At Sea

So Mayer

Black rhinos are critically endangered; middle-class straight white men are not – and yet, here they are on a yacht, in Athina Rachel Tsangari’s third film Chevalier, acting like they’re the center of the universe.

But their universe is imploding.

Tsangari’s first film, Attenberg, took a melancholy, even devastating look at a young woman’s relationship with her dying father. A bitterly funny absurdist comedy, Chevalier marks a turning point for the director. Yet behind its moments of tenderness and silliness lurks a biting political critique.

The black rhino is no idle term of comparison: indeed, some do appear (in a manner of speaking) later on in the film. The plot of Chevalier is structured around an increasingly dramatic series of arbitrary challenges through which the men prove themselves to each other, culminating in the surreal vision of all six of them racing to build flat pack CD towers on deck. They turn the boat into a weirdly-turreted castle whose phallic point underlines a spectacular earlier scene featuring a persistent erection. The towers are black lacquer, and the boxes they arrive in are marked RHINO. It’s a typically waspish, blink-and-miss-it jab from the brilliant Tsangari. It combines her love of off-kilter verbal language – speeches and songs here veer from deadpan to diva – and her abiding fascination with humans as just one more species in a diverse world.

Attenberg took its title from legendary British TV naturalist David Attenborough, whose documentaries are a rare form of communication between Marina and her father Spyros. Here Tsangari’s cinematic eye was informed as much by the wildlife documentary as by the ‘dead time’ of Michelangelo Antonioni, with whom her work has been compared. The men in Chevalier are on a spear-fishing trip, which brings the viewer immediately into the non-human world, although underwater photography is used very judiciously in order to keep the focus on these strange fish out of water. Moreover, chevaliers are knights, not sailors, thus these men are doubly out of their element.

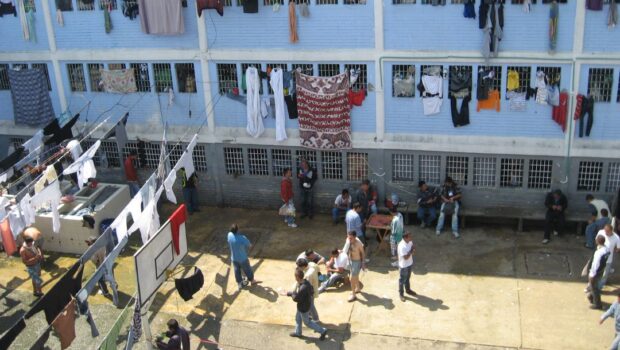

The film opens with the male characters crawling out of the waves onto a deserted beach, not unlike the tetrapods of 367 million years ago –a scene that is hard not to interpret in tandem with Lucile Hadzihalilovic’s second film Evolution, a dark fairy tale about male adolescence on the sea shore. But Tsangari’s adult men, for all their absurdism, are very much of the real world – although the knock-out blow of her argument doesn’t land until the final scene. Throughout the film, we’ve seen the hired cook and his assistant taking bets on the competition ‘upstairs’; there’s a feeling of complicity between the viewer and these unnamed men, as spectators who are outside (and somehow morally above) the ridiculous sleep-assessing and blood-testing blokes who have hired the boat. But they eventually disembark in Athens, wheeling their luggage to their separate cars, going home to their wives and secure employment. Meanwhile, the cook and cleaner have a heap of bloody towels to deal with and are embroiled in their own version of the all-encompassing contest. Only the stakes are far higher for them: it’s not about winning the symbolic chevalier ring of the title, but about who gets to keep his job.

Like an inverted version of Jean Genet’s play The Maids, in which the sisters imitate (and eventually murder) their oppressive employer, Chevalier shows the way in which ‘upstairs’ discourse – the name-calling and dick-measuring, the insistence on a random measure of excellence which is also a measure of straight white masculinity – finds its fullest, most damaging impact below-decks. The spear-fishers can play at hunting because they don’t need fish for food; they can play at medical testing because they can afford healthcare; and if they don’t like something, they threaten to “hide in the toilet and eat salmon carpaccio.” It’s all a game because they’ve already won all the privilege. But all that jockeying for power, all the bullying and betrayal, translates into a social norm that is then desperately carried on by those who can’t escape.

It’s no coincidence that most of the film takes place on a boat moored off the coast of Greece – with nary a one of those other, well-reported boats in sight. Here is Nero fiddling while Rome burns, or the European élite lip-synching to Minnie Riperton and reading porn to each other while refugees drown and starve. In fact, the apocalypse may have already come and gone: we see no other people, except for a couple of wives and girlfriends on Skype. That absence of women is part of the absence of what could be called, for want of a better word, humanism among the men, of any outward, inclusive vision. While it is Dimitris, the beta-male character, who lip-synchs gorgeously, he finally gives in and offers his buttock to seal the blood-brother ritual at the close of the contest, participating in the macho bullshit in his own way in order to be accepted.

In The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Le Guin has her protagonist, Shevek, who has grown up in a gender-equal anti-materialist anarchist society, observe with regards to a spaceship from a capitalist society where gender and racial hierarchies are rampant, that while there are no women on the ship, every piece of furniture is luxurious and seductive so that “he felt a woman in every table top.” There may be no women on screen in Chevalier, but – because of their deliberate absence – they are present in every piece of furniture, every reference to fish, every mournfully empty harbour, every voice, every gold chevalier ring. As a female viewer, I realized just how much time I spend at the cinema looking (but not really being allowed to look) at men – or allowed to look but not to measure, to compare, to state, because men are the measure of all things. And because men rarely look at each other in heteronormative cinema, we don’t have a good guide for how to look at them, or at what all their covert looking and competing means.

Except now we do.

In a world of superhero cinema, where screen entertainment supposedly comes from CGI-d white male actors out fake-smashing each other against greenscreen, Tsangari drops her anchor against the deep blue of the (feminine: I think it has to be read as such) sea and tears away the special effects to reveal the flabby egos beneath. Here we have the masters of the universe swapping dick pics and arguing incoherently while the world falls to pieces. The film as a whole unfolds the perfect insult for the world political class (and certain prominent members in particular) that Tsangari and co-writer Efthymis Filippou fire midway through the film: “Your syntax is shit, and your dick is very, very small.” Go tell it to all the wannabes competing for that little gold ring of power.

![]() Sophie Mayer is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound and The F-Word.She’s the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema and The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism andDocumentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

Sophie Mayer is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound and The F-Word.She’s the author of Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema and The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, and the co-editor of Catechism: Poems For Pussy Riot, The Personal Is Political: Feminism andDocumentary and There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking and Beyond. Her Twitter is @tr0ublemayer

Posted: July 6, 2016 at 10:13 pm