The Natural Route (Fragments)

La ruta natural (fragmentos)

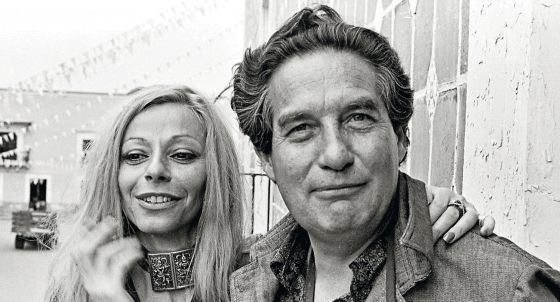

Ernesto Hernández Busto

Translated by Tanya Huntington

Just as Leopardi associates poetics with vagueness, imprecision, or the effect of the real passed through the sieve of memory, Valéry warns us in a famous quote that the syntax and words of a poem must be “as precise as possible, but the meaning must remain imprecise, multiple, never fully identifiable with the limited function of terms.” The poem becomes a precise assemblage that gives rise to imprecision; therein the radical strangeness of poetry, of the state of invention it bestows upon us.

* * *

Summer in Grossetto, where I have come in search of the poet and psychiatrist Pedro Marqués de Armas. A “Refuge City” for writers in the Tuscan Maremma: boring as hell. A harsh landscape of dry yellow. And as if that weren’t enough, the worst heat wave in history. There is no escape. By day, it is all we can manage to read in bed, mouths agape, a reptilian routine. By night, we converse on the terrace.

One torrid evening, Pedro tells me the story of how he met the poet Ángel Escobar. I don’t take notes, but it all continues to rattle around in my head. A few days later, I write down this version of his story in a fairly liberal first person:

“I first came to the Hospital as an intern years ago, with the gratuitous presumption of any recently graduated psychiatrist: one more among the ranks of the incurable mechanicists of the soul. Valdés Mier made me his protégé, and I felt as if I were Charcot’s favorite pupil, the kind who sees hysteria springing up on all sides –that woman who entered my office one afternoon, so impressive with milk still flowing from her breasts, an ill-treated organic catatonia.

Although the worst of doctrinary classification and reflexological therapy had come and gone, out there on the island we psychiatrists had to deal with all sorts of ruses; the strange pretenses or fabrications of certain patients whose profiles were nowhere to be found in the manuals. Symptoms that had always seemed to me to be subtle forms of psychic response to political demise or the fiasco of free will; symptoms that had found other channels for their unending twists and turns. Some of them were laughable, others, more dramatic –for example, the ongoing chain of suicides I had to deal with from the start of my internship, many of them due to malpractice. I don’t know how I managed to bear it all, but there I was, attending almost indifferently to a battalion of pathological liars, misfits, and suicidal patients until I came to the Poet, a moving case of actual schizophrenia, the interplay of voices that tormented a powerful mind. By the time he was admitted to the hospital, the Poet was already a clochard but nonetheless, he helped me find a way out of that world of cold, clinical reports and insular tragedies. He would enter my office with his puppeteer’s gait, sit on a chair and recite his schizoid odes nonstop. And then he would leave, that same gait denoting a person of considerable importance. Valdés Mier would laugh at me, at my interest in the delirium of a man who was Rimbaud one day and Antonio Maceo the next, while at the same time insisting to me that he should be locked up as soon as possible. But since I was indebted to the Poet and his friends, I paid him back by receiving him by day in the hospital every week and prescribing placebos that he would carefully store in the small cardboard box that always bulged inside his shirt pocket.

Until one day, I could do no more and they finally admitted him. And he escaped in order to stick his head underneath a car, in the least graceful way imaginable. ‘He must be someone important,’ said the woman who found him in the middle of the street when she came to alert us at the Hospital. But it was late, too late, like everything else in that country.”

* * *

One of those interminable tropical rains. Down on the street, people struggle with their frayed umbrellas, a regiment of mocking corollas under a gray taffeta sky. Gazing through the window, I reflect on my birdless childhood, when a starling was as rare as those jewels the size of pigeon eggs that rest behind bulletproof glass in some museums, or mounted on the scepter of a former kingdom, now a republic. Therein my excursions, now as an adult and with the invincible alibi of paternity, to every possible zoo in order to flesh out these childhood fantasies. My discovery of a pheasant in a Polish village. Or the ruff of a duck, reminiscent of a rare emerald.

* * *

It isn’t hard to discover how certain traits, a latticework of physical features that comprise the classic image of beauty, immediately inspire confidence or even invite us to come closer. This mostly happens with people who are dazzlingly, persuasively attractive. But such proximity seems merely an illusion to one of the two parties, given that more often than not, beauty of this kind is imperceptible to the one who lives, in a manner of speaking, inside it. Afterwards, inevitably, the reticence, the mistrust typical of someone who is different, who even when trying to be friendly cannot help but make us feel as if we were being treated with a measure of indulgence.

The voyeur’s impulse to approach the object of his contemplation is left truncated, like a missed handshake, and he will therefore seize any pretext for dissimulation; after daring there always comes a leveling out, a way of compensating for having debased oneself. Physical beauty, in this sense, always seems unjust because it is unequal, alien to the unchosen ones who, out of devotion, move freely into reticence. And in general, almost inevitably, we end up being rude to those who are very beautiful.

* * *

If it is true, as Claudel said, that “thought has a beat, like the brain and heart,” then fragmentary writing approaches like no other the pulsations of the mind. We do not think continuously; we are at the mercy of short circuits, interruptions. To think is a naturally discontinuous process, sealed by the discharges, quakes, lightning that often precede awareness, loosely speaking.

* * *

Reading, translation, music: different forms of procrastination. Days split open with hardly anything to show for it, dedicated to a paragraph or two; weeks without any significant advances. The quandary between writer’s block and literary impotence is still pending. I always associate it with a hall of mirrors, an “exterior” vision of myself, an attempt to understand how others see me. Thus, for example, the other night with K., having surpassed a certain alcoholic threshold, when I felt after being left alone as if I could see myself from the other side of the table. I had only to stretch out my hand to touch myself, but I preferred to remain my own incredulous spectator. A night to be forgotten, not so much because of the conversation—a rare occasion in these past few months, where I was able to lend form to themes that interest me, one of those chance “moments of friendship” Léautaud speaks of—but because I lingered too long before the public image of my own sterility.

* * *

Mirrors, preludes to my discomfort with physicality. I find myself too thin. Or too gangly. Unkempt. Unshaven. Hair. Glasses. But in the end, I know that none of this corresponds to reality; they are bewitched visions, the hallucinations of depression. Some afternoons, sex with V. redeems all of these insecurities. We hardly speak, but I dedicate my docile gratitude to her. I recognize her patience, her devotion, her passion as that of a 20-year-old Célimène who submits to the wonky, irascible professor – “sunken into black bile,” one might say.

There comes an age when our physique is first and foremost, part of a larger 180-degree turn of our attention toward the material nature of life itself. I recall years ago, reading Experience, the memoirs of Martin Amis, how all that rambling about his dental state seemed like a frivolous exercise to me. But now I understand that in Amis, the recurring theme of his teeth acts as a pretext to talk about physicality, about that material nature of the ego. It is almost always about something that runs parallel to sickness, to the wear and tear of the body.

* * *

It wasn’t the name that stopped me cold. It was that other line, just underneath: “Writer,” his card said. Just then, the one-armed bandit let out a roar and started spitting coins from its plastic mouth. The racket made all eyes turn to that corner of the bar. The “writer” murmured some excuse and slithered away, leaving me with his card. I put it away in my pocket, from where, now and again, it would reappear, reminding me of the ambiguous condition of that title. Was the “writer” a writer? Yes, he was, at least in the technical sense of the term: he had published various books. But I had a romantic notion of the writer that had little or nothing to do with that chubby, nervous, insecure figure, capable to dedicating hours to having that card made or to making it himself, and then handing it out at the slightest provocation. Writers—I thought—are people who lead a more fluid existence, who can ruminate their plotlines while strolling through a leather-bound library and who, above all, dominate the art of quieting the hubbub of details in order to privilege the essential. Today, I harbor a less elitist conceptualization. But all the same, I still find the title of “writer” on a business card unbearably vulgar.

* * *

I leaf through Havana Tile Designs, a beautiful little book edited by the mysterious Agile Rabbit Editions, and linger over the origin of the nostalgic enchantment that made it a near-bestseller among Cubans: in many of these floor tiles is ciphered our memory of certain colors, chromatic combinations that later fell into disuse or simply sank out of sight along with other ruins. These patterns were our Sezessionstil out there, surrounded by tropics. Reencountering them on the floors of the Barcelona Eixample came as a surprise a few years ago; far from Cuban decadence, but with flying colors, like the palm tree planted outside the home of the Indiano who has returned and publicly declares his longing. The memory of color is fragile, but intense. In a mosaic that caught my eye during a voyage to Lisbon, I recovered an old coffee set that had bounced around my grandparent’s home for years, chipped and falling into disuse; in Ravenna, once again I saw the colors of the earth I had played with as a child; in the uneven glow of the trencadis can also be found the kaleidoscope of all festive childhoods… The curse of the mosaic is compensated with this pure memory of an idealized palette reminiscent of an earlier time, some subtle and fragile colors and schemes that, at times, require long, vital intervals before they can reappear.

I remember now a note from the Ribeyro diaries: in Brussels, on a train, he sees a green and ochre propaganda sign go by that brings back the tiles from a hallway in his childhood, and the memory of that arabesque sets off a beautiful declaration of platonic faith: “In reality, we contain ourselves our entire lives. Everything is inscribed in our nature, whether as memory, as gesture, as defect, as opinion. Nothing is lost. Our most ancient and insignificant perceptions can be recovered by the employment of a suitable stimulant.” But the writer also notes that quotidian awareness puts up a certain resistance to that recovery, as if life were the natural enemy of memory. As if memory implied no longer living to the same degree that one recalls. In counterbalance to the bolero, recalling is not so much “going back to life,” but living to let live a little; the evocation is always one of time stolen from time; an arabesque trapped in symmetry, patches of color, fragments.

* * *

All too often literary existence is understood as the construction of an image of the author who escorts and “protects” the work: careful selections, emphases, reinventions. There is undeniable pleasure in the construction of that public figure, in the metamorphosis of that writer into “someone who writes.” All interviews, as a genre, form part of this process. But only the best show us the other side of that carriage: their virtue lies not so much in relating how things add up, but rather in denouncing those that have already been subtracted.

* * *

In fragmentary writing, the division between poetry and prose does not apply: the logical ties of the former find themselves weakened, threatened by rupture, by the latter’s blank spaces. These margins express the time required for our thoughts to congeal. All evidence of this mode of writing, which we conveniently refer to as “fragmentary,” are in reality a blank genre, a no man’s land, and its inhabitants deserve the description Julio Ramón Ribeyro dedicates to them: they are landless, “texts that do not fully adjust to any genre, given that they are neither prose poems, nor the pages of a personal diary, nor notes destined for later development… they lack their own literary terrain.”

* * *

How to determine the order of such a book and, above all, how to read it? One must forget the traditional, linear, logical process and operate in a transversal manner, based on internal resonances, taking into account that, as Baudelaire warns at the beginning of Le spleen de Paris, all serpent-texts are at the same time tête et queue, head and tail, cap i cua—according to the Catalonian phrase, transformed into a metaphor for the palindrome and popularized by the game of domino. Consider, Baudelaire tells the reader, the advantages of this combinatory system: “We can cut whatever we like—me, my reverie, you, the manuscript, and the reader, his reading; for I don’t tie the impatient reader up in the endless thread of a superfluous plot. Pull out one of the vertebrae, and the two halves of this tortuous fantasy will rejoin themselves painlessly. Chop it up into numerous fragments, and you’ll find that each one can live on its own.”

* * *

My friend Mallard the poliphyle has gone to Kiruna, Swedish Lapland, to help make a snow sculpture and contemplate the aurora borealis, both tasks of the utmost importance. Upon his return, he brings me a whistle made from a reindeer bone and the following phrase: “Curtains are the devil’s undergarments.”

It was coined by a rigorist monk who preached among the miners of Kiruna: an ascetic, leathery people subjected to the rigors of extreme nature. According to this sect and their preacher, the simple fact of needing curtains already implied the victory of sin: without them, nothing could exist that would allow one to dissemble.

Something similar takes place in Amsterdam, where Calvinism banned curtains: while strolling through the city, one can effortlessly see what is going on inside all of the houses. As for sin, it seems unlikely that this will put an end to it. Also Made in Holland was the famous TV program “Big Brother”: that spawn of diabolical transparency.

* * *

The small whirlpools that threaten a young soul. And the tenderness that always keeps us from being fully sincere. “Fiascos in bloom”, Beckett’s unbeatable definition.

* * *

That which we call “fragmentary writing” often stems from a non-dialectic appreciation of time. In Antiquity, there was a distinction between two kinds of time: that of Chronos, consecutive temporality, and that of Aion, which includes pauses, all that is infinitely sub-divisible, and that which can be fragmented. Thus, for example: down time, suffering, oblivion. Like being trapped in an interlude: the past pulls away toward that which we never know for certain whether or not it ever took place, while the future remains in suspense. Blanchot speaks of “the dispersion of a present that, even while being only passage does not pass, never fixes itself in a present, refers to no past and goes toward no future.” A writing that is often embroidered onto the time of such anticipation.

* * *

The enchanting simplicity and the profound wisdom of these verses describing the lover who leaves, in a rush, to catch the “Eleven o’clock train,” a song by Adoniran Barbosa in the voice of Gal Costa: Sou filho único / Tenho minha casa pra olhar…

* * *

As a last resort to stave off the rain, we drive a knife into the ground. A metonymical act, a sign of sympathetic magic: the invisible blood of the wounded Earth flows, triggering a drought in the heavens. This is a pact between contradictory meaning and primary elements, transposed in an act of violence that conjures the fury of Nature. But there are other meanings, which correlate on a different scale. Someone enabled me to see it this way: the buried blade rips into the grey canopy of clouds, dissolving it, draining the storm. It’s the gesture that counts; that wild faith in our determination to challenge nature, cleaving the blade in search of a magical lymph.

* * *

There can be no literarily effective memory without fragmentation, without blank spaces. Beckett explains this very nicely in his essay on Proust: “The man with a good memory does not remember anything because he does not forget anything. His memory is uniform, a creature of routine, at once a condition and function of his impeccable habit, an instrument of reference instead of an instrument of discovery. The paean of his memory: ‘I remember as well as I remember yesterday…’ is also its epitaph, and gives the precise expression of its value. He cannot remember yesterday any more than he can remember tomorrow.”

- This is an excerpt of La ruta natural, recently published in Vaso Roto (Madrid, 2015).

Ernesto Hernández Busto (La Habana, Cuba, 1968). Cuban poet, essayist, editor and translator resides in Barcelona. He is the author of Perfiles derechos. Fisonomías del escritor reaccionario (Península, Barcelona, 2004) and Inventario de saldos. Apuntes sobre literatura cubana (Colibrí, Madrid, 2005). He is a collaborator of El País.

Ernesto Hernández Busto (La Habana, Cuba, 1968). Cuban poet, essayist, editor and translator resides in Barcelona. He is the author of Perfiles derechos. Fisonomías del escritor reaccionario (Península, Barcelona, 2004) and Inventario de saldos. Apuntes sobre literatura cubana (Colibrí, Madrid, 2005). He is a collaborator of El País.

Así como Leopardi asocia lo poético a lo vago, a lo impreciso, al efecto de lo real pasado por el tamiz del recuerdo, Valéry nos advierte, en un célebre fragmento, que la sintaxis y las palabras de un poema han de ser “tan precisas como sea posible, pero el sentido debe permanecer impreciso, múltiple, jamás totalmente identificable con la función limitada de los términos”. Un poema es ese ensamblaje preciso que da lugar a lo impreciso, y de ahí proviene la radical extrañeza de la poesía, del estado de invención que nos regala.

* * *

Verano en Grossetto, adonde viajo para encontrarme con el poeta y psiquiatra Pedro Marqués de Armas. “Ciudad refugio” para escritores en la Maremma toscana, aburridísima. Un paisaje agreste, de un amarillo seco, y para colmo nos atrapa una ola de calor que rompe récords históricos. Imposible salir. De día apenas podemos quedarnos tendidos en la cama, leyendo y boqueando, cumpliendo una rutina de reptiles. De noche conversamos en la terraza.

Una de esas noches tórridas, Pedro me cuenta la historia de cómo conoció al poeta Ángel Escobar. No tomo notas, pero todo se queda dando vueltas en mi cabeza. Días después escribo esta versión de su relato, en una primera persona bastante libre:

“Fue en esos años que entré en el Hospital a hacer las prácticas, con la presunción añadida de cualquier psiquiatra recién graduado, uno más en las filas de los mecanicistas incurables del alma. Valdés Mier me convirtió en su protegido, y yo me sentía como si fuera el alumno preferido de Charcot, que ve la histeria brotar por todas partes –aquella mujer que entró una tarde en mi consulta, impresionante, con la leche que no paraba de salirle de los senos, una simple catatonia orgánica mal atendida.

Aunque ya habían pasado los peores años de las clasificaciones doctrinarias y las terapias reflexológicas, en la isla los psiquiatras teníamos que lidiar con todo tipo de trampas, las extrañas poses o fingimientos de unos pacientes cuyos perfiles no aparecían en los manuales. Síntomas que siempre me parecieron sutiles formas de respuesta psíquica a la muerte política, al fiasco de la personalidad libre, que encontraba otros cauces para sus inagotable dobleces. Algunos risibles, y otros dramáticos, como la cadena interminable de suicidios, muchos por irresponsabilidad médica, con los que tuve que lidiar desde el comienzo de las prácticas. No sé ni cómo aguanté aquello, pero así estuve, atendiendo casi indiferente a un batallón de mitómanos, inadaptados y suicidas, hasta que me tocó el Poeta, caso conmovedor de esquizofrenia real, de juego de voces atormentando aquella mente poderosa. Cuando fue aceptado en el hospital ya el Poeta era un guiñapo, pero lo cierto es que me ayudó a salir de aquel mundo de fríos dictámenes clínicos y tragedias insulares. Llegaba a la consulta con sus andares de marioneta, se sentaba en la silla y me recitaba sin parar sus odas esquizo. Y luego se iba, con los mismos andares de gente importante. Valdés Mier se reía de mí, de mi interés por el delirio de aquel hombre que un día era Rimbaud y otro Antonio Maceo, y me insistía en encerrarlo cuanto antes. Pero yo tenía una deuda con el Poeta y sus amigos, así que la pagaba recibiéndolo todas las semanas en el hospital de día y recetándole placebos que él guardaba con cuidado en una cajita de cartón, siempre abultando en el bolsillo de la camisa.

Hasta un día en que ya no pude hacer nada, y lo internaron, por fin, y se escapó de inmediato para poner de la manera menos grácil posible su cabeza debajo de un coche. ‘Debe ser un hombre importante’, me dijo la mujer que lo descubrió en plena calle cuando vino a alertarnos al Hospital. Pero era tarde, demasiado tarde, como todo en aquel país.”

* * *

Si es cierto que, como decía Claudel, “el pensamiento late, como el cerebro y el corazón”, entonces la escritura fragmentaria se acerca más que ninguna otra a las pulsaciones de la mente. No pensamos de manera continua; estamos a merced de los cortes, de la interrupción. Pensar es un proceso naturalmente discontinuo, signado por descargas, sacudidas, relámpagos, previos muchas veces a la conciencia en sentido lato.

* * *

Una de esas lluvias tropicales que no paran nunca. En la calle, la gente se afana con sus paraguas desflecados, un regimiento de corolas burlonas bajo un cielo de tafetán gris. Mirando por la ventana pienso en mi infancia sin pájaros, cuando un estornino era algo tan raro como esas joyas del tamaño de un huevo de paloma, que reposan tras cristales blindados en algunos museos, o engarzadas en el cetro de un antiguo reino, hoy república. De ahí mis excursiones, ya de adulto y con la inmejorable coartada de la paternidad, a todos los zoológicos posibles para dar cuerpo real a esas fantasías de infancia. Mi descubrimiento de un faisán en una aldea polaca. O la gorguera de un pato, comparable a una rara esmeralda.

* * *

No es difícil advertir la manera en que ciertos rasgos de las personas, un entramado de características físicas resuelto en una imagen clásica de la belleza, suscita confianza inmediata o, incluso, invita a acercarse. Sucede sobre todo con personas de un atractivo deslumbrante, persuasivo. Pero tal cercanía aparece como mera ilusión de una de las partes, pues a menudo esa belleza no es perceptible para quien vive, por así decirlo, dentro de ella. Luego, inevitablemente, la reticencia. La desconfianza propia de alguien diferente, que incluso cuando intenta ser amable no puede evitar hacernos sentir que nos trata con cierta indulgencia.

El impulso del observador al acercarse al objeto de su contemplación queda trunco, como un saludo en falso, y busca entonces cualquier motivo para disimularse: tras el atrevimiento viene siempre el reteso, una manera de compensar la diferencia. La belleza física, en ese sentido, siempre resulta injusta por desigual, ajena para los no escogidos, que de la devoción pasan pronto a la reticencia. Y por lo general, casi inevitablemente, uno acaba siendo grosero ante alguien muy hermoso.

* * *

Lectura, traducción, música, procrastinaciones varias. Días abiertos en canal sin mucho resultado, dedicados a dos párrafos, semanas sin mayor avance. Pende la pregunta por el bloqueo o la impotencia literaria. La asocio siempre con un salón de espejos, una visión “exterior” de mí mismo, un intento por entender cómo me ven los otros. Así, por ejemplo, la otra noche con K. cuando, rebasado cierto umbral alcohólico, al quedarme solo, sentí como si pudiera verme desde el otro lado de la mesa. Bastaba alargar la mano para tocarme, pero preferí seguir siendo un incrédulo espectador de mí mismo. Noche para olvidar, no tanto por la conversación –una de las pocas de estos últimos meses en las que pude dar forma a temas que me interesan, uno de esos raros “momentos de amistad” de los que hablaba Léautaud–, sino porque estuve demasiado rato frente a la imagen pública de mi propia esterilidad.

* * *

Los espejos, preludios de una incomodidad con lo físico. Me veo demasiado flaco. O demasiado desgarbado. Desarreglado. Sin afeitar. El pelo. Las gafas. Pero en el fondo sé que nada de eso corresponde a la realidad, son visiones embrujadas, las alucinaciones de la depresión. Algunas tardes, el sexo con V. redime todas esas inseguridades. Apenas hablamos, pero le dedico una gratitud mansa. Reconozco su paciencia, su entrega, su pasión de Celimena veinteañera entregada al profe filomático, atrabiliario –es decir, “hundido en la bilis negra”.

Hay una edad en la que nuestro físico pasa a un primer plano, parte de un vuelco mayor de nuestra atención sobre la materialidad de la vida toda. Recuerdo que hace años, mientras leía Experience, las memorias de Martin Amis, todas esas divagaciones sobre su dentadura me parecían un ejercicio de frivolidad. Pero ahora entiendo que en Amis el recurrente tema de sus dientes es un pretexto para hablar de lo físico, de esa materialidad del yo. Se trata casi siempre de algo que corre en paralelo a la enfermedad, al desgaste del cuerpo.

* * *

No me detuvo el nombre, sino la otra línea, justo abajo: “Escritor”, decía su tarjeta de presentación. Justo en ese momento la máquina tragaperras lanzó un rugido y empezó a escupir monedas en su boca de plástico. El estruendo hizo que todas las miradas se dirigieran hacia aquel rincón del bar. El “escritor” murmuró alguna excusa y se escurrió, dejándome con su tarjeta en la mano. La guardé en un bolsillo, y a cada rato reaparecía para recordarme la ambigua condición de aquel título. ¿Era escritor el “escritor”? Sí que lo era, al menos en el sentido técnico de la palabra: escribía, había publicado varios libros. Pero yo tenía una idea romántica del escritor que poco o nada correspondía a aquella figura regordeta, nerviosa, insegura, capaz de dedicar horas a encargar o hacerse esa tarjeta y repartirla a la primera provocación. Los escritores –pensé– son gente que lleva una existencia más fluida, que pueden rumiar sus tramas mientras pasean por una biblioteca encuadernada en piel, y que, sobre todo, dominan el arte de callar el bullicio de los detalles en beneficio de lo esencial. Hoy tengo una idea menos elitista. Pero igual, el título de “escritor” en una tarjeta de presentación me sigue resultando de una vulgaridad insoportable.

* * *

Hojeo Havana Tiles Designs, un hermoso librito editado por unas misteriosas Agile Rabbit Editions, y reparo en el origen del encanto nostálgico que casi lo convirtió en un bestseller entre cubanos: en muchas de esas losetas está cifrada nuestra memoria de ciertos colores, de unas combinaciones cromáticas que luego cayeron en desuso o se perdieron junto con otras ruinas. Esos patrones fueron nuestra Secessionsstil en mitad del trópico. Reencontrarlos en los pisos del Eixample barcelonés fue hace años una grata sorpresa; lejos de la decadencia cubana, airosos como la palmera plantada frente a la casa del indiano que ha vuelto y declara públicamente su añoranza. La memoria del color es frágil, pero intensa. En el mosaico entrevisto durante un viaje a Lisboa recobré un antiguo juego de café, que dio vueltas durante años por casa de mis abuelos, desportillado y caído en desuso; en Rávena volví a ver los colores de la tierra que toqué de niño; en la fulguración irregular del trencadís también está el caleidoscopio de toda infancia festiva… La maldición del mosaico se compensa con esa memoria pura de una paleta ideal que nos remite a un momento anterior, a unos colores y gamas sutiles y frágiles, que a veces requieren de largos intervalos vitales para reaparecer.

Recuerdo ahora un apunte de los diarios de Ribeyro: en Bruselas, desde un tren, ve pasar un anuncio de propaganda verde y ocre que le devuelve las losetas de un salón de su infancia, y el recuerdo de ese arabesco le provoca una hermosa declaración de fe platónica: “En realidad, nosotros contenemos toda nuestra vida. Todo se halla inscrito en nuestra naturaleza, sea como recuerdo, como gesto, como defecto, como opinión. Nada se ha perdido. Nuestras percepciones más antiguas e insignificantes pueden ser recuperadas por el empleo de un excitante adecuado”. Pero también nota el escritor que la conciencia cotidiana opone cierta resistencia a esta recuperación, como si la vida fuese enemiga natural de la memoria. Como si la memoria implicara dejar de vivir en la misma medida en la que se recuerda. A contrapelo del bolero, recordar no es tanto “volver a vivir”, sino dejar de vivir un poco; la evocación siempre es tiempo robado al tiempo, arabesco atrapado en la simetría, colores parcheados.

* * *

Demasiado a menudo se entiende la vida literaria como la construcción de una imagen de autor que escolta y “protege” la obra: selecciones cuidadosas, énfasis, reinvenciones. Hay un placer inobjetable en esa construcción de un personaje público, en esa metamorfosis del escritor en “alguien que escribe”. Todas las entrevistas, como género, forman parte de este proceso. Pero sólo las mejores nos muestran la otra cara de ese acarreo: su virtud radica menos en contar las cosas que se suman que en denunciar las otras que se restan.

* * *

En la escritura fragmentaria no procede la división entre poesía y prosa: los enlaces lógicos de ésta se ven resquebrajados, amenazados por los espacios en blanco característicos de aquella. Esas sangrías expresan el tiempo de coagulación de nuestros pensamientos. Todas las evidencias de ese modo de escritura que por conveniencia llamamos “fragmentos” son en realidad un género blanco, una zona de nadie, y sus habitantes merecen aquel calificativo que les dedica Ribeyro: apátridas, “textos que no se ajustan cabalmente a ningún género, pues no son poemas en prosa, ni páginas de un diario íntimo, ni apuntes destinados a un posterior desarrollo (…), carecen de un territorio literario propio”.

* * *

¿Cómo ordenar y, sobre todo, cómo leer un libro así? Es necesario olvidarse del proceso tradicional, lineal, lógico, y operar de manera transversal, desde las resonancias internas, teniendo en cuenta que, como advierte Baudelaire al comienzo de Le spleen de Paris, todo texto-serpiente es a la vez tête et queue, cabeza y cola, cap i cua, según la metáfora catalana del palíndromo – popularizada en el juego de dominó. Considerad, le dice Baudelaire al lector, las ventajas de ese sistema combinatorio: “podemos cortar donde queramos: yo, mis ensoñaciones; usted, el manuscrito; el lector, su lectura, porque yo no suspendo la voluntad remolona de éste al hilo interminable de una intriga superflua. Quitad cualquier vértebra y los dos trozos de esta tortuosa fantasía se acoplarán sin esfuerzo. Cortadla en múltiples fragmentos y comprobaréis que cada uno puede existir independientemente”.

* * *

Distancia inmediata ante algo tan banal como oírle contar a alguien la misma anécdota por segunda o tercera vez. No entiendo esa intolerancia, que a veces me provoca una mueca asociada, un tic que invade mi mejilla derecha en cuanto detecto la repetición. Por lo general, son anécdotas en primera persona; quien repite la historia debería recordarla mejor, puesto que está implicado en ella, casi siempre como protagonista. Pero hay aquí un rebajamiento cortesano de la memoria (y eso es tal vez lo que me repugna) a su condición de simple decorado, o escenario para el lucimiento. Qué uso tan pueril, superficial, de algo tan preciado. Una memoria sin rigor ni intimidad.

* * *

El amigo Mallard, poliphyle, se ha ido a Kiruna, en la Laponia sueca, para ayudar a hacer una escultura de nieve y contemplar una aurora boreal, tareas ambas de primerísima importancia. A su regreso me trae un silbato de hueso de reno y esta frase: “Las cortinas son los calzones del diablo”.

La decía un monje rigorista que predicó entre los mineros de Kiruna, gente ascética, curtida, sometida a los rigores de una naturaleza extrema. Para esta secta y su predicador el simple hecho de necesitar unas cortinas implicaba ya la victoria del pecado: si no había tal, tampoco debía existir nada que permitiera disimularlo.

Algo semejante ocurre en Amsterdam, donde el calvinismo desterró las cortinas: pasea uno por la ciudad y puede ver sin esfuerzo lo que sucede dentro de las casas. En cuanto al pecado, no parece que haya sido posible ponerle freno. En Holanda nació también el célebre programa de TV “Gran Hermano”, ese engendro de diabólica transparencia.

* * *

Los pequeños remolinos que amenazan un alma joven. Y la ternura, que siempre impide ser completamente sinceros. “Fiascos en flor”, insuperable definición de Beckett.

* * *

Eso que llamamos “escritura fragmentaria” procede muchas veces de una experiencia no dialéctica del tiempo. En la Antigüedad se distinguía entre dos tipos de tiempo: el de Cronos, temporalidad consecutiva, y el de Aión, que incluye las pausas, lo infinitamente subdividible, lo fragmentable. Así, por ejemplo, el tiempo de la espera, del sufrimiento, del olvido, como cuando uno está atrapado en un interludio: el pasado se aleja hacia lo que nunca sabemos bien si ocurrió y el futuro queda en suspenso. Blanchot habla de “la dispersión de un presente que no pasa, aún cuando es sólo pasaje; que no se convierte nunca en un presente, no se refiere a ningún pasado, no apunta a ningún futuro”. Una escritura bordada muchas veces sobre el tiempo de esa espera.

* * *

La encantadora simplicidad, y la profunda sabiduría, de esos versos del amante que parte, presuroso, a coger el “Tren de las once”, canción de Adoniran Barbosa en la voz de Gal Costa: Sou filho único/ Tenho minha casa pra olhar…

* * *

Para impedir que llueva, como último recurso, clavamos un cuchillo en la tierra. Acto metonímico, típico de la magia por contagio: la tierra herida, y su sangre invisible, para producir una sequía en los cielos. Alianza de sentidos y elementos trocados, un acto de violencia que conjura la furia de la Naturaleza. Pero también hay otros significados, en otra escala de correspondencias. Alguien me lo hace ver de esta manera: esa hoja enterrada rasga el toldo gris de los nubarrones, los disipa, drena la tormenta. Pero es el gesto lo que cuenta, la determinación en el acto de retar a lo natural, la fe salvaje que impulsa la faca en busca de la mágica linfa.

* * *

No hay memoria literariamente efectiva sin fragmento, sin espacios en blanco. Beckett lo explica muy bien en su ensayo sobre Proust: “El hombre con buena memoria no recuerda nada porque no olvida nada. Su memoria es uniforme, hija de la rutina, a la vez condición y función de su costumbre impecable, un instrumento de referencia en vez de uno de descubrimiento. El himno triunfal de su memoria –‘lo recuerdo como si fuera ayer…’– es también su epitafio y da la medida exacta de cuál es su valor. Es tan incapaz de acordarse del ayer como de recordar el mañana”.

- Textos tomados de La ruta natural, recientemente publicado bajo el sello de Vaso Roto (Madrid, 2015).

Ernesto Hernández Busto (La Habana, Cuba, 1968). Poeta, ensayista, editor y traductor cubano residente en Barcelona. Es autor de Perfiles derechos. Fisonomías del escritor reaccionario (Península, Barcelona, 2004) y de Inventario de saldos. Apuntes sobre literatura cubana (Colibrí, Madrid, 2005). Colabora en El País.

Ernesto Hernández Busto (La Habana, Cuba, 1968). Poeta, ensayista, editor y traductor cubano residente en Barcelona. Es autor de Perfiles derechos. Fisonomías del escritor reaccionario (Península, Barcelona, 2004) y de Inventario de saldos. Apuntes sobre literatura cubana (Colibrí, Madrid, 2005). Colabora en El País.

This article was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Great content, thank you Literal Magazine

Cheers!