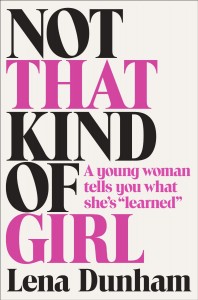

Not That Kind of Girl

Mercedes Trigos

Not That Kind Of Girl

by Lena Dunham

Lena Dunham’s book, Not That Kind of Girl, is a witty and often hilarious collection of personal essays, food journal entries, lists, and never-sent emails that offers a number of experiences Dunham considers “made” her the woman she is today. “Maybe,” Dunham claims in the introduction, “as Helen [Gurley Brown, editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan magazine for thirty-two years, advocate for women’s sexual freedom, and inspiration for the book] preached, a powerful, confident, and, yes, even sexy woman could be made, not born. Maybe” (xvi). The book is divided into five sections, “Love & Sex,” “Body,” “Friendship,” “Work,” and “Big Picture,” although these divisions are not as strict as their titles may suggest. Despite the various topics they deal with, sexuality seeps through all but two of the twenty-nine pieces in the collection, leading us to conclude that, for Dunham, sexuality is, if not the, at least a most crucial part of a girl’s learning journey towards becoming a young woman (I am purposefully using language from the book’s subtitle here, “A young woman tells you what she’s ‘learned’”). Not That Kind of Girl places sexuality at the forefront of women’s identity formation; a woman is made, Dunham’s memoir seems to argue, as situations allow or force her to explore sexuality.

Dunham’s approach is empowering for women in the way that she unapologetically asserts herself as a sexual being. However, it also appears to suggest that a woman does not make herself; she depends on her experiences—which she has little to no control over—to be made. The structure of the book supports this reading. The essays that cleverly narrate discrete occurrences and their influence on Dunham provide only a fragmented picture of the author, offering a very limited sense of continuity to the collection. The author discusses a wide array of happenings with an undeniable sense of humor, but they seem to be connected only through the mention of sexuality. Some of these experiences include feeling that she was “being desexualized in slow motion, becoming a teddy bear with breasts” because her boyfriend at the time would not have sex with her (19), “finding a lubricated prop condom stuck between [her] butt cheeks seven hours after arriving home” from filming a TV sex scene (102), and even dreaming about summer camp: “Our bunk was still intact, and so was my hymen” (251).

The book’s open and blunt engagement with sexual situations has caused anger and outrage in some readers. Ben Shapiro’s conservative site TruthRevolt published an article entitled “Lena Dunham Describes Sexually Abusing Her Little Sister”that quotes the essay “Who Moved My Uterus?,” in which Dunham explains that, when she was seven years old, “[her] curiosity got the best of [her]” and she “leaned down between [her younger sister’s] legs and carefully spread open her vagina” (121). Various other articles about the controversy have quickly surfaced after this first one, both accusing and defending Dunham, and social media platforms have exploded with posts denouncing and supporting the author. The essay “Barry,” which narrates a traumatic sexual encounter that Dunham struggles to classify as rape, raised another point of controversy. Some have questioned the veracity of the story, claiming there was no person by the name of Barry at Dunham’s college during the years she was there.

Other criticism Not That Kind of Girl has received includes the lack of diversity depicted, a lack that critics have also recognized in her HBO show “Girls.” The book contains little to no mention of minorities or of people whose racial, cultural, and economic background is different from Dunham’s. Here is where the book’s genre works both for and against the author. As nonfiction, Not That Kind of Girl, by definition, should be based on facts and actual experiences. Dunham cannot be held accountable if the society she grew up in was homogeneous—that is a structural issue. The genre of the text shields her from such criticism, given that the lack of variety in the book may reflect societal segregation rather than personal bias. At the same time, the genre facilitates the blurring of author and narrator, and the sexual abuse accusations might have had larger repercussions because of it. A creative autobiography is precisely that—creative. Dunham herself discloses “[she is] an unreliable narrator,” making it impossible to determine if she chose to exclude minorities because of prejudice, if she sexually abused her sister, or if she invented a story about her rape (51). Most importantly, however, this criticism attacks the author as a person, not her work. Whether or not we choose to take Not That Kind of Girl at face value, it is essential to remember that the book is a literary work and that we must judge it as such; it is not necessarily a reflection of the author’s character.

Other criticism Not That Kind of Girl has received includes the lack of diversity depicted, a lack that critics have also recognized in her HBO show “Girls.” The book contains little to no mention of minorities or of people whose racial, cultural, and economic background is different from Dunham’s. Here is where the book’s genre works both for and against the author. As nonfiction, Not That Kind of Girl, by definition, should be based on facts and actual experiences. Dunham cannot be held accountable if the society she grew up in was homogeneous—that is a structural issue. The genre of the text shields her from such criticism, given that the lack of variety in the book may reflect societal segregation rather than personal bias. At the same time, the genre facilitates the blurring of author and narrator, and the sexual abuse accusations might have had larger repercussions because of it. A creative autobiography is precisely that—creative. Dunham herself discloses “[she is] an unreliable narrator,” making it impossible to determine if she chose to exclude minorities because of prejudice, if she sexually abused her sister, or if she invented a story about her rape (51). Most importantly, however, this criticism attacks the author as a person, not her work. Whether or not we choose to take Not That Kind of Girl at face value, it is essential to remember that the book is a literary work and that we must judge it as such; it is not necessarily a reflection of the author’s character.

The various experiences Dunham narrates, although disconnected, guarantee laughter through their lighthearted engagement with sexuality. The “maybe” that she repeats in the introduction while wondering whether a woman is made or born resonates as the collection ultimately fails to successfully answer the question. The prevalent purpose of the book seems to be merely to amuse. Thus, unpretentious about its purpose or use of language, Not That Kind of Girl delivers exactly what it promises—a funny, one-time read.

Posted: December 8, 2014 at 5:44 pm