Pondering on the Future

Pensar el futuro

Adriana Díaz Enciso

Some weeks ago, just before the omicron wave made us the gift of this pitiful déjà vu sensation as we approached the festive season, leaving us futilely trying to pluck assurance from uncertainty, I was blithely strolling around Soho.

The city was festive and colourful, with Christmas decorations glowing everywhere, the streets full of people, as if we’d gone back (notwithstanding the facemasks and ever-present sanitising gel) to an earlier and kinder time, to how things were before the pandemic came to shake us with a stroke of irrevocable reality.

I was walking aimlessly, which is one of the most pleasant ways of walking, when I suddenly found myself in Poland Street. I was glad, as always: William Blake and his wife Catherine lived there during the first years of their marriage, and it was there that the spirit of his beloved, deceased brother Robert revealed to him the printing method that he would use from then on in his illuminated books. That building doesn’t exist anymore; there is in its place a huge block of offices for rent, like a cardboard box. Across the street there’s a pub, The Kings Arms, where in 1781 the Ancient Order of the Druids was revived, and where it seems they still gather, for better or worse.

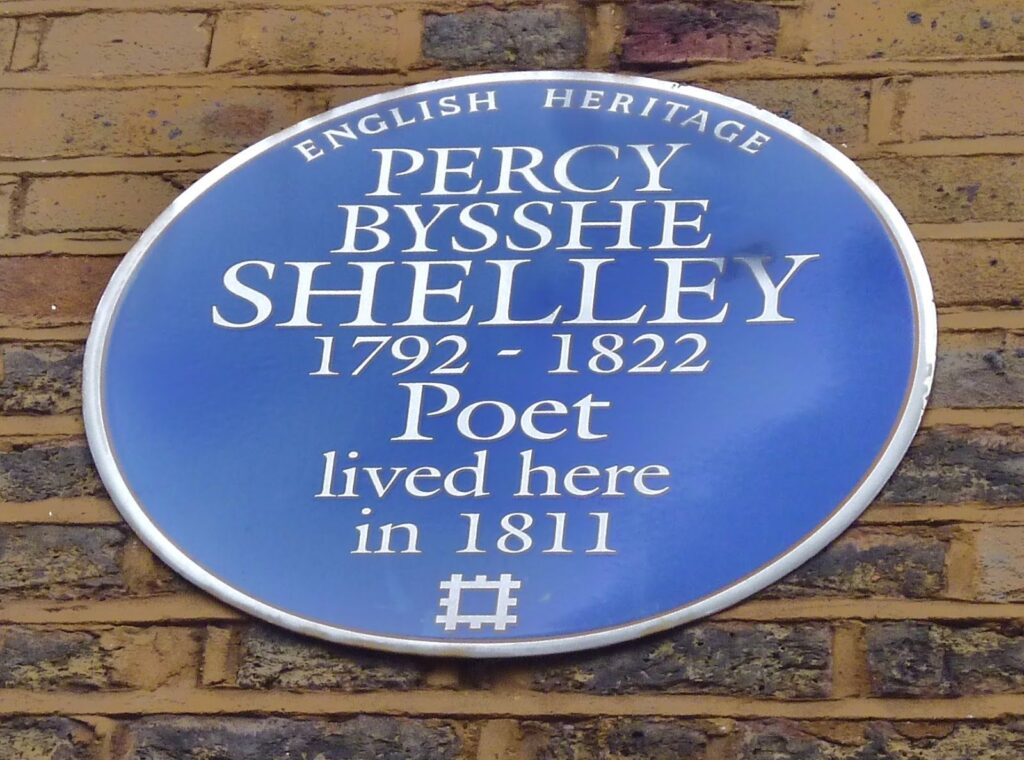

As I reached a corner I noticed an English Heritage blue plaque, according to which Percy Bysshe Shelley had lived there. Redoubled joy!

I don’t remember having seen that plaque before, but when I got back home I hurried to look it up and, indeed, in 1811 Shelley and his friend Thomas Hogg took rooms in 15 Poland Street, after being expelled from Oxford for having published The Necessity of Atheism. Though Shelley, taken by the wallpaper in their rooms, seems to have cried, “We must stay here; stay forever!”, his stay there was rather brief.

Recently I gave an online talk for the National Autonomous University of Mexico about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and its origins in the famous (and thoroughly intense) gathering at Villa Diodati, near Lake Geneva in Switzerland. That afternoon walking around Soho, I was still immersed in the tormented, incendiary and fertile world of the Shelleys, Byron and Polidori, and I was therefore most pleased to come across that trace from the poet as a greeting from a world much more distant than my own pre-pandemic one, and to know that Shelley had shared a street with Blake. What did it matter that it was in different times? Such encounters (the promise of which made me come to live in London, and stay, nearly 23 years ago, which may be a sign of madness) are not constrained by time. Blake and Shelley: an encounter. I was joining them now, and no one could show any evidence that it wasn’t so.

But how true is this romantic vision of time? That very morning I had been thinking, troubled and for the umpteenth time, about the ever more automated way in which we lead our lives. The lost time, forever irretrievable, in our computers and mobile phones; life sucked by the Internet’s black hole; the self-service checkout talking machines in so many supermarkets and their wearing cacophony; the incontinent proliferation of passwords and verification codes, and the infinite ways to store data, control our identity, accelerate progress and its spawn, and “interact” with machines, of which I know little or nothing at all, because if I knew more, I don’t know if I’d go on finding life in this world tolerable.

That afternoon, however, it was still with joy that I sat at a snug café I had just discovered. My plan was to settle there for around an hour and write. Writing in cafés has been one of the topmost pleasures in my life for nearly forty years, and one that, after Covid’s assaults, I have started to recover only recently, so the afternoon promised to be fruitful. It was ill luck that, just when I was starting to take off, I heard I had received a message in my mobile (and I must state that my phone isn’t even smart, for I am convinced that a mobile’s intelligence is directly proportional to that subtracted from its owner, whether they like it or not). I ignored the message. Less than a minute later I got another, and then a third one, and so I looked: they were from my bank. They said that they had detected a suspicious £2.40 transaction in such and such café, and that I should respond immediately to say if the offender had been me, or else they would block my card.

That’s another of the pandemic’s sequels: the fear of touching money, and the growing number of businesses which, in fact, only accept card payments. I didn’t know if I should respond. What if it was a scam, and if I answered “yes”, the real crooks gained access to my account in an incomprehensible manner, and emptied it? I then received a call; another automated message, insisting: had I purchased that bloody coffee, or not? By now furious, I called my bank. They told me that indeed, the messages were theirs. I asked them how on earth buying a coffee, spending two wretched pounds with forty pence in the city where I live can be considered a suspicious transaction. The answer was that transactions obeying that description are selected randomly, by machines, of course, to guarantee “our client’s security,” and that we ought to respond right away.

The ordeal took me half an hour. For the next thirty minutes I tried to work, though, needles to say, without much success, and my coffee had got cold. Everything had been altered; my joy had been hopelessly fragmented in that horrible way that can only be inflicted by a technology that we neither understand nor control. As if aboard a sad ship setting sail noiselessly, Blake and Shelley were moving away, with their fire and their verse.

“It’s going to fall,” I thought. One day all this will fall, no matter how much diabolical ingenuity there is, how many satellites and rubbish we’ve left floating in space, and no matter how much we depend on the unintelligible tangle. It’s going to end, simply because that is the destiny of all things, and that is a form of hope, even if I know too well that I won’t see it, nor will I ever get back the (now I can see it) happy and innocent life I remember so well prior to Internet’s takeover, with its throng of sinister siblings. Every time somebody tells me that no, technology’s empire will never end, I respond that that’s what they said about the Roman empire, and look where it is now. The hecatomb will probably start with one of those loops that are already part of our everyday life, when the super sophisticated gadgets we use start doing things that not even technicians understand anymore, making us sink in states both puerile and dreadful of impotence, anxiety, and fury. One of those loops, but gigantic. When the silent tyranny starts to fall, our poor civilisation will fall into indescribable chaos. And we will have deserved it.

Or not, for how many of us did decide that we wanted to live this way? It has been imposed on the vast majority of us. How? By whom? By that amorphous mass, “society”; by the acceptance from no identifiable leader that that’s how things are, now. By an incomprehensible collective error of judgement according to which all these novelties are necessary for our functioning and existence. By businessmen and women and unbalanced IT geniuses who divorced reality long before the rest of us.

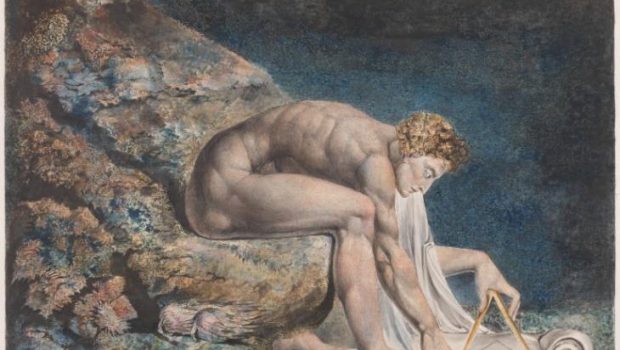

One of the reflections aroused when I was preparing my talk on Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus (1818) was that nowadays to cause an impact like that of Mary Shelley’s novel is utterly impossible. What humanity has seen since has literally freed us from fright. Just like nobody is astonished anymore by living subjugated by Blake’s current and no doubt dark Satanic Mills, we don’t bat an eyelid at the arrogance of legions of Victor Frankensteins tempting the limits of human diligence. No one is shocked anymore by the invention of one or hundreds of monstruous creatures. The opposite is rather the norm: our civilisation’s dazzling developments are celebrated by the press and in the Web’s labyrinthine echo chamber, and welcome by everyone with unquenchable enthusiasm; the mutilations, grafts, copulations and aberrations carried out day after day under the impersonal light of infinite laboratories all over the world are indiscriminately welcome, praising their service to humanity, with the same discernment that leads us now and then to make long queues to purchase Apple’s latest invention: such are our surrogate rituals.

We’re all part of it, and though the ethical questioning around these supposed or real improvements deserves each a space of serious debate, the latter is inevitably lost in the (dis)informative excess. All that is left is our meek acceptance. Plugged into a gadget on which we hang more and more “apps” until our whole life depends on it, we all are now the creature imagined by Mary Shelley, monstruous and, simultaneously, helpless victim. And to a certain extent, every time that we add another “app”, click here or there without wondering why, every time that we integrate such tricks into our individual and social life, we all are also Victor Frankenstein.

If we stop for a moment and try to think with the thoroughness which is ever harder for our fragmented attention, we can see clearly that the way we 21st Century inhabitants live is not normal; that there is no good sense at all in bartering reality for a virtual reality, and in passively accepting that every action in our life should depend on those gadgets, apps and screens that generate enormous amounts of waste, that we don’t understand, definitely do not control, that have taken our privacy away from us and are also snatching away our life. Or, at least, a human life that deserves that name.

So far are we from Mary Shelley’s lucidity that we rarely shudder when witnessing how our fellow humans visit the most beautiful places on earth, or museums and galleries exhibiting sublime works of art, without ever getting to see directly landscape, architecture, monument or art; brandishing their mobile phones, they get there heedlessly, take the picture or video and leave, without devoting an instant even of contemplation or direct contact to their experience. Zombies, automatons, we feed social media with images and videos; we plague with them whoever sits with us at a café, so that interaction with others is also tampered with, turning us away from the pleasures and risks of true conversation, while our head is filled with noise. Computer chaff. The algorithm’s concrete squalor. Stripped of contemplative and fecund solitude by our own hand, we’re left stranded in the loneliness that kills, that of sheer desolation. Are we to be surprised by the high rates of depression among us?

That the monster doesn’t frighten us collectively anymore no doubt frightens me. It makes me, indeed, depressed. It reminds me the extent to which I am a foreigner in my time. I know I’m not the only one who, lethargic and all, not knowing how to escape, is fully aware of the intrinsic perversity in our twisted love affair with technology. Fortunately, it is still possible, for instance, to walk with our own feet down Poland Street, and to encounter in a burst of imagination William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley, to abolish time for an instant and then sit at a café with the urge to write, all these undoubtedly human actions in which past generations can recognise themselves. I am grateful. I wonder, though, what resources I will have to lay my hands on to preserve enough firmness of spirit, so that a robot’s text messages in my mobile won’t sever that cardinal link with the humanity that precedes us, and the humanity to come.

On the boundary between the year gone and the one that is about to start, I am thinking of the future. The future we are creating right now, immune to horror, and the future that, with unforgivable flippancy, we’re leaving as our heritage to our youth, to children and to those who are yet to come. I am wondering why it is so hard for us to find the guts to say, “No. I do not consent to being stripped of my humanity”.

*Image by Luc Mercelis

Hace algunas de semanas, justo antes de que la oleada de ómicron nos regalara con esta lastimera sensación de déjà vu al filo de las fiestas decembrinas y nos dejara intentando inútilmente arrancar certezas de la incertidumbre, anduve paseando por Soho muy quitada de la pena.

Estaba la ciudad colorida y festiva, las decoraciones de navidad brillando por todas partes, las calles llenas de gente, como un retorno (con excepción de los cubrebocas y el omnipresente gel antibacterial) a un tiempo anterior y más benigno, a como eran las cosas antes de que la pandemia viniera a sacudirnos con un golpe de realidad inapelable.

Caminaba sin rumbo, que es una de las formas más placenteras de pasear, y de pronto me encontré en Poland Street. Me dio gusto, como siempre: ahí vivió William Blake con su esposa Catherine en los primeros años de su matrimonio, y ahí fue que el espíritu de su adorado hermano Robert, ya fallecido, le reveló el método de impresión que utilizaría desde entonces en sus libros iluminados. Ya no existe ese edificio; en su lugar hay un enorme bloque de oficinas en renta, como una caja de cartón. Enfrente hay un pub, The Kings Arms, donde en 1781 fue revivida la Antigua Orden de los Druidas, y donde al parecer se siguen reuniendo, para bien o para mal.

Al llegar a una esquina me llamó la atención una placa azul de English Heritage, según la cual en ese lugar había vivido Percy Bysshe Shelley. ¡Doble alegría!

No recuerdo haber visto esa placa antes, pero de regreso a mi casa me apresuré a investigar, y en efecto, en 1811 Shelley y su amigo Thomas Hogg se hospedaron en el número 15 de Poland Street (el edificio sigue en pie), tras haber sido expulsados de Oxford por haber publicado La necesidad del ateísmo. Aunque Shelley, enamorado del papel tapiz en sus habitaciones, parece haber exclamado: “Tenemos que quedarnos aquí, ¡para siempre!”, su estancia ahí fue de lo más breve.

Recientemente impartí una charla en línea para la Casa Universitaria del Libro de la UNAM sobre el Frankenstein de Mary Shelley y sus orígenes en la famosa (y por demás intensa) reunión en la Villa Diodati, junto al lago Lemán en Suiza. Cuando di ese paseo por Soho estaba todavía inmersa en el mundo atormentado, incendiario y fértil de los Shelley, Byron y Polidori, así que me dio un gusto enorme encontrarme con ese rastro del paso del poeta como el saludo de un mundo anterior con mucho a mi mundo pre-pandemia, y saber que había compartido una calle con Blake. ¿Qué importaba que hubiera sido en épocas distintas? Estos encuentros (por cuya promesa me vine a vivir a Londres, y me quedé, hace ya casi 23 años, cosa que quizá sea un signo de locura), no están constreñidos por el tiempo. Blake y Shelley: un encuentro; ahora me reunía yo con ellos, y nadie podría afirmar con evidencia que no es cierto.

¿Pero qué tanta verdad hay en esta visión romántica del tiempo? Esa misma mañana había estado pensando, atribulada y por enésima vez, en la forma cada vez más automatizada en que conducimos nuestras vidas. El tiempo perdido, irrecuperable para siempre jamás, en nuestras computadoras y teléfonos; la vida succionada por el hoyo negro de internet; los cajeros de autoservicio en tantos supermercados con máquinas que hablan en fatigosa cacofonía; la incontinente proliferación de contraseñas y códigos de verificación, y la infinidad de formas de almacenar datos, controlar nuestra identidad, acelerar el progreso y sus engendros e “interactuar” con máquinas de las que sé poco o nada, porque si supiera más, no sé si la vida en este mundo me seguiría pareciendo tolerable.

Esa tarde, sin embargo, fue de todas formas con alegría que me senté en un café muy simpático que acababa de descubrir. Planeaba instalarme ahí como una hora para ponerme a escribir. Escribir en los cafés es uno de los placeres más excelsos de mi vida desde hace casi cuarenta años, y uno que, tras los embates del Covid, he empezado a recobrar hace apenas relativamente poco, así que la tarde prometía ser fructífera. Fue mi mala fortuna, justo cuando empezaba a levantar el vuelo, oír que me había llegado un mensaje en el celular (y aclaro que mi celular no es siquiera “inteligente”, pues estoy convencida de que la inteligencia del celular es directamente proporcional a la que le es restada a su dueño, quiera que no). Ignoré el mensaje. No pasó un minuto sin que me llegara otro, y otro más, y entonces miré: eran de mi banco. Decían que habían detectado una transacción sospechosa en el café tal y tal, de dos libras con cuarenta peniques; que respondiera de inmediato si había sido yo la infractora, o bloquearían mi tarjeta.

Esa es otra de las secuelas de la pandemia: el miedo a tocar dinero, y los cada vez más establecimientos que de hecho sólo aceptan pago con tarjeta. No sabía si responder al mensaje. ¿Qué tal que fuera un intento de estafa, y si respondía “sí”, de alguna manera incomprensible tendrían los verdaderos maleantes acceso a mi cuenta y me la vaciarían? Luego recibí una llamada: un mensaje automatizado también, insistiendo: ¿había comprado yo ese maldito café, sí o no? Ya enfurecida a estas alturas, llamé a mi banco. Me dijeron que sí, que los mensajes y llamadas eran suyos. Les pregunté cómo diablos comprar un café, gastar dos míseras libras con cuarenta en la ciudad en donde vivo, puede ser considerado una transacción sospechosa. Me dijeron que las transacciones así calificadas son elegidas de manera aleatoria, por máquinas, está de más decirlo, “para seguridad de nuestros clientes”, y que hay que responder de inmediato.

En esto se me fue media hora. Durante los siguientes treinta minutos intenté trabajar, sobra decir que sin mucho éxito, y ya se me había enfriado el café. Todo se había alterado; mi alegría había quedado fragmentada sin remedio de esa forma espantosa que sólo logra infligir una tecnología que ni entendemos ni controlamos. Como en un barco triste que zarpa sin hacer ruido, Blake y Shelley se iban alejando, con su fuego y con sus versos.

“Se va a caer”, pensé. Un día todo esto se va a caer, no importa cuán grande el diabólico ingenio, cuántos satélites y basura hayamos dejado flotando en el espacio, y no importa cuánto dependamos de la ininteligible maraña. Se va a acabar, simplemente porque ese es el destino de todas las cosas, y esa es una forma de esperanza, aunque sepa muy bien que no me tocará verlo, ni recobraré jamás la vida (ahora lo veo) feliz e inocente que tan bien recuerdo anterior a la conquista de internet y su caterva de siniestros hermanos. Cada que alguien me dice que no, que el imperio de la tecnología no acabará nunca, yo respondo que eso se decía del imperio romano, y miren ahora. La hecatombe comenzará probablemente por esos bucles que ya forman parte de nuestra vida cotidiana, en que los aparatos avanzadísimos que usamos empiezan a hacer cosas que ya ni los técnicos entienden y nos dejan sumidos en estados tan pueriles como espantosos de impotencia, ansiedad y furia. Uno de esos bucles, pero enorme. Cuando empiece a caer la silenciosa tiranía, nuestra pobre civilización va a hundirse en un caos indescriptible. Y bien merecido lo tendremos.

O no, porque ¿cuántos de nosotros decidimos que queríamos vivir así? A la gran mayoría nos ha sido impuesto. ¿Cómo? ¿Por quién? Por esa masa amorfa, “la sociedad”; por la aceptación sin líder identificable de que así son las cosas, ahora. Por un incomprensible error de juicio colectivo según el cual todas estas novedades son necesarias para nuestro funcionamiento y existencia. Por hombres y mujeres de negocios y desequilibrados genios de la informática que se divorciaron de la realidad muchísimo antes que el resto de nosotros.

Una de las reflexiones a que me llevó la preparación de la charla sobre Frankenstein o el moderno Prometeo (1818), fue que suscitar hoy día un impacto semejante al de la novela de Mary Shelley es del todo imposible. Lo que ha visto la humanidad desde entonces nos ha curado, literalmente, de espanto. Así como nadie se asombra ya de vivir subyugado por los actuales y sin duda oscuros Molinos Satánicos de Blake, la arrogancia de legiones de Víctor Frankensteins tentando los límites de la incumbencia humana ya no nos hace siquiera pestañear. No queda ya quién se escandalice por la invención de una o centenas de criaturas monstruosas. Más bien sucede lo contrario: los deslumbrantes avances de nuestra civilización son aplaudidos en la prensa y en la laberíntica cámara de ecos de la red, y recibidos con insaciable entusiasmo; las mutilaciones, injertos, cópulas y aberraciones que se realizan día con día bajo la luz neutra de infinitos laboratorios en todo el mundo son indiscriminadamente recibidos con loas por su servicio a la humanidad, con el mismo discernimiento con que hacemos largas filas de cuándo en cuándo para adquirir el último invento de Apple: esos son nuestros rituales sucedáneos.

Todos somos partícipes, y aunque los cuestionamientos éticos sobre estos avances supuestos y reales merecen cada uno un espacio de debate serio, éste se pierde sin remedio en el exceso (des)informativo. Lo que queda es nada más nuestra mansa aceptación. Conectados a un artilugio al que le vamos colgando más y más “apps” hasta que nuestra vida entera depende de él, ahora todos somos la criatura imaginada por Mary Shelley, monstruosa y a la vez víctima desamparada. Y en cierta medida, cada que añadimos una “app”, hacemos clic aquí o allá sin preguntarnos por qué, cada que integramos dichos artificios en nuestra vida individual y social, todos somos también Víctor Frankenstein.

Si nos detenemos un momento y tratamos de pensar con el detenimiento que cada vez le es más arduo a nuestra atención fragmentada, vemos claramente que la manera en que vivimos los habitantes del siglo XXI no es normal; de que no hay cordura ni sensatez alguna en trocar la realidad por una realidad virtual, y aceptar pasivamente que todas las acciones de nuestra vida dependan de esos artilugios, aplicaciones y pantallas que generan cantidades ingentes de basura, que no entendemos, en definitiva no controlamos, que nos han arrebatado nuestra privacidad y nos están arrebatando, también, la vida. O al menos una vida humana que merezca ese nombre.

Tan lejos estamos de la lucidez de Mary Shelley, que rara vez nos provoca escalofríos ser testigos de cómo nuestros semejantes visitan lugares hermosísimos en todo el planeta, o museos y galerías que exhiben obras de arte excelsas, sin ver jamás directamente ni paisaje, arquitectura, monumento o arte: armados de sus celulares, llegan con andar desatento, toman la foto o el video y se van, sin dedicar ni un instante de contemplación ni contacto directo a su experiencia. Zombis, autómatas, con imágenes y videos alimentamos las redes sociales, atosigamos con ellos a quienquiera que nos acompañe en un café, para que también la interacción con otros sea mediatizada y nos aparte de los placeres y riesgos de la verdadera conversación, y nos vamos llenando la cabeza de ruido. Paja informática. La concreta sordidez del algoritmo. Despojados por mano propia de la soledad contemplativa y fecunda, quedamos varados en esa otra soledad: la que mata, la de la pura y llana desolación. ¿Hemos de sorprendernos de los altos índices de depresión entre nosotros?

Que el monstruo ya no nos espante de manera colectiva, sin duda me espanta a mí. Sí, me deprime. Me recuerda hasta qué grado soy extranjera de mis tiempos. No soy, lo sé, la única que, aletargada y todo, sin saber cómo escapar, tiene plena conciencia de la perversidad intrínseca en nuestro retorcido amorío con la tecnología. Afortunadamente, todavía es posible, por ejemplo, caminar con nuestros propios pies por Poland Street, y encontrarnos merced a un arrebato de la imaginación con William Blake y con Percy Bysshe Shelley, abolir el tiempo por un instante y luego sentarnos en un café con ganas de escribir, actos todos estos indudablemente humanos en los que generaciones pasadas pueden reconocerse. Lo agradezco. Me pregunto también de qué recursos tendré que echar mano para conservar la suficiente entereza de espíritu que impida que los mensajes de texto de un robot en mi teléfono rompan ese vínculo cardinal con la humanidad que nos precede, y con la que vendrá.

En la frontera entre el año pasado y el que apenas comienza, estoy pensando en el futuro. En el que estamos creando ahora mismo, inmunes al horror, y que con imperdonable desparpajo estamos dejando como herencia (junto al desastre climático) a los jóvenes, los niños y los que están por nacen. Estoy preguntándome por qué nos cuesta tanto encontrar los arrestos para decir: “No. No consiento a ser despojada de mi humanidad”.

*Image by Luc Mercelis

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

Adriana Díaz-Enciso es poeta, narradora y traductora. Ha publicado las novelas La sed, Puente del cielo, Odio y Ciudad doliente de Dios, inspirada en los Poemas proféticos de William Blake; los libros de relatos Cuentos de fantasmas y otras mentiras y Con tu corazón y otros cuentos, y seis libros de poesía. Su más reciente publicación, Flint (una elegía y diario de sueños, escrita en inglés) puede encontrarse aquí.

©Literal Publishing. Queda prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta publicación. Toda forma de utilización no autorizada será perseguida con lo establecido en la ley federal del derecho de autor.

Las opiniones expresadas por nuestros colaboradores y columnistas son responsabilidad de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente los puntos de vista de esta revista ni de sus editores, aunque sí refrendamos y respaldamos su derecho a expresarlas en toda su pluralidad. / Our contributors and columnists are solely responsible for the opinions expressed here, which do not necessarily reflect the point of view of this magazine or its editors. However, we do reaffirm and support their right to voice said opinions with full plurality.