diferencia que divide a la población que puede recibir alguna remesa de la que no tiene apoyo externo, y solo le queda hacer colas de horas para conseguir alimentos, inventar el diario, pedirle al vecino un pan viejo. No hablaré del país donde te dicen “si no te gusta vete”, como si tú no hubieras nacido ahí y no lo llevaras también en las entrañas, como si no te doliera el dolor de la familia y los amigos que viven ahí. He hablado del tema muchas veces en los últimos años. Y, afortunadamente, gente cuya visión admiro enormemente ha analizado las causas del estallido y ha ido dejando un valiosísimo testimonio de la represión posterior. Las palabras de la académica cubana Odette Casamayor en Literal, publicadas al calor del momento, hablan de la desigualdad, de la pérdida de las utopías. El escritor Abilio Estévez analiza, desde su experiencia personal, la complejidad de lo acontecido en “Vengo de vivir entre los bárbaros”. El dramaturgo Norge Espinosa ha escrito, desde su casa en La Habana, “Cuba: entre el límite y la frontera”, una mirada sobre la necesidad de reconciliación en el país de la desesperanza. Mientras periodistas independientes en El Toque han hecho una cobertura regular de los eventos, difundiendo solo las noticias que han podido verificar antes; pero también analizando la legalidad o ilegalidad de todo lo acontecido después con los manifestantes. Aunque las cifras oficiales no existen, se calcula que más de 500 personas continúan presas o arbitrariamente detenidas, o sea: desaparecidas. Entre ellas hay, al menos, nueve menores de edad.

El 14 de julio, Alejandro Hernández publicó en Infobae el esclarecedor texto “Fiesta y velorio en La Habana”, donde presenta a Cuba como “una sociedad donde la desconexión entre la realidad de la calle y la propaganda oficial era, y sigue siendo, cada vez más abismal”. En inglés, Ruaridh Nicoll ha escrito para The Spectator, The Guardian y otros medios europeos, con la mirada privilegiada de un extranjero que ama a Cuba pero que, asombrado, ve a su gente perder el miedo. El actor y dramaturgo Junior García ha hablado y escrito, también desde adentro, en nombre de la gente que ha venido poniendo el cuerpo desde noviembre de 2020, para mostrar públicamente su desacuerdo con el trato que el gobierno cubano da a los artistas, a los intelectuales, a los disidentes. García es uno de los miembros más visibles del movimiento 27N. Y no quiero redundar en ideas cuando tanta gente talentosa y valiente ha alzado la voz con firmeza y claridad, con ganas de cambio y comprensión.

Sí tengo preguntas. Muchas preguntas. Algunas son para quienes niegan la necesidad de un cambio en Cuba. Otras son para el gobierno cubano, aunque sé que es muy poco probable que me escuche, como no ha escuchado a la gente que vive en la isla. Las preguntas llegan en un caos, como un caos han sido los sentimientos de los últimos días. Porque creo que en Cuba, como en cualquier lugar del mundo, el dolor también debería ser humano:

¿Por qué si crecimos escuchando que la revolución cubana se hizo por los humildes y para los humildes ahora a los humildes se les llama marginales, “ese sector”, un error de la revolución? En Cuba no hay escuelas privadas, ni religiosas. Cada ser humano que camina por la isla tuvo una educación pública, estatal y socialista. Cada “marginal” que pueda habitar ese país es producto de 60 años de educación no solo revolucionaria, sino doctrinaria. ¿Por qué llamar delincuentes y marginales a quienes salen a protestar? ¿No era de ellos y para ellos eso que llaman revolución? ¿No debería tener vocación humanística cualquier sistema político que se diga, no ya socialista, sino de izquierda?

El gobierno de Cuba ha declarado en la televisión oficial que la CIA y la mafia cubano-americana están orquestando otro intento para desestabilizar al país. Esta es una historia muchas, muchas veces repetida. La verdad es que el país luce bastante desestabilizado. Escuelas y universidades no han podido reabrir durante la pandemia y el sistema de salud colapsó en varias ciudades debido al incremento de los casos de Covid, que ha tenido varias oleadas, como en la mayoría de los países del mundo. En televisión nacional se ha afirmado que algunos de estos grupos estadounidenses han chantajeado a cubanas y cubanos para salir a protestar o para que creen la narrativa en las redes sociales de que los policías los han reprimido. El pago propuesto sería una o dos recargas telefónicas. Sí: pagar la oposición política con recargas. Si esto fuera cierto, ¿en qué condiciones viven miles de personas en Cuba que son capaces de salir a protestar contra el gobierno para ganarse una recarga telefónica, equivalente a 20 dólares y con fecha de expiración de un mes?

¿Por qué un proceso político que empezó llamándose revolución y que ha devenido un gobierno inefectivo e inmovilista, tiene más derecho a sobrevivir que la gente con la que comparte el país? ¿Por qué Cuba es más de la “revolución” que mía o de los miles (sí, miles) de personas que salieron a protestar el 11 de julio?

¿Por qué a quienes no están de acuerdo con la gestión del gobierno en Cuba se les llama confundidos, contrarrevolucionarios, excubanos, lacayos imperialistas y no pueden ser reconocidos, simplemente, como una parte de la población que quiere un cambio, tal y como sucede sistemáticamente en todos los países del mundo?

¿En qué nuevo proyecto podríamos trabajar cubanas y cubanos si dentro del país no es posible cambiar de idea, si no se pueden organizar proyectos alternativos a los del gobierno? ¿Cómo podríamos expresar descontento con cualquier situación social si tampoco existe en la isla el derecho a la manifestación pacífica, y a quienes sugieren formas de manifestación alternativa o artística se les acusa de incitación a delinquir y se les mete a la cárcel, como ha sucedido recientemente con el artista visual Hamlet Lavastida?

¿Por qué impedir la existencia de una prensa no oficialista en Cuba y de más partidos políticos que no sean el comunista? ¿Qué intenciones devela el hecho de que un Estado quiera, en pleno siglo XXI, tener completo control de la prensa e incluso de los comentarios de usuarios en redes sociales? ¿O por qué otro motivo, sino para controlar el flujo de información de las redes, cortó el gobierno cubano internet en toda la isla después de las protestas?

Si mañana Estados Unidos no quita el embargo económico a Cuba, si en diez años el gobierno de Estados Unidos no levanta el embargo contra Cuba, ¿qué hará el gobierno cubano para mejorar la vida de la gente? Porque, que quede claro, en Estados Unidos hay una pila de políticos descarados que solo han llegado al Senado y se han mantenido por años con el pretexto de que quieren liberar a Venezuela y Cuba del totalitarismo, pero sin hacer nada realmente humano para lograrlo; políticos conservadores como Marco Rubio, a quienes no les conviene que Cuba sea libre ni carajo porque perderían sus poses falsas de defensores de derechos humanos. Entonces, si el gobierno de Estados Unidos no levanta el embargo económico, ¿qué va a hacer el gobierno de Cuba para mejorar la vida en el país? ¿Qué van a hacer para que los turistas no tengan más derechos y mejores condiciones que los nacionales? ¿Cuándo va a permitir el gobierno cubano que ciudadanos nacionales, residentes en el extranjero, puedan invertir y hacer negocios legales en la isla?

Se dice que el mayor error de los españoles cuando iniciaron la conquista en América fue no comprender que su conocimiento no les alcanzaba para entender el nuevo universo que habían encontrado, lleno de diferentes culturas. ¿Por qué no se dan cuenta los defensores a ultranza de los políticos cubanos que, si no viven en San Antonio de los Baños, Palma Soriano, o –si como yo— no han vivido en Cuba durante años es probable que no entiendan a plenitud ese país? ¿Cuán limitada será entonces la comprensión del tema para quienes nunca vivieron ahí, o para quienes el conocimiento de Cuba se reduce a tres o cuatro viajes turísticos o a un antiguo amante cubano? ¿Por qué no escuchar a la gente que está ahí, en la caliente, en la calle, viviendo el día a día? Ni siquiera a los que andan en carro por Mantilla, ni a los que han cobrado un millón de dólares por dar un concierto, no, porque esos tampoco entienden nada ya. ¿Por qué no escuchar los motivos de la gente que salió a la calle, de quiénes salieron a protestar el 11 de julio?

¿Por qué reducir la molestia en Cuba a un grupo de jóvenes con internet y los cerebros lavados? Si la lucha es solo de ese grupo, ¿por qué hay tantas imágenes de mujeres de la tercera edad protestando en la calle, y videos de tantas madres buscando a sus hijes desaparecides después de las protestas? ¿Por qué si esas madres, padres, abuelas y abuelos ayudaron a construir eso que llaman revolución no tienen ahora, 62 años después, el derecho a construir otra cosa, a cambiar de idea, a querer intentar otros caminos políticos? ¿Por qué en otros países se puede cambiar de idea y en Cuba no?

Nadie con amplio sentido de justicia debería querer la intervención militar de un país extranjero en su propio país. Pero también la gente tiene que entender que, si un Estado mete preso por horas a una persona, sin seguir el debido proceso de la ley, sin ofrecer información sobre el paradero de esa persona, ese Estado está produciendo una desaparición forzada. ¿Dónde están los desaparecidos y desaparecidas del 11 de julio? ¿Por qué al realizador Anyelo Troya, director del videoclip “Patria y Vida,” se le ha dictado un año de cárcel cuando artistas e intelectuales no tienen otra función social que la de mover ideas y dejar testimonio de lo que acontece a su alrededor?

¿Por qué no hay espacio en Cuba para las cubanas y cubanos que piensan diferente al gobierno? ¿Por qué Cuba es solamente de los revolucionarios?

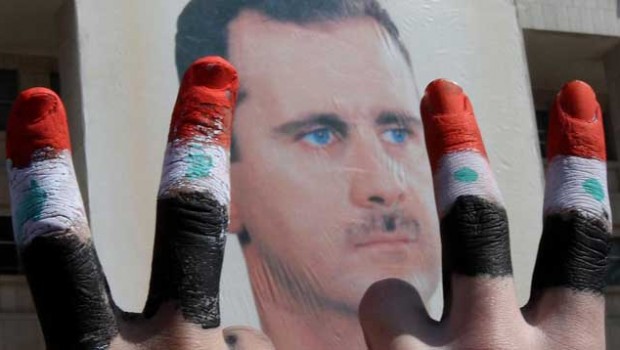

*Imagen de Pedro Szekely

Dainerys Machado Vento es autora del libro de cuentos Las noventa Habanas. Ha sido incluida en la revista Granta entre los mejores narradores jóvenes en español. Estudia su doctorado en Lenguas y Literatura Moderna en la Universidad de Miami. Es cubana.Su Twitter es @Dainerys_MV

Dainerys Machado Vento es autora del libro de cuentos Las noventa Habanas. Ha sido incluida en la revista Granta entre los mejores narradores jóvenes en español. Estudia su doctorado en Lenguas y Literatura Moderna en la Universidad de Miami. Es cubana.Su Twitter es @Dainerys_MV

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad.

Wow excelente !