Translated by Jessie Mendez Sayer

A few years ago, when I was in Tijuana for a conference, some colleagues from El Colegio de la Frontera Norte took us to see some of the city’s places of interest, including a couple of sectors of the famous border wall. I should mention before continuing that I had always felt a certain admiration for Tijuana’s air of bravura. I was surprised to pick up on a sense of freedom (or at least of existentialism) in the midst of that funnel-city, which leans against the border wall with roguish self-assurance, cigarette in hand. Even the famous wall brought to mind images that were somewhat unexpected.

The border wall in this area is actually a double barricade with a road running between them, where towers with migrant-detecting sensors loom, and along which the U.S. Border Patrol SUVs make their rounds. The barricade we could refer to as “interior” (meaning the one entirely within the United States, which does not directly skirt Mexico, but was instead designed as a second obstacle for anyone who has dared to cross the first wall) is tall, made of wire mesh, topped with barbed wire, and is absolutely impassable. The “exterior” wall, that is to say the one that actually does border with Mexico and can be touched by any passing pedestrian, varies in appearance and materials depending on the stretch in question.

The “exterior” barrier of the section that runs along the beach and into the sea is made of iron piling, the spaces between the piles big enough to allow an unimpeded view from one side of the border to the other. Its architectural design is much less violent than that of the solid wall, which not only blocks the vision and passage of undocumented people but also those of squirrels, rabbits, and lizards, all of which exist in less touristic areas.

The wall on Tijuana’s beach is covered in all kinds of graffiti: Christian, anti-imperialist, philosophical, romantic, et cetera. Much of this graffiti is in English, and was written by U.S. citizens who live in Mexico or who perhaps pass through Tijuana and feel outrage about their own country’s policies. The phrase in graffiti which I liked the most says: “Please don’t feed the gringos.” The image, a wonderful one, inverts the meaning of the wall. It is U.S. citizens, and not the supposed southern barbarians, who are the caged animals under observation, like those in a zoo. But it struck me that this graffiti went further than simply pointing out how U.S. immigration policy lacks humanity. Given its location, on a border wall with a view through it to the pristine fields on the U.S. side (and the port of San Diego in the distance), the graffiti made me think of Americans (and those who, like me, live in the United States) as domesticated animals.

This is Friedrich Nietzsche’s own image of modern man as a pet, properly fed, properly groomed, properly neutered, and properly broken. “Don’t feed the gringos,” they already have food; it’s in a plastic bowl in the kitchen. Order in the United States and disorder in Tijuana are presented here like the boundary between the domesticated human and the (somewhat) wild one.

The border wall in this area is actually a double barricade with a road running between them, where towers with migrant-detecting sensors loom.

This same image struck me once again a few kilometers ahead, at the part of the wall that flanks the Libertad neighborhood. Before they built the border walls (in the eighties), this was a place where dozens of migrants would cross every night. As it turned out, our driver and guide had crossed there twice, around twenty-five years ago, and he told us about his experiences with the pleasure of someone recounting an adventure: he had no regrets.

In those days, market stalls were set up every afternoon all the way along the Mexican side, so that those making the crossing could buy some juice or a couple of quesadillas while they negotiated with the smugglers, who ambled around the area like street vendors. “I have fifty pesos (dollars), will you get me across?”

“O.K.”

Back then, the smugglers would send some “bait” ahead of them, a small group of local guys (drug addicts or alcoholics, for example) so that the border police would jump on them. The border force at the time was made up of only two or three patrols for all those people. And as soon as they went for the bait, a group of ten or fifteen migrants would head across with their smuggler, running toward the gullies to hide amongst the hills behind San Diego.

Our guide told us all of this with evident joy, and it was then that another image came to me: the border as an episode of Tom and Jerry. And I realized that this image had a connection to “Please don’t feed the gringos”: in this case, the U.S. citizen is revealed to be a domestic animal (Tom the cat), and the Mexican as a smaller animal, but one that remains in a state of freedom, who does not answer to any master. It occurred to me that the origin of the wall lies in Tom’s damaged pride in the face of Jerry’s cunning and the invisible repression of his master’s law. The poor little frustrated cat went to buy a double barricade from the ACME corporation, the whole package including towers with motion sensors, so that the mice would stop making a fool out of him. Mission impossible.

The Origin of the “Bad Hombre”

At this stage, we all know that in an English accent “bad hombres” is pronounced “bad jambris,” but what exactly does it mean? Does it matter that the president of the United States uses it instead of saying, for example, “bad men,” all in English? What are the uses of anglicized Spanish, and what clues can they offer us about the representation of the Mexican in Trump’s era?

Our guide told us all of this with evident joy, and it was then that another image came to me: the border as an episode of Tom and Jerry.

Before answering these questions, it is worth noting that the use of Spanish terms with anglicized pronunciation is now a common part of the English language, and that they are used by characters as cherished as Bart Simpson (“Ay, Caramba!,” pronounced with the English “r”). I also fondly remember a conversation between Elaine and Seinfeld while eating ice cream, when Elaine says (in anglicized Spanish) “Qué rico!,” and Seinfeld knowingly replies “Suave!” And of course, there is also Arnold Schwarzenegger’s immortal phrase, “Hasta la vista, baby!,” which nobody in their right mind would want to remove from the English language.

We therefore must proceed with caution, in order to avoid a “politically correct” critique that measures everything by the same yardstick. Twenty years ago, the linguist Jane Hill published a series of studies about the so-called mock Spanish, which Hill defines as a “jocular register of English” that uses elements that English speakers consider to be Spanish in order to create a light-hearted or humorous effect. Based on a detailed study, Hill concludes that mock Spanish “reproduces racist stereotypes of Spanish speakers,” although, she adds, English speakers usually deny that its use has any racist undertones.

I do not wish to argue with Hill about how racist any particular colloquial turn of phrase may or may not be; mock Spanish is used far too frequently and in many forms. Having seen several seasons of the show, I am certain that the writers of The Simpsons, for example, feel a certain affinity toward Mexicans. In fact, “reinforcing racial stereotypes” doesn’t necessarily imply any antipathy for the group of humans in question; you can reinforce a racial stereotype in order to transcend it, or its use can be ambiguous.

To offer up a Mexican example, the song “Negrito sandía,” or “Black Boy Watermelon,” by Cri Cri, undoubtedly reinforces racial stereotypes (it’s about “a black boy with an angel face” who “turned out to be more foul-mouthed than a parrot from the slums”). Furthermore, the association of the Black person with a watermelon is a classic element of white racism toward Black people: in the United States, watermelon was a luxury for freed slaves, and so the image of a watermelon came to be used with racist malice, like a sign of the supposedly insurmountable distance between blacks and whites (the champions of racial segregation chose different symbols of luxury for themselves, unattainable for black people). In other words, Cri Cri’s song reproduces racist stereotypes. There is no doubt about it. However, this does not necessarily mean that when Francisco Gabilondo Soler (Cri Cri) composed the song in the early forties, he did so to propagate Black people’s social inferiority, nor that he did so as a gesture of hate. This idea would come later.

What are the uses of anglicized Spanish, and what clues can they offer us about the representation of the Mexican in Trump’s era?

In the same way, the “ay, caramba!,” the “hasta la vista!,” and the “suave!” uttered by Bart, the Terminator, or Seinfeld could propagate racial stereotypes and yet also signal affinity toward or solidarity with Mexicans or Hispanics. This idea would also come later. In any case, regardless of whether racism comes into play, it is important to understand that when we consider the use of mock Spanish, we draw near to the racial border that divides the Mexican and the Anglo. It could be said that whoever utters the phrase is playing with this border, sometimes crossing it in a friendly manner, and other times reinforcing it.

Right. So now we can move on to the topic of the “bad hombre.” What does this expression mean? Does it have similar historical baggage, so to speak, as the watermelon in the history of racism against Black people? Should Mexicans let slide the fact that the U.S. president refers to the Mexican criminal component using this term, and not be offended? The expression “bad hombre” was common in western movies during Hollywood’s early decades. There is even a movie called Hombre, starring Paul Newman (1967), where the “bad hombre” (Newman) is a white man who has been raised by Apaches, and who goes on to confront discrimination in the white world. In old westerns, the figure of the “bad hombre” is actually part of the landscape, part of the fauna of the West. Usually the “bad hombre” hides behind rocks or thickets, getting up to no good, and must be exterminated by sheriffs and colonials. The “bad hombre” prowls. He is never a farmer, and certainly never a landowner. In the oldest westerns, the sheriffs also referred to the “bad hombres” using the term varmint, alluding to the wild animals that sometimes ate a part of the harvest, or ate chickens. A “bad hombre” is, therefore, like a coyote lying in wait, and must be kept outside of the perimeter of civilization.

The image of the Mexican migrant as a category infiltrated and irreparably contaminated by “bad hombres” who are on the prowl and must be eliminated is therefore loaded with all the brutality of the colonization of the American West. It is the violence of the colony against the former inhabitant, rootless and dispossessed and transformed into a livestock thief. Does Trump’s use of this expression reinforce Mexican racial stereotypes? Yes, without a doubt. Is it also an expression of racial antagonism? Again, yes.

_

The Importance of the Wall

Let’s build that wall! This was Donald Trump’s most popular campaign slogan, but what does it mean? Would it make a difference if the United States were to invest in a building project of this kind?

The image of the Mexican migrant as a category infiltrated and irreparably contaminated by “bad hombres” who are on the prowl and must be eliminated is therefore loaded with all the brutality of the colonization of the American West.

A consensus is beginning to form in Mexico, at least on an informal level, that the wall project is in a way irrelevant. Chihuahua Cement, a Mexican company, has even put itself forward as a provider. You want a wall? We’ll build it for you! There are even people who think that building it would benefit Mexico. Are they right?

After all, it is true that a wall already exists. The wall is not new. The United States has been investing in reinforcing its border with Mexico since 1994, and today around 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) of the border is fenced or walled. This cost around $7 billion, as well as what it costs to maintain it. Extrapolating from this figure, building a wall along the roughly 2,300 remaining kilometers (1,429 miles) would cost around $15 billion, more or less, plus maintenance, without taking into account the cost of lawsuits for violating environmental agreements, or the purchase of land in cases of owners who are reluctant for anything to be built on their property, or the compensation that would have to be paid to the ethnic group Tohono O’odham Nation, whose territory sits on both sides of the international border.

In addition, the United States has invested heavily in increasing police patrols along the border. In 1994, “la migra” (Border Patrol) had 4,100 agents, and by 2015 it had almost reached 21,100. So, has the combination of a fivefold increase in the Border Patrol force and the thousand kilometers of existing wall failed to seal the border? Let’s see.

In 2015 the number of migrants caught at the border was just over 337,000 (230,000 were Mexicans), a figure close to 1970s levels, and far fewer than the 1.6 million border arrests made toward the end of the nineties. Besides, for reasons that are demographic as much as labor-related, the flow of Mexican migrants to the United States has been in negative figures since 2009, and has been close to zero since 2005. Lastly, there is the fact that the majority of the undocumented migrants who enter the United States do not do so by crossing the border with Mexico, but via airports and with tourist visas. In 2015, Border Patrol captured, as already mentioned, 337,000 migrants who crossed the border without papers, but they caught 527,000 undocumented migrants who had entered legally with tourist visas.

For all these reasons, there are those in Mexico who argue that if the United States builds a border wall it will not affect Mexico all that much. The great Mexican migration to the United States is basically over, and so this wall would only serve as a political concession to Trump’s support base, who would like to see migration used as a scapegoat. The wall would therefore be a colossal ritual of expense, carried out in order to allay fears that in fact have other causes, such as automation, for example. There are even those who speculate that a wall like this one would somehow benefit Mexico (beyond Chihuahua Cement): the wall and the current Border Patrol forces migrants to cross via difficult and dangerous routes, which has allowed Los Zetas and other criminal groups of this kind to control the flow of migrants. According to official figures, over 6,500 migrants have died crossing the border into the United States since 1998. There are also many thousands of Central Americans who have died while crossing Mexico’s southern border; some estimate dozens of thousands. Furthermore, according to the CNDH (National Commission for Human Rights), in 2012 around 11,000 Central American migrants were kidnapped and suffered extortion by Mexican traffickers. Perhaps a completely sealed northern border would reduce the number of people using Mexico as a point of transit, and therefore reduce some of these figures. These are some of the speculative ideas circulating these days (always look on the bright side).

The wall is not new. The United States has been investing in reinforcing its border with Mexico since 1994, and today around 1,000 kilometers of the border is fenced or walled.

There is no question that adding another 2,000 kilometers to the wall that already exists between Mexico and the United States would be a bad use of public funds. Dr. Everard Meade, director of the University of San Diego’s Trans-Border Institute, has asserted that the resources invested in the wall would have a far more positive effect on the United States’ economy if they invested it instead in improving the quality of the roads and entry points along the border with Mexico, which currently resemble chicken coops. This would also have an important political and symbolic effect. He is right.

To spend another $15 billion on a wall, and billions more on its maintenance, would be to invest heavily in the United States’ cultural and political isolation, and would also be a considerable investment in the portrayal of Mexico as a barbaric land, along with all the consequences that could follow. Just like the great ice wall on the television series Game of Thrones, this would serve to harden the relationship between the supposed civilization and the supposed barbarians.

In an equation such as this, the risk to the United States would not be insignificant. Just remember the border wall in Tijuana: “Please don’t feed the gringos.”

.

From Let’s Talk about Your Wall: Mexican Writers Respond to the Immigration Crisis, edited by Carmen Boullosa and Alberto Quintero. Used with the permission of The New Press. Copyright © 2020 by Claudio Lomnitz.

- La primera versión de este texto fue publicado en tres diferentes artículos. “Please don’t feed the gringos” y “Genealogía del ‘Bad Hombre’” aparecieron en La Jornada en 2013 y 2017 respectivamente; “La importancia del muro” se publicó en Nexos en 2017.

-

Jane H. Hill, “Intertextuality as Source and Evidence for Indirect Indexical Meanings”. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 15(1): 113-124.

*Image by Chad Zuber

_

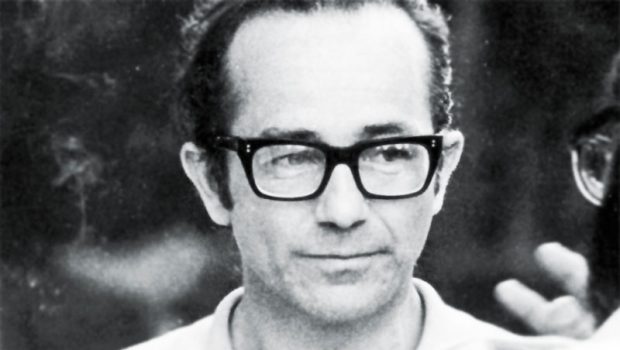

Claudio Lomnitz is the Campbell Family Professor of Anthropology at Columbia University. He’s the author of several books, all set in Mexico, including Death and the Idea of Mexico and The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón. In addition to his academic publications, Lomnitz is a regular contributor to the Mexican media. He writes a bi-weekly column for the newspaper La Jornada and a monthly column for Nexos. In 2010, he was awarded Mexico’s National Drama Award for his play El verdadero Bulnes, which he wrote with his brother, Alberto Lomnitz. Their most recent play is the musical La Gran Familia, which opened the 2018 Festival Internacional Cervantino, in Guanajuato, Mexico, with Mexico’s National Theater Company. Claudio Lomnitz’s most recent book, Our America, is a reflection on exile and transculturation that moves between Eastern European and South American history, by way of the story of his grandparents, and will appear in the spring of 2021, with Other Press.

Claudio Lomnitz is the Campbell Family Professor of Anthropology at Columbia University. He’s the author of several books, all set in Mexico, including Death and the Idea of Mexico and The Return of Comrade Ricardo Flores Magón. In addition to his academic publications, Lomnitz is a regular contributor to the Mexican media. He writes a bi-weekly column for the newspaper La Jornada and a monthly column for Nexos. In 2010, he was awarded Mexico’s National Drama Award for his play El verdadero Bulnes, which he wrote with his brother, Alberto Lomnitz. Their most recent play is the musical La Gran Familia, which opened the 2018 Festival Internacional Cervantino, in Guanajuato, Mexico, with Mexico’s National Theater Company. Claudio Lomnitz’s most recent book, Our America, is a reflection on exile and transculturation that moves between Eastern European and South American history, by way of the story of his grandparents, and will appear in the spring of 2021, with Other Press.©Literal Publishing

Hace un par de años estuve en Tijuana en una conferencia, y los colegas de El Colegio de la Frontera Norte nos llevaron a visitar algunos puntos de interés en la ciudad, incluyendo un par de sectores de la famosa barda fronteriza. Aclaro, antes de comenzar, que sentí cierta atracción por el desparpajo tijuanense. Me sorprendí de sentir un aire de libertad –o al menos de existencialismo– en medio de aquella ciudad-embudo, que se recarga en la barda fronteriza con el desenfado de un truhán, fumándose un cigarrito. Incluso la famosa barda me trajo imágenes algo inesperadas.

El muro fronterizo en este sector es en realidad una doble barda, con una carretera entre las vallas, donde hay unas torres altísimas con sensores para detectar migrantes, y se pasean las camionetas de la Border Patrol. La barda que podríamos llamar “interior” (o sea la que está enteramente en el lado estadunidense, que no colinda con México, sino que está diseñada para ser un segundo obstáculo para quien se haya animado a librar la primera barda) es alta, de malla, con alambres de púa arriba, y de plano infranqueable. La barda “exterior”, es decir, la que da a México y que puede ser tocada por cualquier peatón, va cambiando de aspecto y de materiales según el tramo.

En el sector de la playa y adentro del mar, esta barda ‘exterior’ está hecha de pilotes de hierro, con espacios entre uno y otro, que permiten que la mirada se pasee sin problema de un lado a otro de la frontera—se trata de una arquitectura un poco menos violenta que la de la barda sólida, que tapa la vista y el paso no sólo a los indocumentados, sino también a ardillas, conejos o lagartijas, y que hay en partes menos turísticas.

La valla de la playa de Tijuana está llena de pintas de todo tipo –cristianas, antimperialistas, filosóficas, amorosas, etcétera–. Muchas de esas pintas están en inglés, y fueron escritas por estadunidenses que viven en México o bien que van a Tijuana de paseo y se indignan por la política de su propio país. Una de esas pintas, que fue la que más me gustó, dice: “Please don’t feed the gringos”. La imagen, buenísima, invierte el sentido de la barda –los animales observados y enjaulados, como de zoológico, serían ahora los estadunidenses, y no los supuestos bárbaros del sur–. Pero me pareció que la pinta calaba todavía más hondo que el simple señalamiento de la falta de humanidad de la política migratoria estadunidense. Puesta donde estaba, en una barda fronteriza con vista a los campos impecables del lado estadunidense (y el puerto de San Diego a la distancia), la pinta me hizo pensar en los estadunidenses (y en quienes, como yo, vivimos en Estados Unidos) como animales domesticados.

Es la propia imagen de Nietzsche del hombre moderno como una mascota, bien alimentada, bien peinada, bien capada, y bien desgarrada. “Don’t feed the gringos”, que ya tienen su alimento en un plato de plástico en la cocina. El orden estadunidense y el desorden tijuanense aparecen, aquí, como una frontera entre el humano domesticado y el humano (un poquitín) más salvaje.

Esta misma imagen me volvió a asaltar unos kilómetros más adelante, en el tramo de barda que colinda con la colonia Libertad. Antes de que se construyeran las bardas fronterizas –en los años ochenta– era ese un punto de cruce por el que pasaban docenas de migrantes cada noche. Resultó que el chofer que nos guiaba había cruzado dos veces por ese punto, hacía como 25 años, y nos contó sus experiencias con el disfrute de quien narra una aventura: lo bailado, ya nadie se lo quita.

En ese tiempo se ponía un tianguis por la tarde a todo lo largo del lado mexicano, para que cada noche los cruzantes se compraran su jugo o unas quesadillas en lo que negociaban con los polleros, que se paseaban por el punto como vendedores ambulantes:

“Traigo cincuenta pesos (dólares), ¿me cruzas?”

“Va.”

Entonces los polleros mandaban por delante, como “carnada”, un pequeño grupo de muchachos locales –drogadictos o alcohólicos, por ejemplo– para que les cayera la migra. La migra entonces tenía sólo dos o tres patrullas para toda esa gente. Y en cuanto se movilizaba hacia “la carnada”, salía un grupo de 10 o 15 migrantes con su pollero, corriendo hacia las barrancas para internarse en los cerros de atrás de San Diego.

Nuestro guía nos contaba todo aquello con visible alegría, y fue entonces que me vino una segunda imagen: la frontera como un episodio de Tom y Jerry. Y me di cuenta de que la imagen se relaciona con la de “don’t feed the gringos”: en este caso el estadunidense queda expuesto como una mascota doméstica (el gato Tom), y el mexicano como un animal más pequeñito, pero todavía en estado libre, que no tiene que responder a su dueño. Se me ocurrió que el origen de la barda está en el orgullo mancillado del gato Tom ante la astucia del ratón Jerry y ante la represión invisible de la ley de su amo. El pobre gatito frustrado se fue a comprar una doble barda marca ACME, con todo y torres con sensores, para que ya no lo burlen los ratones. Una misión imposible.

Genealogía del “Bad Hombre”

A estas alturas todos sabemos que la voz inglesa “ bad hombres” se pronuncia “bad jambris”, pero bien a bien ¿qué significa la expresión? ¿Importa que el presidente de Estados Unidos la utilice en lugar de decir, por ejemplo, “ bad men”, todo corrido en inglés? ¿Cuáles son los usos del español anglicado y qué pistas nos dan sobre la representación de lo mexicano en tiempos de Trump?

Antes de responder a estas preguntas, vale la pena hacer notar que el uso de términos españoles en pronunciación anglicada es ya parte corriente del habla inglesa, y que personajes tan queridos como Bart Simpson los utilizan (¡Ay, caramba!, pronunciado con “erre” inglesa). Recuerdo también con cariño un diálogo entre Elaine y Seinfeld comiendo helados, donde Elaine dice (en español anglicado): “¡Qué rico!”, y Seinfeld contesta, significativamente: “¡Suave!” Y claro, está también la inmortal frase de “¡Hasta la vista, baby!” de Arnold Schwarzenegger, que nadie en su sano juicio querría extirpar de la lengua inglesa.

De modo que nuestra reflexión debe proceder cuidadosamente, para evitar una censura “políticamente correcta” que mida todo con el mismo rasero. Hace unos 20 años la lingüista Jane Hill publicó una serie de estudios acerca del llamado mock Spanish, que se puede traducir como “español de guasa”, y que Hill define como “un subregistro coloquial del inglés” que utiliza elementos que los angloparlantes consideran son del español para generar interacciones livianas o cómicas. A partir de un estudio detallado, Hill concluye que el mock Spanish “reproduce los estereotipos raciales de los hispanoparlantes”, aunque, agrega, los angloparlantes suelen negar que su uso tenga trasfondo racista.

No quisiera discutir con Hill respecto de cuán racista puede o no ser tal o cual giro coloquial; el español de guasa se usa demasiado frecuentemente y de formas muy variadas. Habiendo visto varias temporadas del programa, me queda claro que los escritores de Los Simpson, por ejemplo, sentían simpatía por los mexicanos. De hecho, “reforzar estereotipos raciales” no necesariamente implica antipatía hacia el grupo humano de referencia; se puede reforzar un estereotipo para trascenderlo, o puede haber ambigüedad en el caso.

Por poner un ejemplo mexicano, la canción Negrito sandía, de Cri-Cri, indiscutiblemente refuerza estereotipos raciales (trata de “un negrito con cara angelical” que “salió más deslenguado que un perico de arrabal”). Además, la asociación del negro con la sandía es un elemento clásico del racismo blanco contra los negros: en Estados Unidos la sandía era el lujo de los esclavos libertos, y la imagen de la sandía fue entonces usada con saña racista, como signo de la distancia supuestamente infranqueable entre blancos y negros (los campeones de la segregación racial escogerían para sí otros signos de lujo, inalcanzables para los negros). En otras palabras, la canción de Cri-Cri “reproduce estereotipos raciales”. No hay duda de eso. Sin embargo, eso no significa necesariamente que cuando Francisco Gabilondo Soler, Cri-Cri, compuso la canción, a inicios de los años cuarenta, lo haya hecho ni para reproducir la inferioridad social de los negros, ni como signo de odio. Eso estaría por verse.

Del mismo modo, los “¡ay, carambas!”, los “¡hasta la vista!” y los “¡suave!” proferidos por Bart, el Terminator o Seinfeld pueden reproducir estereotipos raciales y, sin embargo, marcar simpatía o solidaridad con los mexicanos o “hispanos”. También estaría por verse. Como sea, independientemente de si hay o no racismo en el caso, vale la pena entender que cuando está uno ante el uso del “español de guasa”, está uno también cerca de la frontera racial entre lo mexicano y lo anglo. Podríamos decir que el que emite la frase está jugando con esa frontera, unas veces para franquearla amistosamente, otras para reforzarla. Bien. Pasemos al asunto del “ bad hombre”. ¿Qué significa esta expresión? ¿Tiene un bagaje histórico parecido, digamos, al de la sandía en la historia del racismo contra los negros? ¿Los mexicanos deben dejar pasar el hecho de que el presidente estadunidense se refiera al elemento criminal mexicano con ese término sin ofenderse? La expresión “bad hombre” es común en las películas vaqueras de las primeras décadas de Hollywood. Incluso hay una película titulada Hombre, con Paul Newman (1967), donde el “ bad hombre” (Newman) es un hombre blanco que ha sido criado por los apaches, y que luego enfrenta la discriminación del mundo blanco. En los viejos westerns la figura del bad hombre es en realidad parte del paisaje, parte de la fauna del oeste. Usualmente el “ bad hombre” se oculta tras de piedra o matorral para hacer fechorías, y debe ser exterminado por cherifes y colonos. El “ bad hombre” merodea. No es nunca un agricultor, ni mucho menos un propietario. En los westerns más antiguos los cherifes se referían también a los “ bad hombres” con el término varmint, que alude a animales salvajes que se pueden comer parte de la siembra, o robar gallinas. Un “bad hombre” es, entonces, como un coyote que acecha, y que hay que mantener fuera del perímetro de la civilización.

La imagen del migrante mexicano como una categoría infiltrada y contaminada irreparablemente por “bad hombres”, que acechan y deben ser eliminados, viene entonces cargada de toda la ferocidad de la colonización del oeste estadunidense. Es la violencia del colono contra el antiguo poblador, desarraigado y desposeído y transformado en cuatrero. ¿La expresión de Trump refuerza estereotipos raciales del mexicano? Sí, sin duda. ¿Es, además, una expresión de antagonismo racial? Sí, también.

La importancia del muro

¡Construyamos ese muro! Ese fue el lema de campaña más atractivo de Donald Trump, pero ¿qué significa? ¿Importaría que los Estados Unidos invirtieran en un proyecto de obra como este?

En México comienza a haber algo de consenso, a nivel informal al menos, en el sentido de que el muro como proyecto tiene algo de irrelevante. Cementos Chihuahua incluso se ha ofrecido como proveedor. ¿Quieren un muro? ¡Construyámoslo! Incluso hay quienes piensan que una obra así podría beneficiar a México. ¿Tienen razón?

Finalmente, es verdad que existe ya un muro. Que lo del muro no es novedad. Desde 1994 los Estados Unidos han invertido en sellar su frontera con México, y hoy alrededor de mil kilómetros de frontera están bardeados. Esa obra costó alrededor de siete mil millones de dólares, amén de lo que cuesta anualmente en manutención. Si extrapolamos a partir de esa cifra, construir un muro sobre los alrededor de dos mil 300 kilómetros faltantes costará unos 15 mil millones de dólares, más o menos, además del mantenimiento, y sin estimar costos por demandas judiciales por violaciones a tratados ambientales, o adquisición de predios en casos de dueños renuentes a que se construya en sus terrenos, o las compensaciones que habría que pagarle a la etnia tohono o’odham, cuyo territorio atraviesa la frontera internacional.

Además, los estadunidenses han invertido enormemente en aumentar el patrullaje de la frontera. En 1994 “la migra” (la Border Patrol) tenía cuatro mil 100 agentes, en 2015 tenía ya 21 mil. ¿Acaso la combinación entre una migra quintuplicada y los mil kilómetros existentes de muro no ha sellado ya la frontera? Veamos.

En 2015 las capturas de migrantes en la frontera fueron de arribita de 337 mil (230 mil son mexicanos), una cifra parecida a los niveles de 1970, y muy por debajo del pico de arriba de 1.6 millones de aprehensiones fronterizas de fines de los años noventa. Además, por razones tanto demográficas como laborales, el flujo de migrantes mexicanos a los Estados Unidos ha estado en números negativos desde 2009, y era cercano a cero desde 2005. Por último, está el hecho de que la mayor parte de los indocumentados que ingresan a Estados Unidos no entran por la frontera con México, sino por los aeropuertos, y con visas de turista. En 2015 la migra capturó, como dijimos, a 337 mil migrantes que cruzaron la frontera sin documentos, pero pescó a 527 mil indocumentados que habían ingresado legalmente, con visas de turista.

Por todas estas razones hay quienes argumentan desde México que si los Estados Unidos construyen un muro fronterizo no afectará demasiado a México. Finalmente, la gran migración mexicana a Estados Unidos básicamente ya concluyó, y lo del muro no será sino una concesión política a las bases políticas de Trump, que quieren tener en la migración un chivo expiatorio. El muro sería entonces un gigantesco expendio ritual, hecho para sosegar miedos que en realidad tienen otras causas, como la robotización, por ejemplo. Incluso, hay quienes especulan que un muro así podría beneficiar en algo a México (más allá de Cementos Chihuahua): el muro y el patrullaje actual obliga a los migrantes a atravesar por cruces difíciles o peligrosos, cosa que ha facilitado que Los Zetas y otros criminales del estilo controlen el flujo migratorio. Según cifras oficiales, ha habido más de seis mil 500 muertos en cruces fronterizos a Estados Unidos desde 1998. Hay también muchos miles de centroamericanos que han muerto en los cruces a la frontera sur de México —algunos calculan decenas de miles—. Además, según la CNDH, en 2012 hubo alrededor 11 mil migrantes centroamericanos que habían sido secuestrados y extorsionados por traficantes en México. Quizá una frontera norte totalmente sellada reduciría el uso de México como territorio de trasiego y, con ello, disminuirían algunas de estas cifras. Son algunas de las especulaciones que circulan hoy (al mal tiempo, buena cara).

No hay duda de que agregar otros dos mil kilómetros al muro ya existente entre México y Estados Unidos sería una mala inversión de los dineros públicos de Estados Unidos. El doctor Everard Meade, director del Trans-Border Institute de la Universidad de San Diego, ha alegado que los recursos invertidos en el muro tendrían un efecto muchísimo más positivo para la economía estadunidense si se invirtieran en mejorar la calidad de las carreteras y puertos de entrada en la frontera con México, que en la actualidad parecen gallineros. Tendría, además, un efecto político y simbólico importante. Tiene razón.

Invertir otros 15 mil millones de dólares en un muro, y miles de millones más en su mantenimiento, será invertir fuertemente en el aislamiento cultural y político de Estados Unidos, y será también una magna inversión en la representación de México como tierra bárbara, con todas las consecuencias que eso pueda tener. Como en la teleserie Game of Thrones, servirá para endurecer las relaciones entre una supuesta civilización y una supuesta barbarie.

Y en una ecuación así el riesgo para Estados Unidos no será menor. En la valla fronteriza de Tijuana hay un graffiti que reza así: “Please don’t feed the gringos”.

*Del libro Let’s Talk about Your Wall: Mexican Writers Respond to the Immigration Crisis, editado por Carmen Boullosa y Alberto Quintero. Reproducido con el permiso de The New Press. Copyright © 2020 de Claudio Lomnitz.