Mexico As Seen From Mexico

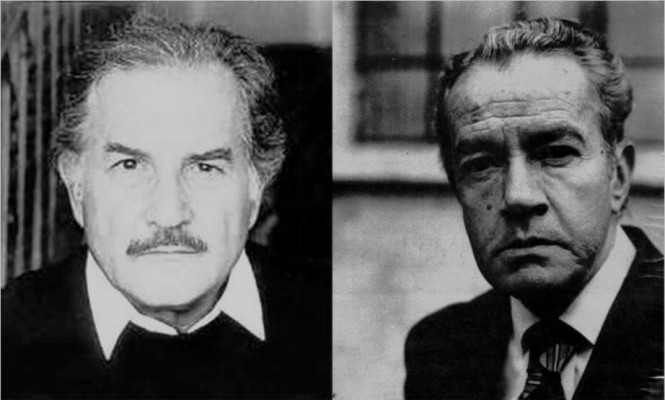

Martín Solares

Translated by Tanya Huntington

In Battles in the Desert, one of the best novels about growing up in my country and beyond a doubt, one of the most widely read and beloved, José Emilio Pacheco recalls that sixty years ago, during the administration of President Miguel Alemán, maps were used to teach schoolchildren that Mexico is shaped like a cornucopia. An era of economic development and hope for the future that seems all too distant now that Mexico has ostensibly taken on the shape of an AK-47, also known as a cuerno de chivo or goat’s horn (the assault rifle favored by local criminals).

As one of the editors who will be attending the book fair in London this year, the organizers have invited me to write a text about my country, to be published on their blog. I am grateful for the invitation, but cannot accept it unless I am allowed to express myself with all of the frankness at my disposal.

For once, our national political analysts can agree on something: Mexico is undergoing one of its worst crises since the Revolution of 1910. No matter what their politics, who can back our policies in light of the incessant corruption scandals? Who can believe in a system of imparting justice that propitiates impunity and that over the past few months alone, has fully exonerated drug trafficking kingpins such as Rafael Caro Quintero or Sandra Ávila Beltrán –not to mention Raúl Salinas de Gortari, imprisoned in the mid-1990s and considered at the time to be one of the most emblematic cases of inexplicable and, in all likelihood, illicit affluence in our country? Who can look optimistically toward the future in Mexico when 43 students have disappeared in Guerrero after being arrested by a police force that should have protected them? How are we to believe in the integrity of our ministers, or even of our president himself, when they are surprised incurring in conflicts of interest that in other countries, would suffice to demand their resignations? Our ambassadors are asked to improve the image of the country abroad; indeed, we would like to see the same determination among our local ministers to improve the lives of Mexicans here at home.

Social uprisings have become frequent and widespread. One need only cast a glance at social networks or national headlines to get an idea of our vast disenchantment and even vaster indignation: citizens known for being patient and submissive have turned out in the streets to protest en masse, fed up with the path of injustice and misery Mexico has chosen to take over the past few decades.

All evidence points to the fact that our representatives have abused a cocktail of privilege and impunity. Where can we find a deputy who ought to be in the Chamber of Representatives, studying the laws that make life in our country feasible? Why, watching the Super Bowl in the United States of America (from the front row, of course). And where might we find a governor as a catastrophe takes place or a mass murder is discovered in the territory under his charge? In all likelihood, he’ll be in Las Vegas or in Europe on a pleasure jaunt, all expenses paid by the people whose rights he is supposed to be defending. To what political party does the mayoral candidate caught on film at a party with prostitutes belong? To the most conservative, obviously, and one that claims to defend family values to boot. Who was caught negotiating the illegal sale of a protected beach to an international consortium? The leader of the Mexican environmental party, naturally: everybody knows that. And who was that drunk who crashed an SUV into a public park at top speed? Undoubtedly the representative of one of the delegations of Mexico City who, among other duties, is supposed to ensure that no one exceeds the speed limit on his watch. And back to my own broken record: why have the inhabitants of Tamaulipas been abandoned to their fate, compelled to coexist with shootouts, extortions and kidnappings? Why do armed confrontations between drug traffickers continue throughout the state, and yet no one decries the ungovernable nature of many of its cities? Why have three of the past four governors of Tamaulipas been accused by the DEA of having connections to drug traffickers, and why hasn’t a peace commissioner been named to supervise current developments in the region? All of us would like some answers to these questions.

Given the current situation, who dare speak now of the marvelous beaches of Mexico, its fascinating pre-Hispanic ruins, its gorgeous colonial cities, its indescribably tasty cuisine and the legendary friendliness of its inhabitants, when the possibility of living in a peaceful society that respects human rights seems just that: an unspeakable ruin, a mirage, or a legend?

No matter how you look at it, we are suffering the consequences of the ongoing plundering politicians and strongmen have perpetrated against our country over the past century. In 1929, the generals who won the Revolution agreed to hold elections every six years in order to prevent anyone from wielding power in perpetuity, and so all the loot was divided among different factions of the same group of politicians, all of them flocking to the National Revolutionary Party, which changed its name to the Party of the Mexican Revolution and then to the Institutional Revolutionary Party.

But while changing the label, the party never bothered to refine its ideals. Every six years, our governors assure us that they are convening honest and impartial elections, and people flock to the polls, albeit with increasing disillusionment. Anyone can attest to the fact that little by little, some parties have received a greater quantity of ill-gotten gains, while others enjoy broader coverage on television in exchange for future privileges that will be extended to the broadcasters involved, and a few will even buy the vote of our poorest citizens with money stolen from governments representing different regions of the country (see, for example, the public debt of the government of Coahuila, or the scandal unleashed by notorious compensations to voters via Monex gift cards).

No one finds it strange anymore that even when the exit polls have announced the triumph of a candidate from the opposition, something will go wrong in the national vote counting system, causing it to “crash” or break down —which is what took place in 1988, when everything augured the triumph of a leftist presidential candidate, the engineer Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas. Or when “an algorithm” fails among the computers in charge of tallying the votes, as was the case in 2006, when everything pointed to the triumph of Andrés Manuel López Obrador. But we will continue to call this fiction a “democracy”, because with the exception of The True Story of the Conquest of New Spain, by Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Pedro Páramo, by Juan Rulfo, or La muerte de Artemio Cruz, by Carlos Fuentes—three ideal books for those interested in getting to know my country a little better—the integrity of our political system is the most widespread fiction in national territory.

The fable of democracy rendered such good results for so many decades, that it is worthwhile to ask ourselves whether we aren’t on the verge of emptying that horn of plenty. Will we go the way of the Argentineans, who woke up one day to discover that a considerable portion of their natural resources lay in the hands of foreign businesses? Being an optimist myself, I say no, it will not happen to us. I am convinced that we Mexicans have worked hard to forge our own destiny: indeed, we are more likely to repeat the experience of Colombia in the 1990s, when purveyors of drugs sought to impose their ideals and convictions on the rest of the country. There, they crashed a truck with explosives into the National Congress building. Here, their colleagues in the state of Michoacán launched grenades against the local populace while they peacefully celebrated Independence Day on September 15, 2008.

None of this is new. We got ourselves into this crisis because all those years of robbery and poverty created the ideal terrain for the flowers of impunity to bloom: the latest in Mexican violence, available in all shapes and sizes. Fascinated by cinema and the American way of life, the most ambitious and least scrupulous of our merchants dedicated to politics or drug trafficking have promised this same lifestyle to their employees and business partners if and when they respect the style, but not the lives, of all those who are opposed to their modus vivendi. Thus, a criminal capitalism has gestated that is no longer directed by wolves, but rather by jackals, thereby producing the current state of affairs in Mexican society.

My friends from the London book fair will forgive me for not sharing a beautiful article or fictitious tale about our magnificent beaches, or ruins, or colonial cities (they continue to be magnificent, truth be told: one need only travel to Campeche, Tulum, La Paz, Puerto Escondido, Punta Mita, or Puerto Vallarta; to Monte Albán, Tenochtitlán or Zempoala; to Zacatecas, Puebla, San Luis Potosí or Querétaro; to name just a few destinations). Because lamentably, these stories do exist. Indeed, we all know of people who have died because of them. In the state of Veracruz alone, 11 journalists have been murdered for doing their jobs since 2010, over the course of the administration of Governor Javier Duarte. And for the third time: in Tamaulipas, people attending the Fiestas de Abril festivities in 2014—believing that the armed confrontations between various criminal groups had ended and that the city was enjoying a respite, as official propaganda claimed it was—were forced to take refuge from a hail of gunfire. It is still uncertain how many casualties there were during the barrage, because the official count came to a halt after reaching several dozen.

The most worrisome aspect of this kind of criminal fiction is that it clones itself so suddenly and travels so quickly that if we do nothing to stop it, it could soon take root in any city of the world. Among those texts written with eyes wide open are found the chronicles of Marcela Turati, Alejandro Almazán, Diego Osorno, Témoris Grecko, Juan Villoro, Sergio González Rodríguez, Carlos Velázquez and Fabrizio Mejía as well as the stories and novels of Orfa Alarcón, Yuri Herrera, Fernanda Melchor, Juan Pablo Villalobos, Antonio Ortuño, Iris García-Cuevas, Enrique Serna, Eduardo Antonio Parra, Daniel Sada, Francisco Hinojosa, Luis Felipe Lomelí, Julián Herbert, Luis Jorge Boone, Miguel Tapia, Élmer Mendoza, Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Jennifer Clement, David Lida, Francisco Goldman and Londres después de medianoche, by young Mexican writer Augusto Cruz.

While the fiction that intends for us to live in tranquility tries to impose itself, literature and literary journalism are building a few singular attempts to show another side of Mexico that is painful, but true. They remind us that one of the functions of literature is to act as an antidote against the lies of propaganda. Thanks to their capacity to create this vision, they constitute one of the few regions I still find admirable in this country.

PS: If you wish to learn more about Mexico, I also recommend the extraordinary short stories of Juan José Arreola, Fabio Morábito, Alain-Paul Mallard and Ignacio Padilla; the novels of Jorge Ibargüengoitia, Fernando del Paso, Salvador Elizondo, Vicente Leñero, Mario Bellatin, Jorge Volpi, David Toscana, Brenda Lozano, Valeria Luiselli, Guadalupe Nettel, Daniela Tarazona, Jorge Harmodio, Alberto Chimal, Cristina Rivera Garza, Alberto Ruy Sánchez and Álvaro Uribe; and the poems of Francisco Hernández, José Eugenio Sánchez, Julio Trujillo, Tedi López Mills, Myriam Moscona, Carla Faesler, Malva Flores, and Ricardo Yáñez.

Martín Solares is a Mexican writer, critic and editor who received the Efraín Huerta National Literary Award in 1998. He is the author of the novel The Black Minutes among other titles. Follow him on Twitter at @martinsolares.

Martín Solares is a Mexican writer, critic and editor who received the Efraín Huerta National Literary Award in 1998. He is the author of the novel The Black Minutes among other titles. Follow him on Twitter at @martinsolares.

Posted: March 17, 2015 at 5:28 am