Raimund Girke: The German Informel. The Union of Opposing Tendencies

Benjamin Lima

Images courtesy of the Gallery Sonja Roesch

Light in Rest and Motion:Raimund Girke’s painterly investigations

The oeuvre of the German painter Raimund Girke (1930-2002) is a case of study in how the union of opposing tendencies can lead to sustained productivity over a long-term career. For example, Girke investigated numerous different painterly conceptions, but even while doing so, he continued to remain within the same basic paradigm ofcontrolled geometric abstraction. He first developed this approach inthe context of the 1950s school known as art informel, which was a European counterpart to American Abstract Expressionism. For the remainder of his distinguished career, he continued to work out the possibilities of informel-type painting, withstanding any pressure to follow such high-profile trends as pop art, conceptualism, or neoexpressionism. However, while remaining within the same basic paradigm, Girke continued to experiment with his approach, developing arange of ideas during the different periods of his career. For another contrast, although the building blocks of pure geometric abstraction are often equated with non-visible, spiritual or conceptual phenomena, in Girke’s case, they are converted into something quite objective,that is, an exploration of fundamental physical phenomena such aslight, motion, rhythm, and vibration. The gesturality of a typical abstract painter (i.e. a Pollock or De Kooning), in Girke’s work is slowed down, cooled off, or thickened in order to take on a more substantial or objective character.

In spite of the fact that Girke’s work does not frequently include typically autobiographical or narrative elements, we might still wonder whether his life experiences of uprooting and migration contributed to its motivations. Girke moved several times in his life, from his birth in Heinzendorf, Lower Silesia, to the Weserberg area with his family, and then to Hanover and Düsseldorf for his education. The exile from East to West Germany is an experience the artist shared with numerous other leading painters in this period, such as Sigmar Polke (also born in Silesia), Gerhard Richter, and Georg Baselitz. Silesia, the place of Girke’s birth, however, found itself not merely behind the Iron Curtain, but outside of Germany altogether. After the war, the Allies transferred the territory east of the Oder River to Poland, at which point the German population was removed to the Western territories and lands such as Silesia became no longer German. Although the title of a 1956 Girke painting, Memory of a Landscape, suggests the significance of this experience, the work itself conceals details of the landscape behind an interlocking network of brushstrokes.

In spite of the fact that Girke’s work does not frequently include typically autobiographical or narrative elements, we might still wonder whether his life experiences of uprooting and migration contributed to its motivations. Girke moved several times in his life, from his birth in Heinzendorf, Lower Silesia, to the Weserberg area with his family, and then to Hanover and Düsseldorf for his education. The exile from East to West Germany is an experience the artist shared with numerous other leading painters in this period, such as Sigmar Polke (also born in Silesia), Gerhard Richter, and Georg Baselitz. Silesia, the place of Girke’s birth, however, found itself not merely behind the Iron Curtain, but outside of Germany altogether. After the war, the Allies transferred the territory east of the Oder River to Poland, at which point the German population was removed to the Western territories and lands such as Silesia became no longer German. Although the title of a 1956 Girke painting, Memory of a Landscape, suggests the significance of this experience, the work itself conceals details of the landscape behind an interlocking network of brushstrokes.

We can gain a clearer sense of Girke’s work by successively considering two of the distinct stages in his work: his early mature works of the 1950s, and his late works of the 1990s. The former is among Girke’s best-known periods of work; examples of his painting from the 1950s were chosen to be included in two prestigious exhibitions that, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, attempted to survey German art during the period of its Cold War division. Another 1959 work is in the permanent collection of the Busch-Reisinger Museum at Harvard University, perhaps the most prominent American collection to hold the artist’s work.

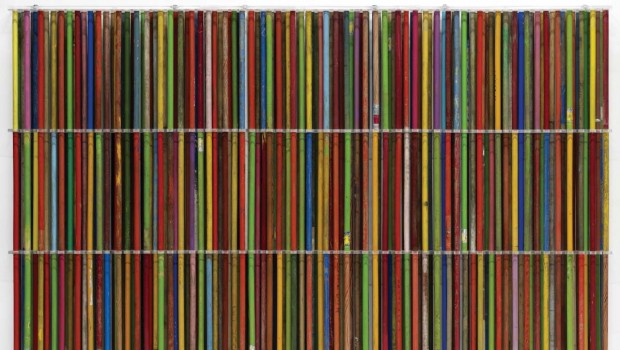

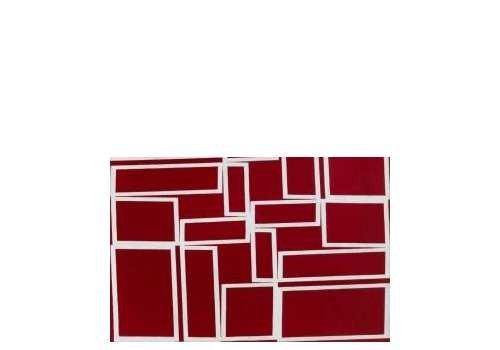

I n these years, Girke often explored questions of the subjective and the objective using the devices of the grid and of repetition. Two such works, both included in the 1997 Berlin exhibition Deutschlandbilder, are Disturbed Order (1957) and Large Vibrations (1958). In Disturbed Order, rows of organically irregular blocks proceed horizontally, closely packed together like rows of teeth. Within each block, areas of light and dark gray meet each other in varying configurations, implying different degrees of three-dimensionality, and sometimes spilling over the boundaries of the grid. Large Vibrations is closely related to another painting, Ohne Titel (1959), which was included in the 2009 Nuremberg survey Art of Two Germanys: Cold War Cultures. In both of these, gently curved gray-white vertical strokes are aligned in a series of rows that move horizontally across the surface. Three darker horizontal lines, partly hidden and partly revealed by the verticals, divide the surface into textile-like bands.

n these years, Girke often explored questions of the subjective and the objective using the devices of the grid and of repetition. Two such works, both included in the 1997 Berlin exhibition Deutschlandbilder, are Disturbed Order (1957) and Large Vibrations (1958). In Disturbed Order, rows of organically irregular blocks proceed horizontally, closely packed together like rows of teeth. Within each block, areas of light and dark gray meet each other in varying configurations, implying different degrees of three-dimensionality, and sometimes spilling over the boundaries of the grid. Large Vibrations is closely related to another painting, Ohne Titel (1959), which was included in the 2009 Nuremberg survey Art of Two Germanys: Cold War Cultures. In both of these, gently curved gray-white vertical strokes are aligned in a series of rows that move horizontally across the surface. Three darker horizontal lines, partly hidden and partly revealed by the verticals, divide the surface into textile-like bands.

These paintings can be recognized as examples of an approach to art informel that developed most distinctively in the West German art center of Düsseldorf, which was at a point of high influence in the 1950s. Of course, the Düsseldorf Art Academy had been well established for many generations, when Girke studied there, as it still is today. But during the time after World War II, the years of reconstruction and the economic miracle, the city also had a unique significance in reintroducing West Germans to currents of modern art that had been suppressed during the Nazi years. There were gallerists such as Alfred Schmela and Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, who gave many French and American artists their first showings in Germany, as well as the painters K. O. Götz and Gerhard Hoehme, who introduced countless students to ideas of abstraction and the avant-garde. Whereas works by artists such as Hoehme and Emil Schumacher, members of the artists’ group known as Gruppe 53, exemplify the tendency of West German informel to express a sense of individual, existential drama, by contrast Girke’s work of this period seems more detached and analytical; indeed, more objective. It seems as if the traumas that troubled earlier informel work have been left behind.

By comparison, if we examine Girke’s work from the last part of his career in the 1990s, we see a mode of painting that displays both a sense of power, as the compositions are dominated by a few, substantial forms, and a sense of immateriality, as these forms appear to dissolve and become translucent. In these commanding works, such as The Force of the Vertical or Extremes Blau, both from 1997, lighter areas resolve into ghostly vertical columns that twist as if subjected to extreme torqueing forces. The exhibition last fall at Gallery Sonja Roesch notably included several of these, such as Schneller Wechsel (1994) and Spontan (1998) as well as Extremes Blau. Although these works continue the investigation of essentially physical phenomena—light and vibration—they are also open to symbolic or metaphorical meanings, in particular, those associated with the color white. For that matter, the vertical columns could also be read as figures of some kind, whether human or otherwise. If the later work displays a sense of openness and freedom, more so than the earlier period, nonetheless they share the discipline and rigor that is common to all of Girke’s painting. This consistency is what distinguishes Girke’s work, and makes it possible to return once and again to it. The same spirit of discovery and investigation that the artist brought to his work is available to its viewers as well.

Posted: June 30, 2012 at 4:27 pm