Shadow

Sombra

Jazmina Barrera Velázquez

English translation by Dave Oliphant

Soy como el hombre que vendió su sombra, o mejor, como la sombra del hombre que la vendió.

Fernando Pessoa

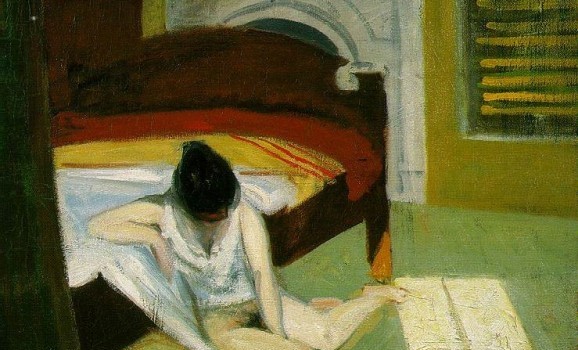

Every day we attest to that obscure, silent, and faithful double that ac- companies us. And that links us to the universe. Even at noon, the hour without shadows, we darken the planet a little bit, perfectly aligned with the sun and earth. Because we are stuck to our shadow, since al- ways some tip of us touches it. For that reason Peter Pan must sew his shadow to his figure, so as not to lose it, which is curious if we consider that flying is the only instance–aside from our brief leaps–in which we would see ourselves physically separated from our shadows, and as Peter Pan knows, would even teach us how to fly.

This “other” that resembles us, but is faceless, that is like us, but has the capacity to widen, to become thin, or to grow depending on the light (the novel, Top of the World, translated in the Spanish version as The Country of the Long Shadows, owes its title to the northern terrains, the lands of the Eskimos, where for months the sun hardly shows itself to the earth and people cast very long shadows, extending themselves toward infinity), is the perfect metaphor for a Manichean culture that finds a “good” and an “evil” in almost every- thing, a side of light and another of shadow, or even more recently, one conscious side and another, unconscious. Just as the earth has a moment of day and another of night, we humans always have, except for just at midday, our side of daylight and our shadow of night:

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

T. S. Eliot says, referring to our shadow, that in the morning it follows us like a little lap dog and in the afternoon, threatens to outrun us.

Let us consider now the shadows at night. What happens to this side of us in the blackness? Does it dissolve in its element? In Salman Rushdie’s novel, Haroum and the Sea of Stories, there exists a country so dark that the shadows can move around on their own, since the shadows in the darkness do not have to take the same form all the time. So the shadows in Rushdie’s story have their own personalities and can even fight with their owners, yet never be separated from them. Only the villain of the story has committed this atrocity and, little by little, has become more somber until he’s the same as his shadow, which now moves freely about as his double.

The word awe [asombro in Spanish] is one of many that derives from shadow [sombra in Spanish], as do penumbra, sombrero, som- brilla [half-shadow, hat, and sunshade], y sombrío [somber, shady, shaded]. A-sombrarse in Spanish means, in its original definition, to be frightened by the appearance of a shadow. In section XI of Wallace Stevens’ poem, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” a man confuses the shadow of his carriage with blackbirds:

He rode over Connecticut

In a glass coach.

Once, a fear pierced him,

In that he mistook

The shadow of his equipage

For blackbirds.1

The shadow personifies an immaterial presence. For example, the spirit (in certain groups, it is believed that when someone dies he can leave his shadow, that is, his spirit, in the place where he died). It is the shadow that causes a feeling of fright, like a presentiment, like an augury. Immediately, however, we question ourselves as to the ac- tual meaning of the word awe [asombro], which describes the sudden sensation of the strange or the surprising, that does not necessarily come from anything harmful. Fright is an ambiguous feeling that de- rives from the mysterious, the wondrous or the odd, whether positive or negative, something similar to the sublime. For that reason, Jung recognizes the possibility that the shadow is converted into “the heal- ing serpent of the mysteries.” Surely it is because of this that fantastic stories have made the shadow into a character that while mysterious and eccentric, is not necessarily evil. The best stories are shaped be- neath the shadows.

1 In English “shadow” comes from Old English sceadwian: “to be protected as a bird that covers itself with its wings.

Soy como el hombre que vendió su sombra, o mejor, como la sombra del hombre que la vendió.

Fernando Pessoa

Todos los días comprobamos a ese doble oscuro, silencioso y fiel que nos acompaña. Y que nos une con el cosmos. Incluso a las 12 p.m., la hora sin sombras, eclipsamos un poquitito al planeta, perfectamente alineados con el sol y con la tierra. Porque estamos pegados a nuestra sombra, siempre algún extremo nuestro la toca. Por eso Peter Pan debe coser su sombra a su figura para no perderla, curioso si consideramos que volar es la única instancia –además de los breves saltos– en la que nos veríamos físicamente separados de nuestra sombra y Peter Pan sabe, incluso enseña a volar.

Este “otro” que se nos parece, pero no tiene rostro, es como nosotros, pero tiene la capacidad de ensancharse, de enflacar o de crecer según la luz (la novela llamada El país de las sombras largas debe su nombre a los terrenos nórdicos, tierras de los esquimales, en donde durante meses el sol apenas se asoma a la tierra y las sombras de las gentes se proyectan larguísimas, como extendiéndose hacia el infinito), es la metáfora perfecta para una cultura maniqueísta que encuentra en casi todo un “bien” y un “mal”, un lado de luz y otro de sombra, o incluso más recientemente un lado consciente y otro inconsciente. Igual que la tierra tiene un momento de día y otro de noche, los humanos tenemos siempre, salvo exactamente al mediodía, nuestro lado de día y nuestra sombra de noche:

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

[y te enseñaré algo diferente, tanto

de tu sombra por la mañana caminando detrás de ti

como de tu sombra por la tarde subiendo a tu encuentro;

te enseñaré el miedo en un puñado de polvo.]

Dice T. S. Eliot, refiriéndose a nuestra sombra que en la mañana nos sigue como un perrito faldero y por la tarde amenaza con sobrepasarnos.

Consideremos ahora las sombras de noche. ¿Qué pasa en la negrura con este lado nuestro? ¿Se disuelve en su elemento? En la novela de Salman Rushdie Haroum and the Sea of Stories existe un país tan oscuro que las sombras pueden moverse allí a su voluntad, porque las sombras en la oscuridad no tienen que adoptar la misma forma todo el tiempo. Así que las sombras en la historia de Rushdie tienen su propia personalidad y pueden hasta pelearse con sus dueños, aunque no separarse. Sólo el villano de la historia ha logrado esta atrocidad y se ha vuelto poco a poco más sombrío hasta igualarse con su sombra, la cual ahora se mueve libremente como su doble.

La palabra asombro es una de las muchísimas que provienen de sombra, como penumbra, sombrero, sombrilla y sombrío. A-sombrarse quiere decir, en su sentido original, asustarse por la aparición de una sombra. En el fragmento xi del poema de Wallace Stevens, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”, un hombre confunde la sombra de su equipaje con mirlos:

He rode over Connecticut

In a glass coach.

Once, a fear pierced him,

In that he mistook

The shadow of his equipage

For blackbirds.1

[En una calesa de cristal

Recorrió Connecticut.

Una vez, lo traspasó un temor

Cuando confundió

Con los mirlos

La sombra de su equipaje.]2

La sombra personifica una presencia inmaterial. El espíritu, por ejemplo (en ciertas comunidades se cree que cuando alguien muere puede dejar su sombra, es decir su espíritu, en el lugar donde murió). La sombra entonces causa el sentimiento de asombro como un presentimiento, como un augurio. Inmediatamente, sin embargo, nos preguntamos por el sentido actual de la palabra asombro, el que describe la súbita sensación de lo extraño o lo sorpresivo, que no deriva necesariamente de algo dañino. El asombro es un sentimiento ambiguo que surge de lo misterioso, lo maravilloso o lo raro, ya sea positivo o negativo, algo parecido a lo sublime. Es por eso que Jung reconoce la posibiliad de que la sombra se convierta en “the healing serpent of the mysteries”. Por eso seguramente las historias maravillosas han hecho de la sombra un personaje que no por misterioso y peculiar es necesariamente maligno. Las mejores historias se forjan bajo la sombra.

1 En ingés “shadow” deriva del inglés antiguo sceadwian: “protegerse como un ave que se cubre con sus alas”.

2 Traducción de los Materiales de lectura de la unam.