THE AFTERLIFE OF COTTON: YUMA

Cristina Rivera Garza

In The Woman in the Dunes, the novel that Japanese author Kobo Abe published in 1962, a young botanist in search of a rare beetle is trapped at the bottom of a sand pit. He had been invited to spend the night at the home of a widow, only to find himself unable to get back up to the surface the following morning. Perhaps he should have guessed something was wrong when he had to use a rope to descend to the dwelling and when he realized that the woman—petite and otherwise fragile—used the night hours to fill buckets with sand to no end. There was supposed to be a lesson in all this—or at least some matter for profound thinking. The very survival of the village, after all, depended on the Sisyphean-like task of an outcast woman. Lacking any understanding of freedom, the woman completed her routine with a resignation that was barely human. The sand never ceased to threaten the pit.

Sand also appears to be merciless in the dunes that surround Yuma. I recall Abe’s novel when the sun is at its highest and the border—that wall that emerges out of nowhere to divide a continuous landscape—resembles a mirage. Perhaps all the immigrants who have walked through Aridoamerica and crossed this imaginary, this relentless, this lethal line have, in fact, fallen into a sand pit. Perhaps this is a trap. Our trap. Are we still filling buckets of sand to keep the village alive?

We visited Arizona earlier that summer, the summer we went east. After living in the United States for 26 years, I thought it was time to see the Grand Canyon. It took me all these years to figure out that colorado—the word most commonly used in Spanish to qualify this miracle of rock and time—was not a reference to the color or to the state, but to the river. The Cañón del Colorado lies in Arizona, of course. Flowing unabated for millions of years—some are betting on seventeen as the exact number—the Colorado River has carved out its own place in our history. Erosion is but a form of persistence, a meandering plot line.

This is the image: men and women forming a line and smiling. Men and women wearing jeans and loose t-shirts and those ragged baseball caps with added back flaps standing there, all of them, by the back door of the store, waiting. Their mouths, open. I can see their gums and teeth as they burst into laughter. Men and women speaking Spanish, calling each other comadre or compadre, happy. Seemingly joyous. I did not ask how much they got for a day’s work, but some of them went immediately into the store and bought cans of iced coke or, better, iced beer, duly wrapping them in paper bags before jumping into the driver’s seat of battered trucks. The sound of worn-out engines, starting again and again. The sound of tires against loose gravel. The odd thing about vanishing is that it occurs in the blink of an eye.

Erosion is a form of persistence, a plot line that carves out a place of its own in time and landscape.

We had not yet crossed the Arizona state line when we decided to stop at the largest gas station off the main road. It was a little after 2o’clock. Gas prices had dropped dramatically as we moved east and, even when the car strictly speaking did not need it yet, we wanted to take advantage of the unexpected bargain. We needed ice, too. And water. We needed to stop. Driving for hours in a car without air-conditioning through the desert—that’s what we were doing the summer we went east. Was this a mild form of mental derangement, a case of reckless behavior, a dumb choice? Perhaps all of the above. Most likely.

“Did you see them?” I asked, as I came back to the car carrying a bag of ice.

They turned their heads and looked at me and I knew, suddenly I knew. A modern version of Abe’s woman of the dunes, indeed. Poor Cristina, filling buckets with sandwords. To no end. To no avail.

“The men, the women,” I said hesitantly. “The line of men and women by the bathrooms. There,” I finally pointed them out.

Years earlier, in a novel I have always failed to finish, I had placed artist Max Ernst at the doors of an old Mental Health Asylum in Campo Alaska, a military garrison first built in the 1920s by then governor Abelardo L. Rodríguez to conduct state affairs away from the unbearable summer heat of Mexicali, the capital city of the northern territory of Baja California. The military barracks came to be a makeshift hospital for mentally ill men and women over time. The sound of the wind through the pine trees gave its unique name to this mountain range: La rumorosa, the Whispering Woman. Erosion, which is a form of persistence, gave it shape. Color. Substance. Marx Ernst had come to the United States in 1942, returning to Europe some eleven years later, in 1953. I was aimlessly walking through the insane asylum-turned-museum site when I found some pieces of rusted wire on the dry fields. Their intricate forms and, especially, their hue, reminded me of Ernst’s work. I had no idea back then that Ernst had in fact lived in Sedona, and that some of his most important work—the kind of work that had impacted me as a young woman—took from Arizona its relentless nature, its rugged texture and maligned silhouette. “In my sanctuary, I keep with me the head and arms that touched thunder,” wrote Ernst at the base of the Hundred Headless Woman, a collage.

Vanishing is the name of a game that is geopolitical in nature.

Vanishing takes time. One day, a young woman leaves her home in Central America to traverse a ferocious country and then this line, this relentless, this imaginary, this all-too-real line, and is never heard from again. Vanishing is easy. One day, a man shows his visa at the gate and enters the pit, never to return. One day, after years of filling buckets with sand, a woman recalls the smell of soap from back home and pauses for a moment, and sighs, only to continue her task, unabashed. One day, a man plants a tree in his front yard and wonders if this land will one day claim him, greeting his bones, his fingernails, the tips of his thinning hair. Vanishing is a form of erosion. A form of persistence. A carving out.

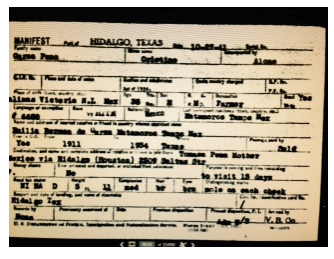

The summer we went east, from sea to shining sea in an old car without air-conditioning, I had begun my naturalization process. I had just learned that my grandfather, a man after whom I was named, had lived in the United States from 1911 to 1934, crossing the border back and forth many times afterwards. I found the immigration records that proved this to be true at the National Archives in D.C. even later that summer. He had first crossed the border at the age of three, learning English and working as a farmhand or a sharecropper in the cotton fields of southern Texas as time evolved. Because time flies; and vanishing takes time. Cotton also took him back to Mexico—the promise of cotton, the living and dying of cotton—a married man already, with tons of experience in the fields and cities of Texas, and records that proved his participation in societies of mutual aid and other urban and rural organizations. In my sanctuary, I too keep the arms and heads that touched thunder, Max.

When we reached the checkpoint, an Arizona officer asked for our papers, his eyes hidden behind aviator shades. I shuddered. It was just for a second, perhaps even less, but I shuddered, as I am always prone to do before immigration officers. Guests do that at times when facing the contours of their lodgings.

“Did you see the men and women standing in line behind the store at the gas station?” I asked again, as soon as we found ourselves driving on the Arizonan portion of Highway 8. The wind of the desert blowing against our teeth and gums as we burst into laughter.

I have yet to see my first cotton plant.

Cristina Rivera Garza is a Mexican author and professor best known for her fictional work, with various novels such as Nadie me verá llorar winning a number of Mexico’s highest literary awards as well as awards abroad. She is a regular contributor of Literal Magazine via her column Overcast.

Cristina Rivera Garza is a Mexican author and professor best known for her fictional work, with various novels such as Nadie me verá llorar winning a number of Mexico’s highest literary awards as well as awards abroad. She is a regular contributor of Literal Magazine via her column Overcast.

Posted: November 10, 2015 at 10:51 pm