Miguel Ángel Ríos “Merged with Vastness”

Johannes Birringer

Entrance to the gallery, with Double Vision, acrylic on canvas, 90×179.4 cm, 2023 [r]. Photo: J. Birringer

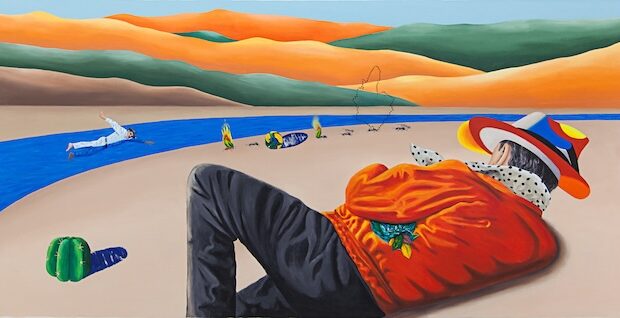

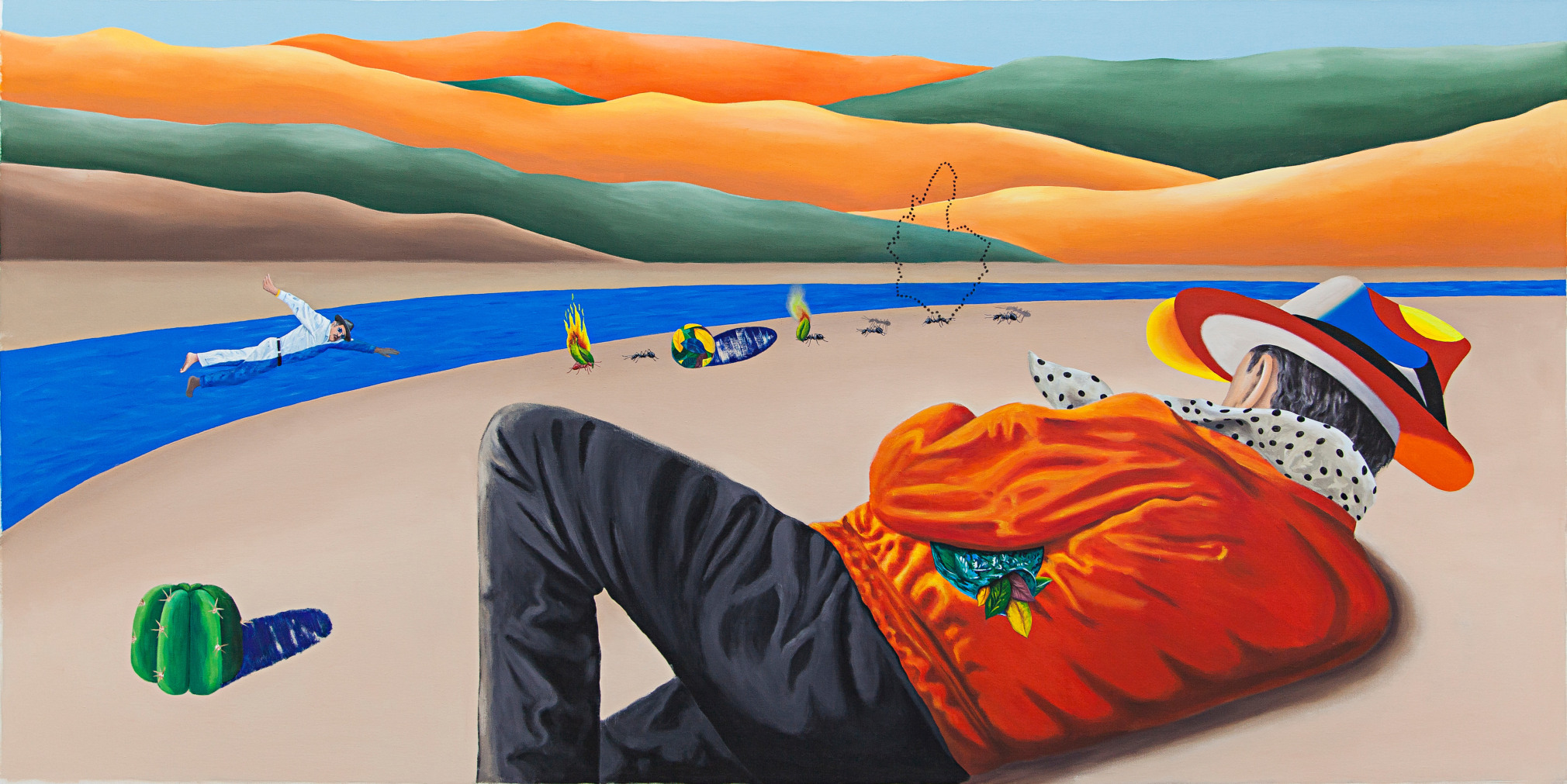

When you enter Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino Gallery, you are in a small foyer which on your left forms a lovely right-angled cubicle – here the title of the show appears on the wall faced by one of Miguel Ángel Ríos’ new landscapes that promise to merge the object that appears (in the foreground, in this case) with the vast expanse of territory. The painting is titled Double Vision and features in fact two plant objects, green and yellow cacti, that are shadowing each other, one large, one small, divided by swathes of bright orange, red, yellow, green and brown color masses that stretch out like ambling mountain ranges, horizon lines that could also be the limbs of a giant body stretched out. The “stretching out” is a recurring metaphor, and the dominant stylistic element of the canvasses.

As we continue into the exhibition, we encounter more of these wide-screen stretches of surreal color; they resemble an abstracted symbolic dreamscape, perhaps associated with an idea of Mexico, or the Andean regions in Bolivia and Peru. Knowing the artist’s biography, one recalls his childhood in the Calchaquí Valleys, Ríos’ Catamarca homeland in Northern Argentinia, and his later migrations to New York City and Mexico. The notion of migration came to my mind when I stepped into the large gallery, where on three walls we see five medium sized (including one smaller horizontally stretched canvas) paintings of the same

psychedelic color palette, faced on one side by an enormous early painting from 1989, In the middle of nowhere (370×522 cm).

Miguel Ángel Rios, In the middle of nowhere, acrylic on burlap, 370×522 cm, 1989. Image courtesy the artist and Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino

The large canvas is shockingly complex, filled with what might be a secret or forgotten language of hieroglyphs, Aztec pictographs and ideograms, glyphs that resemble plants and snakes. These ideograms could also be made up by the artist who is tricking our imagination, drawing these undecipherable bulbs that look a little bit like plants or mushrooms but could be tiny water towers. In the middle of the enormous canvas appears a skeleton figure – a portrait of the artist as a young man (with hat on his head, another reoccurring aspect of Ríos’ depictions of himself as an older man now lost in the vastness of the mountains). As an autorretrato, In the middle of nowhere may well refer to his childhood, remembered as a boy on empty Catamarca land (the next farm, he told me in conversation, was seven kilometers away), to a sense of isolation that compares fragile figures (sometimes even just outlines) against the vast immensity of the landscape.

Born in 1943 into a region mostly mountainous with a mix of valleys, some fertile and others very arid, as it is characteristic for the Andes, the deserts, salt flats, volcanoes, and diverse landscapes that include gorges and high dunes make it a region with a very rugged relief and varied terrain. The figure is recalling such an arid land and his time as a young autodidact, given the ominous name Miguel Ángel by his mother. He later studied art at the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires before moving to New York in the 1970s to escape the military dictatorship in Argentina. The painting evokes a spinal fragility to me that is haunting. I see also a figure in a Procrustean dilemma, or a dancer that actually rehearses to move, perhaps, to the rhythm of pointed arrows of the snake-like glyphs, inside a imaginary spirit map that foreshadows the later hand-made maps Ríos created in the 1990s. In that phase of his career, he began creating a series of maps, which he carefully folded and pleated by hand. Marking the 500th anniversary of the so-called discovery of the Americas, Ríos’ maps indicate the longue durée (a term coined by the French historian Fernand Braudel) of power and colonial experience, also paying homage to traditional Indigenous arts in the Americas (including the Andean quipu).

Miguel Ángel Ríos, Merge with Vastness, Acrylic on canvas, 10 ¼ x 41 ⅜ inches, 2024. Image courtesy the artist and Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino

The dancer also recurs in some of the video works that choreograph the violence of a struggle, the games of power (e.g. in Aqui [2007], with the ballet of trompos; or in Crudo [2008] with a white-suited tap dancer swinging two ropes with meat on each end –suddenly barking dogs enter the frame one by one until the dancer is surrounded).

The empty vastness of undulating mountain landscapes, devoid of humans (as it also very often appears in his video works), may well be implied by some of the paintings. The here formal choice of the garish, psychedelic colors suggests otherwise. There are also small rectangular canvases (7.8x31cm; 26×105.1cm) that toy with our sense of knowing the tradition of large 19 th century sublime landscape painting (Turner, Constable, Cole) or late 20 th century overreachers (Anselm Kiefer). The zoom down to a small sliver-landscape with dog. The dog looks at a cactus, as if puzzled, and there is red figure in flight, another dancer moving off center. This other, off-side, we begin to realize in the marvelous, thought-provoking exhibition, is the artist’s sense of seeing himself double in hallucinatory states, induced by plant-based drugs or the thin air, or he sees his doubles through the eyes of a dog. A shadow face shoots at the viewer with a slingshot, as if the dark figure wanted to warn us, not to come too close to Be careful, an acrylic/oil painting of 2023.

Miguel Ángel Ríos, Be careful, Acrylic on canvas, 120×277.7cm, 2023. Image courtesy the artist and Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino

The small double is fragile, sometimes drawn as silhouetted figure, shadowy outline of the man that is disappearing in De lo visible a lo invisible (2023).

Miguel Ángel Ríos, De lo visible a lo invisible, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 91.8x220cm, 2023. Image courtesy the artist and Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino

During journeys through diverse mountain regions, Ríos explored both botanical and ritualistic knowledge of indigenous customs, and especially those ancestral practices that tapped into medicinal and hallucinogenic expansions of the mind. I do not see Ríos being attracted to a spiritual connection or merger with nature and the environment. Nor would I recognize any merging with Earth or Gaia; and certainly there are no more gods, as Nietzsche told us. There are dogs and mules (in his 2014 video Mulas, shown together with Landlocked in a separate room of the gallery), and a few tiny ants. Rather than reaching for a spiritual dimension or enlightenment, Ríos is a trickster figure who plays with us, laughs behind his mask as in the strange face he paints in Territorio de la Mente (2024), hanging down from a snake-like cable that opens out into a blossoming red flower petal inside which the Joker is inserted.

This clownesque character of the work is as astonishing as the vigorous struggle of the five dogs in Landlocked, who seem of have dreams of the Pacific and desperately dig through a wall of sand and soil in the high mountains of Bolivia and Chile, as if they could breach the wall and reach the ocean. They hear the water or have picked up its scent, tunneling forward. Or do we only imagine hearing what they hear? Are we equally intranced by the impossible, sand flung in the eyes by the hindlegs of digging dogs (named Pila, Filpo, Trompito, Chiquita and Horrible)?

Miguel Ángel Ríos, They stole the map of my town, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 94.4×188.5cm, 2023. Image courtesy the artist and Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino

The most vexing work is a painting in which we see the artist, laying sprawled across the foreground, with his back to us and coca leaves under his left arm, looking at his smaller double swimming in a curving river in front of the mountains, while on the near shore there is strange congregation of ants, burning plants, and a hovering outline that is magically diffuse, a cactus dreaming itself. They stole the map of my town stretches further the vision of the artist seeing himself double, as in Do lo visible a lo invisible, where we can see at least two silhouettes in front of the artist, and one further behind that is heading in the same direction – a half-double that Ríos paints with two shadowy colors, pink-grey and brown.

The surprising pink is also the color of a foregrounded cactus in Different time in the same frame, a painting in which a dog on center stage watches the puny contours of the man with the hat, heading nowhere. In this exhibition, one trusts that Miguel Ángel Ríos has reached a state of calm resignation, a turning inside and reflecting on our delusions. In these landscapes he now paints, there are no more power struggles that betray the deadly wars and conflicts in the geopolitical theater of operations, the disasters caused by climate catastrophe. We do live in different times now, times of a crisis that will not end well for the planet. Ríos, the artist who has explored his hemisphere throughout a very productive life, seems to be in the state that the Japanese call hikikomori, withdrawing from the pressures of the social world, receding into an expansive inner state. The mulas in the video, two animals carrying packages of a white powder on the saddle backs, have also withdrawn, slowly and patiently climbing to the top of a steep hill. They take a look, and descend again. We see them wading through tall grass, and at some point enter into a wild mulas trance dance during which the sacks of white powder rip open and swirl through the air leaving their dusty trail on empty land.

*Sicardi | Ayers | Bacino Art Gallery, Houston

January 18 – March 8, 2025

Johannes Birringer is a choreographer and media artist. He co-directs the DAP-Lab, and has taught Performance Technologies at Northwestern University, Ohio State University, and Brunel University London. He authored Media and Performance (1998), Performance on the Edge (2000), Performance, Science and Technology (2009), Kinetic Atmospheres: Performance and Immersion (2021), and edited numerous transdisciplinary books incl. Dance and Cognition (2005), Dance and Choreomania (2011) and Things that Dance (2019).

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.

Posted: January 30, 2025 at 9:50 pm