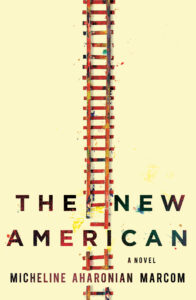

The New American

Micheline Aharonian Marcom

The Train

May 10, 2012

Here is a god more powerful than I am who, coming, will rule over me.

Dante Alighieri, La Vita Nuova

He is on the bus. The old Blue Bird school bus slowly climbs the steep and winding dirt road as it leaves the green misty valley of Todos Santos behind on its way to Huehuetenango two hours away, but he cannot see any of it through the windows in the darkness. In the seats near him, women hold their babies and toddlers and the old men hold their straw hats in their laps, bound chickens squawk and crik from their baskets overhead. The bus is filled with people of all ages and with their things tied up in big cloth sacks and cheap plastic bags. The engine is loud and cranks and the bus is crowded and cold and he wonders again how many days it will take to arrive and can I ever get it all back?

He had dressed carefully in the hour before dawn at his great-aunt’s house in dark blue jeans, a long-sleeved shirt, a tee shirt beneath that, new white tennis shoes with a red stripe sewn onto their sides, and his red baseball cap. He grabbed his nylon jacket at the last moment, and although it is the beginning of the warmer rainy season in the Highlands, the old bus is damp and unheated, and he is glad he is wearing it. He had already decided to bring the silver wristwatch his mother gave him three years ago when he graduated from high school and he turns his le wrist and looks at it: 5:20 am. He holds his small green backpack tightly on his lap.

Inside his old school pack he carries a plastic bottle of water, two lollipops he bought yesterday with his cousin’s children from a market stall, a paperback novel, a new journal (where he plans to keep a record of this journey), and a ballpoint pen. He carries an extra tee shirt, two changes of underwear, one pair of white athletic socks, a toothbrush, some paste, and a small piece of hard soap he had wrapped in a scrap of paper. He has four hundred dollars U.S. hidden beneath the insoles of his tennis shoes, two hundred in each shoe, all of what had remained in his bank account in California, and three hundred quetzales tucked into one of the pockets of his blue jeans. He carries another forty dollars in the other pocket along with a small color photograph of her folded between two ten-dollar bills. He thinks of the things he now carries on this bus and of what he left behind in Todos Santos: several pairs of blue jeans, tee shirts, the traditional red-striped pants and handwoven shirt his aunt purchased for him upon his arrival in town two-and-a-half weeks ago (without it, Emilio, you won’t look like one of our men, she’d said), a second pair of tennis shoes, three books he was assigned at university last term, his school ID, his old mobile telephone, his bank card. He thinks of his cash, his silver watch, the red cap and green pack and the book and journal and pen and how some things transit the earth easily and others do not. And he thinks how Aunt Lourdes will soon rise from her bed and discover his absence when she doesn’t find him in the main room on the sleeping pallet she borrowed from her eldest son, Anselmo. How she will walk next door and give Anselmo the news and his cousin will thereupon phone Berkeley and how his mother and sisters in Berkeley will begin to worry, as perhaps will she if she is apprised of it. Yet even so he will not call or contact his family or his girlfriend until he has made it a good distance from here: his mind is set on this course of action and he will follow it. And the winch he has imagined took residence inside him last February, ponderous and metallic, abutting his sternum, turns and pulls a wire from his bowels toward his stomach until his throat also cinches and he puts his hand into the jeans pocket with the quetzales and finds and fingers the white stone Antonia found for him on a beach in Northern California four months ago and he carries it back with him to the North.

He saw her standing atop the low seawall. Light brown hair pulled back into a ponytail, long legs in tight blue jeans, and a smile of hello in her blue eyes. She looked happy. He shouted out to her not to go into the ocean because the tide was unpredictable and she might drown. She replied that it was safe and warm and that she was a strong swimmer and she jumped off of the low seawall fully clothed into the water below and although they were at Muir Beach the sea looked different, calmer and darker blue, abutting the stones. He felt suddenly terrified and yelled out her name, but he didn’t jump into the water after her because of the paralysis the terror caused in his body and the tide rose and took her from him. She was saying something he couldn’t hear as she drifted farther and farther out, wave upon wave, to another place in the long distance, and he felt again his grief and rage and loneliness. He wanted to follow after her, he thought perhaps she might drown, but he remained where he was next to the seawall. He saw the back of her head like the head of a small sea lion far out in the dark blue water, near the light blue sky, as she drifted now onto the widest part of the ocean. Where has she gone? he thought.

*From THE NEW AMERICAN by Micheline Aharonian Marcom. Copyright © 2020 by Micheline Aharonian Marcom. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Micheline Aharonian Marcom has published six novels, including a trilogy of books about the Armenian genocide and its aftermath in the 20th century. Her first novel, Three Apples Fell From Heaven, was a New York Times Notable Book and Runner-Up for the PEN/Hemingway Award for First Fiction. Her second novel, The Daydreaming Boy, won the PEN/USA Award for Fiction. She is the founder and Creative Director of The New American Story Project [NASP], a digital oral history project focused on unaccompanied Central American minors who journeyed thousands of miles to reach the US.

Micheline Aharonian Marcom has published six novels, including a trilogy of books about the Armenian genocide and its aftermath in the 20th century. Her first novel, Three Apples Fell From Heaven, was a New York Times Notable Book and Runner-Up for the PEN/Hemingway Award for First Fiction. Her second novel, The Daydreaming Boy, won the PEN/USA Award for Fiction. She is the founder and Creative Director of The New American Story Project [NASP], a digital oral history project focused on unaccompanied Central American minors who journeyed thousands of miles to reach the US.

Posted: June 12, 2020 at 10:14 am