On Man, Beliefs and Change

El hombre: fe y transformación

John Gray

¿As human beings, what can we do to transform the world? Whatever human beings do changes the world. The question is whether projects which are formulated to change the world in certain, specific ways can succeed. And one of the problems here, of course, is that there is no “we”. Who is “we”? I mean, human speech is composed of billions of separate individuals with different goals, different plans, different values and different ideals. And yes, they can also change the world, but not in the way that they anticipate.

And do you think we can change the “we”?

The “we” changes all the time, but there never has been and there will never be a universal “we”. Because human beings, although they have many things in common, have conflicting goals. So there can’t be a “we” which has the same purposes, because even in a single individual, purposes have various conflicts with each other.

You are famous for criticizing beliefs. What do you believe in yourself?

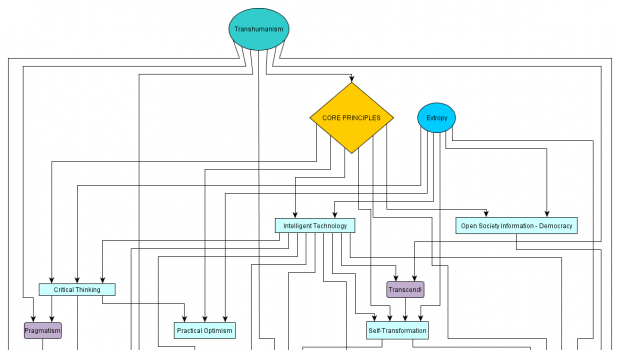

I try to avoid beliefs. We need to have beliefs in contexts such as medicine or criminal law. We try to get the best beliefs we can, based on the evidence. We all have beliefs about factual states of the world, and we even have general views of what human beings are like and what human history is developing; but I think that the dependency on beliefs, the idea that a set of beliefs or a system of beliefs can somehow provide meaning to human life, is a mistake. So I think we should economize on beliefs and have as few as possible. Make that as simple as possible and as few as possible. And the ones that we do have, when they concern manners of fact in the world–when they concern politics, for example–we should be ready to surrender them when the world changes. So I think one of the great errors of the last two or three hundred years is to formulate a system of political beliefs which is not revisable by experience, so that if you have a project you just call it Universal Democracy, or European Project, and that doesn’t work out. Rather than revising their beliefs about the project, what people tend to do is say, “well, we try twice as hard,” or “we change the circumstances for more enthusiasm or more commitment,” or “if there is a larger ‘we’ or a more harmonious ‘we’, we can achieve it.” That is always an illusion. It would be better to revise the beliefs.

So, during your lifetime, have you given up on beliefs?

No, because I didn’t have any to start off with. For me, politics is a series of temporary remedies for recurring human evils. Politics doesn’t consist of a system of universal principles or any kind of universal project. It is simply a series of temporary, provisional, partial remedies for recurring difficulties or evil. So, I believe factualism was necessary in the late seventies, eighties or nineties, but it lasted 30 years. It achieved some useful goals, but it is no longer workable. We need something different. That is normal. But one of the problems of late 20th century and even 21st century thinking about politics is that there is an assumption that there is a single project or a single strategy or a single set of responses that can always work: universal democracy, human rights, the European Project, or something of that kind. All of this should be seen as temporary experience for diminishing or reducing human evils such as poverty, torture, persecution or genocide. There are different ways of stopping or reducing these evils and if you are fixated on one, you will normally end, sooner or later, in failure.

¿Como seres humanos, qué podemos hacer para cambiar el mundo?

Lo que sea que hagan los seres humanos cambia el mundo. La interrogante es si los proyectos formulados para modificarlo de cierta manera específica pueden tener éxito. Uno de los problemas aquí es, por supuesto, que no existe un “nosotros”. ¿Quién es ese “nosotros”? El discurso humano está compuesto por miles de millones de individuos separados por sus objetivos, planes, valores e ideales diferentes. Y sí, también pueden cambiar el mundo, pero no de manera que puedan preverlo.

¿Crees que podemos cambiar ese “nosotros”?

Cambia todo el tiempo, aunque nunca ha existido y nunca habrá un “nosotros” universal. Pese a lo mucho en común, la humanidad vive objetivos contradictorios. No puede haber un “nosotros” con idénticos propósitos porque, incluso en una sola persona, sus anhelos entran en conflicto con los demás.

Eres famoso por criticar las creencias. ¿Cuáles conservas para ti mismo?

Trato de evitarlas. Necesitamos creencias en contextos como la medicina o el derecho penal. Las procuramos lo mejor que podemos basados en evidencias. Todos tenemos ideas sobre hechos concretos del mundo y, aún, puntos de vista generales sobre la humanidad y el desarrollo de la historia. Pero depender de ello, es decir, de la idea de que un conjunto de creencias o un sistema respectivo pueden darle sentido a la humanidad es un error. Así que creo que debemos economizar en creencias y tener tan pocas como sea posible. Y las que tenemos, cuando conciernen a formas de hecho en el mundo –a la política, por ejemplo– deberíamos estar listos para replantearlas si el mundo cambia. Por tanto, pienso que uno de los grandes errores en los pasados doscientos o trescientos años ha sido formular un sistema de creencias que no es verificable en la experiencia, de modo que hoy tenemos un proyecto de Democracia Universal o el Proyecto Europeo que no funcionan. En lugar de revisar sus creencias acerca de dicho proyecto, la gente prefiere decir: “Tratemos otra vez pero con más empeño”, “Modifiquemos las circunstancias en favor de un entusiasmo y compromiso mayores” o “Si hay un ‘nosotros’ más amplio y armonioso podremos lograrlo”. Eso siempre es una ilusión.

¿Durante toda tu vida has renunciado a creer?

No, porque no he tenido ninguna “creencia” desde el inicio. La política para mí es un conjunto de remedios temporales para males humanos recurrentes. La política no es un sistema de principios universales o cualquier otro tipo de proyecto universal. Simplemente es una serie de remedios parciales, provisionales y temporales. Pienso entonces que cierto factualismo fue necesario hacia finales de los años setenta, también en los ochenta y noventa. Pero ya duró más de 30 años. Hoy necesitamos algo diferente. Y es normal. Sin embargo, al pensar en la política uno de los problemas de finales del siglo XX y aún del siglo XXI es la suposición de que existe un solo proyecto, una sola estrategia o un conjunto único de respuestas con el que se puede trabajar en todo momento: la democracia universal, los derechos humanos, el Proyecto Europeo o algo por el estilo. Todo ello debería considerarse más bien como experiencias temporales para disminuir o reducir males humanos como la pobreza, la tortura, las persecución o el genocidio. Existen diferentes maneras de remediar o limitar dichos males y, si estás comprometido sólo con uno, tarde o temprano terminarás en el fracaso. [Traducción de D.M.P.]