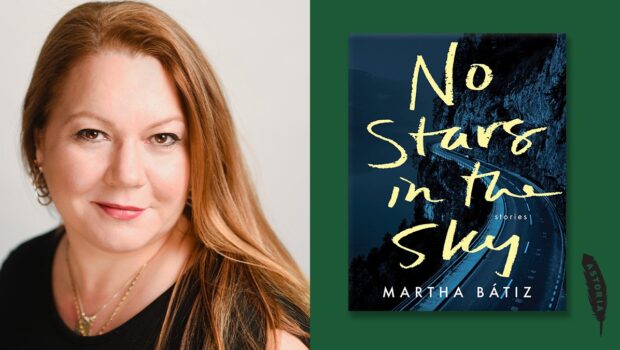

Martha Batiz´s No Stars in the Sky

Greg Walklin

Partway through the short story “Broken,” early on in Martha Batiz’s new story collection, an unbearably sad thing happens. Adela, whose daughter, Alma, has disappeared, spends most of her time wandering around an airport. Devastated is probably the word most people would use for Adela—but that seems plainly inadequate to describe her grief, which has twisted so far that she has become jealous of a mother whose infant baby died of a heart defect. “It gets Adela thinking about how lucky that mother was,” Batiz writes, “being able to cuddle her child as he died. Having a grave to visit.” Adela taught her own daughter to “never [go] out alone after dark” and to have “her phone at all times.” The nightmare, Adela finds, as she struggles to do something about her daughter’s disappearance, is that she never did anything wrong in the first place.

Though not all of the 19 stories in No Stars in the Sky are as pitch black, Martha Batiz’s new story collection paints with the bleakest of brushes. This is a volume of despair, and specifically the despair of women victimized by men—men who take advantage of circumstances, or men who employ politics or religion like blunderbusses. Batiz has produced several collections and a novella, among other publications, and possesses such a mature, pointed voice, that these stories are always purposeful, and not a word is wasted.

The volume is longer and richer than her last collection, Plaza Requiem: Stories at the Edge of Ordinary Lives. Those stories focused on the family, and family breakdowns, and it’s no surprise to see her exploring similar veins in this book. Parental despair absorbs the main characters in “Rear-view Mirror” and “Jason,” which both confront the intractabilities of parenting adolescents struggling with their mental health. In one story, the son commits suicide; in the other, the mother notes that her depressed teenager, Abby, would prefer, if given the option, her mother’s death over never having internet access again. Both stories succeed because of how realistically impossible their circumstances feel—how the mother-protagonists seem unable to fix what has been broken, and how every action and reaction is wrong.

Some of the strongest stories are the ones specifically, and firmly, rooted in their history and time. Canadian politics, violence in Mexico and Argentina, the COVID-19 pandemic: these are not just background, but an essential part of the stories’ shape. “Svetlana of Montreal,” which rivals “Broken” for its hopelessness, takes place just over the course of a single, snowy afternoon, but the riveting backstory conveyed by Svetlana, the grandmother of the late Ivan, to Anastasia, Ivan’s fiancé, stretch all the way to the Russian Revolution (the snowstorm being a once-in-a-hundred year type is a clever nod). Ivan died tragically before he and Anastasia could marry, and Svetlana uses the snowstorm to tell Anastasia about Svetlana’s own tragic past. The old woman has reduced her life to a single axiom: “Nothing is crueler than hope.”

“Kamp Westerbork” also pulls together Pablo Neruda and World War II to crystallize a mysterious chapter in the family’s past, and to explain echoing family resentment. The trauma in “Dear Abuela” stems from the atrocities of the Argentinian dictatorship. More than one tale stem from endemic violence in Mexico. And the final story, “Helen’s Truth,” is an imagined apology (in the Socratic sense) of the daughter of Zeus, whose face famously launched a thousand ships. Helen provides a sort of peroration for No Stars in the Sky:

But as I said before, no woman has ever been the true cause of any war. Proud men, eager to cleanse with blood the affront of my absconding, dragged countless innocent lives towards their untimely end just to satisfy their vanity. I will never feel sorry for that. What I will be forever sorry for — no, sorry is too insignificant a word to encompass the incommensurable pain I have hidden for too long — is what I was forced to do when the war was closing in on us.

“Helen’s Truth” was prefigured throughout the book, as Batiz has woven a number of classical allusions (beginning with the the title of the first story, about the teen suicide; fittingly, Medea herself is later referenced in “Rear-view Mirror”). But it also like a proto-narrative, showing that women have been victimized for as long as stories have been told—mistreated, objectified, dehumanized. (Helen’s impossible choice also recalls the desperate decision Sethe made in “Beloved.”) In another story, “The Audition,” the musically talented Genesis is forced to debase herself in order to get out of her misery—her own country—once and for all. The trap Genesis finds herself in has, it seems, been there since the beginning.

Dislocation also features strongly in “Uncle Ko’s One Thousand Lives,” about a man trying to come back from being a political prisoner, in “The General’s Daughter,” about the disappearance of a live-in maid, and in “Fiat Voluntas Dei,” a confrontation between a daughter and her radicalized father. Batiz, herself a writer born in Mexico but living in Toronto, employs many characters originally from Central or South America who live in Canada. Anastasia in “Svetlana” has found herself nearly alone and up north, learning from another woman who has been dislocated; just the same, the narrator in the epistolary “Dear Abuela” has been pulled far away from the source of her trauma, at least physically. Struggling to confront her past trauma, she agonizes over returning to Mexico for the funeral services of her grandmother, and so writes a letter her abuela will never receive. In this story, Batiz plumbs trauma and and its flip side, guilt. The narrator has been attending a support group for victims of torture, and this story demonstrates how guilt can morph and twist, and how confronting it is like trying to pin gelatin against a wall. “This is Toronto, Abuela,” she writes, “there are people here from all over the world, and some of them have gone through unimaginable hardship.” What was her experience, she wonders, against that of a Congolese woman whose hands were cut off? Like the awful comparisons that Adela makes in “Broken,” this is the ratiocination of a beleaguered soul.

It’s testament to the bleakness of this book that some of the scariest—or more conventionally scary—stories actually prove to be a sort of respite. “The Last Piano” was creepily reminiscent of “Ants” from “Plaza Requiem.” “She Who Laughs Last,” about the disappearance of a man, is another taut, twisted tale, which feels a bit like an ode to Stephen King.

After Abby’s boyfriend in “Rear-view Mirror” dies swerving in the road to avoid a cow, which was chasing after its calf, Abby’s mother can’t help but wonder about her own daughter’s fate. “And Abby?” She thinks. “Who will give their life to save Abby?” This book clearly answers: Nobody. The title of the book may allude to Cassius’ famous line from “Julius Caesar“: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, / But in ourselves, that we are underlings.” Their are definitely no stars in this book, but neither does it seem that the women have much of a chance. One character, in “Apartment 9B” notes, “Silence is the one thing I don’t fear.” Another, in “Old Wounds,” claims that “[t]he real punishment is having time to think.” The women in these pages must somehow deal what they are given—or to more accurately put it, what hasn’t been taken away. How can one do that, when such large obstacles—history, the government, criminals, the patriarchy—stand in the way?

Revenge, even if slight, seems to be the only channel for their grief; certainly it was, in a way, part of Helen’s choice (and Cassius’s, for that matter). “She Who Laughs Last” is a tale of retribution. The estranged daughter in “Fiat Voluntas Dei” finds some consolation in the pain she is able to inflict back on her radicalized father, who hides behind his religious extremism. “His face must be hurting,” she notices. “And that thought makes her smile.”

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. His book reviews have appeared in The Millions, Necessary Fiction, The Colorado Review, and the Lincoln Journal-Star, among other publications. He has also published several pieces of short fiction. Twitter: @gwalklin

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: June 6, 2022 at 9:38 pm